Fundamentals of Gas Measurement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

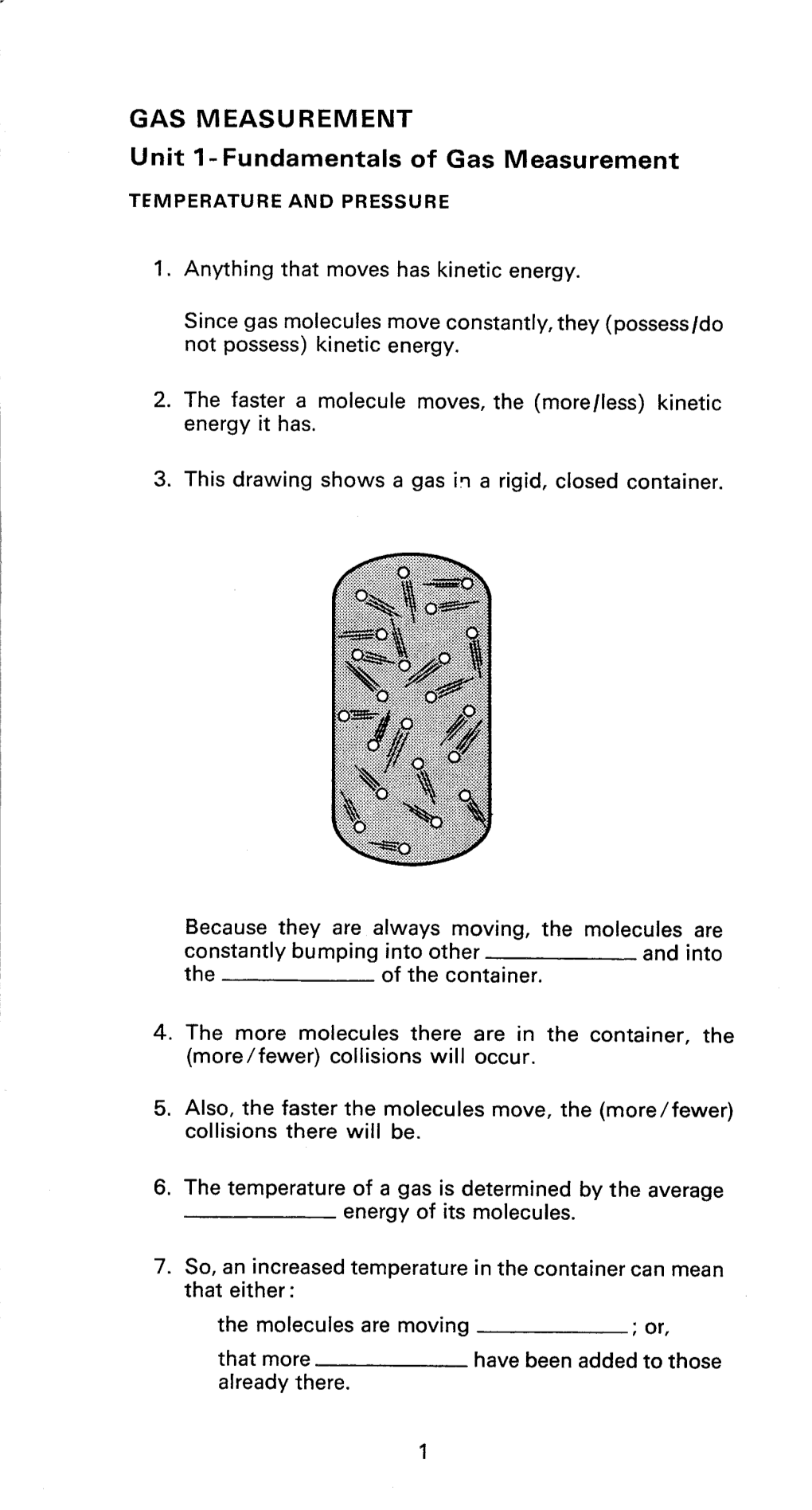

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEKQ7256 Fuel/Fuel Systems

Gas Engines Application and Installation Guide G3600–G3300 ● Fuels ● Fuel Systems LEKQ7256 (Supersedes LEKQ2461) 10-97 G3600–G3300 Fuels Fuel Characteristics Hydrocarbons Standard Condition of a Gas Heat Value Methane Number Air Required for Combustion Common Fuels Natural Gas Sour Gas Propane Propane-Butane Mixtures Propane-Air Propane Fuel Consumption Calculations Digester Gas Sanitary Landfill Gas Manufactured Gases Constituents of Gas by Volume - Percent Producer Gas Illuminating Gas Coke-Oven Gas Blast Furnace Gas Wood Gas Cleaning Fuel Effects on Engine Performance Heat Value of the Air-Fuel Mixture Turbocharged Engines Methane Number Program Calculations Fuel Consumption Detonation Methane Number Compression Ratio Ignition Timing Load Inlet Air Temperature Air-Fuel Ratio Emissions Variations in Heating Value Fuel Temperature Recommendations Fuel Requirements Heating Value Fuels As the number of atoms increases, the molecular weight of the molecule increases and the hydrocarbons are said to become Most of the fuels used in internal combustion heavier. Their physical characteristics change engines today, whether liquid or gaseous, are with each change in molecular structure. composed primarily of hydrocarbons Only the first four of the Paraffin series are (hydrogen and carbon); their source is considered gases at standard conditions of generally petroleum. Natural gas is the most 101.31 kPa (14.696 psia) and 15.55°C (60°F). popular and widely used of the petroleum Several of the others can be easily converted gases. Digester gas (also a hydrocarbon) and to gas by applying a small amount of heat. some manufactured gases (from coal), which contain hydrocarbons, are also used in Standard Condition of a Gas engines with varying degrees of success. -

B. Uniform Regulation for the Method of Sale of Commodities

Handbook 130 – 2019 IV. Uniform Regulations B. Uniform Regulation for the Method of Sale of Commodities B. Uniform Regulation for the Method of Sale of Commodities as adopted by The National Conference on Weights and Measures∗ 1. Background The National Conference on Weights and Measures (NCWM) has long been concerned with the proper units of measurement to be used in the sale of all commodities. This approach has gradually broadened to concerns of standardized package sizes and general identity of particular commodities. Requirements for individual products were at one time made a part of the Weights and Measures Law or were embodied in separate individual Model Regulations. In 1971, this “Model State Method of Sale of Commodities Regulation” was established (renamed in 1983); amendments have been adopted by the Conference