Contribution of Maryam Jameelah to Islamic Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egyptian Islamic and Secular Feminists in Their Own Context Assim Alkhawaja University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 2015 Complexity of Women's Liberation in the Era of Westernization: Egyptian Islamic and Secular Feminists in Their Own Context Assim Alkhawaja University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Alkhawaja, Assim, "Complexity of Women's Liberation in the Era of Westernization: Egyptian Islamic and Secular Feminists in Their Own Context" (2015). Doctoral Dissertations. 287. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/287 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco COMPLEXITY OF WOMEN‘S LIBERATION IN THE ERA OF WESTERNIZATION: EGYPTIAN ISLAMIC AND SECULAR FEMINISTS IN THEIR OWN CONTEXT A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education International & Multicultural Education Department In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education By Assim Alkhawaja San Francisco May 2015 THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO Dissertation Abstract Complexity Of Women‘s Liberation in the Era of Westernization: Egyptian Islamic And Secular Feminists In Their Own Context Informed by postcolonial/Islamic feminist theory, this qualitative study explores how Egyptian feminists navigate the political and social influence of the West. -

U.S. Muslim Charities and the War on Terror

U.S. Muslim Charities and the War on Terror A Decade in Review December 2011 Published: December 2011 by The Charity & Security Network (CSN) Front Cover Photo: Candice Bernd / ZCommunications (2009) Demonstrators outside a Dallas courtroom in October 2007during the Holy Land Foundation trial. Acknowledgements: Supported in part by a grant from the Open Society Foundation, Cordaid, the Nathan Cummings Foundation, Moriah Fund, Muslim Legal Fund of America, Proteus Fund and an Anonymous donor. We extend our thanks for your support. Written by Nathaniel J. Turner, Policy Associate, Charity & Security Network. Edited by Kay Guinane and Suraj K. Sazawal of the Charity & Security Network. Thanks to Mohamed Sabur of Muslim Advocates and Mazen Asbahi of the Muslim Public Affairs Council for reviewing the report, which benefitted from their suggestions. Any errors are solely those of CSN, not the reviewers. The Charity & Security Network is a network of humanitarian aid, peacebuilding and advocacy organizations seeking to eliminate unnecessary and counterproductive barriers to legitimate charitable work caused by current counterterrorism measures. Charity & Security Network 110 Maryland Avenue, Suite 108 Washington, D.C. 20002 Tel. (202) 481-6927 [email protected] www.charityandsecurity.org Table of Contents Executive Summary............................................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction......................................................................................................................................................... -

Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: a Critical Evaluation of Two Translations

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.8, No.2, 2017 Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: A Critical Evaluation of Two Translations Izzeddin M. I. Issa Dept. of English & Translation, Jadara University, PO box 733, Irbid, Jordan Abstract This study is devoted to discuss the renditions of the prophets' names in the Holy Quran due to the authority of the religious text where they reappear, the significance of the figures who carry them, the fact that they exist in many languages, and the fact that the Holy Quran addresses all mankind. The data are drawn from two translations of the Holy Quran by Ali (1964), and Al-Hilali and Khan (1993). It examines the renditions of the twenty five prophets' names with reference to translation strategies in this respect, showing that Ali confused the conveyance of six names whereas Al-Hilali and Khan confused the conveyance of four names. Discussion has been raised thereupon to present the correct rendition according to English dictionaries and encyclopedias in addition to versions of the Bible which add a historical perspective to the study. Keywords: Mistranslation, Prophets, Religious, Al-Hilali, Khan. 1. Introduction In Prophets’ names comprise a significant part of people's names which in turn constitutes a main subdivision of proper nouns which include in addition to people's names the names of countries, places, months, days, holidays etc. In terms of translation, many translators opt for transliterating proper names thinking that transliteration is a straightforward process depending on an idea deeply rooted in many people's minds that proper nouns are never translated or that the translation of proper names is as Vermes (2003:17) states "a simple automatic process of transference from one language to another." However, in the real world the issue is different viz. -

