American Indian Identities: Issues of Individual Choices and Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Indian Revolutionaries. the American Indian Movement in the 1960S and 1970S

5 7 Radosław Misiarz DOI: 10 .15290/bth .2017 .15 .11 Northeastern Illinois University The Indian Revolutionaries. The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s The Red Power movement1 that arose in the 1960s and continued to the late 1970s may be perceived as the second wave of modern pan-Indianism 2. It differed in character from the previous phase of the modern pan-Indian crusade3 in terms of massive support, since the movement, in addition to mobilizing numerous groups of urban Native Americans hailing from different tribal backgrounds, brought about the resurgence of Indian ethnic identity and Indian cultural renewal as well .4 Under its umbrella, there emerged many native organizations devoted to address- ing the still unsolved “Indian question ”. The most important among them were the 1 The Red Power movement was part of a broader struggle against racial discrimination, the so- called Civil Rights Movement that began to crystalize in the early 1950s . Although mostly linked to the African-American fight for civil liberties, the Civil Rights Movement also encompassed other racial and ethnic minorities including Native Americans . See F . E . Hoxie, This Indian Country: American Indian Activists and the Place They Made, New York 2012, pp . 363–380 . 2 It should be noted that there is no precise definition of pan-Indianism among scholars . Stephen Cornell, for instance, defines pan-Indianism in terms of cultural awakening, as some kind of new Indian consciousness manifested itself in “a set of symbols and activities, often derived from plains cultures ”. S . Cornell, The Return of the Native: American Indian Political Resurgence, New York 1988, p . -

Emerging Paradigms in Critical Mixed Race Studies G

Emerging Paradigms in Critical Mixed Race Studies G. Reginald Daniel, Laura Kina, Wei Ming Dariotis, and Camilla Fojas Mixed Race Studies1 In the early 1980s, several important unpublished doctoral dissertations were written on the topic of multiraciality and mixed-race experiences in the United States. Numerous scholarly works were published in the late 1980s and early 1990s. By 2004, master’s theses, doctoral dissertations, books, book chapters, and journal articles on the subject reached a critical mass. They composed part of the emerging field of mixed race studies although that scholarship did not yet encompass a formally defined area of inquiry. What has changed is that there is now recognition of an entire field devoted to the study of multiracial identities and mixed-race experiences. Rather than indicating an abrupt shift or change in the study of these topics, mixed race studies is now being formally defined at a time that beckons scholars to be more critical. That is, the current moment calls upon scholars to assess the merit of arguments made over the last twenty years and their relevance for future research. This essay seeks to map out the critical turn in mixed race studies. It discusses whether and to what extent the field that is now being called critical mixed race studies (CMRS) diverges from previous explorations of the topic, thereby leading to formations of new intellectual terrain. In the United States, the public interest in the topic of mixed race intensified during the 2008 presidential campaign of Barack Obama, an African American whose biracial background and global experience figured prominently in his campaign for and election to the nation’s highest office. -

Am I Enough? a Multi-Race Teacher’S Experience In-Between Contested Race, Gender, Class, and Power

FEATURE ARTICLE Am I Enough? A Multi-Race Teacher’s Experience In-Between Contested Race, Gender, Class, and Power SONIA JANIS University of Georgia AM NOT WHITE. I am not Black. I am mixed. I am one half Polish, one quarter Russian, and one-quarter Japanese. I was born, raised, and educated in public schools in the suburbs of Chicago, and then abruptly transitioned to public schools located in north Alabama when I was an adolescent. My inquiry explores my mixed race experience of childhood, adolescence, college years, teaching and administration positions, pursuing curriculum studies, and working as a pre-service teacher educator in a predominantly White institution. My inquiry explores the spaces in-between race and place from my perspective as an educator who is multiracial and/or hapa according to the latest race-based verbiage. I search for language to portray the experience of people of mixed race such as myself and come across a long list of such words as: Afroasian, Ainoko, Ameriasian, biracial, Eurasian, Haafu, half-breed, hapa haole or hapa, griffe, melange, mestizo(a), miscegenation, mixie, mono-racial, mulatto(a), multiracial, octoroon, quadroon, spurious issue, trans-racial, and zebra (Broyard, 2007; Murphy-Shigematsu, 2001; Root, 1996a; Spencer, 1999). I find that most of these words, whether they are verbs, nouns, or adjectives, have negative connotations. I use “multiracial,” “biracial,” and “mixed race” interchangeably throughout my writing. As I reflect on my experience as a seventh grade student, a public school administrator, and now as a pre-service teacher educator in a predominantly White institution, I explore my rememory (Morrison, 1990) of lives in two distinct regions of the United States: the Midwest and the South. -