almost annually since that time. Sections with “added 1971” dates refer to those sections that were originally incorporated in the Weights and Measures Law or in individual Model Regulations recommended by the NCWM. Subsequent dates reflect the actual amendment or addition dates. The 1979 edition included, for the first time, requirements for items packaged in quantities of the International System of Units (SI), the modernized metric system, as well as continuing to present requirements for U.S. customary quantities. It should be stressed that nothing in this Regulation requires changing to the SI system of measurement. SI values are given for the guidance of those wishing to adopt new SI quantities of the commodities governed by this Regulation. SI means the International System of Units as established in 1960 by the General Conference on Weights and Measures and interpreted or modified for the United States by the Secretary of Commerce. -

Calculation of the Heating Value of a Sample of High Purity Methane for Use As a Reference Material

National Bureau of Standards Reference book not to be Ubrar Admin. Bldg. 1 library, PEC 8 J366 NBS TECHNICAL NOTE 299 Calculation of the Heating Value of a Sample of High Purity Methane for Use as a Reference Material George T. Armstrong /«*** "' °°. 4 o Q 1* US DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Z National Bureau of Standards Q \ T — THE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards 1 provides measurement and technical information services essential to the efficiency and effectiveness of the work of the Nation's scientists and engineers. The Bureau serves also as a focal point in the Federal Government for assuring maximum application of the physical and engineering sciences to the advancement of technology in industry and commerce. To accomplish this mission, the Bureau is organized into three institutes covering broad program areas of research and services: THE INSTITUTE FOR BASIC STANDARDS . provides the central basis within the United States for a complete and consistent system of physical measurements, coordinates that system with the measurement systems of other nations, and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical measurements throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce. This Institute comprises a series of divisions, each serving a classical subject matter area: —Applied Mathematics—Electricity—Metrology—Mechanics —Heat—Atomic Physics—Physical Chemistry—Radiation Physics—Laboratory Astrophysics 2 —Radio Standards Laboratory, 2 which includes Radio Standards Physics and Radio Standards Engineering—Office of Standard Refer- ence Data. THE INSTITUTE FOR MATERIALS RESEARCH . conducts materials research and provides associated materials services including mainly reference materials and data on the properties of ma- terials. -