Tafsīr Surah Al-Kafirun

Tafsīr Surah al-Kafirun By Haider Hobbollah Transcribed and translated by Syed Ali Imran (Canada) Names, Reasons of Revelation The chapter has been referred to in three ways in Islamic works: 1. Surah al-Kāfirūn 2. Surah al-Juḥd – since Juḥd means rejection, this name was probably given due to the rejection that appears in the later verses 3. Surah al-Muqashqisha – some have called both this and Surah Ikhlās together as al-Muqashqishatān. Qashqasha means to sweep away and abandon something, and the chapter is given this name because of the rejection (barā’ah) mentioned in the verses. A group of disbelievers in Makkah, including al-Ḥārith b. Qays al-Sahmī, al-‘Āṣ b. Wā’il, al-Walīd b. Mughīrah, Umayyah b. Khalaf and others, came to the Prophet (p) and said to him, why do you not worship what we worship, and we will worship what you worship for a time period, after which we will see whose god and worship is better, who sees the results of their worship soon after. If your god and worship are better then that will be a moment of pride for the Quraysh and we will take a share of it, but if you (p) find that our gods and worship are better then you shall take a share of it. As per historical reports, the Prophet (p) rejected their offer. This chapter was revealed and the Prophet (p) left the Masjid al-Ḥarām and recited it in front of the people. This is the popular report describing the reasons for the chapter’s revelation, both in Sunnī and Shī’ī texts, the latter works including traditions from the Ahl al-Bayt (a) as well. -

Presidential Files; Folder: 7/19/77; Container 32

7/19/77 Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 7/19/77; Container 32 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf WITHDRAWAL SHEET (PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARIES) FORM OF CORRESPONDENTS OR TITLE DATE RESTRICTION DOCUMENT memo From Bob Thomson to The President (2 pp.) re: 7/15/77 c Nomination of Don Tucker to the CAB/ enclosed in Hutcheson to Moore 7/19/77 -. " - .• FILE LOCATION Carter Presidential Papers- Staff Offices,. Office of the Staff Sec.- Presidential Handwriting File 7/19/77 Box ~ RESTRICTION CODES (A) Closed by Executive Order 12356'governing access to national security information. (B) Closed by statute or by the agency which originated the document. (C) Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in the donor's deed of gift. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION. NA FORM 1429 (6-85) ~l'IIE PRESIDENT'S SCHEDULE Tuesday ~ July 19, 1977 . 7:15 Dr. Zbignicw Brzezinski - Oval Office. 7:45 Mr. Frank Moore - The Oval Office. 8:00 Breakfast with Senate Group. (Mr. Frank Moore). ( 6 0 min.) The Roosevelt Room. 9:15 Senator Daniel Moynihan. (Mr. Frank Moore). (15 min.) The Oval Office. 10:00 Hr. Jody Pmvell The Oval Office. 10:30 Arrival Ceremony for.His Excellency The Prime ' Minister of Israel and Mri. Menahe~ Begin. The South Grounds. 11:00 Meeting with Prime Minist~r Menahem Begin. (90 min.) (Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski) - Oval Office and Cabinet Room. 1:30 Vice President lval ter F. Mondale, Admiral (20 min.) Stansfield Turner, a~d Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski. The Oval Office. -

