The Fatal Splitting. Symbolizing Anxiety in Post-Soviet Russia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Template EUROVISION 2021

Write the names of the players in the boxes 1 to 4 (if there are more, print several times) - Cross out the countries that have not reached the final - Vote with values from 1 to 12, or any others that you agree - Make the sum of votes in the "TOTAL" column - The player who has given the highest score to the winning country will win, and in case of a tie, to the following - Check if summing your votes you’ve given the highest score to the winning country. GOOD LUCK! 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Anxhela Peristeri “Karma” Albania Montaigne “ Technicolour” Australia Vincent Bueno “Amen” Austria Efendi “Mata Hari” Azerbaijan Hooverphonic “ The Wrong Place” Belgium Victoria “Growing Up is Getting Old” Bulgaria Albina “Tick Tock” Croatia Elena Tsagkrinou “El diablo” Cyprus Benny Christo “ Omaga “ Czech Fyr & Flamme “Øve os på hinanden” Denmark Uku Suviste “The lucky one” Estonia Blind Channel “Dark Side” Finland Barbara Pravi “Voilà” France Tornike Kipiani “You” Georgia Jendrick “I Don’t Feel Hate” Germany Stefania “Last Dance” Greece Daði og Gagnamagnið “10 Years” Island Leslie Roy “ Maps ” Irland Eden Alene “Set Me Free” Israel 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Maneskin “Zitti e buoni” Italy Samantha Tina “The Moon Is Rising” Latvia The Roop “Discoteque” Lithuania Destiny “Je me casse” Malta Natalia Gordienko “ Sugar ” Moldova Vasil “Here I Stand” Macedonia Tix “Fallen Angel” Norwey RAFAL “The Ride” Poland The Black Mamba “Love is on my side” Portugal Roxen “ Amnesia “ Romania Manizha “Russian Woman” Russia Senhit “ Adrenalina “ San Marino Hurricane “LOCO LOCO” Serbia Ana Soklic “Amen” Slovenia Blas Cantó “Voy a quedarme” Spain Tusse “ Voices “ Sweden Gjon’s Tears “Tout L’Univers” Switzerland Jeangu Macrooy “ Birth of a new age” The Netherlands Go_A ‘Shum’ Ukraine James Newman “ Embers “ United Kingdom. -

Resilient Russian Women in the 1920S & 1930S

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 8-19-2015 Resilient Russian Women in the 1920s & 1930s Marcelline Hutton [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Modern Literature Commons, Russian Literature Commons, Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hutton, Marcelline, "Resilient Russian Women in the 1920s & 1930s" (2015). Zea E-Books. Book 31. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/31 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Marcelline Hutton Resilient Russian Women in the 1920s & 1930s The stories of Russian educated women, peasants, prisoners, workers, wives, and mothers of the 1920s and 1930s show how work, marriage, family, religion, and even patriotism helped sustain them during harsh times. The Russian Revolution launched an economic and social upheaval that released peasant women from the control of traditional extended fam- ilies. It promised urban women equality and created opportunities for employment and higher education. Yet, the revolution did little to elim- inate Russian patriarchal culture, which continued to undermine wom- en’s social, sexual, economic, and political conditions. Divorce and abor- tion became more widespread, but birth control remained limited, and sexual liberation meant greater freedom for men than for women. The transformations that women needed to gain true equality were post- poned by the pov erty of the new state and the political agendas of lead- ers like Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin. -

Boulder International Film Festival

FilmBoulder Festival International movesi celebrating the bold spirit >> welcome Welcome to the 7th Annual Boulder International Film Festival, a non-profit community festival staffed almost entirely by energized volunteers and voted “one of the coolest film festivals in the world” byMovieMaker magazine. That’s because of you, the huge, film-hip, Boulder audiences who show up by the thousands to be a part of the big world of ideas and passions that are light- years beyond the normal muck of American mass corporate media. This year’s BIFF will honor one of the greatest, most thought-provoking film directors of our time—three-time Oscar winner Oliver Stone (Midnight Express, Platoon, Born on the Fourth of July). Mr. Stone will receive BIFF’s Master of Cinema Award and sit down for an in-depth interview and retrospective of his films at the Closing Night ceremonies on Sunday night. Last year, BIFF welcomed Alec Baldwin just weeks before he co-hosted the 2010 Academy Awards. Continuing that tradition, we are excited to present voteWHAT ROCKS YOU AT BIFF? 2011’s Oscar co-host, movie mega-star James Franco (the Spider-Man trilogy, Get a ballot on your way in to Milk, Howl, 127 Hours) for an evening retrospective of his films. - each program. Take 10 sec BIFF is happy to welcome back Oscar-nominated producer Don Hahn (Beauty onds to vote. Hand it back on and the Beast, The Lion King) who will present his touching new film,Hand your way out. Easy! Bribes not Held. Mr. Hahn will also be a moderator of honor for a reprise of one of the accepted. -

