Dissertation Zur Erlangung Des Doktorgrades Der Philosophie an Der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Indian Revolutionaries. the American Indian Movement in the 1960S and 1970S

5 7 Radosław Misiarz DOI: 10 .15290/bth .2017 .15 .11 Northeastern Illinois University The Indian Revolutionaries. The American Indian Movement in the 1960s and 1970s The Red Power movement1 that arose in the 1960s and continued to the late 1970s may be perceived as the second wave of modern pan-Indianism 2. It differed in character from the previous phase of the modern pan-Indian crusade3 in terms of massive support, since the movement, in addition to mobilizing numerous groups of urban Native Americans hailing from different tribal backgrounds, brought about the resurgence of Indian ethnic identity and Indian cultural renewal as well .4 Under its umbrella, there emerged many native organizations devoted to address- ing the still unsolved “Indian question ”. The most important among them were the 1 The Red Power movement was part of a broader struggle against racial discrimination, the so- called Civil Rights Movement that began to crystalize in the early 1950s . Although mostly linked to the African-American fight for civil liberties, the Civil Rights Movement also encompassed other racial and ethnic minorities including Native Americans . See F . E . Hoxie, This Indian Country: American Indian Activists and the Place They Made, New York 2012, pp . 363–380 . 2 It should be noted that there is no precise definition of pan-Indianism among scholars . Stephen Cornell, for instance, defines pan-Indianism in terms of cultural awakening, as some kind of new Indian consciousness manifested itself in “a set of symbols and activities, often derived from plains cultures ”. S . Cornell, The Return of the Native: American Indian Political Resurgence, New York 1988, p . -

NAS 204 the Native American Experience

NAS 204 The Native American Experience Winter 20 Tuesday 6-9:20 pm JXJ 1311 Instructor Shirley Brozzo [email protected] Office: 3001 Hedgcock Cell 906-360-5406 NO calls after 10 pm Multicultural Ed & Res. Center Pronouns: she/her/hers Office phone: 906-227-1554 3 required texts Benton Banai, Eddie The Mishomis Book Child, Brenda editor Boarding School Seasons Lobo, Talbot, Morris Native American Voices, 3rd Edition Weekly Assignments: Have these pages read when you come to class each week Jan 14 Introduction, initial drawings, tribal listings, description of presentations Video: More Than Bows and Arrows 21 CULTURE AND CUSTOMS: Read the Mishomis Book 28 IDENTITY AND ORAL TRADITIONS: Read Native American Voices Part I: Introduction pages 2-9 Part I Ch 3: Indigenous Identity: What Is It, and Who Really Has It pgs 28-35 Part 1 short section: Native American Demographics pgs 45-47 Part 1 short section: The US Census pg 48 Part III: Introduction pgs 95-100 Part III Ch 1: 500 Years of Injustice… pgs 101-104 Part V Ch 3 But is It American Indian Art? Pgs 214-221 ECOLOGY AND LAND TRADITIONS Part III Ch 3: The Black Hills: Sacred Land of the Lakota... pgs 113-119 Part VII: Introduction pgs 308-309 Feb 4 Test # 1 100 points Video: American Outrage 11 BOARDING SCHOOLS: Read Boarding School Seasons Video: In the Whiteman's Image 18 MORE SCHOOLING: Read Native American Voices Part II Ch 5: Just Speak Your Language… pgs 90-92 Part VI Introduction, pgs 238-245 Part VI Ch 6: If We Get the Girls… pgs 284-291 Part VI Ch 7: Protagonism Emergent… pgs 292-300 -