NAS 204 the Native American Experience

NAS 204 The Native American Experience Winter 20 Tuesday 6-9:20 pm JXJ 1311 Instructor Shirley Brozzo [email protected] Office: 3001 Hedgcock Cell 906-360-5406 NO calls after 10 pm Multicultural Ed & Res. Center Pronouns: she/her/hers Office phone: 906-227-1554 3 required texts Benton Banai, Eddie The Mishomis Book Child, Brenda editor Boarding School Seasons Lobo, Talbot, Morris Native American Voices, 3rd Edition Weekly Assignments: Have these pages read when you come to class each week Jan 14 Introduction, initial drawings, tribal listings, description of presentations Video: More Than Bows and Arrows 21 CULTURE AND CUSTOMS: Read the Mishomis Book 28 IDENTITY AND ORAL TRADITIONS: Read Native American Voices Part I: Introduction pages 2-9 Part I Ch 3: Indigenous Identity: What Is It, and Who Really Has It pgs 28-35 Part 1 short section: Native American Demographics pgs 45-47 Part 1 short section: The US Census pg 48 Part III: Introduction pgs 95-100 Part III Ch 1: 500 Years of Injustice… pgs 101-104 Part V Ch 3 But is It American Indian Art? Pgs 214-221 ECOLOGY AND LAND TRADITIONS Part III Ch 3: The Black Hills: Sacred Land of the Lakota... pgs 113-119 Part VII: Introduction pgs 308-309 Feb 4 Test # 1 100 points Video: American Outrage 11 BOARDING SCHOOLS: Read Boarding School Seasons Video: In the Whiteman's Image 18 MORE SCHOOLING: Read Native American Voices Part II Ch 5: Just Speak Your Language… pgs 90-92 Part VI Introduction, pgs 238-245 Part VI Ch 6: If We Get the Girls… pgs 284-291 Part VI Ch 7: Protagonism Emergent… pgs 292-300 -

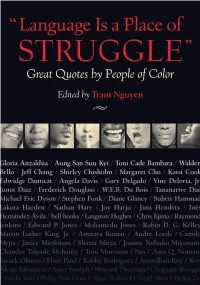

"Language Is a Place of Struggle" : Great Quotes by People of Color

“Language Is a Place of STRUGGLE” “Language Is a Place of STRUGGLE” Great Quotes by People of Color Edited by Tram Nguyen Beacon Press, Boston A complete list of quote sources for “Language Is a Place of Struggle” can be located at www.beacon.org/nguyen Beacon Press 25 Beacon Street Boston, Massachusetts 02108-2892 www.beacon.org Beacon Press books are published under the auspices of the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations. © 2009 by Tram Nguyen All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 12 11 10 09 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper that meets the uncoated paper ANSI/NISO specifications for permanence as revised in 1992. Text design by Susan E. Kelly at Wilsted & Taylor Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Language is a place of struggle : great quotes by people of color / edited by Tram Nguyen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8070-4800-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Minorities—United States—Quotations. 2. Immigrants—United States—Quotations. 3. United States—Race relations—Quotations, maxims, etc. 4. United States—Ethnic relations—Quotations, maxims, etc. 5. United States—Social conditions—Quotations, maxims, etc. 6. Social change—United States—Quotations, maxims, etc. 7. Community life—United States—Quotations, maxims, etc. 8. Social justice—United States— Quotations, maxims, etc. 9. Spirituality—Quotations, maxims, etc. I. Nguyen, Tram. E184.A1L259 2008 305.8—dc22 2008015487 Contents Foreword vii Chapter 1 Roots -

Reconsidering the Relationship Between New Mestizaje and New Multiraciality As Mixed-Race Identity Models1

Reconsidering the Relationship Between New Mestizaje and New Multiraciality as Mixed-Race Identity Models1 Jessie D. Turner Introduction Approximately one quarter of Mexican Americans marry someone of a different race or ethnicity— which was true even in 1963 in Los Angeles County—with one study finding that 38 percent of fourth- generation and higher respondents were intermarried.1 It becomes crucial, therefore, to consider where the children of these unions, a significant portion of the United States Mexican-descent population,2 fit within current ethnoracial paradigms. As such, both Chicana/o studies and multiracial studies theorize mixed identities, yet the literatures as a whole remain, for the most part, non-conversant with each other. Chicana/o studies addresses racial and cultural mixture through discourses of (new) mestizaje, while multiracial studies employs the language of (new) multiraciality.3 Research on the multiracially identified population focuses primarily on people of African American and Asian American, rather than Mexican American, backgrounds, whereas theories of mestizaje do not specifically address (first- and second- generation) multiracial experiences. In fact, when I discuss having parents and grandparents of different races, I am often asked by Chicana/o studies scholars, “Why are you talking about being multiracial as if it were different from being mestiza/o? Both are mixed-race experiences.” With the limitations of both fields in mind, I argue that entering these new mixed-identity discourses into conversation through an examination of both their significant parallels and divergences accomplishes two goals. First, it allows for a more complete acknowledgement and understanding of the unique nature of multiracial Mexican-descent experiences. -

