Tragic Excess in Hamlet JEFFREY WILSON Downloaded from by Harvard Library User on 14 August 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 6 (2004) Issue 1 Article 13 Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood Lucian Ghita Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Ghita, Lucian. "Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 6.1 (2004): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1216> The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 2531 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

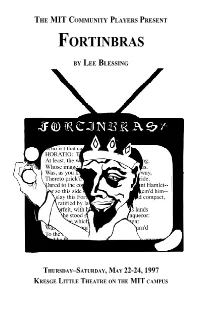

Fortinbras Program

THE MIT COMMUNITY PLAYERS PRESENT FORTINBRAS BY LEE BLESSING THURSDAY–SATURDAY, MAY 22-24, 1997 KRESGE LITTLE THEATRE ON THE MIT CAMPUS FORTINBRAS by Lee Blessing *Produced by special arrangement with Baker’s Plays The Persons of the Play Fortinbras ...................................... Steve Dubin Hamlet ........................................... Greg Tucker (S) Osric .............................................. Ian Dowell (A) Horatio........................................... Matt Norwood ’99 Ophelia .......................................... Erica Klempner (G) Claudius ........................................ Ben Dubrovsky (A) Gertrude ........................................ Anne Sechrest (affil) Laertes .......................................... Randy Weinstein (G) Polonius......................................... Peter Floyd (A, S) Polish Maiden 1............................. Alice Waugh (S) Polish Maiden 2............................. Anna Socrates Captain .......................................... Jim Carroll (A) English Ambassador ..................... Alice Waugh (S) Marcellus....................................... Eric Lindblad (G) Barnardo ....................................... Russell Miller ’00 The Scenes of the Play Act I: Elsinore — ten minute intermission — Act II: Still Elsinore (“S” indicates MIT staff member, “G” indicates graduate student, “A” indicates alumnus, and “affil” indicates affiliation with a member of the MIT community). Behind the Scenes Director............................................. Ronni -

The Story O/Hamlet

Thestory o/Hamlet The guards of ElsinoreCastle in Denmark have scen a Ghoston the bardcmenrs.Ir lookslike rhe fatherof prince -l'hev Hamlet who died only rwo monrhs bcfore. ask Horario.a youngnobleman and a friendof rhe prrnie, ro watchwith them and to talk to the Ghost.rffhen it appears. it doesnot speak, and disappears from sight. The new King of Denrnark Thc new King ofDenmark is Claudius,Hamler's uncle who hasjust ma[ied the Prince'smother, Gertrude.He allows Laertes,the son of his Lord Chamberlain,polonius. to rcturnto Parrsand urges Hamlel to castoff hismournine. Hamletis srill disrrcssed by his tarher'sdearh and decplv upsel that his mother has marriedbarelv t*o m,rnrh, afterwards.He longsfor deathand cundemnshis mother 'Fraihy, with the words, rhy nameis woman., Hamlet's lorying for death O! that this too too sol llesh toutrt nelt, ThalL)and r.sobe itseu inb a dn) . IInr ueary, shle,tat, and u,tfrolitubb Seemb mea fie usesof rhis;^orLl. Acrr Scii Poloniusbids farewellto hisson.advising him on howa youngman shouldbehave. Polonius's advice to his son l,leithera bonote4 nor a lealer be; Forloa ofi tosesbofi ilsetf dndfri.n t, And bonuA s dul\ th, eds ol hu,bart,j. Thr oboreall. to rhnc mv sctlbe rruc, And mustfoll@^, ttsthe nigtu rheda|, Thoucanst not fien befalse to anJma . Act r Sciii A ghostly rneeting Hamlet,meanwhile, has gone ro the castlebattlcments with Horatio. Vhen the Ghosrappears, he speaksro Hamlel, as the spirit of his dead farhcr. The Ghosrrells how he was l14 hr\ asks.llrrnltt 1o rcvtntle murdcrcd h\ (lhudius lnd lecp thc mcctingsccrer i""ii.-ii"*r",':i;.'. -

