Be the Most Successful and Respected Tobacco Company in the World’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

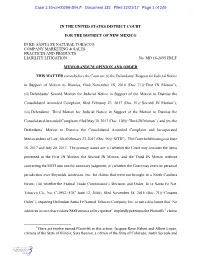

In the United States District Court for the District Of

Case 1:16-cv-00296-JB-LF Document 132 Filed 12/21/17 Page 1 of 249 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW MEXICO IN RE: SANTA FE NATURAL TOBACCO COMPANY MARKETING & SALES PRACTICES AND PRODUCTS LIABILITY LITIGATION No. MD 16-2695 JB/LF MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER THIS MATTER comes before the Court on: (i) the Defendants’ Request for Judicial Notice in Support of Motion to Dismiss, filed November 18, 2016 (Doc. 71)(“First JN Motion”); (ii) Defendants’ Second Motion for Judicial Notice in Support of the Motion to Dismiss the Consolidated Amended Complaint, filed February 23, 2017 (Doc. 91)(“Second JN Motion”); (iii) Defendants’ Third Motion for Judicial Notice in Support of the Motion to Dismiss the Consolidated Amended Complaint, filed May 30, 2017 (Doc. 109)(“Third JN Motion”); and (iv) the Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss the Consolidated Amended Complaint and Incorporated Memorandum of Law, filed February 23, 2017 (Doc. 90)(“MTD”). The Court held hearings on June 16, 2017 and July 20, 2017. The primary issues are: (i) whether the Court may consider the items presented in the First JN Motion, the Second JN Motion, and the Third JN Motion without converting the MTD into one for summary judgment; (ii) whether the Court may exercise personal jurisdiction over Reynolds American, Inc. for claims that were not brought in a North Carolina forum; (iii) whether the Federal Trade Commission’s Decision and Order, In re Santa Fe Nat. Tobacco Co., No. C-3952 (FTC June 12, 2000), filed November 18, 2016 (Doc. 71)(“Consent Order”), requiring Defendant Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company, Inc. -

Japan Tobacco to Take Over JTI (Malaysia)

Volume 32 Strictly For Internal Use Only April 2014 ASEAN: Updates on OTP - Bans and Regulations While we have been focusing on cigarettes, but what about Other Tobacco Products (OTP)? Some examples of OTP are smokeless tobacco, roll-your-own and cigarillos. In the Philippines, the law requires health warning on OTP, which is considered similar to cigarettes; there is an advertising ban on OTP in mass media while advertising at POS is permitted. In Cambodia, OTP is covered under the Sub-Decree No. 35 on the Measures to Ban Advertising of Tobacco Products in 2011. In Thailand, the TC law states any tobacco product coming from Nicotiana Tabaccum needs to be treated as same as cigarette, and OTP is included. For Vietnam, OTP is banned as stated in Article 9, Vietnam Tobacco Law which strictly prohibited advertising and promotion of tobacco products. In Lao PDR, OTP is covered by TC law as same as all type of cigarettes but there is no tax charge for OTP. With strong regulation on cigarettes, people may switch to OTP. According to regulations on OTP, countries consider them as harmful products that need to be banned. However, information on OTP is still lacking and it could result in escaping enforcement. The MAC Network is not limited to cigarettes only but includes OTP. Please share more information on OTP on SIS MAC Network Facebook for effective counteraction against all tobacco products. Malaysia: Japan Tobacco to take over JTI (Malaysia) April 1, (Free Malaysia Today) JT International (Malaysia), which makes Camel and Salem cigarettes, has received a takeover offer of RM808.4 million from Japan Tobacco to buy the remaining 39.63% or 103.549 million shares. -