Popular Culture Imaginings of the Mulatta: Constructing Race, Gender

Popular Culture Imaginings of the Mulatta: Constructing Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Nation in the United States and Brazil A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Jasmine Mitchell IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Bianet Castellanos, Co-adviser Erika Lee, Co-adviser AUGUST 2013 © Jasmine Mitchell 2013 Acknowledgements This dissertation would have been impossible without a community of support. There are many numerous colleagues, family, friends, and mentors that have guided ths intellectual and personal process. I would first like to acknowledge my dissertation committee for their patience, enthusiasm, and encouragement while I was in Minneapolis, New York, São Paulo, and everywhere in between. I am thankful for the research and methodological expertise they contributed as I wrote on race, gender, sexuality, and popular culture through an interdisciplinary and hemispheric approach. Special gratitude is owed to my co-advisors, Dr. Bianet Castellanos and Dr. Erika Lee for their guidance, commitment, and willingness to read and provide feedback on multiple drafts of dissertation chapters and applications for various grants and fellowships to support this research. Their wisdom, encouragement, and advice for not only this dissertation, but also publications, job searches, and personal affairs were essential to my success. Bianet and Erika pushed me to rethink the concepts used within the dissertation, and make more persuasive and clearer arguments. I am also grateful to my other committee members, Dr. Fernando Arenas, Dr. Jigna Desai, and Dr. Roderick Ferguson, whose advice and intellectual challenges have been invaluable to me. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: SLAVE SHIPS, SHAMROCKS, AND SHACKLES: TRANSATLANTIC CONNECTIONS IN BLACK AMERICAN AND NORTHERN IRISH WOMEN’S REVOLUTIONARY AUTO/BIOGRAPHICAL WRITING, 1960S-1990S Amy L. Washburn, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Professor Deborah S. Rosenfelt Department of Women’s Studies This dissertation explores revolutionary women’s contributions to the anti-colonial civil rights movements of the United States and Northern Ireland from the late 1960s to the late 1990s. I connect the work of Black American and Northern Irish revolutionary women leaders/writers involved in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Black Panther Party (BPP), Black Liberation Army (BLA), the Republic for New Afrika (RNA), the Soledad Brothers’ Defense Committee, the Communist Party- USA (Che Lumumba Club), the Jericho Movement, People’s Democracy (PD), the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP), the National H-Block/ Armagh Committee, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), Women Against Imperialism (WAI), and/or Sinn Féin (SF), among others by examining their leadership roles, individual voices, and cultural productions. This project analyses political communiqués/ petitions, news coverage, prison files, personal letters, poetry and short prose, and memoirs of revolutionary Black American and Northern Irish women, all of whom were targeted, arrested, and imprisoned for their political activities. I highlight the personal correspondence, auto/biographical narratives, and poetry of the following key leaders/writers: Angela Y. Davis and Bernadette Devlin McAliskey; Assata Shakur and Margaretta D’Arcy; Ericka Huggins and Roseleen Walsh; Afeni Shakur-Davis, Joan Bird, Safiya Bukhari, and Martina Anderson, Ella O’Dwyer, and Mairéad Farrell. -

Comparative Cultures Lakota Woman

COMPARATIVE CULTURES LAKOTA WOMAN I have prepared some questions for you to answer as while reading Mary Brave Bird Crow Dog’s autobiography. This book is a personal account of the American Indian Movement from the point of view of those involved. *** At the end of each chapter, after answering my question in one paragraph, write another paragraph about what struck you most about the chapter. Give me your reaction and thoughts about what Mary has said. *** (So, I’m expecting two paragraphs for each chapter, about five to six pages total.) Chapter 1: What Indian nation does Mary belong to? Where is she from? Why is Mary prouder of her husband’s family than she is of her own? Chapter 2: What was one incident of racism Mary encountered growing up? Chapter 3: What does Mary say are the differences between traditional Lakota child-rearing and Indian schools? Why did Mary leave school? Chapter 4: Why did Mary begin drinking? What does she think causes the “Indian drinking problem?” Chapter 5: What was Mary’s life like as a teenager? How do you think you would have reacted under similar conditions? Chapter 6: Describe the Trail of Broken Treaties and the takeover of the BIA. Chapter 7: What is the significance of peyote in Indian religion? What does Mary think about non-Indian use of peyote? Chapter 8: Why did the Indians pick Wounded Knee to make a stand? How did Mary end up there? Chapter 9: What were conditions like during the siege at Wounded Knee? What was the government’s reaction to the occupation? Do you think the government overreacted? What could have the government done instead? Chapter 10: Why did Crow Dog revive the Ghost Dance? Describe the original Ghost Dance. -

