Nick Cave Explains the Truth Behind His Staged Documentary '20,000 Days on Earth'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pm Nick Cave 14.02.2013

FKP Scorpio Konzertproduktionen GmbH Große Elbstr. 277 a · 22767 Hamburg Tel. (040) 853 88 888 · www.fkpscorpio.com PRESSEMITTEILUNG 14.02.2013 Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds am 10. November in der Sporthalle Nick Cave begnügt sich bekanntermaßen nicht damit nur ein künstlerisch-kreatives Feld zu bestellen. Im Gegenteil: die Vielfältigkeit seines Saatguts ist in den letzten Jahren immer noch gewachsen. So tat Cave sich in den letzten Jahren nicht nur als Buchautor hervor, sondern wagte sich auch an das Schreiben von Drehbüchern und lieferte gemeinsam mit seinem Bandkollegen Warren Ellis die Filmmusik zu Andrew Dominiks „Die Ermordung des Jesse James durch den Feigling Robert Ford“. Im Konglomerat seiner Nebenprojekte nicht zu vergessen: sein musikalisches Nebenprojekt Grinderman, mit dem er zeigte, dass er sich auch vortrefflich auf sachlich-nüchternen Rock’n’Roll versteht. Egal welches Feld Cave gerade beackert, Beifall von Fans und Presse erntet er dafür immer. Aktuell hat seine Band Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds oberste Priorität: Mitte Februar erscheint das neue Album „Push The Sky Away“. Ein Werk subtiler Schönheit, über das Cave sagt: „Wenn ich die abgedroschene Metapher verwenden wollte, dass Alben wie Kinder sind, dann wäre „Push The Sky Away“ das Geisterbaby im Brutkasten und Warrens Loops wären der Rhythmus seines winzigen, zitternden Herzens“. Im Herbst 2013 kommen Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds auf Deutschlandtournee. Die Zeiten, da man sich im Anschluss eines Konzerts, Geschichten eines Frontmanns erzählte, der vollkommen zugedröhnt von der Bühne gestürzt war oder sich minutenlang auf dem Boden gewälzt hatte, gehören der Vergangenheit an. Der Familienvater Cave hat den Drogen lange abgeschworen. -

Ellie Wyatt Is a BAFTA Nominated Songwriter, a Composer, String

Ellie Wyatt is a BAFTA nominated songwriter, a composer, string arranger and violinist whose music and songs have been used on a wide array of Film, TV and advertising. She collaborates with talented producers and singers from all over Europe. Film/ TV /Game Song Synch credits include: Promos- Desperate Housewives, E!, Wimbeldon, Shameless and Showtime. TV- Black Mirror, Stranger Things, Harlots, Greys Anatomy, Degrassi, Men In Trees, The Ghost Whisperer, South of Nowhere, MTV, Wimbeldon, The Alan Carr Show Theme Movies-Touch The Wall, Haze the trailer for Disney’s Cars2 and Assassins Creed. Kids TV: Scored Music and Theme Song for BBC Worldwide mixed media pre-school science show Kit and Pup (52 episodes). Songs and series scored music for CBeebies show Tee & Mo (50 episodes) with BAFTA winning animation company Plugin Media. The animated song ‘Are we ready to go’ won a 2016 award at the international festival Prix Jeunesse and the animated song ‘Come On, Get Up’ was nominated for a 2016 BAFTA for best children’s shortform. 28 songs, including theme song, for CBeebies in house series Feeling Better (26 episodes). Theme Song and integrated songs for BBC Scotland production Molly and Mack. Theme re-brand and various songs for Milkshake TV. Songs for Totems, Sesame Street. Various stand alone songs for CBeebies House and Sesame Street. Songs and nursery rhymes for Tiny Pop. Music for the 2016 BAFTA winning website for CBeebies Big & Small. Advertising campaign credits include: Instax Sponsors New Girl on E4, Nivea, Evian, Monoprix, VW, Chanel, Johnsons, HugoBoss, YSL, Peugeot, Lancome, Nokia, Aveeno, Sears, Auchann, Safeway, Amex, Carnival, Comcast, Powerade, Douwe Egberts Senseo and L’Or, RBS, Antibiotics for Public Health England and Transport for London. -

Dr. Richard Brown Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the Lyrics of Nick Cave

