Incomprehensible. How Could the Prime Minister of a Self-Governing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air Service Newsletters 1918

PROPERTY OF 0.S.'100 ,.,'. ."~''';~ , t"',1.. :1.,•... ,"..A; A/' l .' Of'I:.J~EOF AIR FORCE HISTOR} r-:; .rfiL -:y.t / 1'rOll1 tho if£' .~ lfli"''';;.ewareDeJ;>artment nut:>.orizes the following: Irrespecti ve o f status in the draft, t>e ~Ur Service has been re- opened ro ..' i::lduc tion 0 f :,leC;:18.ni08and. of cand.idat es fo r comcu.ss i.one as " pi lots, bomber-a, observer s an d b8.11ool1ists, z,fter havi ng been. closed EW..oSptfor,a few isolated cLas se s for tile ;?c\st s1::: month s , The fast moving overseas of 2.11' s quad ...~ons, ~?lanes, motors and mate:;'1ial for Junerio8.n airclr<:nnes, fields, and asscl.lb1y :;;>151ts in :i<'rai'lce and E'l1g1and, together with the cOlW,?letion here of 29 flyu-€: :fields, 1200 de Ha'iilar.d 1::>lanes,6000 Mbe:dy motors, 't.l0 parts for ti"le first heavy l1igl:.t bombers, 6pOO trainii'lG planes and 12,500 tro.ini:1C e11c;i11oS,ha s led to the necessity of increasi:'Jg bOt}l tlle coranuas Loned 8:...10. tJJ8 enlis ted ~:~ersonne'l, in 0 rder to m~1nte.in full streng'th in ells count ry and continue t~le nec es sary flow . overseas. As e. r esu l t tl::,e Air Se::,'vice, alone, is now lia Lf as large agD,in as . the whole-,~i1e:dc8.ll )-l":';),y was at ti:e out'bre8Jc of 'Vlar. Ci viJ.iaYts have no t been gi ven an o))orttlni t'~T to ql.lalif;y as :9ilots since last L:ar'cl1. -

Penttinen, Iver O

Penttinen, Iver O. This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on October 31, 2018. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard First revision by Patrizia Nava, CA. 2018-10-18. Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Penttinen, Iver O. Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Sketch ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Image -

Our Canadian Aerospace Industry: Towards a Second Century of History-Making

Our Canadian Aerospace Industry: Towards a Second Century of History-making Presentation by Robert E. Brown President and Chief Executive Officer CAE Inc. Before the AIAC 47th Annual General Meeting and Conference Wednesday, September 17, 2008 Page 1 Good morning, Ladies and Gentlemen. It is a pleasure for me to be here today and acknowledge the presence of so many friends and business partners. Next year, Canada will mark the 100th anniversary of the first airplane flight over our land. In February 1909, a pioneer by the name of J.A.D. McCurdy took to the sky in a frail-looking biplane called the Silver Dart. Young McCurdy and Canada’s tiny aviation community never looked back, and as a result, their daring achievement led to the development of a whole new industry — our own aerospace industry. How did a country with a population of 7 million in the early 20th century become the fourth nation in the world in the field of aerospace? How did Montreal become the only place in the world where you can build an entire aircraft? How did we manage to attract, develop and hang on to global leaders like Bell Helicopter Textron, Pratt & Whitney Canada and Bombardier? And, closer to my own heart, how did an enterprise like CAE become a world leader in civil simulation, with more than 70% of the market? How can a country as small as Canada, have such a glorious jewel in its crown? To find the answers to these questions, one must go back in time. Shortly after McCurdy’s groundbreaking flight, World War 1 saw Canada’s aviation industry take off. -