Best Copy Available J "I \ I

Document Symbol: A/2437 Best copy available j "i \ I UNiTED NA1'IONS REPORT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL TO THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY Covering the period from 16 July 1952 to 15 July 1953 GENERAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL RECORDS: EIGHTH SESSION SUPPLEMENT No. 2 (A/2437) NEW YORK, 1953 UNITED NATIONS REPORT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL TO THE GENERAL ASSEl\fBLY Covering the period from 16 July 1952 to 15 July 1953 GENERAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL RECORDS: EIGHTH SESSION SUPPLEMENT No. 2 (A/2437) New York, 1953 NOTE All United Nations documents are designated by symbols, i.e., capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United :0T ations document. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION V PART I Questions considered by the Security Council under its responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security C!z(l.pter 1. THE INDIA-PAKISTAN QUESTION 1 PART n Other matters considered by the Security Council 2. ADMISSION OF NEW MEMBERS 12 3. ApPOINTMENT OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL .. 24 PART III The Military Staff Committee 4. \VORK OF THE MILITARY STAFF COMMITTEE. ........................... 26 PART IV Matters brought to the attention of the Security Council but not discussed in the COUlwiI 5. COMMUNICATIONS RELATING TO THE PALESTINE QUESTION. ............... 27 6. CO:\IMUNICATIONS RELATING TO THE KOREAN QUESTION . .. 28 7. COMPLAINT OF FAILURE BY THE IRANIAN GOVERNMENT TO COMPLY WITH PROVISIONAL MEASURES INDICATED BY THE INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE IN THE ANGLO-IRANIAN OIL COMPANY CASE 28 8. REPORT ON THE TRUST TERRITORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS. ............ 28 9. A REPORT OF THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE BRITISH-UNITED STATES ZONE OF THE FREE TERRITORY OF TRIESTE 29 10. -

Presidents of the United Nations General Assembly

Presidents of the United Nations General Assembly Sixty -ninth 2014 Mr. Sam Kahamba Kutesa (Pres i- Uganda dent-elect) Sixty -eighth 2013 Mr. John W. Ashe Antigua and Barbuda Sixty -seventh 2012 Mr. Vuk Jeremić Serbia Sixty -sixth 2011 Mr. Nassir Abdulaziz Al -Nasser Qatar Sixty -fifth 2010 Mr. Joseph Deiss Switzerland Sixty -fourth 2009 Dr. Ali Abdussalam Treki Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Tenth emergency special (resumed) 2009 Father Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann Nicaragua Sixty -third 2008 Father Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann Nicaragua Sixty -second 2007 Dr. Srgjan Kerim The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia Tenth emergency special (resumed twice) 2006 Sheikha Haya Rashed Al Khalifa Bahrain Sixty -first 2006 Sheikha Haya Rashed Al Khalifa Bahrain Sixtieth 2005 Mr. Jan Eliasson Sweden Twenty -eighth special 2005 Mr. Jean Ping Gabon Fifty -ninth 2004 Mr. Jean Ping Gabon Tenth emergency special (resumed) 2004 Mr. Julian Robert Hunte Saint Lucia (resumed twice) 2003 Mr. Julian Robert Hunte Saint Lucia Fifty -eighth 2003 Mr. Julian Robert Hunte Saint Lucia Fifty -seventh 2002 Mr. Jan Kavan Czech Republic Twenty -seventh special 2002 Mr. Han Seung -soo Republic of Korea Tenth emergency special (resumed twice) 2002 Mr. Han Seung -soo Republic of Korea (resumed) 2001 Mr. Han Seung -soo Republic of Korea Fifty -sixth 2001 Mr. Han Seung -soo Republic of Korea Twenty -sixth special 2001 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Twenty -fifth special 2001 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Tenth emergency special (resumed) 2000 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Fifty -fifth 2000 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Twenty -fourth special 2000 Mr. Theo -Ben Gurirab Namibia Twenty -third special 2000 Mr. -

The Muslim Manifesto (1990)