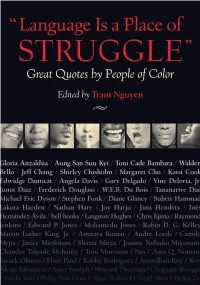

"Language Is a Place of Struggle" : Great Quotes by People of Color

“Language Is a Place of STRUGGLE” “Language Is a Place of STRUGGLE” Great Quotes by People of Color Edited by Tram Nguyen Beacon Press, Boston A complete list of quote sources for “Language Is a Place of Struggle” can be located at www.beacon.org/nguyen Beacon Press 25 Beacon Street Boston, Massachusetts 02108-2892 www.beacon.org Beacon Press books are published under the auspices of the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations. © 2009 by Tram Nguyen All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 12 11 10 09 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper that meets the uncoated paper ANSI/NISO specifications for permanence as revised in 1992. Text design by Susan E. Kelly at Wilsted & Taylor Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Language is a place of struggle : great quotes by people of color / edited by Tram Nguyen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8070-4800-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Minorities—United States—Quotations. 2. Immigrants—United States—Quotations. 3. United States—Race relations—Quotations, maxims, etc. 4. United States—Ethnic relations—Quotations, maxims, etc. 5. United States—Social conditions—Quotations, maxims, etc. 6. Social change—United States—Quotations, maxims, etc. 7. Community life—United States—Quotations, maxims, etc. 8. Social justice—United States— Quotations, maxims, etc. 9. Spirituality—Quotations, maxims, etc. I. Nguyen, Tram. E184.A1L259 2008 305.8—dc22 2008015487 Contents Foreword vii Chapter 1 Roots -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: SLAVE SHIPS, SHAMROCKS, AND SHACKLES: TRANSATLANTIC CONNECTIONS IN BLACK AMERICAN AND NORTHERN IRISH WOMEN’S REVOLUTIONARY AUTO/BIOGRAPHICAL WRITING, 1960S-1990S Amy L. Washburn, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Professor Deborah S. Rosenfelt Department of Women’s Studies This dissertation explores revolutionary women’s contributions to the anti-colonial civil rights movements of the United States and Northern Ireland from the late 1960s to the late 1990s. I connect the work of Black American and Northern Irish revolutionary women leaders/writers involved in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Black Panther Party (BPP), Black Liberation Army (BLA), the Republic for New Afrika (RNA), the Soledad Brothers’ Defense Committee, the Communist Party- USA (Che Lumumba Club), the Jericho Movement, People’s Democracy (PD), the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP), the National H-Block/ Armagh Committee, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), Women Against Imperialism (WAI), and/or Sinn Féin (SF), among others by examining their leadership roles, individual voices, and cultural productions. This project analyses political communiqués/ petitions, news coverage, prison files, personal letters, poetry and short prose, and memoirs of revolutionary Black American and Northern Irish women, all of whom were targeted, arrested, and imprisoned for their political activities. I highlight the personal correspondence, auto/biographical narratives, and poetry of the following key leaders/writers: Angela Y. Davis and Bernadette Devlin McAliskey; Assata Shakur and Margaretta D’Arcy; Ericka Huggins and Roseleen Walsh; Afeni Shakur-Davis, Joan Bird, Safiya Bukhari, and Martina Anderson, Ella O’Dwyer, and Mairéad Farrell. -

Comparative Cultures Lakota Woman

COMPARATIVE CULTURES LAKOTA WOMAN I have prepared some questions for you to answer as while reading Mary Brave Bird Crow Dog’s autobiography. This book is a personal account of the American Indian Movement from the point of view of those involved. *** At the end of each chapter, after answering my question in one paragraph, write another paragraph about what struck you most about the chapter. Give me your reaction and thoughts about what Mary has said. *** (So, I’m expecting two paragraphs for each chapter, about five to six pages total.) Chapter 1: What Indian nation does Mary belong to? Where is she from? Why is Mary prouder of her husband’s family than she is of her own? Chapter 2: What was one incident of racism Mary encountered growing up? Chapter 3: What does Mary say are the differences between traditional Lakota child-rearing and Indian schools? Why did Mary leave school? Chapter 4: Why did Mary begin drinking? What does she think causes the “Indian drinking problem?” Chapter 5: What was Mary’s life like as a teenager? How do you think you would have reacted under similar conditions? Chapter 6: Describe the Trail of Broken Treaties and the takeover of the BIA. Chapter 7: What is the significance of peyote in Indian religion? What does Mary think about non-Indian use of peyote? Chapter 8: Why did the Indians pick Wounded Knee to make a stand? How did Mary end up there? Chapter 9: What were conditions like during the siege at Wounded Knee? What was the government’s reaction to the occupation? Do you think the government overreacted? What could have the government done instead? Chapter 10: Why did Crow Dog revive the Ghost Dance? Describe the original Ghost Dance. -

He Uses of Humor in Native American and Chicano/A Cultures: an Alternative Study Of

The Uses of Humor in Native American and Chicano/a Cultures: An Alternative Study of Their Literature, Cinema, and Video Games Autora: Tamara Barreiro Neira Tese de doutoramento/ Tesis doctoral/ Doctoral Thesis UDC 2018 Directora e titora: Carolina Núñez Puente Programa de doutoramento en Estudos Ingleses Avanzados: Lingüística, Literatura e Cultura Table of contents Resumo .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Resumen ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Sinopsis ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 21 1. Humor and ethnic groups: nonviolent resistance ................................................................ 29 1.1. Exiles in their own land: Chicanos/as and Native Americans ..................................... 29 1.2. Humor: a weapon of mass creation ............................................................................. 37 1.3. Inter-Ethnic Studies: combining forces ...................................................................... -

