Examining Narrative Structure and Cultural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spanish NACH INTERPRET

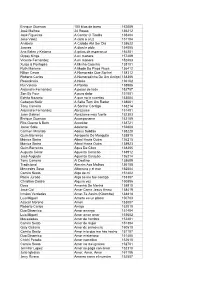

Enrique Guzman 100 kilos de barro 152009 José Malhoa 24 Rosas 136212 José Figueiras A Cantar O Tirolês 138404 Jose Velez A cara o cruz 151104 Anabela A Cidade Até Ser Dia 138622 Juanes A dios le pido 154005 Ana Belen y Ketama A gritos de esperanza 154201 Gypsy Kings A mi manera 157409 Vicente Fernandez A mi manera 152403 Xutos & Pontapés A Minha Casinha 138101 Ruth Marlene A Moda Do Pisca Pisca 136412 Nilton Cesar A Namorada Que Sonhei 138312 Roberto Carlos A Namoradinha De Um Amigo M138306 Resistência A Noite 136102 Rui Veloso A Paixão 138906 Alejandro Fernandez A pesar de todo 152707 Son By Four A puro dolor 151001 Ednita Nazario A que no le cuentas 153004 Cabeças NoAr A Seita Tem Um Radar 138601 Tony Carreira A Sonhar Contigo 138214 Alejandro Fernandez Abrazame 151401 Juan Gabriel Abrazame muy fuerte 152303 Enrique Guzman Acompaname 152109 Rita Guerra & Beto Acreditar 138721 Javier Solis Adelante 152808 Carmen Miranda Adeus Solidão 138220 Quim Barreiros Aeroporto De Mosquito 138510 Mónica Sintra Afinal Havia Outra 136215 Mónica Sintra Afinal Havia Outra 138923 Quim Barreiros Água De Côco 138205 Augusto César Aguenta Coração 138912 José Augusto Aguenta Coração 136214 Tony Carreira Ai Destino 138609 Tradicional Alecrim Aos Molhos 136108 Mercedes Sosa Alfonsina y el mar 152504 Camilo Sesto Algo de mi 151402 Rocio Jurado Algo se me fue contigo 153307 Christian Castro Alguna vez 150806 Doce Amanhã De Manhã 138910 José Cid Amar Como Jesus Amou 138419 Irmãos Verdades Amar-Te Assim (Kizomba) 138818 Luis Miguel Amarte es un placer 150703 Azucar -

Canciones Para Bals De Bodas

Una pequeña parte de ti – Aleks Sintek 2No one cant take you away from me now - Marillion 3Todo Cambio – Camila 4Te amo – Alexander Acha 5Tu de que vas – Franco De vita 6Cielo – Benny Ibarra 7Contigo – Erick Rubín 8Sentirme Vivo – Emmanuel 9No hace falta – Mijares 10Have I told you latley that i love you – Rod Stewart 11A fuego lento – Rossana 12From this moment – Shania Twain 13Eres - Café Tacuba 14Inspiración – Benny Ibarra 15Por amarte - Enrique Iglesias 16La cosa más bella – Eros Ramazotti 17Tres veces amor - Lucero y Mijares 18O tu o ninguna – Luis Miguel 19El poder de tu amor – Ricardo Montaner 20Tu amor, mi amor – Soraya PARTE 2 1. Todo cambió-Camila 2. The way you look tonight-Frank Sinatra 3. Your song-Elthon John 4. Cielo-Benny Ibarra 5. El privilegio de amar-Lucero y Mijares 6. Inspiración-Benny Ibarra 7. Te amo-Alexander Acha 8. Sentirme vivo-Emmanuel 9. A fuego lento-Rossana 10. Desde que llegaste-Reily Parte 3 1. In the Name of Love – Groover Washington 2. The Way You Look Tonight – Frank Sinatra 3. Your Song – Elton John 4. Desafinado – Kenny G 5. Romeo y Julieta – Richard Clayderman 6. La Vie en Rose – Interpretada por Mantovani 7. Being With You – George Benson 8. In a Sentimental Mood – Duke Ellington and John Coltrane 9. Because I Love You – Richard Clayderman 10. Silhouette – Kenny G 11. Hasta Mi Final – IL Divo 12. Heaven – Bryan Adams 13. Por Ti Volaré – Andra Bocelli 14. Moi Laskovyi I Nejnti Zver (Mi Bestia Dulce y Tierno, un melodrama ruso) - Un vals de Eugen Doga 15. -