(RE 13728) an RFC Recruit's Reaction to Spinning Is Tested in a Re

This J N4 of RAF Canada carried the first ainnail in Canada. (R E 13728) An RFC recruit's reaction to spinning is tested in a revolving chair. (RE 19297-4) Artillery co-operation instruction RFC Canada scheme. The diagrams on the blackboard illustrate techniQues of rang.ing. (RE 64-507) Brig.-Gen. Cuthbert Hoare (centre) with his Air Staff. On the right is Lt-Col. A.K. Tylee of Lennox ville, Que., responsible for general supervision of training. Tylee was briefly acting commander of RAF Canada in 1919 before being appointed Air Officer Commanding the short-lived postwar CAF in 1920. (RE 64-524) Instruction in the intricacies of the magneto and engine ignition was given on wingless (and sometimes tailless) machines known as 'penguins.' (AH 518) An RFC Canada barrack room (RE 19061-3) Camp Borden was the first of the flying training wings to become fully organized. Hangars from those days still stand, at least one of them being designated a 'heritage building.' (RE 19070-13) JN4 trainers of RFC Canada, at one of the Texas fields in the winter of I 917-18 (R E 20607-3) 'Not a good landing!' A JN4 entangled in Oshawa's telephone system, 22 April 1918 (RE 64-3217) Members of HQ staff, RAF Canada, at the University of Toronto, which housed the School of Military Aeronautics. (RE 64-523) RFC cadets on their way from Toronto to Texas in October 1917. Canadian winters, it was believed, would prevent or drastically reduce flying training. (RE 20947) JN4s on skis devised by Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd, probably in February 1918. -

William Faulknerâ•Žs Flight Training in Canada

Studies in English Volume 6 Article 8 1965 William Faulkner’s Flight Training in Canada A. Wigfall Green University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Green, A. Wigfall (1965) "William Faulkner’s Flight Training in Canada," Studies in English: Vol. 6 , Article 8. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng/vol6/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in English by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Green: William Faulkner’s Flight Training in Canada WILLIAM FAULKNER'S FLIGHT TRAINING IN CANADA by A. Wigfall Green “I created a cosmos of my own,” William Faulkner said to Jean Stein in New York in midwinter just after 1956 had emerged. “I like to think of the world I created as being a kind of key stone in the Universe.” He was speaking, obviously, of the small world of his fiction which reflected in miniature the great world of fact. “The reason I don’t like interviews,” he said, turning from his novels to himself, “is that I seem to react violently to personal questions. If the questions are about the work, I try to answer diem. When they are about me, I may answer or I may not, but even if I do, if the same question is asked tomorrow, the answer may be different.”1 And he might have said more: that he as mythmaker enjoyed deluding the public concerning his entire background. -

Notes to Pages 485-92 709

Notes to Pages 485-92 709 13 Jones, War in the Air, 1v. 287-8. app. XVII. 453-{i 14 Ibid., 284-5 15 Canadian Bank or Commerce, Leners from the From: Being a Record of the Part Played by Officers o.fthe Bank in the Great War. 1914-1919, C.L. Foster and W.S. Duthie, eds. (Toronto I 1920-1 )). 1, 256 16 'Fl ugzeugverluste an der Westfront Miirz bis September 1918,' in Deutschland, Oberkommandos des Heeres, Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918 . Band x iv Beilagen: Die Kriegfiihrung an der Wesifro111 im Jahre 1918 (Berlin 1944), Beilage 40 17 Ibid.; 84 Squadron air combat repons, 17 March 1918, Air 1/1227/204/5/2634/84: 84 Squadron operational record, 17 March 1918, Air 1/1795/204/155/2 18 K. Bodenschatz. ' Das Jagdgeschwader Frhr.v.Richthofen Nr I.' quoted in G.P. Neumann, ed .• In der left u11besieg1 (MUnchen 1923), 227. DHist SO R 1 196. Set 72 19 [E.) Ludendorff, My War Memories, 1914-1918 (London nd), 11, 589, 596; Edmonds, Military Operations: France and Belgium, 1918. 1, 109, 154-5; Jones, War in the Air, IV, 268 20 Jones, War in the Air, 1v. 268: Edmonds. Military Operatio11s: France and Belgium, 1918, I, 109, 152-4 21 Jones, War in 1he Air, 1v, app. xvi, table 'A': France, Ministere de la Guerre. Etat-Major de l'Armee, Service Historique, Les Armeesfrant,aises da11s la Kra11de Guerre (Paris 193 1), Tome v1. 1, 168-9n 22 v Brigade work summary, 21 March 1918, Air 1/838/204/5/285; Ludendortf, War Memories, 11 . -

