Analyzing Manners of Coping Amongst Korean University Students in a Sociocultural Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TUGBOAT Volume 26, Number 2 / 2005 TUG 2005 Conference

TUGBOAT Volume 26, Number 2 / 2005 TUG 2005 Conference Proceedings 106 Conference program, delegates, and sponsors 108 Robin Laakso / Highlights from TUG 2005 110 Conference photos Keynote 111 Wai Wong / Typesetting Chinese: A personal perspective Talks 115 Jonathan Kew / X TE EX, the Multilingual Lion: TEX meets Unicode and smart font technologies 125 Javier Rodr´ıguez Laguna / H´ong-Z`ı: A Chinese METAFONT 129 Candy L. K. Yiu and Jim Binkley / Qin notation generator 135 Nandan Bagchee and Eitan M. Gurari / SwiExr: Spatial math exercises and worksheets, in Braille and print 142 Philip Taylor / Typesetting the Byzantine Cappelli 152 Hans Hagen / LuaTEX: Howling to the moon 158 Karel P´ıˇska / Converting METAFONT sources to outline fonts using METAPOST 165 S. K. Venkatesan / Moving from bytes to words to semantics 169 Abstracts (Beebe, Cho, H¨oppner, Hong, Rowley, Taylor) News 170 Calendar 174 TEX Collection 2005 ( TEX Live, proTEXt, MacTEX, CTAN) 175 EuroTEX 2006 announcement 176 TUG 2006 announcement TUG Business 172 TUG membership form 173 Institutional members Advertisements 173 TEX consulting and production services Index c3 Table of contents, ordered by difficulty TEX Users Group Board of Directors TUGboat (ISSN 0896-3207) is published by the Donald Knuth, Grand Wizard of TEX-arcana † ∗ TEX Users Group. Karl Berry, President Kaja Christiansen∗, Vice President Memberships and Subscriptions David Walden∗, Treasurer 2005 dues for individual members are as follows: Susan DeMeritt∗, Secretary Ordinary members: $75. Barbara Beeton Students/Seniors: $45. Lance Carnes The discounted rate of $45 is also available to Steve Grathwohl citizens of countries with modest economies, as Jim Hefferon detailed on our web site. -

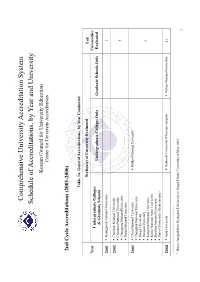

Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University

Comprehensive University Accreditation System Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University Korean Council for University Education Center for University Accreditation 2nd Cycle Accreditations (2001-2006) Table 1a: General Accreditations, by Year Conducted Section(s) of University Evaluated # of Year Universities Undergraduate Colleges Undergraduate Colleges Only Graduate Schools Only Evaluated & Graduate Schools 2001 Kyungpook National University 1 2002 Chonbuk National University Chonnam National University 4 Chungnam National University Pusan National University 2003 Cheju National University Mokpo National University Chungbuk National University Daegu University Daejeon University 9 Kangwon National University Korea National Sport University Sunchon National University Yonsei University (Seoul campus) 2004 Ajou University Dankook University (Cheonan campus) Mokpo National University 41 1 Name changed from Kyungsan University to Daegu Haany University in May 2003. 1 Andong National University Hanyang University (Ansan campus) Catholic University of Daegu Yonsei University (Wonju campus) Catholic University of Korea Changwon National University Chosun University Daegu Haany University1 Dankook University (Seoul campus) Dong-A University Dong-eui University Dongseo University Ewha Womans University Gyeongsang National University Hallym University Hanshin University Hansung University Hanyang University Hoseo University Inha University Inje University Jeonju University Konkuk University Korea -