Student ID: XXXXXX ENGL3372: Dissertation Supervisor: Dr. Richard Brown Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the Lyrics of Nick Cave Table of Contents Introduction 2 Chapter One – ‘I went on down the road’: Cave and the holy blues 4 Chapter Two – ‘I got the abattoir blues’: Cave and the contemporary 15 Chapter Three – ‘Can you feel my heart beat?’: Cave and redemptive feeling 25 Conclusion 38 Bibliography 39 Appendix 44 Student ID: ENGL3372: Dissertation 12 May 2014 Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the lyrics of Nick Cave Supervisor: Dr. Richard Brown INTRODUCTION And I only am escaped to tell thee. So runs the epigraph, taken from the Biblical book of Job, to the Australian songwriter Nick Cave’s collected lyrics.1 Using such a quotation invites anyone who listens to Cave’s songs to see them as instructive addresses, a feeling compounded by an on-record intensity matched by few in the history of popular music. From his earliest work in the late 1970s with his bands The Boys Next Door and The Birthday Party up to his most recent releases with long- time collaborators The Bad Seeds, it appears that he is intent on spreading some sort of message. This essay charts how Cave’s songs, which as Robert Eaglestone notes take religion as ‘a primary discourse that structures and shapes others’,2 consistently use the blues as a platform from which to deliver his dispatches. The first chapter draws particularly on recent writing by Andrew Warnes and Adam Gussow to elucidate why Cave’s earlier songs have the blues and his Christian faith dovetailing so frequently. -

NICK CAVE &The Bad Seeds

DAustrAlisk A NyA ZeeläWNNdskA väNskApsföreNiNgeN www.AustrAlieN-Ny AZeelANd.se UNDER NR 1 / 2013 NICK CAVE & THE BAD FISKEÄVENTYR SEEDS i Auckland intervju + recension Husbils- SEMESTER på Nya Zeeland THE GRAND B.Y.O, Barbie & Beetroot? CIRCLE Nyheter & medlemsförmåner Tasmanien runt The Swan Bell Tower / Whitsundays Hells Gate i Rotorua / Stewart Island VÄNSKAPSFÖRENINGENS NYA HEMSIDA På hemsidan hittar du senaste nytt om evenemang, nyheter, medlemsförmåner och tips. Du kan läsa artiklar, reseskildringar och få information om working holiday, visum mm. Besök WWW.AUSTRalien-nYAZEELAND.SE I AUSTRALISKA NYA ZEELÄNDSKA VÄNSKAPSFÖRENINGEN Medlemsavgift 200:- kalenderår. Förutom vår medlemstidning erhåller du en mängd rabatter hos företag och föreningar som vi samarbetar med. Att bli medlem utvecklar och lönar sig! Inbetalning till PlusGiro konto 54 81 31-2. Uppge Bli namn, medlem ev. medlemsnummer och e-postadress. 2 Det känns The Grand Circle - Tasmanian runt 5 & att få skriva årets första ledare i detta nr 1 år 2013. Nytt år och ny layout på Down Under, dessutom en massa spän- nande aktiviteter på gång i kalendern.inspirerande Jag vet att många av er un- der våra kallaste månader, november till februari varit på besök i våra länderfantastiskt Australien och kul Nya Zeeland. Jag tycker det är lika spännande varje gång att få höra om vad ni upplevt och varit med om. Skriv gärna och berätta om era resor till oss på Down Under. Den 10 februari hade vi årsmöte i Lund, ett möte som även inne- höll en spännande föreläsning av vår ordförande Erwin Apitzsch. Föreningens samarbete med Studiefrämjandet gjorde att vi kunde använda oss av deras lokaler, något vi är mycket tacksamma över. -

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds - Skeleton Tree - Slipper Nytt Album Og Film I September

