The Quarrel by the Ships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell

STUDY GUIDE Photo of Mark L. Montgomery, Stephanie Andrea Barron, and Sandra Marquez by joe mazza/brave lux, inc Sponsored by Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell SETTING The action takes place in east-central Greece at the port of Aulis, on the Euripus Strait. The time is approximately 1200 BCE. CHARACTERS Agamemnon father of Iphigenia, husband of Clytemnestra and King of Mycenae Menelaus brother of Agamemnon Clytemnestra mother of Iphigenia, wife of Agamemnon Iphigenia daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra Achilles son of Peleus Chorus women of Chalcis who came to Aulis to see the Greek army Old Man servant of Agamemnon, was given as part of Clytemnestra’s dowry Messenger ABOUT THE PLAY Iphigenia in Aulis is the last existing work of the playwright Euripides. Written between 408 and 406 BCE, the year of Euripides’ death, the play was first produced the following year in a trilogy with The Bacchaeand Alcmaeon in Corinth by his son, Euripides the Younger, and won the first place at the Athenian City Dionysia festival. Agamemnon Costume rendering by Jacqueline Firkins. 2 SYNOPSIS At the start of the play, Agamemnon reveals to the Old Man that his army and warships are stranded in Aulis due to a lack of sailing winds. The winds have died because Agamemnon is being punished by the goddess Artemis, whom he offended. The only way to remedy this situation is for Agamemnon to sacrifice his daughter, Iphigenia, to the goddess Artemis. Agamemnon then admits that he has sent for Iphigenia to be brought to Aulis but he has changed his mind. -

Iliad Teacher Sample

CONTENTS Teaching Guidelines ...................................................4 Appendix Book 1: The Anger of Achilles ...................................6 Genealogies ...............................................................57 Book 2: Before Battle ................................................8 Alternate Names in Homer’s Iliad ..............................58 Book 3: Dueling .........................................................10 The Friends and Foes of Homer’s Iliad ......................59 Book 4: From Truce to War ........................................12 Weaponry and Armor in Homer..................................61 Book 5: Diomed’s Day ...............................................14 Ship Terminology in Homer .......................................63 Book 6: Tides of War .................................................16 Character References in the Iliad ...............................65 Book 7: A Duel, a Truce, a Wall .................................18 Iliad Tests & Keys .....................................................67 Book 8: Zeus Takes Charge ........................................20 Book 9: Agamemnon’s Day ........................................22 Book 10: Spies ...........................................................24 Book 11: The Wounded ..............................................26 Book 12: Breach ........................................................28 Book 13: Tug of War ..................................................30 Book 14: Return to the Fray .......................................32 -

Greek and Roman Mythology and Heroic Legend

G RE E K AN D ROMAN M YTH O LOGY AN D H E R O I C LE GEN D By E D I N P ROFES SOR H . ST U G Translated from th e German and edited b y A M D i . A D TT . L tt LI ONEL B RN E , , TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE S Y a l TUD of Greek religion needs no po ogy , and should This mus v n need no bush . all t feel who ha e looked upo the ns ns and n creatio of the art it i pired . But to purify stre gthen admiration by the higher light of knowledge is no work o f ea se . No truth is more vital than the seemi ng paradox whi c h - declares that Greek myths are not nature myths . The ape - is not further removed from the man than is the nature myth from the religious fancy of the Greeks as we meet them in s Greek is and hi tory . The myth the child of the devout lovely imagi nation o f the noble rac e that dwelt around the e e s n s s u s A ga an. Coar e fa ta ie of br ti h forefathers in their Northern homes softened beneath the southern sun into a pure and u and s godly bea ty, thus gave birth to the divine form of n Hellenic religio . M c an c u s m c an s Comparative ythology tea h uch . It hew how god s are born in the mind o f the savage and moulded c nn into his image . -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