South Korea 2018

Office of International Education Country Report South Korea Highlights UGA’s Department of Public Admin- istration has a dual M.P.A. degree with Seoul National University, where students earn degrees from both institutions by taking a year of courses at each. Public Administration also provides training to Korean public servants in the Min- istry of Personnel Management and sends UGA students to study civic government in Seoul each summer. South Korea is also a valuable partner for joint academic output with the main areas of co-publication including: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and Genetics and Heredity. South Korea sent the 3rd most international students to UGA in Fall 2016. January 2018 Active Partnerships Joint Publications UGA Students Abroad Rank Rank Rank 13 4 505 6 67 10 Visiting Scholars UGA Faculty Visits International Students Rank Rank 93 2 45 253 3 UGA Education Abroad in South Korea During the 2016-2017 academic year, 67 UGA students studied in South Korea, many of whom went on reciprocal student exchanges. Current study abroad programs in South Korea include: Program City/Destination Focus Korean Teaching Internship Nonsan Internship Seoul National University Seoul Dual Degree Dual MPA SPIA in Seoul Seoul Study Abroad Sogang University Seoul Exchange Yonsei University Seoul Exchange Yonsei University Interna- Fukuoka Summer School tional Summer School Academic Collaboration in Korea During 2007-2017, UGA faculty collaborated with colleagues in South Korea to joint- ly publish 505 scholarly articles. Top areas of cooperation during this period included: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and Genetics and Heredity. Top collaborating insti- tutions in South Korea during this period included Korea University and Seoul National University. -

College Codes (Outside the United States)

COLLEGE CODES (OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES) ACT CODE COLLEGE NAME COUNTRY 7143 ARGENTINA UNIV OF MANAGEMENT ARGENTINA 7139 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF ENTRE RIOS ARGENTINA 6694 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF TUCUMAN ARGENTINA 7205 TECHNICAL INST OF BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA 6673 UNIVERSIDAD DE BELGRANO ARGENTINA 6000 BALLARAT COLLEGE OF ADVANCED EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 7271 BOND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7122 CENTRAL QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7334 CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6610 CURTIN UNIVERSITY EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6600 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 7038 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6863 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7090 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6901 LA TROBE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6001 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6497 MELBOURNE COLLEGE OF ADV EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 6832 MONASH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7281 PERTH INST OF BUSINESS & TECH AUSTRALIA 6002 QUEENSLAND INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 6341 ROYAL MELBOURNE INST TECH EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6537 ROYAL MELBOURNE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 6671 SWINBURNE INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 7296 THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA 7317 UNIV OF MELBOURNE EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7287 UNIV OF NEW SO WALES EXCHG PROG AUSTRALIA 6737 UNIV OF QUEENSLAND EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 6756 UNIV OF SYDNEY EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7289 UNIV OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA EXCHG PRO AUSTRALIA 7332 UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE AUSTRALIA 7142 UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA AUSTRALIA 7027 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIA 7276 UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE AUSTRALIA 6331 UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND AUSTRALIA 7265 UNIVERSITY -

Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL Chapter Reports the Archive

Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL Chapter Reports The Archive Contents Chapter Reports 2004 – 2011 KOTESOL in Action, The English Connection (TEC) Chapter Reports 2011 – 2013 KOTESOL Chapter News, TEC News Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter Presidents 2004 Spring – 2005 November Maria Lisak 2005 November – 2006 March Scott Jackson 2006 March – 2008 March 15 Dr. Yeon-seong Park 2008 March 15 – 2009 November Adriane Moser Geronimo 2009 November – 2016 November Dr. David E. Shaffer 2016 November – 2017 November William Mulligan 2017 November – 2018 November Lindsay Herron 2018 November – Bryan Hale regions, and would then spread out to JEOLLA CHAPTER SEOUL CHAPTER those areas without a KOTESOL presence. At a later stage, we will cultivate speaking links with sister organizations and by Allison Bill by Tory Thorkelson governmental entities. To this end Dr. Robert Dickey has expressed interest in Perhaps the title for this section should As winter approaches, The Seoul chapter KTT giving presentations in the southern be Jeonbuk/Jeonnam Chapters (plural). By is gearing up for our regional conference part of the nation, possibly as early as the time you are reading this TEC, a in May, 2004. After a hiatus of 3 months January. Paul Mead has also expressed decision should have been made about for summer vacation, the YL SIG and the interest in doing this for the Pusan area, whether or not to split Jeolla Chapter into 11th KOTESOL International Conference, and Dr. Steve Garrigues will speak under two chapters: a Jeonju-Jeonbuk Chapter our monthly meetings resumed with a the KTT banner to a group in Taegu. So, in the north and a Gwangju-Jeonnam presentation on November 15th by our new we are off to a good start in 2004! Chapter in the south. -