Cold War Fighters Canadian Aircraft Procurement, 1945-54 Randall Wakelam

Cold War Fighters Canadian Aircraft Procurement, 1945-54 Randall Wakelam Sample Material © 2011 UBC Press Click here to buy this book: www.ubcpress.ca Contents List of Illustrations / vi Preface / vii Abbreviations and Acronyms / xiii 1 An Air-Minded Middle Power / 1 2 Planning for Peace / 19 3 International and Industrial Alliances / 34 4 Caught Flat-Footed / 44 5 Facing the Threat in Earnest / 63 6 And So to War / 81 7 Juggling Numbers / 105 8 Putting Rubber on the Ramp / 118 9 Growing Needs, Growing Concerns / 129 10 Fact and Fancy / 142 Appendix A: Royal Canadian Air Force Headquarters Organization Chart, c. 1947 / 148 Appendix B: Department of Defence Production Aircraft Delivery Statistics, 1951-54 / 149 Notes / 154 Bibliography / 175 Index / 180 Sample Material © 2011 UBC Press Click here to buy this book: www.ubcpress.ca Illustrations Figures 1 Louis St-Laurent and Lester Pearson at an early UN meeting / 93 2 North Star / 94 3 Avro Jetliner / 95 4 De Havilland Vampire / 95 5 Mustang / 96 6 Sabre wing centre section / 96 7 Sabre production line / 98 8 Sabre rollout ceremony / 98 9 First run of Chinook engine / 99 10 Sir Roy Dobson / 100 11 Accepting the first Canuck / 101 12 Canuck wing issues / 101 13 CF-100 assembly line / 102 14 CF-100 outside the factory / 103 15 German F-86s / 103 16 A Belgian CF-100 / 104 Tables 2.1 RCAF Plan B fighter units / 32 2.2 RCAF Plan B fighter requirements / 32 4.1 RCAF Plan E fighter units / 55 4.2 Fighter operational requirements / 59 B.1 Production figures for 1951 / 150 B.2 Production figures for 1952 / 151 B.3 Production figures for 1953 / 152 B.4 Production figures for 1954 / 153 Sample Material © 2011 UBC Press Click here to buy this book: www.ubcpress.ca Preface Before I turn to the history of Cold War fighters, it is appropriate to present a number of factors that have helped me frame the story and to discuss one or two matters of terminology. -

Aircraft Designations and Popular Names

Chapter 1 Aircraft Designations and Popular Names Background on the Evolution of Aircraft Designations Aircraft model designation history is very complex. To fully understand the designations, it is important to know the factors that played a role in developing the different missions that aircraft have been called upon to perform. Technological changes affecting aircraft capabilities have resulted in corresponding changes in the operational capabilities and techniques employed by the aircraft. Prior to WWI, the Navy tried various schemes for designating aircraft. In the early period of naval aviation a system was developed to designate an aircraft’s mission. Different aircraft class designations evolved for the various types of missions performed by naval aircraft. This became known as the Aircraft Class Designation System. Numerous changes have been made to this system since the inception of naval aviation in 1911. While reading this section, various references will be made to the Aircraft Class Designation System, Designation of Aircraft, Model Designation of Naval Aircraft, Aircraft Designation System, and Model Designation of Military Aircraft. All of these references refer to the same system involved in designating aircraft classes. This system is then used to develop the specific designations assigned to each type of aircraft operated by the Navy. The F3F-4, TBF-1, AD-3, PBY-5A, A-4, A-6E, and F/A-18C are all examples of specific types of naval aircraft designations, which were developed from the Aircraft Class Designation System. Aircraft Class Designation System Early Period of Naval Aviation up to 1920 The uncertainties during the early period of naval aviation were reflected by the problems encountered in settling on a functional system for designating naval aircraft. -