02-06-2016 17:12 CEST NICK CAVE AND THE BAD SEEDS - SKELETON TREE - SLIPPER NYTT ALBUM OG FILM I SEPTEMBER NICK CAVE AND THE BAD SEEDS NYTT ALBUM "SKELETON TREE" SLIPPES 09.09 "ONE MORE TIME WITH FEELING" – FILMPREMIERE 08.09 I dag annonserer Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds slippet av sitt nye album "Skeleton Tree", deres sekstende studioalbum, som slippes både fysisk og digitalt 9. september via Kobalt / Playground Music. "Skeleton Tree" blir oppfølgeren til et av de mest kritikerroste og kommersielt suksessfulle albumene til Bad Seeds i nyere tid, "Push The Sky Away" fra 2013. Arbeidet med "Skeleton Tree" begynte i 2014, når bandet hadde sessions i Retreat Studios i Brighton, etterfulgt av sessions i La Frette Studios i Frankrike på slutten av året i 2015. Albumet ble mikset ferdig i AIR Studios i London i begynnelsen av 2016. Første mulighet for å høre de nye sangene fra albumet vil være i forbindelse med visningen av filmen "One More Time With Feeling" som er regissert avAndrew Dominik (Chopper, The Assassination Of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Killing Them Softly). Filmen har kinopremiere verden over den 8. september, dagen før "Skeleton Tree" slippes. "One More Time With Feeling" var opprinnelig tiltenkt som en konsertfilm. Med Dominik sin hjelp utviklet den seg langt mer i retning av å være et slags bakteppe til skrive- og innspillingsprosessen til albumet. Her flettes bandets opptredener sammen med intervjuer og stemningsbilder filmet av Dominik, akkompagnert av Nick Cave sin fortellerstemme og improviserte grubling. Filmen er skutt i svart-hvitt, i både 3D og 2D. -

Vinyls-Collection.Com Page 1/64 - Total : 2470 Vinyls Au 03/10/2021 Collection "Pop/Rock International" De Lolivejazz

Collection "Pop/Rock international" de lolivejazz Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage 220 Volt Mind Over Muscle LP 26254 Pays-Bas 50 Cent Power Of The Dollar Maxi 33T 44 79479 Etats Unis Amerique A-ha The Singles 1984-2004 LP Inconnu Aardvark Aardvark LP SDN 17 Royaume-Uni Ac/dc T.n.t. LP APLPA. 016 Australie Ac/dc Rock Or Bust LP 88875 03484 1 EU Ac/dc Let There Be Rock LP ALT 50366 Allemagne Ac/dc If You Want Blood You've Got I...LP ATL 50532 Allemagne Ac/dc Highway To Hell LP ATL 50628 Allemagne Ac/dc High Voltage LP ATL 50257 Allemagne Ac/dc High Voltage LP 50257 France Ac/dc For Those About To Rock We Sal...LP ATL 50851 Allemagne Ac/dc Fly On The Wall LP 781 263-1 Allemagne Ac/dc Flick Of The Switch LP 78-0100-1 Allemagne Ac/dc Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap LP ATL 50 323 Allemagne Ac/dc Blow Up Your Video LP Inconnu Ac/dc Back In Black LP ALT 50735 Allemagne Accept Restless & Wild LP 810987-1 France Accept Metal Heart LP 825 393-1 France Accept Balls To The Walls LP 815 731-1 France Adam And The Ants Kings Of The Wild Frontier LP 84549 Pays-Bas Adam Ant Friend Or Foe LP 25040 Pays-Bas Adams Bryan Into The Fire LP 393907-1 Inconnu Adams Bryan Cuts Like A Knife LP 394 919-1 Allemagne Aerosmith Rocks LP 81379 Pays-Bas Aerosmith Live ! Bootleg 2LP 88325 Pays-Bas Aerosmith Get Your Wings LP S 80015 Pays-Bas Aerosmith Classics Live! LP 26901 Pays-Bas Aerosmith Aerosmith's Greatest Hits LP 84704 Pays-Bas Afrika Bambaataa & Soulsonic F.. -