South Carolina Tobacco Directory

South Carolina Tobacco Directory Updated: June 14, 2019 Office of the Attorney General South Carolina Tobacco Directory Alan Wilson Company Name Brand Name Original Certification Date Agreement type Status Cheyenne International LLC Decade 8/10/2005 NPM Compliant Aura 6/16/2014 NPM Compliant Cheyenne 8/10/2005 NPM Compliant Commonwealth Brands, Inc. USA Gold 8/10/2005 PM Compliant Crowns 3/16/2011 PM Compliant Rave 7/15/2009 PM Compliant Rave (RYO) 7/15/2009 PM Compliant Montclair 8/10/2005 PM Compliant Fortuna 9/15/2008 PM Compliant Sonoma 8/10/2005 PM Compliant Compania Tabacalera Internacional, S.A. Director 12/27/2017 NPM Compliant Dosal Tobacco Corporation 305 8/9/2010 NPM Compliant DTC 8/9/2010 NPM Compliant Firebird Manufacturing Cherokee 8/4/2010 NPM Compliant Palmetto 8/4/2010 NPM Compliant ITG Brands LLC Kool 8/12/2005 PM Compliant Winston 8/12/2005 PM Compliant Salem 8/12/2005 PM Compliant Maverick 8/11/2005 PM Compliant Japan Tobacco International U.S.A., Inc. Wave 8/10/2005 PM Compliant LD by L. Ducat 5/6/2016 PM Compliant Export A 8/10/2005 PM Compliant Kretek International Taj Mahal Bidis 10/18/2005 PM Compliant KT&G Corporation page: 0 of 1 Carnival 2/15/2012 NPM Compliant THIS 2/15/2018 NPM Compliant Timeless Time 2/15/2012 NPM Compliant Liggett Group Inc. Pyramid 8/9/2005 PM Compliant Liggett Select 8/9/2005 PM Compliant Eve 8/9/2005 PM Compliant Bronson 10/4/2011 PM Compliant Grand Prix 8/9/2005 PM Compliant Tourney 9/8/2005 PM Compliant Tourney Slims 8/9/2005 PM Compliant NASCO Products, LLC SF 1/5/2015 PM Compliant Native Trading Associates Mohawk 8/6/2013 NPM Compliant Native 6/14/2006 NPM Compliant Native (RYO) 12/10/2007 NPM Compliant Ohserase Manufacturing Signal 8/1/2011 NPM Compliant Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S Turkish Export (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant Danish Export (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant London Export (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant Amsterdam Shag (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant Stockholm Blend (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant Norwegian Shag (RYO) 8/15/2013 PM Compliant Philip Morris USA Inc. -

Brands MSA Manufacturers Dateadded 1839 Blue 100'S Box

Brands MSA Manufacturers DateAdded 1839 Blue 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Blue King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Blue 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Blue King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Green 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Green King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Non Filter King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Red 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Red King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 16oz Blue Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 16oz Full Flavor Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 16oz Menthol Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 6 oz Full Flavor Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 6oz Blue Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 6oz Menthol Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Silver 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Silver King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Blue 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Blue King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Menthol Green 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Menthol Green King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Menthol Silver 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Non Filter King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Red 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Red King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Silver 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 24/7 Gold 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Gold King Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Menthol 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Menthol Gold 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Menthol King Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Red 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Red King Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Silver Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 Amsterdam Shag 35g Pouch or 150g Tin Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S 7/1/2021 Bali Shag RYO gold or navy pouch or canister Top Tobacco L.P. -

INTERNATIONAL CIGARETTE PACKAGING STUDY Summary

INTERNATIONAL CIGARETTE PACKAGING STUDY Summary Technical Report June 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS RESEARCH TEAM ................................................................................................................... iv 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 2.0 STUDY PROTOCOL ........................................................................................................... 1 2.1 OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................ 1 2.2 SAMPLE AND RECRUITMENT ................................................................................. 2 3.0 STUDY CONTENT ............................................................................................................. 3 3.1 STUDY 1: HEALTH WARNING MESSAGES ............................................................... 3 3.2 STUDY 2: CIGARETTE PACKAGING ......................................................................... 4 4.0 MEASURES...................................................................................................................... 6 4.1 QUESTIONNAIRE DEVELOPMENT .......................................................................... 6 4.2 QUESTIONNAIRE CONTENT ................................................................................... 6 5.0 SAMPLE INFORMATION ................................................................................................... 9 REFERENCES ........................................................................................................................ -