Literature (LIT) 1

Literature (LIT) 1 LITERATURE (LIT) LIT 113 British Literature i (3 credits) LIT 114 British Literature II (3 credits) LIT 115 American Literature I (3 credits) LIT 116 Amercian Literature II (3 credits) LIT 132 Introduction to Literary Studies (3 credits) This course prepares students to understand literature and to articulate their understanding in essays supported by carefully analyzed evidence from assigned works. Major genres and the literary terms and conventions associated with each genre will be explored. Students will be introduced to literary criticism drawn from a variety of perspectives. Course Rotation: Fall. LIT 196 Topics in Literature (3 credits) LIT 196A Topic: Images of Nature in American Literature (3 credits) LIT 196B Topic: Gothic Fiction (3 credits) LIT 196C Topic: American Detective Fiction (3 credits) LIT 196D Topic: The Fairy Tale (3 credits) LIT 196H Topic: Literature of the Supernatural (4 credits) LIT 196N Topic: American Detective Fiction for Nactel Program (4 credits) LIT 200C Global Crossings: Challenge & Change in Modern World Literature - Nactel (4 credits) Students in the course will read literature from a range of international traditions and will reach an understanding and appreciation of the texts for the ways that they connect and diverge. The social and historical context of the works will be explored and students will take from the course some understanding of the environments that produced the texts. LIT 200G Topic: Pulitzer Prize Winning Novels-American Life (3 credits) LIT 200H Topic: Poe and Hawthorne (3 credits) LIT 201 English Drama 900-1642 (3 credits) LIT 202 History of Film (3 credits) The development of the film from the silent era to the present. -

The Tragedy of Hamlet

THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET EDITED BY EDWARD DOWDEN n METHUEN AND CO. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON 1899 9 5 7 7 95 —— CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ix The Tragedy of Hamlet i Appendix I. The "Travelling" of the Players. 229 Appendix II.— Some Passages from the Quarto of 1603 231 Appendix III. Addenda 235 INTRODUCTION This edition of Hamlet aims in the first place at giving a trustworthy text. Secondly, it attempts to exhibit the variations from that text which are found in the primary sources—the Quarto of 1604 and the Folio of 1623 — in so far as those variations are of importance towards the ascertainment of the text. Every variation is not recorded, but I have chosen to err on the side of excess rather than on that of defect. Readings from the Quarto of 1603 are occa- sionally given, and also from the later Quartos and Folios, but to record such readings is not a part of the design of this edition. 1 The letter Q means Quarto 604 ; F means Folio 1623. The dates of the later Quartos are as follows: —Q 3, 1605 161 1 undated 6, For ; Q 4, ; Q 5, ; Q 1637. my few references to these later Quartos I have trusted the Cambridge Shakespeare and Furness's edition of Hamlet. Thirdly, it gives explanatory notes. Here it is inevitable that my task should in the main be that of selection and condensation. But, gleaning after the gleaners, I have perhaps brought together a slender sheaf. -

An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’S Hamlet

The Dilemma of Shakespearean Sonship: An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’s Hamlet The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mosley, Joseph Scott. 2017. The Dilemma of Shakespearean Sonship: An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33826315 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Dilemma of Shakespearean Sonship: An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’s Hamlet Joseph Scott Mosley A Thesis in the Field of Dramatic Arts for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2017 © 2017 Joseph Scott Mosley Abstract The aim of the proposed thesis will be to examine the complex and compelling relationship between fathers and sons in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. This study will investigate the difficult and challenging process of forming one’s own identity with its social and psychological conflicts. It will also examine how the transformation of the son challenges the traditional family model in concert or in discord with the predominant philosophy of the time. I will assess three father-son relationships in the play – King Hamlet and Hamlet, Polonius and Laertes, and Old Fortinbras and Fortinbras – which thematize and explore filial ambivalence and paternal authority through the act of revenge and mourning the death of fathers. -

The Idea of Mimesis: Semblance, Play, and Critique in the Works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 8-2012 The idea of mimesis: Semblance, play, and critique in the works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno Joseph Weiss DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Weiss, Joseph, "The idea of mimesis: Semblance, play, and critique in the works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno" (2012). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 125. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/125 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Idea of Mimesis: Semblance, Play, and Critique in the Works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy October, 2011 By Joseph Weiss Department of Philosophy College of Liberal Arts and Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois 2 ABSTRACT Joseph Weiss Title: The Idea of Mimesis: Semblance, Play and Critique in the Works of Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno Critical Theory demands that its forms of critique express resistance to the socially necessary illusions of a given historical period. Yet theorists have seldom discussed just how much it is the case that, for Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. -