CATALINA 84 REV 23A C13 FINAL PRINT C552 141015.Cdr

ISSUE No 84 - AUTUMN/WINTER 2015 A fantastic view of Miss Pick Up overflying Operation World First's Faxa Sø lake site in Greenland during July this year. Expedition Leader Neal Gwynne is standing on the shoreline. Read more about this special event inside Alan Halewood £1.75 (free to members) PHOTOPAGE DOWN BY THE SEASIDE IN 2015 Several of our display commitments during 2015 were at seafront locations and here are photos taken at one of them – Llandudno in North Wales. Our back cover shows the excellent publicity poster for the show featuring a certain well- known flying boat! Often, local topography combined with a long focal length lens can produce unusual perspectives such as this one taken at the May display. Most of the crowd are out of view on the prom’ This view shows Miss Pick Up down low over the sea during its run in toward the crowd line – it could almost be the North Sea in 1945! 2 ISSUE No 84 - AUTUMN/WINTER 2015 EDITORIAL ADDRESSES Editor Membership & Subs Production Advisor David Legg Trevor Birch Russell Mason 4 Squires Close The Catalina Society 6 Lower Village Road Crawley Down Duxford Airfield Sunninghill Crawley Cambs Ascot West Sussex CB22 4QR Berkshire RHI0 4JQ ENGLAND SL5 7AU ENGLAND ENGLAND Editor: [email protected] Web Site: www.catalina.org.uk Webmaster: Mike Pinder Operations Web Site: www.catalinabookings.org The Catalina News is published twice a year by the Catalina Society and is for private circulation only within the membership of the Society and interested parties, copyright of The Catalina Society with all rights reserved. -

AIR FORCE RENAISSANCE? Canada Signals a Renewed Commitment to Military Funding THINK CRITICAL MISSIONS

an MHM PUBLisHinG MaGaZine 2017 edition Canada’s air ForCe review BroUGHt to yoU By www.skiesMaG.CoM [INSIDE] RCAF NEWS YEAR IN REVIEW RETURN TO THE “BIG 2” BAGOTVILLE’S 75TH FLYING RED AIR VINTAGE WINGS RESET AIR FORCE RENAISSANCE? CANADA SIGNALS A RENEWED COMMITMENT TO MILITARY FUNDING THINK CRITICAL MISSIONS Equipped with cutting edge technology, all weather capability and unrivaled precision and stability in the harshest environments. Armed with the greatest endurance, longest range and highest cruise speed in its class. With maximum performance and the highest levels of quality, safety and availability to ensure success for demanding search and rescue operations - anywhere, anytime. H175 - Deploy the best. Important to you. Essential to us. RCAF Today 2017 1 Mike Reyno Photo 32 A RENAISSANCE FOR THE RCAF? The Royal Canadian Air Force appears to be headed for a period of significant renewal, with recent developments seeming to signal a restored commitment to military funding. By Martin Shadwick 2 RCAF Today 2017 2017 Edition | Volume 8 42 IN THIS ISSUE 62 20 2016: MOMENTS AND 68 SETTING HIGH STANDARDS MILESTONES The many important “behind the scenes” elements of the Canadian Forces The RCAF met its operational Snowbirds include a small group of 431 commitments and completed a number Squadron pilots known as the Ops/ of important functions, appearances and Standards Cell and the Tutor SET. historical milestones in 2016. Here, we revisit just a few of the year’s happenings. By Mike Luedey 30 MEET THE CHIEF 72 PLANES AND PASSION RCAF Chief Warrant Officer Gérard Gatineau’s Vintage Wings is soaring Poitras discusses his long and satisfying to new heights, powered by one of its journey to the upper ranks of the greatest assets—the humble volunteer. -