Kiff Aarau We Keep You in the Loop

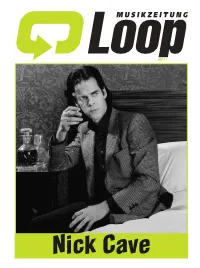

SEP.17 Nick Cave EINSCHLAUFEN Betrifft: Sepia-Tinte, Siff und Samt Impressum Nº 07.17 Manchmal sind es tatsächlich nur Menschen Als Berlin Ende 1989 mit dem Mauerfall den DER MUSIKZEITUNG LOOP 20. JAHRGANG und Orte. Eine flüchtige Kombination aus Bio- Frontstadt-Status verlor, mochte auch unser Ti- grafie und Geografie, die sich mit Bedeutung telheld nicht mehr dort leben. Sein Ruhm, den er P.S./LOOP Verlag auflädt. William S. Burroughs in Tanger. Jörg sich inzwischen erarbeitet hatte, folgte ihm al- Langstrasse 64, 8004 Zürich Fauser in Istanbul. Malcolm Lowry in Mexiko. lerdings auch auf seinem Schlingerkurs um den Tel. 044 240 44 25, Fax. …27 Fixe Bezugspunkte in einem Atlas der Sucht, Globus. Und wurde einer Transformation unter- www.loopzeitung.ch die freilich nicht nur endlosen Exzess, sondern worfen. Der Siff der frühen Jahre verschwand, auch Phasen von geradezu manischer Kreativi- zur inzwischen sorgsam gekämmten und ge- Verlag, Layout: Thierry Frochaux tät markieren. Die zugehörigen Romane: «In- tönten Frisur trug man gut sitzende Anzüge, [email protected] terzone», «Rohstoff», «Under the Volcano». diskrete Hemden und hin und wieder gar eine In diese Reihe der Vertriebenen – oder um einen Krawatte. Unter der samtenen Oberfläche hin- Administration, Inserate: Manfred Müller musikalisch-technischen Begriff zu verwenden: gegen brodelte es weiter. Leidenschaftlich arran- [email protected] aus dem Leben Ausgekoppelten – gehört auch gierte Liebe, biblischer Furor und eine archaisch Nick Cave. Ein paar Jahre früher war auch anmutende Weltsicht kondensierten zu Liedern, Redaktion: Philippe Amrein (amp), David Bowie in der Hauptstadt des Heroins die genau das tun, was man von ihnen erwartet: Benedikt Sartorius (bs), Koni Löpfe unterwegs und hat dort wegweisende Alben Sie zerwühlen das Herzfett der Hörerschaft. -

20'000 Days on Earth

20’000 DAYS ON EARTH Ein Film von Jane Pollard und Iain Forsyth UK, 2013, 95 Minuten Verleih: Xenix Filmdistribution GmbH Tel. 044 296 50 40 Fax 044 296 50 45 [email protected] http://www.xenixfilm.ch Presse: Anna-Katharina Straumann [email protected] www.xenixfilm.ch Start: 06. November 2014 Bilder sind auf www.xenixfilm.ch erhältlich. KURZINHALT Es ist der 20.000ste Tag im Leben von Nick Cave – er beginnt mit einem Weckerklingeln und endet mitten in seiner Seele. Was bedeutet es, sich ununterbrochen im kreativen Prozess zu befinden? Wie füllt man sein Leben fernab der Bühne und was geschieht bei dem Schritt darauf? Und woraus besteht ein Leben gerade rückblickend überhaupt? Auf der Couch eines Therapeuten oder im Auto mit Wegbegleitern wie Kylie Minogue und Blixa Bargeld nähert sich Nick Cave solch essentiellen Fragen. Der Blick in das Innenleben dieser Ikone liefert schliesslich magische und beglückende Einsichten in das menschliche Dasein. Dabei bleibt zu jeder Zeit unklar, ob es sich um gefilmte Realität oder geniale Inszenierung handelt. Das Kinodebüt des Künstlerduos Iain & Jane ist ein sorgfältig durchkomponiertes, Genre- sprengendes Werk, changierend zwischen Doku und Fiktion. Es ist nicht nur ein atemberaubendes Denkmal für den Kultmusiker Nick Cave, sondern auch ein Porträt rastloser Kreativität und eine ganz universelle Poesie des Lebens. Ein cineastisch und emotional inspirierendes Kinoerlebnis. PRESSENOTIZ 20.000 DAYS ON EARTH war in diesem Jahr eines der Besucher- und Kritiker- Highlights auf internationalen Festivals, darunter das Sundance Film Festival (Auszeichnungen für Beste Regie und Besten Schnitt) und die Berlinale. Das Künstlerduo Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard zaubert in seinem Langfilmdebüt eine Kraft auf die Leinwand, die ihresgleichen sucht. -