Heating Values of Natural Gas and Its Components Was Prepared with the Assistance of the Chemical Thermodynamics Data Canter of the National Bureau of Standards

(MBS I A publi- Rer#ence MBSIR 82-240 Heatmg Values of Natural Gas and Its Components U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Bureau of Standards Center for Chemical Physics Chemical Thermodynamics Division Washington, DC 20234 May 1982 Technical Report Issued August 1982 red by e International des Importateurs Gaz natural Liquifie (GIIGNAL) aXTIOBAlf BUHUAU O# enrAJta>AKva tlMBAMT NBSIR 82-2401 AUG 1 9 1982 HEATING VALUES OF NATURAL GAS I C>-_ AND ITS COMPONENTS . Slo e- George T. Armstrong Thomas L. Jobe, Jr. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Bureau of Standards Center for Chemical Physics Chemical Thermodynamics Division Washington, DC 20234 May 1982 Technical Report Issued August 1 982 Sponsored by Groupe International des Importateurs de Gaz Natural Liquifie (GlIGNAL) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, Malcolm Baldrige, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS, Ernest Ambler. Director ( f 'i I i ''i ji ‘ f Preface The Office of Standard Reference Data of the National Bureau of Standards is responsible for a broad-based program to provide reliable physical and chemical reference data to the U.S. technical community. Under this program a number of data evaluation centers both at N3S and at universities and other private institutions are supported and coordinated; these activities are collectively known as the National Standard Reference Data System (NSRDS). Important areas of the physical sciences are covered systematically by NSRDS data centers, and data bases with broad utility are prepared and disseminated. These centers can also take on special compila- tions of data addressing specific applications. The existence of an ongoing program permits the collection of data for these special compilations to be carried out in an efficient and timely manner. -

Properties of Natural Gas

9/29/2014 GAS FIELD ENGINEERING PROPERTIES OF NATURAL GAS 1 CONTENTS - Introduction - Composition of Natural Gas - Ideal Gas Law - Properties of Gaseous Mixtures - Real Gas Equation of State - Determination of Compressibility Factor - Gas Conversion Equations 2 1 9/29/2014 Lesson Learning Outcome At the end of the session, students should be able to: • Explain the governing laws of gas behavior. • Calculate basic parameters for determination of Gas flow performance, volume measurement and Gas reserves . 3 2.1 Introduction • Natural gas is a mixture of hydrocarbon gases and impurities. • Hydrocarbon gases normally found in natural gas are methane, ethane, propane, butanes, pentanes, and small amounts of hexanes, heptanes, octane, and the heavier gases. • The impurities found in natural gas include carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, nitrogen, water vapor, and heavier hydrocarbons. • Usually, the propane and heavier hydrocarbon fractions are removed for additional processing because of their high market value as gasoline-blending stock and chemical-plant raw feedstock. • What usually reaches the transmission line for sale as natural gas is mostly a mixture of methane and ethane with some small percentage of propane. 4 2 9/29/2014 2.1 Introduction • Physical properties of natural gases are important in solving gas well performance, gas production, and gas transmission problems. • The properties of a natural gas may be determined either directly from laboratory tests or predictions from known chemical composition of the gas. • In latter case, the calculations are based on the physical properties of individual components of the gas and on physical laws, often referred to as mixing rules, relating the properties of the components to those of the mixture. -

RATES of HYDROGEN-GRAPHITE REACTION BETWEEN 1550° and 2260° C by Wizzium A

NASA TECHNICAL NOTE RATES OF HYDROGEN-GRAPHITE REACTION BETWEEN 1550° AND 2260° C by WiZZium A. Sunders Lewis Reseurch Center CZeveZund, Ohio NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON, D. C. APRIL 1965 TECH LIBRARY KAFB, NM IIlllll HIlllll lllll lllll IIll1 Ill1 0077711I RATES OF HYDROGEN-GRAPHITE REACTION BETWEEN 1550' AND 2260' C By William A. Sanders Lewis Research Center Cleveland, Ohio NATIONAL AERONAUT ICs AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION For sole by the Office of Technicol Services, Deportment of Commerce, Woshington, D.C. 20230 -- Price $1.00 I- l1l1l1llll1l I I I ll ll I I .RATES OF HYDROGEN-GRAPHITE REACTION BETWEEN 1550° AND 2260° C by William A. Sanders Lewis Research Center SUMMARY The rates of reaction of a pitch-free, petroleum coke-base graphite with purified hydrogen were determined in the temperature range 1550° to 2260' C. Experimental weight losses agree very well above 1800' C with calculations based on thermodynamic data for the hydrogen-graphite theoretical equilibrium compositions, where acetylene is calculated to be the major reaction product. Although the experimental curve and the theoretical curve diverge below 1800' C, equilibrium might be achieved at temperatures below 1800° C if slower hydrogen flow rates were employed. IIWRODUCTION Past experimental investigations of the thermal equilibrium between hydro- gen and carbon agree reasonably well with the results obtained by calculation to about 1000° C (ref. 1) and indicate that methane (CH4) is essentially the sole reaction product, the equilibrium concentration of CH4 decreasing with increasing temperature. One investigator, however, reports a minimum methane concentration at 1450' C followed by an increase in methane concentration with increase in temperature to 2000' C (ref. -