Invertebrate Fauna of Korea

Invertebrate Fauna of Korea Volume 4, Number 3 Cnidaria: Hydrozoa Hydromedusae Flora and Fauna of Korea National Institute of Biological Resources Ministry of Environment National Institute of Biological Resources Ministry of Environment Russia CB Chungcheongbuk-do CN Chungcheongnam-do HB GB Gyeongsangbuk-do China GG Gyeonggi-do YG GN Gyeongsangnam-do GW Gangwon-do HB Hamgyeongbuk-do JG HN Hamgyeongnam-do HWB Hwanghaebuk-do HN HWN Hwanghaenam-do PB JB Jeollabuk-do JG Jagang-do JJ Jeju-do JN Jeollanam-do PN PB Pyeonganbuk-do PN Pyeongannam-do YG Yanggang-do HWB HWN GW East Sea GG GB (Ulleung-do) Yellow Sea CB CN GB JB GN JN JJ South Sea Invertebrate Fauna of Korea Volume 4, Number 3 Cnidaria: Hydrozoa Hydromedusae 2012 National Institute of Biological Resources Ministry of Environment Invertebrate Fauna of Korea Volume 4, Number 3 Cnidaria: Hydrozoa Hydromedusae Jung Hee Park The University of Suwon Copyright ⓒ 2012 by the National Institute of Biological Resources Published by the National Institute of Biological Resources Environmental Research Complex, Nanji-ro 42, Seo-gu Incheon, 404-708, Republic of Korea www.nibr.go.kr All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the National Institute of Biological Resources. ISBN : 9788994555836-96470 Government Publications Registration Number 11-1480592-000244-01 Printed by Junghaengsa, Inc. in Korea on acid-free paper Publisher : Yeonsoon Ahn Project Staff : Joo-Lae Cho, Ye Eun, Sang-Hoon Hahn Published on March 23, 2012 The Flora and Fauna of Korea logo was designed to represent six major target groups of the project including vertebrates, invertebrates, insects, algae, fungi, and bacteria. -

List AWS Educate Institutions

Educate Institution City Country 1337 KHOURIBGA Morocco 1daoyun 无锡 China 3aaa Apprenticeships Derby United Kingdom 3W Academy Paris France 42 São Paulo sao paulo Brazil 42 seoul seoul Korea, Republic of 42 Tokyo Minato-ku Tokyo Japan 42Quebec QUEBEC Canada A P Shah Institute of Technology Thane West India A. D. Patel Institute of Technology Ahmedabad India A.V.C. College of Engineering Mayiladuthurai India Aalim Muhammed Salegh College of Engineering Avadi-IAF India Aaniiih Nakoda College Harlem United States AARHUS TECH Aarhus N Denmark Aarhus University Aarhus Denmark Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology Kanchipuram(Dt) India Abb Industrigymansium Västerås Sweden Abertay University Dundee United Kingdom ABES Engineering College Ghaziabad India Abilene Christian University Abilene United States Research Pune Pune India Abo Akademi University Turku Finland Academia de Bellas Artes Semillas Ltda Bogota Colombia Academia Desafio Latam Santiago Chile Academia Sinica Taipei Taiwan Academie Informatique Quebec-Canada Lévis Canada Academy College Bloomington United States Academy for Career Exploration PROVIDENCE United States Academy for Urban Scholars Columbus United States ACAMICA Palermo Argentina Accademia di Belle Arti di Cuneo Cuneo Italy Achariya College of Engineering Technology Puducherry India Acharya Institute of Technology Bangalore India Acharya Narendra Dev College New Delhi India Achievement House Cyber Charter School Exton United States Acropolis Institute of Technology & Research, Indore Indore India ACT AMERICAN COLLEGE -

