Opskrif Hier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1839 Revival Part 3 - Kilsyth

1839 Revival Part 3 - Kilsyth Of the 1839-40 revivals in Scotland the best known is the work of God at St Peter’s In Dundee where Robert Murray McCheyne was minister. However the man who was the first instrument God used there was William Chalmers Burns. Burns, aged 24, was a friend of McCheyne and newly licenced as a probation minister of the Church of Scotland. When the revival broke out in Dundee, McCheyne was away on his now famous trip to Israel, where he was investigating mission to the Jews, and W C Burns stood in for him at St Peter’s from April 1839. Though “a mere stripling” he was much loved by the congregation there. Description of W C Burns. A church officer wrote of him at the time “Scarcely had Mr Burns entered on his work in St Peter’s here, when his power as a preacher began to be felt. Gifted with a solid and vigorous understanding, possessed of a voice of vast compass and power, unsurpassed even by that of Mr Spurgeon – and withal fired with an ardour so intense and an energy so exhaustless that nothing could damp or resist it. Crowds flocked to St Peter’s from all the country round. Wherever Mr Burns preached a deep impression was produced on his audience and it was felt to be impossible to remain unconcerned under the impassioned earnestness of his appeals.” (McMullen p 30.) WC Burns was the son of W Burns, the minister at Kilsyth and in July 1839 he returned to help his father with the communion season there. -

Histories of Revival

I must confess, again, that before coming to this church I hadn’t studied much about Revival. Of course, I had heard about, read little pieces on the subject, … but that was as far as it went, - I hadn’t put my heart into it. I suppose, to a certain degree, that is all it was, - just a study, - … and I never considered to have it on my agenda to set aside specific time to pray for revival as we do on a Monday evening, and as we are considering on Sunday evenings. I now consider it part of my responsibility as a Christian to address God regarding the subject of another visitation of the Holy Spirit upon God’s people. That is what we call true Revival. Martyn Lloyd-Jones teaches us, as we look at Joshua 4:21-24 to ‘come back to the stones’, 21 And he spake unto the children of Israel, saying, When your children shall ask their fathers in time to come, saying, WHAT MEAN THESE STONES? 22 Then ye shall let your children know, saying, Israel came over this Jordan on dry land. 23 For the LORD your God dried up the waters of Jordan from before you, until ye were passed over, as the LORD your God did to the Red sea, which he dried up from before us, until we were gone over: 24 That all the people of the earth might know the hand of the LORD, that it is mighty: that ye might fear the LORD your God for ever. -

The Power to Save

The Power to Save A history of the gospel in China Bob Davey EP Books Faverdale North, Darlington, DL3 0PH, England e-mail: [email protected] web: www.epbooks.org EP Books USA P. O. Box 614, Carlisle, PA 17013, USA e-mail: [email protected] web: www.epbooks.us © R. W. Davey 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise, without the prior permission of the publishers. First published 2011 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data available ISBN 13: 978 0 85234 743 0 ISBN: 0 85234 743 X Printed and bound in the UK by Charlesworth, Wakefield, West Yorkshire Contents Page List of illustrations 8 Foreword by Sinclair Ferguson 11 Preface 17 1. Chinas roots 21 2. Christianity in China up to AD 1800 28 3. Robert Morrison, the pioneer of the gospel to China, 1807 37 4. Charles Gutzlaff, pioneer explorer and missionary to China 53 5. Liang Afa: the first Chinese Protestant evangelist and pastor 69 6. Hudson Taylor: the making of a pioneer missionary, 183253 78 7. Hudson Taylor: up to the formation of the CIM, 185465 91 8. Hudson Taylor: establishing the China Inland Mission, 186575 107 9. Hudson Taylor: the triumph of faith, 18751905 120 10. The beginnings of a new century, 19001910 136 11. Birth of the republic and World War, 191020 151 12. Emergence of Chinese Christian leaders, 192030 163 13. Revivals, 193037 179 14. Awakening among university students, 193745 195 15. -