Thermodynamic Data for Biomass Conversion and Waste Incineration

/SP-271-2839 Notice This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any informa- tion, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Govetn- ment or any agency thereof. Acknowledgments This document was prepared for the Solar Technical Information Program, US. Depatt- ment of Energy, by Eugene S. Domalski and Thomas L. fobe, Jr. of the Chemical Ther- modynamics Data Center, Chemical Thermodynamics Division, Center for Chemical Physics, and the Office of Standard Reference Data, National Bureau of Standards, Gaithersburg, Md; with assistance from Thomas A. Milne of SERI. It is based on Thermo- dynamic Data of Waste Incineration, NBSIR 78-1479, August 1978, prepared for the American Society for Mechanical Engineers, Research Committee on Industrial and Municipal Wastes, United Engineering Center, New York, and also available as a separate hard-cover publication with the same title from the American Society for Mechanical Engineers. Sarah Sprague is the Information Program Coordinator for the Biofuels and Municipal Waste Technology Division, U.S. -

Analyzing Natural Gas Composition

Analyzing Natural Gas Composition Course No: P02-005 Credit: 2 PDH James R. Weaver, P.E. Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07677 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] Analyzing Natural Gas Composition Introduction The purpose of this course is to educate one on the use of gas composition data to determine properties of hydrocarbon gases that are useful in calculations under static and dynamic conditions. Due to the peculiar interactions of hydrocarbon molecules, an analysis of the gas is needed to determine the specific gravity, critical pressure, critical temperature, heating value, and natural gas liquid content of the gas. Knowing these properties is necessary to determine the deviation from the Ideal Gas Law, flow characteristics of the gas, potential processing requirements of the natural gas, and revenue derived from sale of natural gas and natural gas liquids. Understanding how to calculate and use these natural gas properties is crucial to reservoir, production, and natural gas process engineering. The contents of this course are as follows: • Ideal Gas Law • What is natural gas • Components of natural gas • Properties of natural gas components • Calculation of natural gas properties from gas composition • Conclusions The Ideal Gas Law In order to understand gas properties, one must understand how gases behave. Gas molecules, unlike the other phases of matter – liquids and solids, are not bound together by intermolecular and viscous forces. As such, gases completely fill whatever container in which they reside. This property is very important and can be used to determine how gases behave under the effects of pressure, temperature, and volume. -

The SI Metric Systeld of Units and SPE METRIC STANDARD

The SI Metric SystelD of Units and SPE METRIC STANDARD Society of Petroleum Engineers The SI Metric System of Units and SPE METRIC STANDARD Society of Petroleum Engineers Adopted for use as a voluntary standard by the SPE Board of Directors, June 1982. Contents Preface . ..... .... ......,. ............. .. .... ........ ... .. ... 2 Part 1: SI - The International System of Units . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... 2 Introduction. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 SI Units and Unit Symbols. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 Application of the Metric System. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 Rules for Conversion and Rounding. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 Special Terms and Quantities Involving Mass and Amount of Substance. .. 7 Mental Guides for Using Metric Units. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 Appendix A (Terminology).. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 Appendix B (SI Units). .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 9 Appendix C (Style Guide for Metric Usage) ............ ...... ..... .......... 11 Appendix D (General Conversion Factors) ................... ... ........ .. 14 Appendix E (Tables 1.8 and 1.9) ......................................... 20 Part 2: Discussion of Metric Unit Standards. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 21 Introduction.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 21 Review of Selected Units. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 22 Unit Standards Under Discussion ......................................... 24 Notes for Table 2.2 .................................................... 25 Notes for Table 2.3 ................................................... -