Books for Brain Power Fiction

Books for Brain Power A.k.a. Traci's Über-Cool booklist Fiction Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri. A great collection of short stories that won a Pulitzer Prize, and it actually deserves it. These stories mainly compare and contrast the modern world with the echoes of India's politics and culture. (Short Stories) (Modern India) The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon. Fifteen-year- old Christopher John Francis Boone, raised in a working-class home by parents who can barely cope with their child's quirks, is mathematically gifted and socially hopeless. Late one night, Christopher comes across his neighbor's poodle, Wellington, impaled on a garden fork. Outraged, he decides to find the murderer. (Fiction) (Mystery) Life of Pi by Yann Martel. In his 16th year, Pi sets sail with his family and some of their menagerie to start a new life in Canada. Halfway to Midway Island, the ship sinks into the Pacific, leaving Pi stranded on a life raft with a hyena, an orangutan, an injured zebra, and a 450-pound Bengal tiger named Richard Parker. After the beast dispatches the others, Pi is left to survive for 227 days with his large feline companion on the 26- foot-long raft. He must use all his knowledge, wits, and faith to keep himself alive. (Fiction) The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini. This is the story of Amir, the privileged son of a wealthy businessman in Kabul, and Hassan, the son of Amir's father's servant. They spend idyllic days running kites and telling stories of mystical places and powerful warriors until an unspeakable event changes the nature of their relationship forever and eventually cements their bond in ways neither boy could have ever predicted. -

Contemporary Lakota Identity: Melda and Lupe Trejo on 'Being Indian'

CONTEMPORARY LAKOTA IDENTITY: MELDA AND LUPE TREJO ON 'BEING INDIAN' by LARISSA SUZANNE PETRILLO B.Sc, The University of Toronto, 1987 M.A., Wilfrid Laurier University, 1995 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Individual Interdisciplinary Studies Graduate Program. ) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA December 2001 © Larissa Suzanne Petrillo, 2001 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date DE-6 (2/88) Abstract This thesis explores contemporary Lakota identity, as informed by the life story narratives of Melda and Lupe Trejo. Melda Red Bear (Lakota) was born on Pine Ridge (Oglala Lakota / Sioux) Reservation in South Dakota (1939-). Her husband, Lupe Trejo (1938-1999) is Mexican and has been a long-term resident of the reservation. I first met this couple in 1994 and developed an abiding friendship with them prior to our decision to collaborate in recording their storytelling sessions (1997-98). The recording and interpretation of the material evokes ethical questions about power and representation that have arisen with debates about 'as-told-to' autobiographies. -

Nineteenthcentury Dramaturgy and a Twentieth-Century Passage from a History School Book

BOOK REVlBWS 99 nineteenthcentury dramaturgy and a twentieth-century passage from a history school book. The commentary explains that the event temporarily faded from memory under the auspices of Philip's grandson, Saint Louis, but re-emerged in the seventeenth-century when "a romantic taste for medievalism" develops (168). Duby shows that in the nineteenth century the event beczme "a manifestation of French patriotism" (173), and he concludes by confirming that, though the event may seem to be fading from memory in the face of a united Europe, the implications of battling with God on one's side linger (179). Duby writes that "Bouvines had to be celebrated; its lesson had to be learnt" (171), and with this masterful work, he accomplishes both feats. Rendered accessible in English by Tihanyi's translation, Duby's The Legend of Bouvines thoroughly depicts a significant event of the Middle Ages. In addition to creating a valuable tool for historians, Duby entices folklorists and those interested in medieval culture by situating the event in a cultural context and tracing its lingering memory. Paul Graham McHenry. Adobe and Rammed Earth Buildings: Design and Construction. Tuscon: University of Arizona Press, 1984. Pp. vii + 217, black-and-white photos, illustrations, appendices, index. $24.95 paper. Andy Knote Indiana University Paul McHenry is regarded as one of the world authorities on adobe construction. This is the second of his books on the subject. His first book, Adobe: Build It Yourself, as the title indicates, approaches the subject primarily from the perspective of those who are interested in building, and the information contained in the book is limited with that end in mind. -

