Fiction | 'The Crow-Flight of the New York Times' by Prabhakar Singh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Ground Water Year Book, Bihar (2015 - 2016)

का셍ााल셍 उप셍ोग हेतू For Official Use GOVT. OF INDIA जल ल MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD जल ,, (2015-2016) GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) म鵍य पूर्वी क्षेत्र, पटना सितंबर 2016 MID-EASTERN REGION, PATNA September 2016 ` GOVT. OF INDIA जल ल MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES जल CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD ,, (2015-2016) GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) म鵍य पर्वू ी क्षेत्र, पटना MID-EASTERN REGION, PATNA सितंबर 2016 September 2016 GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) CONTENTS CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables i List of Figures ii List of Annexures ii List of Contributors iii Abstract iv 1. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................1 2. HYDROGEOLOGY..........................................................................................................1 3. GROUND WATER SCENARIO......................................................................................4 3.1 DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL........................................................................................8 3.1.1 MAY 2015.....................................................................................................................8 3.1.2 AUGUST 2015..............................................................................................................10 3.1.3 NOVEMBER 2015........................................................................................................12 3.1.4 JANUARY 2016...........................................................................................................14 -

Academic Programmes and Admissions 5 – 9

43rd ANNUAL REPORT 1 April, 2012 – 31 March, 2013 PART – II JAWAHARLAL NEHRU UNIVERSITY NEW DELHI www.jnu.ac.in CONTENTS THE LEGEND 1 – 4 ACADEMIC PROGRAMMES AND ADMISSIONS 5 – 9 UNIVERSITY BODIES 10 – 18 SCHOOLS AND CENTRES 19 – 297 ● School of Arts and Aesthetics (SA&A) 19 – 29 ● School of Biotechnology (SBT) 31 – 34 ● School of Computational and Integrative Sciences (SCIS) 35 – 38 ● School of Computer & Systems Sciences (SC&SS) 39 – 43 ● School of Environmental Sciences (SES) 45 – 52 ● School of International Studies (SIS) 53 – 105 ● School of Language, Literature & Culture Studies (SLL&CS) 107 – 136 ● School of Life Sciences (SLS) 137 – 152 ● School of Physical Sciences (SPS) 153 – 156 ● School of Social Sciences (SSS) 157 – 273 ● Centre for the Study of Law & Governance (CSLG) 275 – 281 ● Special Centre for Molecular Medicine (SCMM) 283 – 287 ● Special Centre for Sanskrit Studies (SCSS) 289 – 297 ACADEMIC STAFF COLLEGE 299 – 304 STUDENT’S ACTIVITIES 305 – 313 ENSURING EQUALITY 314 – 322 LINGUISTIC EMPOWERMENT CELL 323 – 325 UNIVERSITY ADMINISTRATION 327 – 329 CAMPUS DEVELOPMENT 330 UNIVERSITY FINANCE 331 – 332 OTHER ACTIVITIES 333 – 341 ● Gender Sensitisation Committee Against Sexual Harassment 333 ● Alumni Affairs 334 ● Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Advanced Studies 335 – 337 ● International Collaborations 338 – 339 ● Institutional Ethics Review Board Research on Human Subjects 340 – 341 JNU Annual Report 2012-13 iii CENTRAL FACILITIES 342 – 358 ● University Library 342 – 349 ● University Science Instrumentation Centre 349 – 350 -