INSIDE THIS ISSUE Fashion Lion

the Albright College FAshion DepArtment neWsletter • FAll 2011 FASHION LION What’s Hot at Albright? African Textile Design INSIDE THIS ISSUE Designers and Mass Marketing Meet the Faculty: Kendra Meyer, M.F.A. Letter from the Editor EVERYTHI NG by Mary Rose Davis ’15 Dear Readers, Welcome to our first issue of the Fashion OLD Lion! Previously, the fashion newsletter was Incorporating vintage fashion into modern looks is easy. called Seventh on Thirteenth, a play on words that mimicked Seventh on Sixth where “Thanks, it’s vintage,” is possibly one of the coolest things you can say when New York City’s Fashion Week was held receiving a compliment on your outfit. for many years. With the relocation of the With fashion trends from the past becoming more popular, it’s important to fashion week events uptown to the Lincoln know how to incorporate these trends into your style without looking “dated.” Center, we held a contest this semester to come up with a new Once you do, you’ll have a whole new — or old as the case may be — look. name for the newsletter. Congratulations to fashion design and First, you can’t wear it if you don’t own it. So get your fashionable self to the merchandising major Monica Tulay ’12 for the winning entry. closest thrift store or just raid your parents’ closet and find that perfect piece for For me, this change in name serves as a symbol of my years you. One thing to keep in mind is that it’s always easier to start with smaller items at Albright. -

Grazalema : Drama Histrico En Tres Actos Original Y En

J ± i ó -©*>-*-«"0.<-«-0^-0*-<>-0-»-0<-0^-«-<>-0-OK>-^«0-0-^^ EL TEATRO. COLECCIÓN DE OBRAS DRAMÁTICAS ¥ LÍRICAS. GBAZAIJBMA. DRAMA EN VERSO EN TRES ACTOS. ss&ffimssj. Imprenta de José Rodríguez, calle del Factor, nuca. 9 3653, 5 . PINTOS DI VENTA. Madrid i librería de Cuesta, calle ¿Mayor, nútn 2. PROVINCIAS. Albacete. Pérez. Motril. Ballesteros. Alcoy. V. deMartí é hijos Manzanares. Acebedo. Algeciras. Almenara. Mondoñedo Delgado. Alicante. Ibarra. Orense. Robles.; Almería.. Alvarez. Oviedo. Palacio. Áranjuez. Prado. Osuna. Montero. Avila. Rico. Falencia. Gutiérrez é hijos- Orddña. Palma. Gelabert. Barcelona. Viuda de Mayol. Pamplona. Barrena. Bilbao. Astuy. Palma del Rio. Gamero. Hervias. Pontevedra. Cubeiro. Cáceres. Valiente. Puerto de Santa Cádiz. V. de Moraleda. • María. Valderrama. Castrourdiales SaenzFaleeto. Puerto-Rico. Márquez. Córdoba. Lozano. Reus. Prins. Cuenca. Mariana. Ronda. Gutiérrez. Castellón. Gutiérrez. Sanlucar. Esper. Ciudad-Real. Arellano. S. Fernando. Meneses. Coruña. García Alvarez. Sta. Cruz de Te Cartagena. Muñoz Garcia. nerife. Ramirez. Chiclana. Sánchez. Santander. Laparte. Ecija. Garcia. Santiago Escribano. Figueras. Conté Lacoste. Soria. Rioja. Gerona. Doica. Segovia. Alonso. Gijon. Sanz Crespo. S. Sebastian. Garralda. Granada. Zamora. Sevilla. Alvarez y Compv Guadalajara. Oñana. Salamanca. Huebra. Habana. CharlainyFernz. Segorbe. Clavel. Haro. Quintana. Tarragona. Aymat. Huelva. Osorno. Toro. Tejedor. Huesca. Guillen. Toledo. Hernández. Jaén. Idaigo. Teruel. Castillo. Jerez. Bueno. Tuy. Martz. déla Cruz. León. Viuda de Miñón. Talavera. Castro. Lérida» Zara y Suarez. Valencia. Moles. Lugo. Pujol "y Masía. Valladolid. Hernainz. Lorca. Delgado. Vitoria. Galindo. Logroño. Verdejo. VillanuevayGel- Loja. Cano. trú. Magin Beltran y Málaga. Cañavatte. compañía. Matat ó. Abadal. Ubeda. Treviño. Murcia» Hermanos de An- Zamora. Calamita. drion. Zaragoza. V. Andrés. GRAZALEMA. GRAZALEMA, DRAMA HISTÓRICO EN TRES ACTOS ORIGINAL Y EN VERSO DON LUIS DE EGÜILAZ. -