Son of a Mother's

by Timothy Tow an autobiography 2 Son of a Mother’s Vow Son of a Mother’s Vow © 2001 Rev. (Dr.) Timothy Tow 9A Gilstead Road, Singapore 309063. ISBN 981-04-2907-X Published by FEBC Bookroom 9A Gilstead Road, Singapore 309063. http://www.lifefebc.com Printed in the Republic of Singapore. Cover design by Charles Seet. Contents 3 Contents Acknowledgement ......................................................................... 6 Prologue ......................................................................................... 7 1. Discovering Our Roots 1815-1868 ................................................................................. 9 2. Childhood Memories of China 1920-1926 ............................................................................... 29 3. Exodus To Nanyang (The South Seas) 1926-1935 ............................................................................... 45 4. The Singapore Pentecost 1935 ........................................................................................ 63 5. No Failure, No Success 1936-1948 ............................................................................... 85 6. Faith Of Our Fathers 1948-1950 ............................................................................. 125 7. Mother’s Vow Fulfilled 1950 ...................................................................................... 131 8. Beginnings Of A Young Pastor 1950-1951 ............................................................................. 138 9. By Sword and Trowel 1951-1956 ............................................................................ -

“B-P Distinctives - Historical Roots”

January to March 2014 Teenz RPG Series on “B-P Distinctives - Historical Roots” Do pray for the Holy Spirit’s guidance before you begin your devotional time, for unless the Spirit reveals the meaning, we cannot understand scripture (1 Corinthians 2:10). Then you must read the scripture text; please don’t be tempted to read the devotional alone without reading the Bible. Memorizing the scripture text will help you meditate upon it (Psalm 1:2), even long after you have finished your devotional time. After reading the devotional, always end with self-reflection: compare yourself against the standard of God’s Word, and humbly yield to the Holy Spirit to direct you towards that standard (James 1:23-25). Be ye doers of the Word, not hearers only! At the end of this series, may you be able to say as David said “O God, thou art my God; early will I seek thee: my soul thirsteth for thee, my flesh longeth for thee in a dry and thirsty land, where no water is.” (Psalm 63:1) May all glory be God’s alone! Dn Milton Ang On behalf of the Teenz RPG committee WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 1 Psalm 78:7 Memorise Psalm 78:7 “That the generation to come might know them” IS HISTORY IMPORTANT? The Bible is replete with the history of the nation of Israel and how God dealt with His people. The history of the church as recorded for us, starting from the book of Acts and through the corridor of time to the Reformation is just as precious and instructive. -

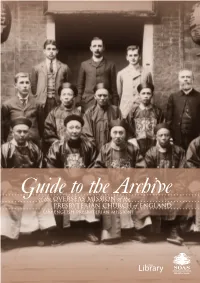

Guide to the Archive of the English Presbyterian Mission

Guide overseas to missionthe rchive of the Aof the presbyterian church of england ( the english presbyterian mission) LibSOASrary background history organisational history One of the first acts of the newly-established Presbyterian Church in England (PCE) in 1844 was to set up a Foreign Missions Committee (FMC) to “institute foreign missions in connection with this Church as speedily as possible.”1 China was chosen as the first mission field for the English Presbyterian Mission (EPM), due in part to the interest in China engendered by the Opium Wars and to the fact that the Free Church of Scotland, with whom the PCE was in alliance, was not in a position in that time to extend its missionary work to China. Many English Presbyterian missionaries came in fact from Scotland. The first missionary, A country William Chalmers Burns (1815-1868), school teacher in the Hakka- who hailed from the Scottish borders, was speaking region appointed to China in 1847. In 1878 the of south-east Women’s Missionary Association (WMA) China, c.1900s was founded, following the sending of the Ref: PCE/FMC Hakka Photographs, Church’s first single woman missionary, box 1, file 3 Catherine Maria Ricketts (1841-1907), to Swatow [Shantou] in present-day Guangdong province. The WMA functioned as an independent unit within the overall framework of the Presbyterian Church of England2 until 1925, when FRONT COVER PICTURE: Photograph taken to a union between the FMC and the WMA was ratified. The WMA mark the thirtieth became part of the FMC and women were given equal representation anniversary, in 1907, with men on the FMC Executive while retaining a home organisation of the ordination in the Presbyterian Church of with certain responsibilities, notably fundraising and training. -