The Truce in Iliad 3 and 4

Building Community Across the Battle- Lines: The Truce in Iliad 3 and 4 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Elmer, David. 2012. Building Community Across the Battle-Lines: The Truce in Iliad 3 and 4. In Maintaining Peace and Interstate Stability in Archaic and Classical Greece, ed. Julia Wilker, 25-48. Mainz: Verlag Antike. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33921641 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Building Community Across the Battle-Lines: The Truce in Iliad 3 and 4 Recent work on interstate relations in early Greece has produced two major revisions of established positions. The first is a welcome reassessment of Bruno Keil’s often-cited characterization of peace as “a contractual interruption of a (natural) state of war.”1 As Victor Alonso has stressed, war was only one possible mode of interaction for early Greek communities, and no more the default than either friendship or the lack of a relationship altogether.2 The second major development is represented by Polly Low’s reconsideration of the widespread assumption that “a strict line can be drawn between domestic and international life”: her work reveals the many ways in which Greek political life blurred the boundaries between intra- and inter-polis relationships.3 From a certain point of view, these two reconfigurations can be seen to be mutually reinforcing. -

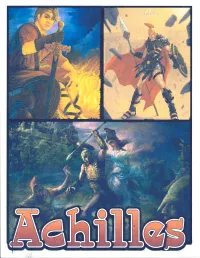

New Achilles Folder.Pdf

ffi ffi Achilles (uh-KlH-leez) was a mighty Greek hero. r. Greeks and Romans told many stories about him. The stories said that Achilles could not be harmed. He was i: ',' , ; \: i ", : : The stories also said that gods helped Achilles and other heroes. During one battle, a hero named Hector threw his spear at Achilles. The goddess Athena (uh-THEE-nuh) knocked the spear down. Then Achilles raised his spear to throw at Hector. But the god Apollo created a fog around Hector. Achilles could not see Hector. Hector ran from Achilles. As Hector ran, Athena approached him. She had i: r i i, ,. , :,: ,'. , herself as one of his brothers. So Hector stopped. Athena offered him a new spear, but it was a trick. When Hector reached for the spear, it disappeared. Achilles then caught up to Hector. He attacked and killed Hector. Achilles defeated many enemies in battle. Achilles' mother was Thetis (THEE-tuhss). She was a sea : ' . Nymphs were creatures that never grew old or died. They w€re : . Achilles' father was the human King Peleus (PEE-1ee-uhss). Peleus ruled an area of Greece called Phthia (THYE-uh). Because Achilles was part human, he would grow old and die. He was : ,, ,, . Thetis wanted to keep Achilles from dying of old age. At night, Thetis put Achilles into a fire to burn off his mortal skin. In the morning, she rubbed ambrosia (am-BRoH-zhuh) on him to heal his body. Ambrosia was the food of the gods. Achilles' mother also wanted to protect her son from harm. -

The Iliad Book 1 Lines 1-487

The Iliad Book 1 lines 1-487. Homer. The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0134:book=1:card=1 [1] The wrath sing, goddess, of Peleus' son, Achilles, that destructive wrath which brought countless woes upon the Achaeans, and sent forth to Hades many valiant souls of heroes, and made them themselves spoil for dogs and every bird; thus the plan of Zeus came to fulfillment, from the time when first they parted in strife Atreus' son, king of men, and brilliant Achilles. [8] Who then of the gods was it that brought these two together to contend? The son of Leto and Zeus; for he in anger against the king roused throughout the host an evil pestilence, and the people began to perish, because upon the priest Chryses the son of Atreus had wrought dishonour. For he had come to the swift ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, bearing ransom past counting; and in his hands he held the wreaths of Apollo who strikes from afar, on a staff of gold; and he implored all the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, the marshallers of the people: Sons of Atreus, and other well-greaved Achaeans, to you may the gods who have homes upon Olympus grant that you sack the city of Priam, and return safe to your homes; but my dear child release to me, and accept the ransom out of reverence for the son of Zeus, Apollo who strikes from afar. -