Redalyc.La Telenovela En Mexico

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Directory of Open Access Journals Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Sistema de Información Científica Guillermo Orozco Gómez La telenovela en mexico: ¿de una expresión cultural a un simple producto para la mercadotecnia? Comunicación y Sociedad, núm. 6, julio-diciembre, 2006, pp. 11-35, Universidad de Guadalajara México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=34600602 Comunicación y Sociedad, ISSN (Versión impresa): 0188-252X [email protected] Universidad de Guadalajara México ¿Cómo citar? Fascículo completo Más información del artículo Página de la revista www.redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto La telenovela en mexico: ¿de una expresión cultural a un simple producto para la mercadotecnia?* GUILLERMO OROZCO GÓMEZ** Se enfatizan en este ensayo algunos It is argued in this essay that fictional de los principales cambios que el for- drama in the Tv screen is becoming mato de la ficción televisiva ha ido more and more a simple commodity. sufriendo desde sus orígenes, como If five decades ago, one of the key relato marcado fuertemente por la marks of Mexican Tv drama was its cultura y los modelos de comporta- strong cultural identity, and in fact miento característicos de su lugar y the audience’s self recognition in their su época. En este recorrido se hace plots made them so attractive and referencia a la telenovela “Rebelde” unique as media products, today tele- producida y transmitida por Televisa novelas are central part of mayor mer- en México a partir de 2005. -

Reporte De Telenovelas De Los 80'S 1. COLORINA : Fue Producida En

Reporte de Telenovelas de los 80’s 1. COLORINA : Fue producida en 1980 por Valentín Pimstein considerado uno de los padres de la novela rosa en México, protagonizada por la actriz Lucia Méndez y Enrique Álvarez Félix ; como villanos la telenovela tuvo a José Alonso y a María Teresa Rivas . Contó además con las actuaciones de María Rubio, Julissa y Armando Calvo. Causo impacto en la sociedad al ser la primera telenovela con clasificación C y en ser transmitada a las 23:00 hrs. Además de romper record de llamadas por el concurso convocado para saber quien seria e hijo de colorina. Fue rehecha en 1993 en argentina bajo el titulo de Apasionada. En 2001 por televisa, ahora a mano de Juan Osorio y titulada Salome. Y finalmente fue retransmitida en 2 ocasiones por el canal Tlnovelas siendo la última el 9 de julio del 2012. En marzo del 2011 la revista People en España la considero entre las mejores 20 novelas de la historia. 2. CHISPITA: Fue producida en 1982 producida por Valentin Pimstein, protagonizada adultamente por adultamente por Angélica Aragón y Enrique Lizalde con las participaciones protagonicas infantiles de Lucero y Usi Velasco. En 1983 fue ganadora en los premios TVyNovelas por mejor actriz infantil la actriz Lucero. Lucero actualmente tiene 33 años de carrera artística , a realizado 9 telenovelas , cuanta con mas de 30 premios entre cantante y actriz. Fue remasterizada en 1996 por Televisa bajo el nombre de Luz Clarita. 3. EL DERECHO DE NACER: Está basada en la radio novela cubana, pero en 1981 es transmitida por Televisa baja la producción de Ernesto Alonso y protagonizada por Verónica Castro y Sergio Jiménez, con las participaciones estelares de Humberto Zurita y Erika Buenfil. -