Aesthetica-September2014

Intimacies of an Icon Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard stage a fictionalised 24 hours in the life of Nick Cave, replacing traditional rockumentary aesthetics with an exploration of how we spend our time on earth. Songwriter, musician, author, screenwriter and composer, Nick Cave, is a true rock star best known for his mesmerising live performances and bizarre yet haunting lyrics. For 20,000 Days on Earth the famously camera-shy Cave collaborates with video artists turned feature film directors, Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard, in a production which tracks a fictional 24 hours in Cave’s real life amongst his family and friends. Cave has described this day as “more real and less real, more true and less true, more interesting and less interesting than my actual day, depending on how you look at it.” In under two hours we follow Cave through his home town of Brighton and his relationships with his family, through writing and rehearsing, performing and recording; through discussions with previous musical partners Kylie Minogue and Blixa Bargeld and actor Ray Winstone; and we reach into his past through sessions with psychoanalyst Darian Leader, and time spent in Cave’s archive – brought over from Australia and re- structured for the film. While the personalities and conversations of 20,000 Days on Earth are genuine, it is not a docu-film; the situations and locations are wholly staged, a decision made by Forsyth and Pollard who affirm that they “never wanted it to look any other way.” Having always explored musicians, music and performance in a factual, documentary-esque manner in their visual art, the directors had long since identified a problem with realism in documentaries. -

Nick Cave Lleva Siete Años Inmerso En La Fase Más Prolífica De Su Carrera

Entrevista ‘RS’ ESCLAVO de la q MUSANick cave lleva siete años inmerso en la fase más prolífica de su carrera. HeNRY ROLLiNS se sienta con su viejo amigo para hablar sobre Push the sky away, el disco que presenta el 25 de mayo en el Primavera Sound de Barcelona. por Henry Rollins Fotografía Bleddyn Butcher uando se piensa en Nick Cave, uno suele estar atrapado entre una banal verborrea repleta de epítetos o una profunda incapacidad para encontrar las palabras adecuadas. Desde el proto emo de los Boys Next Door o la diabólica vulgaridad de Birthday Party al estilo más desgarrador de su proyecto paralelo Grinderman y, sobre todo, junto a sus viejos compañeros de Bad Seeds, Nick Cave lleva componiendo y grabando música desde los 70. Todo lo que ha hecho merece ser escuchadoC y debería ser obligatorio asistir a sus conciertos. Tanto en las letras más salvajes de su primera época como en sus arrebatadoras composiciones más actuales, Cave ha demostrado un profundo compromiso con la obra. Uno llega a la conclusión de que ha aceptado el hecho de que su papel en el mundo es el de servir a la musa y que ese hecho es más poderoso que ninguna otra cosa. Ahora, en su cuarta década de actividad creativa, que se ha ramificado en diferentes géneros como guiones y novelas, sigue intentando encontrar algo. www.elboomeran.com rollingstone.es 99 Entrevista ‘RS’ NICK CAVE En 2013, Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds han hubiera parado hace años. Pero en cuanto acabo empiezo a componer. Me levanto por las mañanas, De ninguna manera quiero que creas que te publicado su decimoquinto disco, Push the sky una cosa empiezo con otra que se me presenta de me voy a la oficina, empiezo a componer y me ocu- estoy insultando, pero me parece bastante away. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds Electrifying Austin City

NICK CAVE & THE BAD SEEDS ELECTRIFYING AUSTIN CITY LIMITS DEBUT New Episode Premieres November 1st on PBS Austin, TX—October 31, 2014—Austin City Limits (ACL) presents an electrifying hour with Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds, one of the most exhilarating live acts in music. The noir- rock outfit make their ACL debut in an hourlong performance with a memorable career-wide set powered by dark songs of love, death, God and fate. The episode premieres Saturday, November 1st at 9pm ET/8pm CT as part of ACL's milestone Season 40. ACL airs weekly on PBS stations nationwide (check local listings for times) and full episodes are made available online for a limited time at http://video.pbs.org/program/austin-city-limits/ immediately following the initial broadcast. The show's official hashtag is #acltv40. Nick Cave is one of contemporary music’s most powerful personalities, and the Australian-born iconoclast takes the ACL stage with his longtime band for an unforgettable appearance. The masterful nine-song set features highlights from their 30-year career, spanning the 1984 debut to 2013's universally-acclaimed Push the Sky Away, their fifteenth studio album. The black-clad Cave stalks the ACL stage with primal energy and explores the thin line between light and darkness with selections from his fire-and-brimstone universe, spouting scripture- scaled narratives and anti-anthems from his rogue's gallery of characters. “Tupelo”, a twisted take on the mythos surrounding Elvis Presley, has the singer-songwriter ranting like an evangelist fallen from grace and intent on clawing his way back.