Female Korean Nursing Students' Views Toward Feminism

International Journal of General Medicine and Pharmacy (IJGMP) ISSN(P): 2319-3999; ISSN(E): 2319-4006 Vol. 8, Issue 5, Aug - Sep 2019; 1-10 © IASET FEMALE KOREAN NURSING STUDENTSVIEWS TOWARD FEMINISM Alaric Naudé Professor, Department of Nursing & English, Suwon Science College, University of Suwon, Hwaseong, Gyeonggi, South Korea ABSTRACT Korea is a strongly hierarchical Confucian society that within a social ideal focuses on “the greater good” rather than the individual. With the emphasis on saving face and maintaining stable social hierarchies, the study sought to understand female Korean nursing students’ perceptions of feminism. A total of 97 young women responded to the mixed- method study and the data showed that there were strongly mixed feelings toward feminism with even individuals who self- identified as being feminist critiquing the validity of “man-hating ideologies” common in modern feminism. Overall, opinion responses showed strong support for equality of the sexes but strong disapproval of “toxic femininity” which dominate 3rd and 4th Wave feminism. Understanding of nurses’ views toward feminism aids in discerning up-coming trends not only within society but also within the profession of nursing itself in Korea as well as other parts of East Asia KEYWORDS: Nursing, Feminism, Attitudes, Trends in Nursing, Misandry, Misogyny, Korean Studies Article History Received: 25 Apr 2019 | Revised: 17 Jul 2019 | Accepted: 22 Jul 2019 INTRODUCTION Korean society places great emphasis on the preservation of hierarchies and knowing ones -

Journal of the Ergonomics Society of Korea

eISSN : 2093-8462 / http://jesk.or.kr J Ergon Soc Korea JOURNAL OF THE ERGONOMICS SOCIETY OF KOREA Editor Dhong Ha Lee University of Suwon, [email protected] Editorial Board Woo Chang Cha Seung Kweon Hong Korea National Institute of Technology, [email protected] Korea National University of Transportation, [email protected] Dohyung Kee Byung Yong Jeong Keimyung University, [email protected] Hansung University, [email protected] Yong Gu Ji Kwang Tae Jung Yonsei University, [email protected] Korea University of Technology and Education, [email protected] Myung-Chul Jung Yong-Ku Kong Ajou University, [email protected] Sungkyunkwan University, [email protected] Kyung Tae Lee Young Hwan Pan Daebul University, [email protected] Kookmin University, [email protected] Hee Sok Park Peom Park Hongik University, [email protected] Ajou University, [email protected] Seung Bum Park Sungjoon Park Footwear Industrial Promotion Center, Korea, [email protected] Namseoul University, [email protected] Hoon Yong Yoon Myung Hwan Yun Donga University, [email protected] Seoul National University, [email protected] Manuscript Editor Sangwook Kim, [email protected] The Ergonomics Society of Korea (ESK) was founded in 1982 and is the largest nonprofit association for ergonomics professionals in Korea, with more than 2000 members. The purpose of the society is to contribute to development, distribution, and application of ergonomics technology for overall human and social well-being. The society focuses on the role of humans in a complex system, the design of process, procedures, software, products, equipment and facilities for human use, and the development of environments for comfort, safety and well-being. -

A U Tu M N 2 0 10 the ENGLISH CONNECTION

Volume 14, Issue 3 THE ENGLISH CONNECTION A Publication of Korea Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages Task-Based Language Teaching: Development of Academic Proficiency By Miyuki Nakatsugawa ask-based language teaching has continued to attract interest among second language acquisition (SLA) researchers and language Tteaching professionals. However, theoretically informed principles for developing and implementing a task-based syllabus have yet to be fully established. The Cognition Hypothesis (Robinson, 2005) claims that pedagogical tasks should be designed and sequenced in order of increased cognitive complexity in order to promote language development. This article will look at Robinson ss approach to task-based syllabus design as a What’s Inside? Continued on page 8. TeachingInvited Conceptions Speakers By PAC-KOTESOLDr. Thomas S.C. 2010 Farrell English-OnlyConference ClassroomsOverview ByJulien Dr. Sang McNulty Hwang Comparing EPIK and JET National Elections 2010 By Tory S. Thorkelson ThePre-Conference Big Problem of SmallInterview: Words By JulieDr. Alan Sivula Maley Reiter NationalNegotiating Conference Identity Program PresentationKueilan ChenSchedule Email us at [email protected] at us Email Autumn 2010 Autumn To promote scholarship, disseminate information, and facilitate cross-cultural understanding among persons concerned with the teaching and learning of English in Korea. www.kotesol.org The English Connection Autumn 2010 Volume 14, Issue 3 THE ENGLISH CONNECTION A Publication of Korea Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages Features Cover Feature: Task-Based Language Teaching -- Development of Academic Proficiency 1 By Miyuki Nakatsugawa Contents Featurette: Using Korean Culture 11 By Kyle Devlin Featured Focus: Enhancing Vocabulary Building 12 By Dr. Sang Hwang Columns President s Message:t Roll Up Your Sleeves u 5 By Robert Capriles From the Editor ss Desk: The Spirit of Professional Development 7 By Kara MacDonald Presidential Memoirs: KOTESOL 2008-09 -- Growing and Thriving 14 By Tory S. -