The Place of Creative Writing in Composition Studies

H E S S E / T H E P L A C E O F C R EA T I V E W R I T I NG Douglas Hesse The Place of Creative Writing in Composition Studies For different reasons, composition studies and creative writing have resisted one another. Despite a historically thin discourse about creative writing within College Composition and Communication, the relationship now merits attention. The two fields’ common interest should link them in a richer, more coherent view of writing for each other, for students, and for policymakers. As digital tools and media expand the nature and circula- tion of texts, composition studies should pay more attention to craft and to composing texts not created in response to rhetorical situations or for scholars. In recent springs I’ve attended two professional conferences that view writ- ing through lenses so different it’s hard to perceive a common object at their focal points. The sessions at the Associated Writing Programs (AWP) consist overwhelmingly of talks on craft and technique and readings by authors, with occasional panels on teaching or on matters of administration, genre, and the status of creative writing in the academy or publishing. The sessions at the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC) reverse this ratio, foregrounding teaching, curricular, and administrative concerns, featur- ing historical, interpretive, and empirical research, every spectral band from qualitative to quantitative. CCCC sponsors relatively few presentations on craft or technique, in the sense of telling session goers “how to write.” Readings by authors as performers, in the AWP sense, are scant to absent. -

Armenian State Chamber Choir

Saturday, April 14, 2018, 8pm First Congregational Church, Berkeley A rm e ni a n State C h am b e r Ch oir PROGRAM Mesro p Ma s h tots (362– 4 40) ༳ཱུའཱུཪཱི འཻའེཪ ྃཷ I Knee l Be for e Yo u ( A hym n f or Le nt) Grikor N ar e k a tsi ( 9 51–1 0 03) གའཽཷཱཱྀུ The Bird (A hymn for Easter) TheThe Bird BirdBir d (A (A(A hymn hymnhym forn for f oEaster) rEaster) East er ) The Bird (A hymn for Easter) K Kom itas (1869–1 935) ཏཷཱྀཿཡ, ོཷཱྀཿཡ K K K Holy, H oly གའཿོའཱུཤའཱུ ཤཿརཤཿ (ཉའཿ ༳) Rustic Weddin g Son g s (Su it e A , 1899 –1 90 1) ༷ཿཱུཪྀ , རཤཾཱུཪྀ , P Prayer r ayer ཆཤཿཪ ེའཱུ འཫའཫ 7KH%UL The B ri de’s Farewell ༻འརཽཷཿཪ ཱིཤཿ , ལཷཛཱྀོ འཿཪ To the B ride g room ’s Mo th er ༻འརཽཷཿ ཡའཿཷཽ 7KH%ULGH The Bridegroom’s Blessing ཱུ༹ ལཪཥའཱུ , BanterB an te r ༳ཱཻུཤཱི ཤཿཨའཱི ཪཱི ུའཿཧ , D ance ༷ཛཫ, ཤཛཫ Rise Up ! (1899 –190 1 ) གཷཛཽ འཿཤྃ ོའཿཤཛྷཿ ེའཱུ , O Mountain s , Brin g Bree z e (1913 –1 4) ༾ཷཻཷཱྀ རཷཱྀཨའཱུཤཿར Plowing Song of Lor i (1902 –0 6) ༵འཿཷཱཱྀུ Spring Song(190 2for, P oAtheneem by Ho vh annes Hovh anisyan) Song for Athene Song for Athene A John T a ve n er (19 44–2 013) ThreeSongSong forfSacredor AtheneAth Hymnsene A Three Sacred Hymns A Three Sacred Hymns A Three Sacred Hymns A Alfred Schn it tke (1 934–1 998) ThreeThree SacredSacred Hymns H ymn s Богородиц е Д ево, ра д уйся, Hail to th e V irgin M ary Господ и поми луй, Lord, Ha ve Mercy MissaОтч Memoriaе Наш, L ord’s Pra yer MissaK Memoria INTERMISSION MissaK Memoria Missa Memoria K K Lullaby (from T Lullaby (from T Sure on This Shining Night (Poem by James Agee) Lullaby (from T SureLullaby on This(from Shining T Night (Poem by James Agee) R ArmenianLullaby (from Folk TTunes R ArmenianSure on This Folk Shining Tunes Night (Poem by James Agee) Sure on This Shining Night (Poem by James Agee) R Armenian Folk Tunes R Armenian Folk Tunes The Bird (A hymn for Easter) K Song for Athene A Three Sacred Hymns PROGRAM David Haladjian (b. -