1-5 GEN PROVISIONAL MERIT LIST.Xlsx

PRAKHAND TEACHER NIYOJAN 2019 PRAKHAND-BARSOI (KATIHAR) SUBJECT- GENERAL (1-5) PROVISIONAL MERIT LIST (ALL CATEGORY) TOTAL POST = 14 (UR-0, URF-0, EWS-2, EWSF-3, EBC-1, EBCF-1, SC-1, SCF-2, ST-1, STF-0, BC-1, BCF-0, R/F-2) QUALIFICATION % FATHER'S CANDIDATE DATE OF S APPLY DATE /HUSBAND' ADDRESS E TET TET TYPE NAME BIRTH YEAR SL.NO. % TOTAL % GENDER PASSING G % APP.NO. S NAME TETTYPE WEITAGE REMARKS TRAINING TRAINING NAME OF INTER PERCENTAG RESERVATIO MERITMARK MATRIC INSTITUTION N CATEGORYN TRAININ MERITPOINT 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 SHAIK SHAIK SREE LAKSHMI MACHHAIL 1 201 10-10-2019 DARAKSHA MOHAMM 24-07-98 93.00 92.6 81.2 88.93 62 2 90.93 VENKATESWAR UR BARSOI KATIHAR 2018 APTET DELED NOORI AD FEMALE A DED AZEEZUR ABHAY N W T T RAVEENA COLLEGE 2 309 22/10/19 SHANAKR 19/09/97 NALANDA SC 95.00 70.80 82.69 82.83 70.60 4 86.83 B.ED CTET KUMARI 2019 PRASAD FEMALE DEOGHAR BIHAR SHARIF ANUSHIKHA BINDESHW 3 N151 13/7/20 22/10/97 BANKA 68.60 89.2 84.43 80.74 72 4 84.74 N I O S EBC CTET SAHA ARI SAHA 2019 D.EL.ED FEMALE SHWETA 4 216 BY POST BHOLA SAH 26-08-1995 ARARIA 91.20 77.4 74.23 80.94 66.66 2 82.94 EBC B.ED CTET KUMARI 2019 FEMALE BOULIA MD SAFIQUE MD ZARISH MANUU CTE 5 91 30-09-2019 07-02-95 MANIHARI 75.60 72 83 76.87 80.6 6 82.87 EBC BED CTET 2019 ALAM ALAM MALE ASANSOL KATIHAR MD SUKHDEV MANSOOR BIGHOUR HAT SINGH LAVKUSH 6 297 21-10-2019 ASHIQUE 20-11-98 BC 95.00 72.2 74 80.4 66 2 82.40 CTET 2019 ALAM BARSOI KATIHAR MALE ELAHI DELED DEGREE COLLEGE BHUWANW MAHILA ARJUN SHASTRI NAGAR PRIMARY 7 47 26-09-2019 SHWAR 16-04-93 SC 92.00 72.4 76.06 80.15 60.56 2 82.15 BTET 2017 KUMAR ROY SONAILI KATIHAR MALE ROY DELED TECHER TRAINING QUALIFICATION % FATHER'S CANDIDATE DATE OF S APPLY DATE /HUSBAND' ADDRESS E TET TET TYPE NAME BIRTH YEAR SL.NO. -

Town Survey Report Forbesganj, Series-4, Bihar

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES-4 BIHAR Part-X B TOWN SURVEY REPORT FORBESGANJ Draft by: Edited by: Supervised by ~. P. N. SINHA S. C. SAXENA V.K.BHARGAVA Assistant Director Deputy Director Deputy Director of Census Operations, Bihar of Census Operations, Bihar of Census Operations, Bihar CONTENTS Page Foreword ... (v) Preface (vii) Chapter I Introduction 1-5 Chapter II History of growth of the town 7-8 Chapter III Amenities and services-History of growth and present position 9-17 Chapter IV Economic life of the town 19-42 Chapter V Ethnic and selected socio-demographic characteristics of the population 43-63 Chapter VI Migration and settlement of families 64-75 Chapter VII Neighbourhood pattern 76-86 Chapter VIII Family life in the town 87-93 Chapter IX Housing and materia I culture 95-102 Chapter X Organisation of power and prestige 103-106 Chapter XI Leisure and recreation, social participation, social awareness, religion and crime. 107-112 Chapter XII Linkage and Continua 113-126 Chapter XIII Conclusion 127-128 Map & Charts Showing Urban Land use Showing Pre-urban area Showing Public utility services FORBESGANJ TOWN URBAN LAND USE (NOT TO SCALE) N i BOUNDARY> TOWN WNlD ROAD Rs ,., RAILWAY .. BUSINESS A~EA re-.-el I!.!..!.!I ADMINISTAATIVE AREA ~ RESIDENTIAL AREA • EDUCATIONAL AREA ~ INDUSTRIAL AREA D AGRICULTURAL AREA D UNCLASSIFIED AREA I REGISTRY OFFICE VETERINARY 2 POST OfFICE POLICE STATION 1 HOSPITAL 6 INSPECTION BUNGALOW ~ GRAVE YARD FORBESGANJ TOWN PERI· URBAN AREA Furlongs 8 4 (0 1 Miles t:::t;:!:~~~=::::::l Km, I o 1 Kms. / \ \ ,.1 __ ._ ........ -