“Mevius Mode 6 100'S” and “Mevius Mode 3 100'S”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Tokyo, April 21, 2015 Black Mevius Richer flavor through a lavish blend. Reduced smoke smell. “Mevius Mode 6 100’s” and “Mevius Mode 3 100’s” To be rolled out across Japan in early June, 2015 Japan Tobacco Inc. (JT) (TSE: 2914) has announced two new additions to the Mevius Mode series, which incorporates LSS* technology. “Mevius Mode 6 100’s” and “Mevius Mode 3 100’s” are to be rolled out across Japan in early June. A richer flavor through a lavish blend, and reduced smoke smell as well “Mevius Mode 6 100’s” and “Mevius Mode 3 100’s” The Mevius Mode Series products, which retain the smooth and clear flavor of Mevius and incorporate JT’s LSS technology, have been very well received by consumers. Now JT is launching “Mevius Mode 6 100’s” and “Mevius Mode 3 100’s”, in addition to the popular rich flavor “Mevius Mode One 100’s” launched in 2011. Thanks to a lavish blend, consumers can enjoy a richer flavor than that of the regular Mevius series. Employing the FSK size (approx.100 mm) instead of the FK one (approx. 85 mm) provides not just longer smoking experience, but also more satisfaction with each cigarette. In addition, the new products also incorporate LSS technology. The packages will feature the streamline motif of Mevius with vibrant blue and orange gradations on a black background. Furthermore, the sense of premium stylishness of the packages is enhanced by creating a special texture, which is achieved by ingenious use of gloss colors. -

Challenges to Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance

Challenges to Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a biological mechanism whereby a microorganism evolves over time to develop the ability to become resistant to antimicrobial therapies such as antibiotics. The drivers of and poten- tial solutions to AMR are complex, often spanning multiple sectors. The internationally recognized response to AMR advocates for a ‘One Health’ approach, which requires policies to be developed and implemented across human, animal, and environmental health. To date, misaligned economic incentives have slowed the development of novel antimicrobials and lim- ited efforts to reduce antimicrobial usage. However, the research which underpins the variety of policy options to tackle AMR is rapidly evolving across multiple disciplines such as human medicine, veterinary medicine, agricultural sciences, epidemiology, economics, sociology and psychology. By bringing together in one place the latest evidence and analysing the different facets of the complex problem of tackling AMR, this book offers an accessible summary for policy-makers, academics and students on the big questions around AMR policy. This title is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core. Michael anderson is a Research Officer in Health Policy at the Department of Health Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science, and a Medical Doctor undertaking General Practice specialty training. Michele cecchini is a Senior Health Economist, Health Division, in the Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. elias Mossialos is Brian Abel-Smith Professor of Health Policy, Head of the Department of Health Policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science, and Co-Director of the European Observatory on Health Systems. -

Sproule Et Al V. Santa Fe Natural Tobacco

Case 0:15-cv-62064-JAL Document 1 Entered on FLSD Docket 09/30/2015 Page 1 of 20 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA JUSTIN SPROULE, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated, No. Plaintiff, JURY TRIAL DEMANDED v. SANTA FE NATURAL TOBACCO COMPANY, INC., and REYNOLDS AMERICAN INC., Defendants. / CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Plaintiff, Justin Sproule, individually, and on behalf of all others similarly situated in the United States, by and through the undersigned counsel, files this Class Action Complaint, and alleges against Defendants, Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company, Inc. and Reynolds American Inc., as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. Defendants manufacture, market, and sell Natural American Spirit cigarettes (“American Spirits”). Defendants’ product labeling and advertising describes these cigarettes as “Natural,” “Additive Free,” “100% Additive Free,” “Organic,” and an “unadulterated tobacco product.”1 These terms are intended to suggest that American Spirits are healthier, safer, and present a lower risk of tobacco-related disease than other tobacco products. Defendants, however, have no competent or reliable scientific evidence to back their labeling and advertising claims. Defendants’ claims are patently deceptive, especially in today’s market, where these terms have a 1 https://www.sfntc.com/site/ourCompany/sfntc-story/ (last visited Aug. 28, 2015). Case 0:15-cv-62064-JAL Document 1 Entered on FLSD Docket 09/30/2015 Page 2 of 20 potent meaning for the health-and environmentally-conscious consumer. Moreover, as the FDA recently determined, American Spirits are in fact ‘adulterated.’ Using these deceptive terms, Defendants are able to successfully price American Spirits higher than other competitive cigarette brands. -

A TOBACCO-FREE SLOVENIA with the Help of Ngos

A TOBACCO-FREE SLOVENIA with the help of NGOs 1 Slovenian Coalition for Public Health, Environment and Tobacco Control-SCTC October 2019 A TOBACCO-FREE SLOVENIA with the help of NGOs Slovenian Coalition For Public Health, Environment and Tobacco Control October 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: And yet we’re smoking less ................................................................................................................... 3 A few facts Smoking and its consequences in Slovenia .................................................................................................................. 5 Toxins in cigarettes ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Electronic cigarettes ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Herbal cigarettes ........................................................................................................................................................... 8 Tobacco industry revenues ........................................................................................................................................... 9 WHO Framework Convention ..................................................................................................................................... 11 Slovenian legislation................................................................................................................................................... -