The Protestant Missionaries As Bible Translators

THE PROTESTANT MISSIONARIES AS BIBLE TRANSLATORS: MISSION AND RIVALRY IN CHINA, 1807-1839 by Clement Tsz Ming Tong A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Religious Studies) UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) July 2016 © Clement Tsz Ming Tong, 2016 ABSTRACT The first generation of Protestant missionaries sent to the China mission, such as Robert Morrison and William Milne, were mostly translators, committing most of their time and energy to language studies, Scripture translation, writing grammar books and compiling dictionaries, as well as printing and distributing bibles and other Christian materials. With little instruction, limited resources, and formidable tasks ahead, these individuals worked under very challenging and at times dangerous conditions, always seeking financial support and recognition from their societies, their denominations and other patrons. These missionaries were much more than literary and linguistic academics – they operated as facilitators of the whole translational process, from research to distribution; they were mission agents in China, representing the interests and visions of their societies and patrons back home. Using rare Chinese Bible manuscripts, including one that has never been examined before, plus a large number of personal correspondence, journals and committee reports, this study seeks to understand the first generation of Protestant missionaries in their own mission settings, to examine the social fabrics within which they operated as “translators”, and to determine what factors and priorities dictated their translation decisions and mission strategies. Although Morrison is often credited with being the first translator of the New Testament into Chinese, the truth of the matter is far more complex. -

21St CENTURY COMMENTING on COMMENTARIES: the BEST HELPS for UNDERSTANDING the BIBLE

21st CENTURY COMMENTING ON COMMENTARIES By Steven L. Martin 21st CENTURY COMMENTING ON COMMENTARIES THE BEST HELPS FOR UNDERSTANDING THE BIBLE WHO THIS BOOK IS FOR: 1. PASTORS AND ELDERS 2. MISSIONARIES 3. SEMINARY STUDENTS 4. SUNDAY SCHOOL TEACHERS 5. SMALL GROUP LEADERS 6. STUDENT MINISTRY LEADERS 7. CHURCH LIBRARIANS 8. HOME BIBLE STUDY LEADERS 9. LAY STUDENTS OF THE BIBLE 10. CAMPUS MINISTRY LEADERS 11. FAITHFUL DADS LEADING FAMILY DEVOTIONS ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ COPYRIGHT 2000, 2004, 2008, 2014 WWW.THELOGCOLLEGE.WORDPRESS.COM 21st CENTURY COMMENTING ON COMMENTARIES: THE BEST HELPS FOR UNDERSTANDING THE BIBLE WHO IS THIS MATERIAL SUPPOSED TO HELP ? If you are a Christian, whether a pastor, missionary, elder, Sunday School teacher, deacon, home Bible study leader, youth worker, church librarian, campus leader, or faithful husband and father, you will want to be a diligent student of the Bible. So I have compiled COMMENTING ON COMMENTARIES: THE BEST HELPS FOR UNDERSTANDING THE BIBLE for you. Pastor- teachers are spiritual leaders who must give an account to God for handling His Word (2nd Timothy 2:15) and leading His sheep (Hebrews 13:17), need to know the books that will best help you to thoroughly understand God's Word. In order for you to preach and teach it correctly, not to mention obey it carefully, you must understand it yourself. As a faithful Sunday School teacher who must handle God's Word with accuracy, you too need to know what books will give you the most help to meet your ministry needs. For you leading home Bible studies or student ministries, you must get to the heart of a book and make it clear to your people. -