He Uses of Humor in Native American and Chicano/A Cultures: an Alternative Study Of

The Uses of Humor in Native American and Chicano/a Cultures: An Alternative Study of Their Literature, Cinema, and Video Games Autora: Tamara Barreiro Neira Tese de doutoramento/ Tesis doctoral/ Doctoral Thesis UDC 2018 Directora e titora: Carolina Núñez Puente Programa de doutoramento en Estudos Ingleses Avanzados: Lingüística, Literatura e Cultura Table of contents Resumo .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Resumen ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Sinopsis ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 21 1. Humor and ethnic groups: nonviolent resistance ................................................................ 29 1.1. Exiles in their own land: Chicanos/as and Native Americans ..................................... 29 1.2. Humor: a weapon of mass creation ............................................................................. 37 1.3. Inter-Ethnic Studies: combining forces ...................................................................... -

Narratives of Ethnic and Racial Identity Experiences of Asian

Locating Identity: Narratives of Ethnic and Racial Identity Experiences of Asian American Student Leaders of Ethnic Student Organizations Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Annabelle Lina Estera Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2013 Thesis Committee: Dr. Susan Robb Jones, Advisor Dr. Tatiana Suspitsyna Copyright by Annabelle Lina Estera 2013 Abstract The purpose of this constructivist narrative study was to explore how Asian American student leaders of ethnic student organizations (ESOs) experience their ethnic and racial identities in the context of their ESO and the classroom. The primary research questions guiding this study were: (a) How do Asian American student leaders of ESOs experience and make sense of their ethnic and racial identities within the context of their involvement with their ESO; (b) How do Asian American student leaders of ESOs experience and make sense of their ethnic and racial identities within the classroom? Data collection included semi-structured interviews with six participants. Data was analyzed through Clandinin and Connelly’s “three dimensional narrative inquiry space” (2000, p. 49) for elements of interaction, continuity, and situation. Restories of each participants’ narrative were presented. Findings from this study include: (1) Complex and varied understandings and negotiations of ethnic and racial identities within the ESO context; and (2) Salience of ethnic and racial identity in the classroom associated with negative, challenging, and positive experiences. ii Acknowledgments I offer my deepest gratitude to Dr. Susan R. Jones for her guidance throughout this process. -

Multiracial Identity in Visual Culture

[mix]understandings multiracial identity in visual culture MELANIE FEASTER In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Exhibition Design Corcoran College of Art + Design Washington DC PRO-THESIS/EX7900/STUDIO A PHILIP BRADY SPRING 2012/ SP01 MAY 2013 [MIX]UNDERSTANDINGS: MULTIRACIAL IDENTITY IN VISUAL CULTURE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Exhibition Design at Corcoran College of Art and Design By Melanie Feaster Bachelor of Arts University of Maryland, Baltimore County, 2010 Advisor: Philip Brady Exhibition Design Spring Semester 2013 Corcoran College of Art + Design Washington, D.C. Copyright: 2013 Melanie Feaster All Rights Reserved MELANIE FEASTER CCA+D MASTER OF ARTS IN EXHIBITION DESIGN THESIS/EX7900/STUDIO A SPRING 2013/ SP01 May 14, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures………………………………………………………………………..ii Abstract………………………………………………………………………………iii Mission Statement……………………………………………………………………1 Exhibition Branding………………………………………………………………….2 Teaching Points and Take-Away…………………………………………………….4 Target Audience……………………………………………………………………...5 Venue………………………………………………………………………………...6 Exhibit Content Outline……………………………………………………………...14 Resources…………………………………………………………………………….54 Resource Organization Diagram……………………………………………………..55 Visitor Experience Narrative…………………………………………………………56 List of Illustration References………………………………………………………..64 List of References…………………………………………………………………….65 i MELANIE FEASTER CCA+D MASTER OF ARTS IN EXHIBITION DESIGN THESIS/EX7900/STUDIO A SPRING 2013/ SP01 May 14, 2013 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page Fig. 1 Geffen Contemporary location in Los Angeles, CA…………………………...7 Fig. 2 Geffen Contemporary in relation to Japanese American National Museum…..7 Fig. 3 Satellite View of Geffen Contemporary……………………………………….7 Fig. 4 Entrance to the Geffen Contemporary………………………………………...10 Fig. 5 Geffen Contemporary Annex…………………………………………………10 Fig. 6 Sample Elevations of the Geffen Contemporary……………………………...11 Fig.