Download Download

eTropic: electronic journal of studies in the tropics Impacts of Historical Pandemics on India: Through the Lens of 20th Century Hindi Literature Prachi Priyanka https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9642-8068 Sharda University, Uttar Pradesh, India Abstract India has been swept by pandemics of plague, influenza, smallpox, cholera and other diseases. The scale and impact of these events was often cataclysmic and writers offered a glimpse into the everyday life of ordinary people who lost their lives and livelihoods and suffered the angst and trauma of mental, physical and emotional loss. This paper focuses on the devastation caused by pandemics especially in the Ganges deltaic plains of India. Through selected texts of 20th century Hindi writers – Munshi Premchand, Phanishwar Nath Renu, Suryakant Tripathi Nirala, Bhagwan Das, Harishankar Parsai, Pandey Bechan Sharma – this paper aims to bring forth the suffering and struggles against violence, social injustices and public health crises in India during waves of epidemics and pandemics when millions died as they tried to combat the rampant diseases. Keywords: historical pandemics, 20th century Hindi Literature, pandemic literature, epidemics in India, cholera, smallpox, plague, influenza . eTropic: electronic journal of studies in the tropics publishes new research from arts, humanities, social sciences and allied fields on the variety and interrelatedness of nature, culture, and society in the tropics. Published by James Cook University, a leading research institution on critical issues facing the world’s Tropics. Free open access, Scopus Listed, Scimago Q2. Indexed in: Google Scholar, DOAJ, Crossref, Ulrich's, SHERPA/RoMEO, Pandora. ISSN 1448-2940. Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 free to download, save and reproduce. -

MARCH 2017 .Com/Civilsocietyonline `50

VOL. 14 NO. 5 MARCH 2017 www.civilsocietyonline.com .com/civilsocietyonline `50 SCHOOL IN THE SKY AN EDUCATION INITIATIVE REACHES FORGOTTEN CORNERS OF ODISHA MLA ORGANISES JOB MELA INTERVIEW THINK TANK FUNDING Pages 8-9 ‘disabled people Pages 25-26 KATHPUTLI SHIFT BEGINS NOW WORK IN THE BHAGALPUR AND AFTER Pages 10-11 BEST COMPanies’ Pages 29-30 THE SHARED WORKSPACE JAVED ABIDI AYURVEDA ADVISORY Pages 22-23 Pages 6-7 Page 34 CONTENTS R E A D U S. W E R E A D Y O U. The learning deficit CHOOLING isn’t just about having schools, whether government or private. So, though we have schools, a learning deficit casts its long shadow over us. This is because teachers are not teaching and children Sare either dropping out or just getting by. As a result, millions and millions of young people won’t be employable except in menial jobs. Better quality education delivered on a scale that suits the size of the country is the way out. Only the government has the resources to do it. The 1,000 Schools Project by Tata Steel and the NGO, Aspire, in three COVER STORY districts of Odisha is an interesting initiative by a private player to strengthen the government system. It deals with many complex issues like enthusing School in the sky teachers, empowering communities and improving pedagogy. It draws on Tata Steel and Aspire have come together to improve the information technology to speed things up and address diversity. functioning of 1,000 government schools in Odisha by raising Transforming education in India requires being in mission mode. -

Forbesganj D/C Line to Araria GSS ( Route Length- 04 Rs

BIHAR STATE POWER TRANSMISSION CO. LTD. PATNA (Regd. Office – Vidyut Bhawan, Bailey Road, Patna) (Contact No– 0612-2504655, M No- 7763817705, Fax No– 0612-2504655, Email ID – [email protected]) (TIN VAT No – 1011257007, TIN CST No – 10011146136, CIN – U40102BR2012SGC018889) (Department of P&P of BSPTCL) Tender Notice for (NIT) No.- 08/PR/BSPTCL/2015 Online tenders are invited by Chief Engineer (Transmission) for the followings:- Description of work Estimated EMD Cost of B.O.Q. (Rs.) Completion Cost (Rs.) (Rs.) Period 1. Construction of 132 KV LILO line on 132 KV Kishanganj- Forbesganj D/C Line to Araria GSS ( Route Length- 04 Rs. 10,000.00 to BSPTCL in 12 Months CKM ) form of DD and Rs. from LOI. 32.40 Cr. 37.40 Lakh 16,854.00 to be paid online 2. Construction of 132 KV LILO line on 132 KV Purnea- for Bid Processing Fee. Saharsa line to Chikni, Dhamdaha GSS (Route Length- 0.5 CKM ) Receipt of Tender up to 15:00 Hrs. on 09 .03.2015 3. Construction of 132 KV LILO line on 132 KV Dalkola- Date of opening at 15:00 Hrs. on 10 .03.2015 kishanganj S/C line to Baisi(Dalkola) GSS (Route Length- 0.2 CKM ) 4. Construction of 132 KV 132 KV Kishanganj(new)-Barsoi DCSS line to Barsoi GSS (Route Length : 70 CKM) Eligibility Criteria Tender documents, etc are available in downloadable from at websites http://www.eproc.bihar.gov.in Downloaded tender documents must be accompanied with Demand Draft in favor of “Accounts officer, BSPTCL, payable at Patna towards the cost of BOQ failing which the tender shall be summarily rejected (Original Demand Draft to be submitted to BSPTCL, Vidyut Bhawan Patna by 09 /03/2015 positively). -