Hamlet on the Screen Prof

Scholars International Journal of Linguistics and Literature Abbreviated Key Title: Sch Int J Linguist Lit ISSN 2616-8677 (Print) |ISSN 2617-3468 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: https://saudijournals.com/sijll Review Article Hamlet on the Screen Prof. Essam Fattouh* English Department, Faculty of Arts, University of Alexandria (Egypt) DOI: 10.36348/sijll.2020.v03i04.001 | Received: 20.03.2020 | Accepted: 27.03.2020 | Published: 07.04.2020 *Corresponding author: Prof. Essam Fattouh Abstract The challenge of adapting William Shakespeare‟s Hamlet for the screen has preoccupied cinema from its earliest days. After a survey of the silent Hamlet productions, the paper critically examines Asta Nielsen‟s Hamlet: The Drama of Vengeance by noting how her main character is really a woman. My discussion of the modern productions of Shakespeare begins with a critical discussion of Lawrence Olivier‟s seminal production of 1948. The Russian Hamlet of 1964, directed by Grigori Kozintsev, is shown to combine a psychological interpretation of the hero without disregarding its socio-political context. The action-film genre deployed by Franco Zeffirelli in his 1990 adaptation of the play, through a moving performance by Mel Gibson, is analysed. Kenneth Branagh‟s ambitious and well-financed production of 1996 is shown to be somewhat marred by its excesses. Michael Almereyda‟s attempt to present Shakespeare‟s hero in a contemporary setting is shown to have powerful moments despite its flaws. The paper concludes that Shakespeare‟s masterpiece will continue to fascinate future generations of directors, actors and audiences. Keywords: Shakespeare – Hamlet – silent film – film adaptations – modern productions – Russian – Olivier – Branagh – contemporary setting. -

Hamlet Study Guide Levels Two & Three Wilson Know the Characters: Hamlet – Prince of Denmark Claudius – Hamlet's Uncl

Hamlet Study Guide Levels Two & Three Wilson Know the Characters: Hamlet – Prince of Denmark Claudius – Hamlet’s Uncle; he was recently crowned king of Denmark Gertrude – Queen of Denmark; Hamlet’s mother Polonius – Advisor to the King Ophelia – Hamlet’s love interest; Polonius’ daughter Laertes – Polonius’ son Ophelia’s brother Horatio – Hamlet’s best friend; voice of reason in the play Fortinbras – Prince of Norway; wants to regain land lost by his father Courtiers: Rosencrantz – Noblemen and acquaintances of Hamlet invited to cheer him Guildenstern – up Osric - Cornelius Voltemand – Ambassador charged with going to Norway Officers, Soldiers, and Servants: Francisco – Marcellus – Soldiers who first witness the ghost while on guard Bernardo – Reynaldo – Servant to Polonius Act One, Scene One 1. What is the setting for the play? Denmark; Elsinore Castle 2. What are Bernardo and Francisco doing at the beginning of the play? They are on watch waiting for their replacements. 3. What is going on that makes this necessary? There is a military threat from Norway, in the form of Young Fortinbras. 4. Why is Horatio summoned to the roof of the castle? The want him to witness and/or validate the appearance of the ghost of the dead king. 5. What decision does Horatio make after witnessing what he does? He decides to tell young Hamlet, because he thinks the ghost will speak to him. Act One, Scene Two 6. What has recently happened in Hamlet’s family? His father died and his mother married his uncle. 7. Why is Hamlet being scolded by his uncle? His uncle feels Hamlet has been mourning his father for too long. -

Language, Humour, Character, and Persona in Shakespeare

Language, Humour, Character, and Persona in Shakespeare Arthur Henry King The rst Oxford English Dictionary (hereafter OED)1 use of “character” as “a personality invested with distinctive attributes and qualities by a novelist or dramatist” is in Fielding’s Tom Jones (1749). OED does not list the Theophrastian2 use reected in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century character-sketches, for example Ben Jonson’s play, Every Man Out of His Humour, “the characters of the persons” (1599),3 those in the then current satires, and in translations and collections.4 Another OED entry under character, “personal appearance” (entry 10) correctly interprets Twelfth Night 1.02.51 “outward character”; but that phrase implies “inward character” too, and OED misinterprets Coriolanus 5.04.26 as the outward sense; but “I paint him in the character” refers to this description of Coriolanus (16-28): He no more remembers his mother now than an eight-year-old horse. The tartness of his face sours ripe grapes. When he walks, he moves like an engine, and the ground shrinks before his treading. He is able to pierce a corslet with his eye, talks like a knell, and his hum is a battery. He sits in his state, as a thing made for Alexander. What he bids be done is nish’d with his bidding. He wants nothing of a god but eternity and a heaven to throne in. I paint him in the character. There is no more mercy in him than there is milk in a male tiger. Compare Coriolanus 2.01.46-65, where Menenius sketches an ironical “character” of himself and makes “character” statements about the tribunes: I am known to be a humorous patrician, and one that loves a cup of hot wine with not a drop of allaying Tiber in’t; said to be something imperfect in favoring the rst complaint, hasty and tinder-like upon too trivial motion; one that converses more with the buttock of the night than with the forehead of the morning.