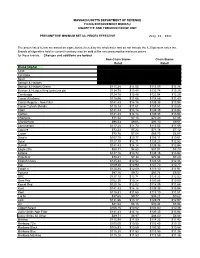

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

The New “Mevius Premium Menthol Option Red” Line to Be Launched Nationwide in Late August 2016

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 20, 2016 100% Natural Menthol × New Aroma-Changing Capsule The new “Mevius Premium Menthol Option Red” line to be launched nationwide in late August 2016 Tokyo, June 20, 2016 --- Japan Tobacco Inc. (JT) (TSE: 2914) has announced the nationwide launch of three new products from Mevius in late August: “Mevius Premium Menthol Option Red 8”, “Mevius Premium Menthol Option Red 5” and “Mevius Premium Menthol Option Red One 100’s”. With the celebration of its third anniversary in 2016, JT is strengthening the Mevius products and services, and accelerating the brand evolution to deliver the feel of “Ever Evolving, Ever Surprising.” to consumers. Following the upgrade of sixteen standard Mevius products and the launch of “Mevius Option Rich Plus” line, Mevius is releasing a completely new menthol line “Mevius Premium Menthol Option Red”. 100% Natural Menthol × New Aroma-Changing Capsule Launch of three new menthol products Since the name change from Mild Seven to Mevius, JT has been developing Mevius Premium Menthol products featuring its “100 percent Natural Menthol”1 proposition. “Mevius Premium Menthol” line offers consumers pure refreshing sensation delivered by 100 percent Natural Menthol, while “Mevius Premium Menthol Option” 2 and “Mevius Premium Menthol Option Yellow”3 lines allow consumers to enjoy flavoured menthol, by crushing the aroma-changing capsule. All of these products so far have been very well received by our consumers. To meet diversified needs of adult smokers, JT is launching three new “Mevius Premium Menthol Option Red” products with a new aroma-changing capsule developed by JT. Before crushing the capsule consumers will enjoy pure refreshing coolness through 100 percent Natural Menthol, which is unique to all Mevius Premium Menthol lines. -

6.-Market-Brief-Cigarette-HS-2402

RINGKASAN EKSEKUTIF Jepang berada di urutan ke-33 sebagai negara yang mengkonsumsi sigaret terbanyak di dunia. Berdasarkan Tobacco Atlas, setiap orang (usia di atas 15 tahun) mengkonsumsi 1.583,2 batang sigaret per tahun di tahun 2016, sementara orang Indonesia mengkonsumsi 1.675,5 batang sigaret per tahunnya. Selain itu, Jepang merupakan negara terbesar dan menduduki peringkat pertama sebagai negara pengimpor produk sigaret dunia (HS 2402) dengan pangsa 9,2% terhadap total impor sigaret dunia di tahun 2017. Tingginya konsumsi dan impor produk sigaret di Jepang tersebut menjadikan Jepang sebagai negara potensial tujuan ekspor yang dapat dikembangkan bagi produk sigaret Indonesia dengan kode HS 2402. Produk sigaret dengan kode HS 2402 yang banyak diimpor terkonsentrasi pada 2 (dua) jenis yaitu sigaret yang masuk ke dalam kode HS 240220 dan cerutu yang masuk ke dalam kode HS 240210. Penjualan sigaret di pasar domestik Jepang mencatat penurunan yang signifikan di tahun 2017 baik secara volume maupun nilai masing-masing sebesar - 12,9% dan -11,7%, namun demikian selama lima tahun terakhir, penjualan sigaret baik secara volume dan nilai masing-masing hanya turun sebesar -5,2% dan -4,0%. Di sisi lain, penjualan cerutu justru mengalami peningkatan baik secara volume dan nilai masing-masing sebesar 3,1% dan 2,6% serta memiliki pertumbuhan positif selama lima tahun terakhir masing-masing sebesar 3,4% dan 3,6%. Dalam lima tahun ke depan hingga tahun 2022, penjualan sigaret (HS 240220) di Jepang diprediksi akan tetap mengalami penurunan sebesar -9,3% (2017-2022 CAGR) sebaliknya penjualan cerutu (HS 240210) diprediksi tetap tumbuh positif selama lima tahun ke depan sebesar 1,3% (2017-2022 CAGR).