Manual of Petroleum Measurement Standards Chapter 15—Guidelines for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) in the Petroleum and Allied Industries

Manual of Petroleum Measurement Standards Chapter 15—Guidelines for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) in the Petroleum and Allied Industries FORMERLY API PUBLICATION 2564 FOURTH EDITION, XXXXXX This document is not an API Standard; it is under consideration within an API technical committee but has not received all approvals required to become an API Standard. It shall not be reproduced or circulated or quoted, in whole or in part, outside of API committee activities except with the approval of the Chairman of the committee having jurisdiction. Copyright API. All rights reserved 2 API MANUAL OF PETROLEUM MEASUREMENT STANDARDS Introduction The general purpose of this publication is to encourage and facilitate uniformity of metric practice within the petroleum industry. The specific purposes are as follows: 1. To define metric practice for the petroleum industry; 2. To encourage uniformity of metric practice and nomenclature within the petroleum industry and 3. To facilitate the use of SI in all aspects of the petroleum industry. Use of this publication by the American Petroleum Institute, its divisions, and its members implements API’s policy and also implements recommendations in ISO 1000—1992, SI Units and Recommendations for the Use of Their Multiples and of Certain Other Units [I]1. Production of the first edition of API’s Publication 2564 in 1973 was encouraged by API member companies either operating internationally or participating in the activities of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). The Institute of Petroleum, Great Britain, (IP) and the Canadian Petroleum Association (CPA) both offered their full endorsement and accompanied it with valuable technical support and assistance. -

Natural Gas Gathering

Natural Gas Gathering Course No: R04-002 Credit: 4 PDH Jim Piter, P.E. Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 9 Greyridge Farm Court Stony Point, NY 10980 P: (877) 322-5800 F: (877) 322-4774 [email protected] NATURAL GAS GATHERING 1. INTRODUCTION This course provides guidance on the process of natural gas gathering. Basic physic laws, constants and formulas are provided at the beginning of this course to get a better understanding of their applications in the example problems illustrated later in the course. Several discussion points are introduced and illustrated further through the example calculations provided. While some of the values and formulas used may be familiar to those who more advanced in the topic being presented; they may serve as a refresher or a reference to others. Many of these values and formulas depend on using charted curves which in most cases were developed from equations (provided below) intended to be adapted into software programs. 2. PHYSIC LAWS Avogadro Law: The number of moles is the same for all gas existing at the same pressure, volume and temperature. This shows that ideal gas represents a state of matter. When an actual gas is lowered towards zero pressure, the relationship PV = moles x RT holds true. If the pressure of an actual gas is lowered towards zero pressure, the temperature will converge to the same fixed value. __ From this a universal gas constant (R) was developed. Boyles Law: If the temperature of a fixed mass of gas is held constant and the volume of the gas is varied, the pressure exerted by the gas varies in a relation such that the pressure x volume remains essentially constant (absolute pressure x volume = constant). -

FUNDAMENTALS of NATURAL GAS CHEMISTRY Steve Whitman Coastal Flow Measurement, Inc

FUNDAMENTALS OF NATURAL GAS CHEMISTRY Steve Whitman Coastal Flow Measurement, Inc. In order to understand the chemistry of natural gas, it is volume a solid occupies does not vary much with important to be familiar with some basic concepts of changes in temperature and pressure. In liquids, the general chemistry. Here are some definitions you should individual particles are confined to a given volume. A know: liquid flows and assumes the shape of its container. Liquids cannot be easily compressed. Gases are much Matter — anything that has mass and occupies space. less dense than liquids and solids. They occupy all parts of any vessel in which they are confined. Gases are Energy — the capacity to do work or transfer heat. capable of infinite expansion and are easily compressed. They consist primarily of empty space because the Elements — substances that cannot be decomposed individual particles are so far apart. into simpler substances by chemical changes. There are approximately 112 known elements. Examples: UNITS OF MEASUREMENT carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen. Quantities of matter can be expressed in a variety of Atom — the smallest unit in which an element can exist. ways depending on the nature of the substance being Atoms are composed of electrons, protons, and measured. For example, solids are generally measured neutrons. by weight while liquids are measured by volume or weight. Gas is most commonly measured in units of Compounds — pure substances consisting of two or volume but can also be measured by weight. The more different elements in a fixed ratio. Examples: standard unit of volume used in natural gas measurement water and methane.