WINTER 2010 - Volume 57, Number 4 the Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A

WINTER 2010 - Volume 57, Number 4 WWW.AFHISTORICALFOUNDATION.ORG The Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS and other air power pioneers, the Air Force Historical All members receive our exciting and informative Foundation (AFHF) is a nonprofi t tax exempt organization. Air Power History Journal, either electronically or It is dedicated to the preservation, perpetuation and on paper, covering: all aspects of aerospace history appropriate publication of the history and traditions of American aviation, with emphasis on the U.S. Air Force, its • Chronicles the great campaigns and predecessor organizations, and the men and women whose the great leaders lives and dreams were devoted to fl ight. The Foundation • Eyewitness accounts and historical articles serves all components of the United States Air Force— Active, Reserve and Air National Guard. • In depth resources to museums and activities, to keep members connected to the latest and AFHF strives to make available to the public and greatest events. today’s government planners and decision makers information that is relevant and informative about Preserve the legacy, stay connected: all aspects of air and space power. By doing so, the • Membership helps preserve the legacy of current Foundation hopes to assure the nation profi ts from past and future US air force personnel. experiences as it helps keep the U.S. Air Force the most modern and effective military force in the world. • Provides reliable and accurate accounts of historical events. The Foundation’s four primary activities include a quarterly journal Air Power History, a book program, a • Establish connections between generations. -

RCAF Aircraft Types

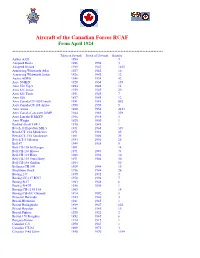

Aircraft of the Canadian Forces RCAF From April 1924 ************************************************************************************************ Taken on Strength Struck off Strength Quantity Airbus A320 1996 5 Airspeed Horsa 1948 1959 3 Airspeed Oxford 1939 1947 1425 Armstrong Whitworth Atlas 1927 1942 16 Armstrong Whitworth Siskin 1926 1942 12 Auster AOP/6 1948 1958 42 Avro 504K/N 1920 1934 155 Avro 552 Viper 1924 1928 14 Avro 611 Avian 1929 1945 29 Avro 621 Tutor 1931 1945 7 Avro 626 1937 1945 12 Avro Canada CF-100 Canuck 1951 1981 692 Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow 1958 1959 5 Avro Anson 1940 1954 4413 Avro Canada Lancaster X/MP 1944 1965 229 Avro Lincoln B MkXV 1946 1948 3 Avro Wright 1925 1930 1 Barkley-Grow T8P-1 1939 1941 1 Beech 18 Expeditor MK 3 1941 1968 394 Beech CT-13A Musketeer 1971 1981 25 Beech CT-13A Sundowner 1981 1994 25 Beech T-34 Mentor 1954 1956 25 Bell 47 1948 1965 9 Bell CH-139 Jet Ranger 1981 14 Bell CH-136 Kiowa 1971 1994 74 Bell CH-118 Huey 1968 1994 10 Bell CH-135 Twin Huey 1971 1994 50 Bell CH-146 Griffon 1994 99 Bellanca CH-300 1929 1944 13 Blackburn Shark 1936 1944 26 Boeing 247 1940 1942 8 Boeing CC-137 B707 1970 1994 7 Boeing B-17 1943 1946 6 Boeing B-47B 1956 1959 1 Boeing CH-113/113A 1963 18 Boeing CH-47C Chinook 1974 1992 8 Brewster Bermuda 1943 1946 3 Bristol Blenheim 1941 1945 1 Bristol Bolingbroke 1939 1947 626 Bristol Beaufort 1941 1945 15 Bristol Fighter 1920 1922 2 Bristol 170 Freighter 1952 1967 6 Burguss-Dunne 1914 1915 1 Canadair C-5 1950 1967 1 Canadair CX-84 1969 1971 3 Canadair F-86 Sabre