“Times of Blessing” in Manchuria

“Times of Blessing” in Manchuria Rev. J. W e b s t e r betters from Moukden to the Church at Home February 17— April 30, 1908 T h i r d E d i t i o n S h a n g h a i M ethodist Publishing House 1909 PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION. It was anticipated that the second edition of this account of the revival in Manchuria would have met all demands, but so far from this being the case, a third and larger edition has been called for within a few months. In this new edition Mr. Webster hoped to have been able to add a supplementary letter describing the remarkable meetings that took place in Tieliling, but through pressure of other work he has found it impossible to do so, and the story is therefore reissued without alteration or addition. G . H . B o n d f i e l d . Shanghai, December 24th, 1908. ■ PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. It is a hopeful sign that a second edition of these Letters has been called for so speedily. Their testimony to the presence and power of the Holy Spirit in the churches in Manchuria is a challenge to every church in China to taste and see how gracious the Lord is. They are also a reminder to every missionary and every Chinese Pastor that the ordinary service and prayer- meeting and ministry may be the channels of such a measure of the divine grace as shall sweep away every obstacle and reveal to our Chinese Christians all the riches of their inheritance in Christ Jesus. -

臺勢教會 the Taiwanese Making of the Canada Presbyterian Mission

臺勢教會 The Taiwanese Making of the Canada Presbyterian Mission Mark A. Dodge Series in World History Copyright © 2021 by the author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200 C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware, 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in World History Library of Congress Control Number: 2020947486 ISBN: 978-1-64889-119-9 Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image: George Leslie Mackay, native pastors, and students during itinerating in North Formosa. Aletheia University Archives AUP0000111. Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Table of contents List of Figures v Acknowledgements vii A Note on the Romanization of Chinese ix Introduction: The Miracle Mission xiii Chapter 1 -

The Revival As a Dimension of Scottish Church History

The Revival as a Dimension of Scottish Church History REV. IAN A. MUIRHEAD, M.A., B.D. Though the motto of the city of Glasgow has been changed to suit the lifestyle of later generations of Glaswegians, as it is first on record in 1631 it takes the form: “Lord, let Glasgow flourichse through the preaching of they Word and praising thy Name”. 1 What happened when the ministers of Glasgow, or of any other Scottish city or village, gave themselves wholeheartedly to the “preaching of God’s Word”? Over considerable periods of time there might seem small enough result, but, now and then, a minister who had been preaching for years without visibly disturbing man, woman or beadle, found himself with a congregation which suddenly decided its minister was preaching more convincingly than ever before, which wept, groaned and moaned under his preaching, and which followed him to the manse in droves after sermon, seeking his counsel. The minister had a revival. That such revivals resulted from Scottish preaching cannot be gainsayed, for at times they received much notice, not always kindly, in the contemporary press, were productive of many pamphlets, some of them ill-natured, and in general were a theme of controversy, at times acrimonious, but that these revivals occurred frequently throughout a period of more than 150 years of Scottish church history, were widespread across the country, and were of significance as the continuing source of much that was effective in the life of the Scottish church, might not be readily suspected from our standard volumes on church history. -

Unforgettable Lessons from the Pilgrim's Progress

MARANATHA MESSENGER Weekly Newsletter of Private Circulation Only MARANATHA BIBLE-PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH 9 July 2017 “Present every man perfect in Christ Jesus” (Colossians 1:28) Address: 63 Cranwell Road, Singapore 509851 E-mail: [email protected] Sunday School: 9.45 am Sunday English / Chinese Worship Service: 10.45 am Sunday Chinese Worship Service: 7 pm Wednesday Prayer Meeting: 8.00 pm Unforgettable Lessons From The Pilgrim’s Progress Introduction This book will make a traveller of thee, If by its counsel thou wilt rule be; It will direct thee to the Holy Land, If thou wilt its directions understand: Yea, it will make the slothful active be; The blind also delightful things to see. John Bunyan In 1678, a godly puritan called John Bunyan was jailed for not conforming to the State requirement of only using the Book of Common Prayer in public worship and services (i.e. the Act of Uniformity in 1662) in Bedford. But in his 12 years in prison (in the prison cell, he asked for three books, namely, the Bible, a Concordance, and his much loved copy of the Book of Martyrs), he wrote an allegorical account of the life of a Christian in his quest from spiritual hopelessness to eternal life. He was a tinker and not a learned scholar like the other puritans (i.e. our Chinese version of the ar na gon nee man) but the content is of a excellent quality. The book, Pilgrim’s Progress gives a sound Puritanical view of Christianity. It is a legendary story of a believer’s journey to heaven.