Iliad and Odyssey - 800-750 BCE Early Greece

Clst 181SK Ancient Greece and the Origins of Western Culture Early Greece A Basic Chronology 1a. Bronze Age Greece - Minoans The Minoan Civilization (1900-1450 BCE) ! ! Knossos, Crete 1b. Bronze Age Greece - Mycenaeans The Mycenaean Civilization (1450-1200 BCE) Mainland Greece, especially the Peloponnesus Mycenae – Palace Megaron Cf. Megaron at Pylos, Palace of Nestor Mycenae – Demons? Mycenae – Palace Megaron Cf. Megaron at Pylos, Palace of Nestor The Bronze Age - Collapse ! Greek Palace structures are destroyed in about 1200-1150 BCE ! Knossos Mycenae Pylos Thebes Tiryns Troy(!) We do not know how or by whom the devastation occurred - the Greeks told a story of invaders (the “Dorian invasion”) 2. The Greek! “Dark Age” - the Iron Age 1200-800 BCE Lefkandi – Heroön plan ! 2. The Iron Age 1200-750 BCE Early Geometric Vase 850 BCE ! 3. The Archaic Period 750-480 BCE 530 BCE 750 BCE 560 BCE 700 BCE 600 BCE Clst 181SK Ancient Greece and the Origins of Western Culture Early Greece A Basic Chronology ! 1a. Bronze Age - Minoans 1900-1450 BCE 1b. Bronze Age - Mycenaeans 1450-1200 2. Iron Age (Dark Ages) 1200-750 3. Archaic Period 750-480 ! “Trojan War” - 1250-1200 BCE Collapse of Bronze Age palace system - 1200-1150 BCE Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey - 800-750 BCE Early Greece “Trojan War” - 1250-1200 BCE Collapse of Bronze Age palace system - 1200-1150 BCE Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey - 800-750 BCE Question: which early Greece does Homer’s Iliad assume? The Bronze Age era of palaces or the Iron Age era sometimes known as the Dark Ages? ! The Trojan War: The Heroes Note: Ilium or Ilias is another name for Troy, thus the Iliad means the story of the war against Troy ! Mycenae (Mycene) Review: Mesopotamia,Phoenicia, Crete, Cyprus, Delphi, Peloponnesus, Ionia Review: Knossos, Mycenae, Pylos Mycenae – aerial view Lion’s gate reconstruction Mycenae – Demons? Mycenae – Palace Megaron Cf. -

The Marriage of Peleus & Thetis

The Marriage of Peleus & Thetis [Groton & May, Chapter 18] Peleus Thetis m. was a mortal man, the son was a sea nymph, one of of Endeis and Aeacus, king the fifty daughters of of Aegina. As a young Nereus, termed Nereids, Achilles man, Peleus and his described by Homer as, brother, Telemon were “silver-footed.” involved in the murder of their half-brother, Phocus. In exile, he married Antigone, then accidentally killed her father, Eurytion. After Antigone killed herself, Peleus again went into exile Portrait of Achilles from a Greek Black-figure vase, c. 530 BC where he met his next wife. The Nuptials The wedding was planned by Zeus (Jupiter) himself and took place on Mt. Pelion. Mortals and immortals alike were invited and all were required to bring gifts. Poseidon (Neptune) gave Peleus a pair of immortal horses, named Balius & Xanthus. The wedding is described by the Greek playwright, Euripides, in “Iphigenia at Aulis” and by the Latin poet, Catullus in poem 64. Discordia [Greek, Ερισ] The goddess of discord and the personification of strife, Discord was the only immortal not invited to the wedding of Peleus and Thetis. Angered, she threw out a golden apple inscribed with the words, “For the Fairest.” Three goddesses, Hera (Juno), Aphrodite (Venus), and Athena (Minerva), immediately begin to quarrel over the apple. Jupiter handed the decision over to the Trojan, Paris, who awards the apple to Aphrodite. Venus in turn offers him the golden apple Helen, wife of Menelaus, King of Sparta. created by Jessica Fisher, 2007 . -