December 2017

EDITOR Estd. 1997 ISSN 0972-0901 Dr. Chhote Lal Khatri University Professor, Department of English T.P.S. College, Patna EXECUTIVE EDITOR Dr. Kumar Chandradeep CYBER University Professor P.G. Department of English, College of Commerce, Arts & LITERATURE Science, Patna A BI-ANNUAL JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES E-mail: [email protected] Approved by U.G.C. Sl. No.-01 Journal No.-46482 Dr. Rajendraprasad Y. Shinde Impact Factor- 5.050 Associate Professor of English Kisan Veer Mahavidyalaya, (vol. xx (Issue 40), No.-II, December, 2017) Wai, Satara- 412803 EDITORIAL ADVISORS Dr. Ravindra Rajhans Padma Shri Dr. Shaileshwar Sati Prasad Dr. J. P. Singh PEER REVIEWED Dr. R. N. Rai REFEREED RESEARCH Dr. Shiv Jatan Thakur JOURNAL Dr. Stephen Gill Dr. Basavaraj Naikar OFFICIAL REVIEWERS Dr. Ram Bhagwan Singh 1 A/4, New Patliputra Colony, Patna- 800013, BIHAR Dr. Sudhir K. Arora Dept. of English Maharaja Harishchandra P. G. College Moradabad, (U.P.) India. Dr. Binod Mishra CYBER PUBLICATION HOUSE Dept. of Humanities CHHOTE LAL KHATRI LIT Rookee - 247667 “Anandmath” mishra. [email protected] Harnichak, Anisabad, Patna-800002 Bihar (India) Dr. K. K. Pattanayak Mob. : 09934415964 Bhagya Residency, Room No.-6, E-mail : [email protected] Ambica Nagar, Bijipur, www.cyberliterature.in Berhampur- 3, Ganjam, www.englishcyber-literature.net Odisha - 760001 khatristoriesandpoetry.blogspot.com Cyber Literature, Vol. XX (Issue 40), No.-II, December, 2017 1 CONTENTS CRITICISM POETRY Editorial .........................../3 1. Sunworship 1. The Pangs of Being Dalit : A — Amarendra Kumar/90 Study of Omprakash Valmiki’s 2. Life Divine Joothan — Pashupati Jha/91 — Dr. P.K. Singh/7 3. -

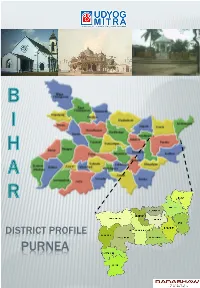

Purnea Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE PURNEA INTRODUCTION Purnea district is one of the thirty-eight administrative districts of Bihar state. Purnea district is a part of Purnea division. Purnea is bounded by the districts of Araria, Katihar, Bhagalpur, Kishanganj, Madhepura and Saharsa and district of West Dinajpur of West Bengal. The major rivers flowing through Purnea are Kosi, Mahananda, Suwara Kali, Koli and Panar. Purnea district extends northwards from river Ganges. Purnia has seen three districts partitioned off from its territory: Katihar in 1976, and Araria and Kishanganj in 1990. Purnea with its highest rainfall in Bihar and its moderate climate has earned the soubriquet of 'Poor's man's Darjeeling’. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Purnea has a rich history and a glorious past. It is believed that the name Purnea originates either from the Goddess Puran Devi (Kali) or from Purain meaning Lotus. The earliest inhabitants of Purnea were Anas and Pundras. In the epics, the Anas are grouped with the Bengal tribes and were the eastern most tribes known to the Aryans during the period of Atharva Samhita while the Pundras, although they had Aryan blood were regarded as degraded class of people in the Aitarya Brahmana, Mahabharata and Manu Samhita, because they neglected the performance of sacred rites. According to the legend of Mahabharata, Biratnagar which gave shelter to the five Pandava brothers during their one year incognito exile, is said to be located in Purnea. During the Mughal rule, Purnea was a military frontier province under the command of a Faujdar. The revenue from this outlying province was spent on the maintenance of troops for protecting the borders against tribes from the north and east. -