THE MUSLIM MANIFESTO (1990) - www.kalimsiddiqui.com Publisher’s introduction The Muslim Manifesto was published by the Muslim Institute at a conference on ‘The Future of Muslims in Britain’ held by in Logan Hall, the Institute of Education, London, on 14 July 1990. It was the result of several months of consultations with leading Muslim community figures in Britain, led by Dr. Kalim Siddiqui, Director of the Muslim Institute. It aimed to provide out “a common text THE defining the Muslim situation in Britain”, and proposed the creation of a range of community institutions under a ‘Council of British MUSLIM Muslims’. It was this proposal that led to the establishment of the Muslim Parliament of Great Britain, inaugurated in January 1992. MANIFESTO The writing of the Muslim Manifesto emerged from the Satanic Verses controversy, in which Dr. Siddiqui became a spokesman for the British Muslims’ anger and frustration, and a defender of their - a strategy for survival position in the face of attacks from the literary and political establishments, and the mass media. From the outset of the controversy, while others were focused on the book and its author, Dr Siddiqui understood the broader implications for the position of Muslims in Britain, and sought to channel Muslim energies to constructive programs for the future benefit of the community. The Muslim Parliament was still in its early stages at the time of Dr Siddiqui’s death in 1996, and unfortunately did not long survive him. For more information on it, see http://kalimsiddiqui.com/ muslim-parliament. www.kalimsiddiqui.com January 2016. -

Bibliography of Works Consulted

98 Muslim Worldviews and the Bible: (Part III: Women, Purity, Worship and Ethics) One should bring honor to Christ, by honest means, x One should, by almost any means, promote and protect the even if one appears foolish to others or displeases honor of one’s family and of Islam. one’s family. One should seek guidance from God through the x One should seek guidance by learning the Islamic law and Bible, prayer, and the Holy Spirit. following it. Popular: One can seek divine guidance from saints and others who have a gift for this service. Believers should feel ashamed if they dishonor or displease | The Muslim generally feels ashamed when others reproach God. However, if they are following Christ, then they him or his family or a member of his family. Avoidance expect reproach and persecution from worldly people. of shame is perhaps the strongest factor affecting social behavior. The family should keep its womenfolk from shaming them by committing a sexual indiscretion; shame can be alleviated by strictly punishing the offending woman. One should practice hospitality even to strangers. ~ The practice of hospitality and generosity bring honor to the family; its lack brings dishonor. One should work and not be idle. Work with the X A man should not work if it is not necessary. Manual labour hands is honorable. is not honorable. IJFM Bibliography of Works Consulted Abdul-Khaliq, Abdur-Rahmaan Brown, Rick Cragg, Kenneth 1986 The General Prescripts of Belief 2000 The Son of God: Understanding 1988 The Pen and the Faith: Eight in the Qu’ran and Sunnah. -

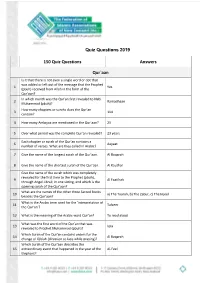

Quiz Questions 2019

Quiz Questions 2019 150 Quiz Questions Answers Qur`aan Is it that there is not even a single word or dot that was added or left out of the message that the Prophet 1 Yes (pbuh) received from Allah in the form of the Qur’aan? In which month was the Qur’an first revealed to Nabi 2 Ramadhaan Muhammad (pbuh)? How many chapters or surahs does the Qur’an 3 114 contain? 4 How many Ambiyaa are mentioned in the Qur’aan? 25 5 Over what period was the complete Qur’an revealed? 23 years Each chapter or surah of the Qur’an contains a 6 Aayaat number of verses. What are they called in Arabic? 7 Give the name of the longest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Baqarah 8 Give the name of the shortest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Kauthar Give the name of the surah which was completely revealed for the first time to the Prophet (pbuh), 9 Al Faatihah through Angel Jibrail, in one sitting, and which is the opening surah of the Qur’aan? What are the names of the other three Sacred Books 10 a) The Taurah, b) The Zabur, c) The Injeel besides the Qur’aan? What is the Arabic term used for the ‘interpretation of 11 Tafseer the Qur’an’? 12 What is the meaning of the Arabic word Qur’an? To read aloud What was the first word of the Qur’an that was 13 Iqra revealed to Prophet Muhammad (pbuh)? Which Surah of the Qur’an contains orders for the 14 Al Baqarah change of Qiblah (direction to face while praying)? Which Surah of the Qur’aan describes the 15 extraordinary event that happened in the year of the Al-Feel Elephant? 16 Which surah of the Qur’aan is named after a woman? Maryam -