Gaius Iulius Hyginus Fabulae

Filozofická fakulta Masarykovy univerzity v Brně Ústav klasických studií Gaius Iulius Hyginus Fabulae Diplomová práce Autorka: Hana Koudelková Vedoucí diplomové práce: Doc. PhDr. Dagmar Bartoňková, CSc. Brno 2006 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala zcela samostatně a použila pouze uvedené prameny. 2 Děkuji paní doc. PhDr. Dagmar Bartoňkové, CSc. za cenné rady a připomínky při odborném vedení mé diplomové práce. 3 1. Úvod Jako téma své diplomové práce jsem si vybrala po konzultaci s Doc. Bartoňkovou postavu Gaia Iulia Hygina a jeho sbírku nazvanou Fabulae. Již při bližším seznámení se s tématem jsem zjistila, že se budu muset vyrovnat jednak s nedostatkem či nedostupností pramenů, jednak s naprosto rozdílnými názory a přístupy na daný problém u jednotlivých badatelů. Každý filolog, jenž chtěl jakkoliv komentovat Hyginovo dílo, byl do značné míry ovlivněn tím, kterou edici zvolil jako základ pro své bádání. Zcela zásadní překážkou při pátrání po podobě původního Hyginova díla je totiž skutečnost, že originál Hyginova rukopisu se nedochoval, a tudíž nejstarší ucelenou prací zabývající se dílem Fabulae je tzv. editio princeps z pera autora Mycilla. Každá další edice pak do jisté míry měnila náhled na díla předešlá, polemizovala s výsledky bádání či upravovala závěry jejich autorů. Tyto nové „objevy“ pak často přežily pouze do doby, kdy byla zpracována další edice přicházející se závěry novými a ty byly často až v úplném rozporu se závěry předešlých badatelů. Na základě výše uvedených skutečností je tudíž zcela evidentní, že se jednotlivé dosažené výsledky od sebe mohou velmi výrazně lišit, a to jak v závislosti na době, v níž konkrétní autoři a editoři působili, tak i na množství materiálů a počtu edicí, které měli k dispozici. -

People on Both Sides of the Aegean Sea. Did the Achaeans And

BULLETIN OF THE MIDDLE EASTERN CULTURE CENTER IN JAPAN General Editor: H. I. H. Prince Takahito Mikasa Vol. IV 1991 OTTO HARRASSOWITZ • WIESBADEN ESSAYS ON ANCIENT ANATOLIAN AND SYRIAN STUDIES IN THE 2ND AND IST MILLENNIUM B.C. Edited by H. I. H. Prince Takahito Mikasa 1991 OTTO HARRASSOWITZ • WIESBADEN The Bulletin of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan is published by Otto Harrassowitz on behalf of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan. Editorial Board General Editor: H.I.H. Prince Takahito Mikasa Associate Editors: Prof. Tsugio Mikami Prof. Masao Mori Prof. Morio Ohno Assistant Editors: Yukiya Onodera (Northwest Semitic Studies) Mutsuo Kawatoko (Islamic Studies) Sachihiro Omura (Anatolian Studies) Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Essays on Ancient Anatolian and Syrian studies in the 2nd and Ist millennium B.C. / ed. by Prince Takahito Mikasa. - Wiesbaden : Harrassowitz, 1991 (Bulletin of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan ; Vol. 4) ISBN 3-447-03138-7 NE: Mikasa, Takahito <Prinz> [Hrsg.]; Chükintö-bunka-sentä <Tökyö>: Bulletin of the . © 1991 Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden This work, including all of its parts, is protected by Copyright. Any use beyond the limits of Copyright law without the permission of the publisher is forbidden and subject to penalty. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic Systems. Printed on acidfree paper. Manufactured by MZ-Verlagsdruckerei GmbH, 8940 Memmingen Printed in Germany ISSN 0177-1647 CONTENTS PREFACE -

Phoenix in the Iliad

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar Student Research Submissions Spring 5-4-2017 Phoenix in the Iliad Kati M. Justice Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Justice, Kati M., "Phoenix in the Iliad" (2017). Student Research Submissions. 152. https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/152 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PHOENIX IN THE ILIAD An honors paper submitted to the Department of Classics, Philosophy, and Religion of the University of Mary Washington in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors Kati M. Justice May 2017 By signing your name below, you affirm that this work is the complete and final version of your paper submitted in partial fulfillment of a degree from the University of Mary Washington. You affirm the University of Mary Washington honor pledge: "I hereby declare upon my word of honor that I have neither given nor received unauthorized help on this work." Kati Justice 05/04/17 (digital signature) PHOENIX IN THE ILIAD Kati Justice Dr. Angela Pitts CLAS 485 April 24, 2017 2 Abstract This paper analyzes evidence to support the claim that Phoenix is an narratologically central and original Homeric character in the Iliad. Phoenix, the instructor of Achilles, tries to persuade Achilles to protect the ships of Achaeans during his speech. At the end of his speech, Phoenix tells Achilles about the story of Meleager which serves as a warning about waiting too long to fight the Trojans.