National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language Ministry of Human

National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of Higher Education, Government of India Farogh-e-Urdu Bhawan, FC-33/9, Institutional Area Jasola, New Delhi-110 025 SANCTION ORDER Consequent upon the recommendations of the Grant-In-Aid Committee in its meeting held on 24th August 2016 sanction is accorded to the Grant-in-Aid of Rs. 3,71,75,642/- (Rs. Three Crore Seventy One Lakhs Seventy Five Thousand Six Hundred Forty Two only) in favour of the following NGOs/ Organizations/Authors (amount indicated against each), for undertaking select Urdu Promotional activities for the current financial year 2016-2017. Proposals for Seminar/Conference/Workshop/Mushaira S. Name & Address of the NGO/VO/ Topic Sanctioned No Institutions Amount (in Rs) Bihar 1. Mr. Md. Izhar Hussain State Level 60,000/- Secretary Seminar Naaz Commercial Institute Hazrat Ameer Khusro ki Shakhsiyat At-Makhdumpur, Near Masjid, aur Unke Adabi Khidmaat صضـت اهیـ عنـّ کی ىغَیت اؿّ اى کی Dist. Jehanabad-804422, Bihar اػثی عؼهبت 9097351490 [email protected] 2. Mr. Md. Shah Alam National Level 1,25,000/- Secretary Seminar Maulana Waizul Haque Educational Urdu Fiction aur Qaumi Yakjehti اػؿّ فکيي اؿّ لْهی یکزہتی Trust At-Qazi Chak, P.O. Kurnowl, Muzaffarpur-843125, Bihar 9835896866 [email protected] 3. Ms. Farhat Jahan State Level 50,000/- Secretary Seminar Jan Kalyani Allama Iqbal ki Adabi Khidmaat ػﻻهہ الجبل کی اػثی عؼهبت House of Sri Chhote Lal Singh, Behind of Cooperative Bank Hisua, Post Hisua, Dist. Nawada, Bihar 9525414633, 8298517671 4. Ms. Rukhsana International Level 2,00,000/- Secretary Women Mushaira Aasra Bodhgaya Chhatta Masjid, Bari Road, Gaya-823001, Bihar 9835429989, [email protected] 5. -

At Forbesganj Airfield

TENDER FOR AGRICULTURAL RIGHTS PLOT- “B” AT FORBESGANJ AIRFIELD. Name, Designation and Signature of the tender issuing authority: SK Singh, MGR (Comml) JPNI Airport, Patna, Bihar. COST OF DOCUMENTS-1000/- FOR EACH CONTRACT (INCLUSIVE ALL TAXES/LEVIES TAX), Non refundable. TENDER DOCUMENT NO ____________________ Subject: - Tender for Agricultural Rights Plot – “B” at Forbesganj Airfield. 1. Notice Inviting Tenders - 2Sheets 2. General Information & Guidelines - 2Sheets 3. Form of Tender - 2Sheets 4. Licence Agreement - 5Sheets 5. Schedule of premises - 1Sheet 6. General Terms & Condition - 5Sheets 7. Acceptance letter - 1Sheet 8. Letter of understanding from the. - 1Sheet 9. Form of Bank Guarantee - 2Sheets 10. ENVELOPE ‘A’/ ‘B’/Master ENVELOPE -3Sheets (SIGNATURE OF ISSUING AUTHORITY) Name, Designation and Signature of the tender issuing authority: SK Singh, MGR (Comml) JPNI Airport, Patna, Bihar. NOTICE INVITING TENDERS Tender in the prescribed form duly sealed are hereby invited for granting licence for the following:. Sl. No Name of facility Earnest Money Reserved Cost of Tender with its location. Form (including Deposit (EMD). Licence all taxes/ levies. Fee (MRLF) per year. 1. Agricultural Rights Rs.11400/- Rs. 114000 /- Rs.1000/-(One for Plot- (Eleven Thousand (Per Year)( One Thousand Only) “B”at Forbesganj Four Hundred Lac Fourteen Airfield (17.00 Only) Thousand Only) Acres) (Approx) Per year (Experience: lacaf/kr {ks= esa ,d o"kZ dk vuqHko izek.k i= lacaf/kr ch0Mh0vks0@vapy vf/kdkjh }kjk tkjh fd;s x;s gksa One-year experience in the related field. (Experience Certificate to be issued by concerned BDO/Circle Officer). 1- Exclusive Mango tree and fruit plucking. 2.