There's a Common Misconception About Eurovision Songs

First Half Second Half The Stats The Rest Hello, Rotterdam! After a year in storage, it’s time to dust off Europe’s most peculiar pop tradition and watch as singers from every corner of the continent come to do battle. As ever, we’ve compiled a full guide to the most bizarre, brilliant and boring things the contest has to offer... ////////////////////////////////// The First Half...............3-17 Cypriot Satan worshipping! Homemade Icelandic indie-disco! 80s movie montages and gigantic Russian dolls! Unusually for Eurovision, the first half features some of this year’s hot favourites, so you’ll want to be tuned in from the start. The Second Half.............19-33 Finnish nu-metal! Angels with Tourette’s! A Ukrainian folk- rave that sounds like Enya double-dropping and Flo Fucking Rida! Things start getting a little bit weirder here, especially if you’re a few drinks in, but we’re here to hold your hand. The Stats...................34-42 Diagrams, facts, information, theory. You want to impress your mates with absolutely useless knowledge about which sorts of things win? We’ve got everything you need... The Ones We Left Behind.....43-56 If you didn’t catch the semis, you’ll have missed some mad stuff fall by the wayside. To honour those who tripped at the first hurdle, we’ve kept their profiles here for posterity – so you’ll never need ask “Who was the Polish Bradley Walsh?” First Half Second Half The Stats The Rest Pt.1: At A Glance The Grand Final’s first half is filled with all your classic Saturday night Europop staples. -

Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 11-2013 Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry Marcelline Hutton [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Slavic Languages and Societies Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hutton, Marcelline, "Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry" (2013). Zea E-Books. 21. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/21 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry N Marcelline Hutton Many Russian women of the late 19th and early 20th centuries tried to find happy marriages, authentic religious life, liberal education, and ful- filling work as artists, doctors, teachers, and political activists. Some very remarkable ones found these things in varying degrees, while oth- ers sought unsuccessfully but no less desperately to transcend the genera- tions-old restrictions imposed by church, state, village, class, and gender. Like a Slavic “Downton Abbey,” this book tells the stories, not just of their outward lives, but of their hearts and minds, their voices and dreams, their amazing accomplishments against overwhelming odds, and their roles as feminists and avant-gardists in shaping modern Russia and, in- deed, the twentieth century in the West. -

The Russian Woman As Sexual Subject

THE RUSSIAN WOMAN AS SEXUAL SUBJECT: EVOLVING IMAGES IN U.S. TELEVISION AND FILM, 2012-2016 by AUDREY JANE BLACK A THESIS Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2016 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Audrey Jane Black Title: The Russian Woman as Sexual Subject: Evolving Images in U.S. Television and Film, 2012-2016 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Journalism and Communication by: Gretchen Soderlund Chairperson Chris Chávez Member Katya Hokanson Member and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2016 ii © 2016 Audrey Jane Black iii THESIS ABSTRACT Audrey Jane Black Master of Arts School of Journalism and Communication June 2016 Title: The Russian Woman as Sexual Subject: Evolving Images in U.S. Television and Film, 2012-2016 In American entertainment media Russian women overwhelmingly appear in sexualized contexts. For the past 25 years, since the Soviet Union was dissolved, there has been a consistent drive to represent on only a handful of narrative categories. These can be reduced essentially to sex trafficking, mail-order brides, and sexual espionage. Despite this limited repertoire, over the past five years there has been significant variation in approaches taken to those categories. This study offers a surveyed textual analysis of how the construction of the Russian woman as sexual subject has evolved to meet new understandings and imperatives. -

Reflections of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin, 1833-2014

Constructing the Russian Moral Project through the Classics: Reflections of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, 1833-2014 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Emily Alane Erken Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Danielle Fosler-Lussier, Advisor Alexander Burry Ryan Thomas Skinner Copyright by Emily Alane Erken 2015 Abstract Since the nineteenth century, the Russian intelligentsia has fostered a conversation that blurs the boundaries of literature, the arts, and life. Bypassing more direct modes of political discourse blocked by Imperial and then Soviet censorship, arts reception in Russia has provided educated Russians with an alternative sphere for the negotiation of social, moral, and national identities. This discursive practice has endured through the turbulent political changes of the Russian revolution, Soviet repression, and the economic anxiety of contemporary Russia. Members of the intelligentsia who believe that individuals can and should work for the moral progress of the Russian people by participating in this conversation are constructing the Russian moral project. Near the end of the nineteenth century, members of the intelligentsia unofficially established a core set of texts and music—Russian klassika—that seemed to represent the best of Russian creative output. Although the canon seems permanent, educated Russians continue to argue about which texts are important and what they mean. Even Aleksandr Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin (1825-1833), a novel-in-verse that functions as the cornerstone of this canon, remains at the center of debate in a conversation about literature that is simultaneously a conversation about Russian life. -