ISLA Journal of International & Comparative

ILSA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL & COMPARATIVE LAW NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY SHEPARD BROAD LAW CENTER INTERNATIONAL PRACTITIONER'S NOTEBOOK EDITION Volume 12 Spring 2006 Number 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Litigating the Holocaust in U.S. Courts: Perspectives on the Process And its Aftermath International Law Weekend Panel on Litigating the Holocaust in U.S. Courts .................... Monica Dugot 389 Advancing the Effectiveness of International Law: Is U.N. Reform Necessary? Enhancing Accountability at the International Level: The Tension Between International Organization and Member State Responsibility and the Underlying Issues at Stake ................. Ralph Wilde 395 The Hague Convention on Choice-of-Court Agreements: Strengthening Compliance with International Commercial Agreements and Ex-Ante Dispute Resolution Clauses? After the Hague: Some Thoughts on the Impact of Canadian Law of the Convention on Choice of Court Agreements ......... H. Scott Fairley and John Archibald 417 The 2005 Hague Convention on Choice of Court Clauses ................................ Andrea Schulz 433 Applying Human Rights Law and Humanitarian Law in the Extraterritorial War Against Terrorism: Too Little, Too Much, or Just Right? Application of Human Rights Treaties Extraterritorially to Detention of Combatants and Security Internees: Fuzzy Thinking All Around? .. Michael Dennis 459 Filling the Void: Providing a Framework for the Legal Regulation of the Military Component of the War on Terror Through Application of Basic Principles of the Law of Armed Conflict ...... Geoffrey Corn 481 International Law and the Humanities International Law and the Humanities: Does Love of Literature Promote International Law? ... Daniel Kornstein 491 International Arbitrators: Civil Servants? Sub Rosa Advocates? Men of Affairs? The Role of International Arbitrators ............... Susan Franck 499 What is War? What is War? Terrorism as War after 9/11 .......... -

Tafseer Surah Al-Fil Notes on Nouman Ali Khan’S Concise Commentary of the Quran

(اﻟﻔﯿﻞ) Tafseer Surah al-Fil Notes on Nouman Ali Khan’s Concise Commentary of the Quran By Rameez Abid Introduction ● This surah is in reference to the story of Abraha, who was a Christian military leader and part of the Roman empire, and it took place before the birth of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh). He built a huge church and wanted the Arabs to venerate it instead of the Ka’ba. He also wanted to do this for financial reasons because due to the Ka’ba, Mecca was a center for business and he wanted to shift the financial attention to his own region in Yemen ○ Some Arabs went to his new church and defecated in it to insult him for trying to take attention away from the Ka’ba. Abraha was furious and decided to take an army of 60,000, which would consist of elephants as well, to Mecca to destroy the Ka’ba in vengeance ■ However, when he got close to the Ka’ba with his army, Allah destroyed them by sending birds who pelted them with stones ○ Some suggest this was the year in which the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) was born ● Some of the companions viewed this surah and the one after it (Surah al-Quraysh) as one surah. They would not put Basmallah between them for that reason ○ They both need to be understood together because they complement each other and are connected ■ This surah discusses the security of Mecca and Surah al-Quraysh discusses its prosperity. For any society to prosper, it needs both of these things ○ We need to understand that the safety and prosperity of Mecca was due to the supplication of Ibrahim (pbuh), which he made when he was building the Ka’ba with his son Ismaeel (pbuh) ■ He had asked Allah to make Mecca safe and fill it with all kinds of fruit because it was a barren desert without life.