July 31(Sun) - August 6 (Sat), 2016 Daejeon Convention Center, Daejeon, Korea

1st Announcement July 31(Sun) - August 6 (Sat), 2016 Daejeon Convention Center, Daejeon, Korea Hope & Happiness: The role of home economics in the pursuit of hope & happiness for individuals and communities now and in the future Sponsored by DAEJEON METROPOLITAN CITY KOREA Invitation It gives me great pleasure to invite you to the 23rd IFHE World Congress 2016. Whether you are a passionate home economics professional or an interested allied professional, we invite you to participate in the global conversation that is IFHE World Congress. As indicated by our theme for 2016 - Hope and Happiness: The role of home economics in the pursuit of hope and happiness for individuals and communities now and in the future - we as home economists recognise that our profession is a key component of hope and happiness - critical for the wellbeing of individuals, families and communities. We also seek creative and innovative ways to communicate this message widely and effectively. As the only worldwide organisation concerned with home economics and consumer studies, it is imperative that IFHE seizes every opportunity to speak in full voice. World Congress gives us that opportunity. Since 1908, professionals, scholars and educators in home economics and allied fields have come together every four years to learn, share and inspire. Our consultative status with the United Nations and the Council of Europe gives us so much potential to extend congress outcomes and to see our resolutions put into action. We are pleased and excited to be staging IFHE World Congress in the Asian region for the first time since 2004. Daejeon, Korea, has built a reputation for the hosting of global conferences and is a hub for technology, education, research and development. -

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools KENYA 002859 Egerton

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools KENYA 002859 Egerton Univ 005018 Kenya Science Teachers Coll 000745 Kenyatta Univ Col 000743 Moi Univ 003189 Ngandu Girls' High School 000744 Royal Tech Col East Africa 046917 Strathmore College 000744 Univ Col Nairobi 000744 Univ Nairobi KOREA, DEMOCRATIC PPL'S REPUBLIC 001214 Kim Chaek Univ Tech 001213 Kim Il Sung Univ 001215 Pyongyang Univ Medicine KOREA, REPUBLIC OF 002120 Ajou Univ 002869 Anyang Univ 004303 Bae Myeong Hs 000366 Busan Na Univ. 002818 Busan Women'S University 002213 Catholic Medical Col 002952 Catholic University Of Korea 004062 Chang-An Junior College 002119 Cheju Na Univ 000367 Cho Sun Dae Hag Gyo 000367 Cho Sun Univ 000368 Chon Nam Dae Hag Gyo 046336 Chongju University 002186 Chongshin Col 000368 Chonnam Na Univ 000371 Choong Nam Na Univ 000371 Choonnam National University 046339 Chugye University for Arts 000369 Chung Ang Dae Hag Gyo 000369 Chung Ang Univ 000370 Chung Bug Dae Hag 000371 Chung Nam Dae Hag Gyo 000370 Chungbuk Na Univ 004696 Daewon Foreign Language Hs 004696 Daewon Girls' Sr Hs 004696 Daewon Jr Hs 004696 Daewon Sr Hs 000372 Dan Gug Dae Hag Gyo 000372 Dankook Univ 000373 Dong A Dae Hag Gyo 000373 Dong A Univ 000374 Dong Guk Dae Hag Gyo 002947 Dongdok Yoja Dae Hak 002947 Dongduck Women'S University 002947 Dongduk Women'S University International Schools 000374 Dongguk University 002245 Duksung Womens Col 000392 Ewha Womens Univ 000392 Ewha Womens University 002808 Gangnam Social Welfare College 000375 Go Lyeo Dae Hag Gyo 000377 Gyeong Sang Dae Hag Gyo 000377 Gyeong