Curriculum Actoral De Kandido Uranga

CURRICULUM ACTORAL DE KANDIDO URANGA Amama Intemperie Listado de producciones al margen de su actividad teatral y de doblaje. 1.- Hil-Kanpaiak (Campanadas a muerto). 2020. Finalización del rodaje. Drama. Dirigida por Imanol Rayo. La historia arranca cuando Fermín, del caserío Garizmendi, descubre una calavera enterrada en su huerto mientras trabaja con la azada. Enseguida le cuenta lo que ha descubierto a Néstor, su hijo, y este, a su vez, le da la noticia a su mujer Berta, arqueóloga de profesión. Pero cuando acuden al prado a sacar el esqueleto, este ha desaparecido misteriosamente. A partir de ahí, hay más muertes y un misterio cada vez más oscuro y profundo. 2.- Diecisiete. (2019). Daniel Sánchez Arévalo. Comedia Héctor es un chico de 17 años que lleva dos interno en un centro de menores. Insociable y poco comunicativo, apenas se relaciona con nadie hasta que se anima a participar en una terapia de reinserción con perros. En ella establece un vínculo indisoluble con un perro, al que llama Oveja. Pero un día el perro es adoptado y Héctor se muestra incapaz de aceptarlo. A pesar de que le quedan menos de dos meses para cumplir su internamiento, decide escaparse para ir a buscarlo. 3.- Intemperie (2019). Benito Zambrano. Drama Un niño que ha escapado de su pueblo escucha los gritos de los hombres que le buscan. Lo que queda ante él es una llanura infinita y árida que deberá atravesar si quiere alejarse definitivamente del infierno del que huye. Ante el acecho de sus perseguidores al servicio del capataz del pueblo, sus pasos se cruzarán con los de un pastor que le ofrece protección y, a partir de ese momento, ya nada será igual para ninguno de los dos. -

Linda Lucero Collection on La Raza Silkscreen Center/La Raza Graphics 1971-1990 CEMA 40

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt396nc691 No online items Guide to the Linda Lucero collection on La Raza Silkscreen Center/La Raza Graphics 1971-1990 CEMA 40 Finding aid prepared by Alexander Hauschild, 2006 UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, California, 93106-9010 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Email: [email protected]; URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections 2006 CEMA 40 1 Title: Linda Lucero collection on La Raza Silkscreen Center/La Raza Graphics Identifier/Call Number: CEMA 40 Contributing Institution: UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 5.0 linear feet(103 silkscreen prints and 558 slides) Date (inclusive): 1971-1990 Abstract: Linda Lucero collection on La Raza Silkscreen Center/La Raza Graphics [1971-1990]. As early as 1970, La Raza Silkscreen/La Raza Graphics Center was producing silkscreen prints by Chicano and Latino artists. The organizers and artists of what was originally called La Raza Silkscreen Center designed and printed posters in a makeshift studio in the back of La Raza Information Center (CEMA 40). Physical location: Del Norte creator: Lucero, Linda Access restrictions The collection is open for research. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the Department of Special Collections, UCSB. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Department of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which also must be obtained. -

Lista De Inscripciones Lista De Inscrições Entry List

LISTA DE INSCRIPCIONES La siguiente información, incluyendo los nombres específicos de las categorías, números de categorías y los números de votación, son confidenciales y propiedad de la Academia Latina de la Grabación. Esta información no podrá ser utilizada, divulgada, publicada o distribuída para ningún propósito. LISTA DE INSCRIÇÕES As sequintes informações, incluindo nomes específicos das categorias, o número de categorias e os números da votação, são confidenciais e direitos autorais pela Academia Latina de Gravação. Estas informações não podem ser utlizadas, divulgadas, publicadas ou distribuídas para qualquer finalidade. ENTRY LIST The following information, including specific category names, category numbers and balloting numbers, is confidential and proprietary information belonging to The Latin Recording Academy. Such information may not be used, disclosed, published or otherwise distributed for any purpose. REGLAS SOBRE LA SOLICITACION DE VOTOS Miembros de La Academia Latina de la Grabación, otros profesionales de la industria, y compañías disqueras no tienen prohibido promocionar sus lanzamientos durante la temporada de voto de los Latin GRAMMY®. Pero, a fin de proteger la integridad del proceso de votación y cuidar la información para ponerse en contacto con los Miembros, es crucial que las siguientes reglas sean entendidas y observadas. • La Academia Latina de la Grabación no divulga la información de contacto de sus Miembros. • Mientras comunicados de prensa y avisos del tipo “para su consideración” no están prohibidos, -