Friday 23 Lifestyle | Features Friday, May 21, 2021

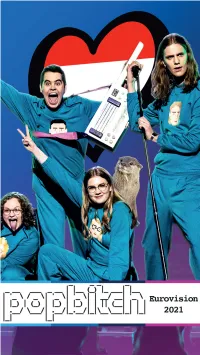

Friday 23 Lifestyle | Features Friday, May 21, 2021 utch 2019 Eurovision Song Contest different form”, the organizers said. “Duncan competition in the Dutch port city, which was winner Duncan Laurence has tested is very disappointed, he has been looking cancelled last year due to COVID-19 and is Dpositive for coronavirus and will be forward to this for two years. We are very going ahead this year with strict health unable to perform live at tomorrow’s grand happy that he will still be seen in the final,” measures. final in Rotterdam, the organizers said. The his management said in a statement. The “We have all been extremely careful the fresh blow for the contest-which was can- Dutch singer is the latest in a series of peo- whole trip so this comes as a huge sur- celled last year because of the pandemic ple to test positive at what is meant to be a prise,” tweeted singer Dadi, who like the rest and is going ahead under strict conditions- strictly COVID-controlled environment at of the band performs in a green tracksuit comes after members of the Iceland and Eurovision. with an emoji of his face on the front. “We Poland delegations also tested positive. are very happy with the performance and Laurence, who won with the power ballad Iceland Eurovision winner super excited for you all to see it! Thank you “Arcade” in Tel Aviv two years ago, devel- tested positive for all the love.” The European Broadcasting oped “mild symptoms” of COVID-19 on Iceland’s Eurovision Song Contest con- Union said in a statement that a member of Wednesday after taking part in a dress tender, one of this year’s favorites to win, the Icelandic group tested positive on rehearsal at the Ahoy Arena the previous will also miss the live shows in Rotterdam Wednesday as did a member of the day, Eurovision said. -

Europack Full 2021.Pdf

WELCOME Bienvenidos/as Eurovision-Spain tiene mucho que celebrar este 2021, nuestro recién cumplido 20º aniversario, el nuevo diseño de la web y APP, la celebración de la quinta PrePartyES y, especialmente, y el regreso de Eurovisión a nuestras vidas. Para que puedas disfrutarlo como merece la ocasión, he aquí nuestro tradicional Europack, con toda la información del festival de Róterdam que culminará el próximo sábado 22 de mayo y disfrutaremos juntos desde la primera jornada de ensayos del día 8. A ti, querido lector, gracias por seguir ahí un año más, una edición más. LITUANIA 01 LITHUANIA SF 1 DISCOTEQUE THE ROOP LETRA | LYRIC Okay, I feel the rhythm My body’s shaking, heart is Something’s going on here breaking The music flows through my veins Have to let it go It’s taking over me, it’s slowly I need to get up and put my kicking in hands up My eyes are blinking and I don’t There’s no one here and I don’t know what is happening care I can’t control it, don’t wanna end it I feel it’s safe to dance alone There’s no one here and I don’t care Let’s discoteque right at my I feel it’s safe to dance alone (dance home alone) It is okay to dance alone Dance alone (dance alone), dance Dance alone, dance alone (alone) alone (dance alone) Dance alone (alone), dance alone Dance alone (dance alone), dance (alone) alone (dance alone) I got the moves, it’s gonna blow Dance alone (dance alone), dance Dance alone, dance alone alone Dance alone, dance alone Let’s discoteque right at my home Let’s discoteque right at my It is okay to dance alone home -