Books with Powerful Messages of Social Change Social Analysis Issues

Books with Powerful Messages of Social Change Non-Fiction The journeys of people who navigate social barriers Fiction A deepening understanding of the human experience and society Social Analysis Issues, activism, and visions for social change Yolanda C. Padilla Social Analysis This biography explores Alice Walker’s life experiences and her lifework in context of her philosophical thought, and celebrates the author’s creative genius and heroism. It represents the only biography that offers a philosophical examination of this deeply philosophical artist- activist. SOCIAL ANALYSIS Throughout her career as a Texas senator, U.S. congresswoman, and distinguished professor at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, Barbara Jordan lived by a simple creed: "Ethical behavior means being honest, telling the truth, and doing what you said you were going to do." Her strong stand for ethics in government, civil liberties, and democratic values still provides a standard around which the nation can unite in the twenty-first century. This volume brings together several major political speeches that articulate Barbara Jordan's most deeply held values. SOCIAL ANALYSIS Susan Burton's world changed in an instant when her five-year-old son was killed by a van driving down their street. Consumed by grief and without access to professional help, Susan self-medicated, becoming addicted first to cocaine then to crack. As a resident of South Los Angeles, a black community under siege in the War on Drugs, it was but a matter of time before Susan was arrested. She cycled in and out of prison for over 15 years; never was she offered therapy or treatment for addiction. -

South Dakota History

VOL. 41, NO. 1 SPRING 2011 South Dakota History 1 Index to South Dakota History, Volumes 1–40 (1970–2010) COMPILED BY RODGER HARTLEY Copyright 2011 by the South Dakota State Historical Society, Pierre, S.Dak. 57501-2217 ISSN 0361-8676 USER’S GUIDE Over the past forty years, each volume (four issues) of South Dakota History has carried its own index. From 1970 to 1994, these indexes were printed separately upon comple- tion of the last issue for the year. If not bound with the volume, as in a library set, they were easily misplaced or lost. As the journal approached its twenty-fifth year of publica- tion, the editors decided to integrate future indexes into the back of every final issue for the volume, a practice that began with Volume 26. To mark the milestone anniversary in 1995, they combined the indexes produced up until that time to create a twenty-five-year cumulative index. As the journal’s fortieth anniversary year of 2010 approached, the need for another compilation became clear. The index presented here integrates the past fifteen volume indexes into the earlier twenty-five-year cumulative index. While indexers’ styles and skills have varied over the years, every effort has been made to create a product that is as complete and consistent as possible. Throughout the index, volume numbers appear in bold-face type, while page numbers are in book-face. Within the larger entries, references to brief or isolated pas- sages are listed at the beginning, while more extensive references are grouped under the subheadings that follow. -

Literature of the American West

LITERATURE OF THE AMERICAN WEST A CULTURAL APPROACH SUB GOttingen 217 188 850 2004 A 1752 Greg Lyons Central Oregon Community College New York San Francisco Boston London Toronto Sydney Tokyo Singapore Madrid Mexico City Munich Paris Cape Town Hong Kong Montreal CONTENTS Preface vii Acknowledgments x Introduction xi PART ONE FOUNDATIONS FOR A WESTERN MYTHOLOGY 1 CHAPTER 1 Mapping the Terrain 3 INTRODUCTION 3 EMMANUEL LEUTZE Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way (1861) 6 HECTOR ST. JOHN DE CREVECOEUR from "What Is an American?" from Letters from an American Farmer (1782) 7 FREDERICK JACKSON TURNER "The Significance of the Frontier in American History" (1893) 12 . MERIWETHER LEWIS AND WILLIAM CLARK from Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804-1806 (1905) 19 BRETHARTE "The Outcasts of Poker Flat" (1869) 31 Focus ON FILM John Ford (director), Stagecoach (1939) 42 TOPICS FOR RESEARCH AND WRITING 43 iv CONTENTS CHAPTER 2 Crossing Frontiers 45 INTRODUCTION 45 GEORGE CATLIN Buffalo Bull's Backfat, Head Chief, Blood Tribe (1832) 50 LEWIS HECTOR GARRARD "The Village" from Wah-to-Yah and the Taos Trail (1850) 51 KARL BODMER Bison Dance of the Mandan Indians in Front of Their Medicine Lodge (1836) 58 EDWARD ELLIS from Seth Jones; or, The Captives of the Frontier (1860) 59 GEORGE CALEB BINGHAM The Concealed Enemy (1845) 73 A. B. GUTHRIE, JR. "Mountain Medicine" (1947) 73 WILLIAM TYLEE RANNEY Advice on the Prairie (1853) 85 Focus ON FILM Elliot Silverstein (director), A Man Called Horse (1970) 86 TOPICS FOR RESEARCH AND WRITING 86 CHAPTER 3 Working the Land 89 INTRODUCTION .