Silvia Navarro Quiere Grabar Con Directores De

10446409 12/30/2004 10:16 p.m. Page 3 CINE | VIERNES 31 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2004 | EL SIGLO DE DURANGO | 3B Silvia Navarro ahora piensa intentar en cine, después del éxito de sus telenovelas. ADMIRACIÓN | RECONOCE LABOR DE LOS MEXICANOS Desea hacer cine Silvia Navarro PERSONAJES quiere grabar Trabajos hechos Una actriz con demasiado talento y que en poco tiempo ha llegado con directores a convertirse en la favorita del público mexicano. de talla internacional; ■ “La heredera “ (2004) “Paloma”/Elena Olivares buscará Telenovela... María Claudia ■ “La calle de las novias” ■ “Desafío de estrellas” (2000) Telenovela... Aura una buena historia (2003) Show Sánchez ■ “La duda” (2002) ■ “Catalina y Sebastián” MÉXICO, DF (NOTIMEX).- La ac- Telenovela... Victoria (1999) Telenovela... Catalina triz mexicana Silvia Navarro ■ “Cuando seas mía” ■ “Perla” (1998) reveló su deseo de incursio- (2001) Telenovela... Teresa Telenovela... Perla/Julieta nar en el cine y enfatizó que FUENTE: Agencias. su sueño es muy alto, pues quiere trabajar con directo- res de talla internacional, co- González Iñárritu y Alfonso fuera de la televisora. mo Pedro Almodóvar, Ale- Cuarón. Refirió que también le en- jandro González Iñárritu y “Admiro a Almodóvar y cantaría incursionar en tea- Alfonso Cuarón. me encantan sus películas, tro, por lo que está en busca En entrevista, la artista pero también reconozco la de una obra en la que pueda comentó que entre sus planes gran labor que han desempa- participar en fecha próxima, para 2005 está buscar una ñado nuestros compatriotas y puntualizó que desea que buena historia cinematográfi- Iñárritu y Cuarón, por lo que sea una comedia, pues “me ca con la que pueda debutar sería un verdadero honor tra- gusta lo ligero y divertido, en la pantalla grande, pues es bajar con ellos”, señaló. -

Vivir Más Y Mejor Los Miércoles, a Las 17:00 H

Nº 310 • ABRIL 2021 • 4 € cableCABLEMEL Nº 310 • ABRIL 2021 • 4 € guia de programación de televisión Vivir más y mejor Los miércoles, a las 17:00 h. en Odisea 9-1-1: Lone Star/ Temporada 2 Estreno: 12 de Abril 22:00 en FOX sumario abril 2021 CINE AMC ................................................................................ 8 Canal Hollywood ..................................................... 10 Sundance......................................................................12 AXN white ....................................................................15 TCM .................................................................................16 TNT ..................................................................................17 De Pelicula ................................................................. 28 ENTRETENIMIENTO AXN White ....................................................................15 Fear the Nurses Crimen e Investigación ......................................... 21 Fox Life ..........................................................................22 Walking Dead Ambientada en Toronto, Nurses 8 22 sigue a cinco jóvenes enfermeras Fox .................................................................................23 T6 que trabajan en la primera línea de un concu- Calle13 ..........................................................................24 Las nuevas aventuras de los protagonistas de rrido hospital del centro, dedicando sus vidas la franquicia ponen de manifiesto lo que es a ayudar a los demás, mientras -

Francisca Content Synopsis Credits Eva López-Sánchez

Francisca (...which side are you on?) Content Synopsis Credits Eva López-Sánchez - Cast Ulrich Noethen - Fabiola Campomanes - Arcelia Ramírez – Julio Bracho - Rafael Martín - directors note www.francisca-movie.com SUR Films 2002 • eMail: [email protected] Francisca (...which side are you on?) Synopsis (The story is set in Mexico between 1971 and 1974) Escaping from his country, Helmut Busch, a former informant for the secret police in East Germany, the Stasi, lands in Mexico under a false identity. His wish is to start a new life far from Europe and where he is less likely to be found. Nevertheless, he is immediately identified by the Mexican secret services lead by Díaz, who with the threat of sending him back to Germany as a deserter coerces him to work for him. Díaz, asks him to infiltrate a group of politically militant students. To achieve this objective, Helmut Busch adopts his new identity as Bruno Müller, a historian and visiting professor in the University of Mexico. He will deliver a series of conferences regarding Paris´May 68 student riots. Bruno´s mission is made difficult when a love affair with Adela, one of the members of the group, starts getting serious. Obliged by the situation and under severe pressure, Bruno does his job trying to maintain as far away from any compromising situation as possible in order to inform nothing important. However, things get complicated and Bruno´s conflict grows when he finds out that the young woman with whom he has fallen in love with is part of one of the politically militant groups that Díaz is interested in.