Semi Final 1 Semi Final 2 the Big Six the Stats

Semi Final 1 Semi Final 2 The Big Six The Stats Hello, Rotterdam! After a year in storage, it’s time to dust off Europe’s most peculiar pop tradition and watch as singers from every corner of the continent come to do battle. As ever, we’ve compiled a full guide to the most bizarre, brilliant and boring things the contest has to offer... ////////////////////////////////// Semi Final 1.................3-21 Tuesday’s semi is the stronger of the two, with Cypriot- censured Satanism, bloopy Lithuanian club-pop and a wailing Ukrainian rave that will leave your head spinning. Expect upsets galore as the favourites all fight for a place. Semi Final 2................22-34 A slightly more standard affair, there’s less of the outright bonkers stuff on Thursday – but there’s still a couple of acts that you won’t want to miss, including Polish TV hosts, Danish 80s throwbacks and a possible cameo from Flo Rida. The Big Six.................41-47 When acts have a guaranteed place in the final, that’s usually an excuse to phone stuff in – but France and Italy are hot favourites this year (and Germany is a hot mess) so the Big Six are well worth a preview. The Stats...................48-56 Diagrams, facts, information, theory. You want to impress your mates with absolutely useless knowledge about which sorts of things win? We’ve got everything you need... Semi Final 1 Semi Final 2 The Big Six The Stats SF 1: At A Glance Of the two semi-finals, this is the one that has the potential to cause the greatest upset. -

96 Sport Life Билтенбр. 37 14.5.2021

Eurovision Song Contest - To Win Outright Eurovision Song Contest - 1st Semi-Final Winner Eurovision Song Contest - 1st Semi-Final To Qualify победник победник победник време време време шифра квота шифра квота шифра квота Саб 21:00 Malta 9000 4.00 Вто 21:00 Malta 9131 1.50 Вто 21:00 Australia 9085 2.60 Саб 21:00 France 9001 5.00 Вто 21:00 Cyprus 9132 5.00 Вто 21:00 Azerbaijan 9086 1.50 Саб 21:00 Switzerland 9002 7.00 Вто 21:00 Ukraine 9133 8.00 Вто 21:00 Belgium 9087 2.00 Саб 21:00 Iceland 9003 8.00 Вто 21:00 Lithuania 9134 11.0 Вто 21:00 Croatia 9088 1.40 Саб 21:00 Italy 9004 8.00 Вто 21:00 Sweden 9135 11.0 Вто 21:00 Cyprus 9089 1.02 Саб 21:00 Bulgaria 9005 10.0 Вто 21:00 Russia 9136 20.0 Вто 21:00 Israel 9090 1.55 Саб 21:00 Cyprus 9006 15.0 Вто 21:00 Romania 9137 23.0 Вто 21:00 Ireland 9091 3.25 Саб 21:00 Lithuania 9007 30.0 Вто 21:00 Norway 9138 23.0 Вто 21:00 Lithuania 9092 1.07 Саб 21:00 Ukraine 9008 30.0 Вто 21:00 Israel 9139 35.0 Вто 21:00 Malta 9093 1.01 Саб 21:00 Greece 9010 40.0 Вто 21:00 Croatia 9140 35.0 Вто 21:00 Macedonia 9094 5.50 Саб 21:00 Finland 9011 40.0 Вто 21:00 Belgium 9141 35.0 Вто 21:00 Norway 9095 1.40 Саб 21:00 Sweden 9012 40.0 Вто 21:00 Azerbaijan 9142 40.0 Вто 21:00 Romania 9099 1.45 Саб 21:00 San Marino 9013 55.0 Вто 21:00 Ireland 9143 125 Вто 21:00 Russia 9100 1.15 Саб 21:00 Russia 9014 60.0 Вто 21:00 Australia 9144 150 Вто 21:00 Slovenia 9101 4.00 Саб 21:00 Norway 9015 70.0 Вто 21:00 Macedonia 9145 200 Вто 21:00 Sweden 9103 1.15 Саб 21:00 Croatia 9021 125 Вто 21:00 Slovenia 9711 200 Вто 21:00 Ukraine 9104 -

Teaching the Narod to Listen: Nadezhda Briusova and Mass Music Education in Revolutionary Russia

Teaching the Narod to Listen: Nadezhda Briusova and Mass Music Education in Revolutionary Russia By Annika Krafcik Candidate for Senior Honors Oberlin College History Department Advisors: Annemarie Sammartino, Leonard Smith Submitted: April 2020 Krafcik, 2 Table of Contents: Preface and Acknowledgements......................................................................................................3 Introduction......................................................................................................................................7 Chapter 1: "Nadezhda Briusova: The Matroyshka of Mass Music Education".............................20 Chapter 2: "Who is the narod?: Pedagogy and Politics in Briusova's Mass Music Education Program..........................................................................................................................................43 Chapter 3: Folk Song and Russian Classics: Cultural Nationalism in Briusova's Pedagogy........61 Conclusion.....................................................................................................................................77 Glossary of Terms..........................................................................................................................81 Photo Gallery.................................................................................................................................83 Bibliography..................................................................................................................................86