Manuscript Heritage on Astronomy Samīkṣikā - 12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rationale of the Chakravala Process of Jayadeva and Bhaskara Ii

HISTORIA MATHEMATICA 2 (1975) , 167-184 RATIONALE OF THE CHAKRAVALA PROCESS OF JAYADEVA AND BHASKARA II BY CLAS-OLOF SELENIUS UNIVERSITY OF UPPSALA SUMMARIES The old Indian chakravala method for solving the Bhaskara-Pell equation or varga-prakrti x 2- Dy 2 = 1 is investigated and explained in detail. Previous mis- conceptions are corrected, for example that chakravgla, the short cut method bhavana included, corresponds to the quick-method of Fermat. The chakravala process corresponds to a half-regular best approximating algorithm of minimal length which has several deep minimization properties. The periodically appearing quantities (jyestha-mfila, kanistha-mfila, ksepaka, kuttak~ra, etc.) are correctly understood only with the new theory. Den fornindiska metoden cakravala att l~sa Bhaskara- Pell-ekvationen eller varga-prakrti x 2 - Dy 2 = 1 detaljunders~ks och f~rklaras h~r. Tidigare missuppfatt- 0 ningar r~ttas, sasom att cakravala, genv~gsmetoden bhavana inbegripen, motsvarade Fermats snabbmetod. Cakravalaprocessen motsvarar en halvregelbunden b~st- approximerande algoritm av minimal l~ngd med flera djupt liggande minimeringsegenskaper. De periodvis upptr~dande storheterna (jyestha-m~la, kanistha-mula, ksepaka, kuttakara, os~) blir forstaellga0. 0 . f~rst genom den nya teorin. Die alte indische Methode cakrav~la zur Lbsung der Bhaskara-Pell-Gleichung oder varga-prakrti x 2 - Dy 2 = 1 wird hier im einzelnen untersucht und erkl~rt. Fr~here Missverst~ndnisse werden aufgekl~rt, z.B. dass cakrav~la, einschliesslich der Richtwegmethode bhavana, der Fermat- schen Schnellmethode entspreche. Der cakravala-Prozess entspricht einem halbregelm~ssigen bestapproximierenden Algorithmus von minimaler L~nge und mit mehreren tief- liegenden Minimierungseigenschaften. Die periodisch auftretenden Quantit~ten (jyestha-mfila, kanistha-mfila, ksepaka, kuttak~ra, usw.) werden erst durch die neue Theorie verst~ndlich. -

Bhaskara's Approximation to and Madhava's Series for Sine

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Transforming Instruction in Undergraduate Calculus Mathematics via Primary Historical Sources (TRIUMPHS) Winter 2020 Bhaskara's Approximation to and Madhava's Series for Sine Kenneth M. Monks [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/triumphs_calculus Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Monks, Kenneth M., "Bhaskara's Approximation to and Madhava's Series for Sine" (2020). Calculus. 15. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/triumphs_calculus/15 This Course Materials is brought to you for free and open access by the Transforming Instruction in Undergraduate Mathematics via Primary Historical Sources (TRIUMPHS) at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Calculus by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bh¯askara's Approximation to and M¯adhava's Series for Sine Kenneth M Monks∗ May 20, 2021 A chord is a very natural construction in geometry; it is the line segment obtained by connecting two points on a circle. Chords were studied extensively in ancient Greek geometry. For example, Euclid's Elements [Euclid, c. 300 BCE] contains plenty of theorems relating the circle's arc AB to the line segment AB (shown below).1 A B Indian mathematicians, motivated by astronomy, were the first to specifically calculate values of half-chords instead [Gupta, 1967, p. 121]. This work led very directly to the function which we call sine today. Task 1 Half-chords and sine. Suppose the circle above has radius 1. -

Crowdsourcing

CROWDSOURCING The establishment of the ZerOrigIndia Foundation is predicated on a single premise, namely, that our decades-long studies indicate that there are sound reasons to assume that facilitating further independent scientific research into the origin of the zero digit as numeral may lead to theoretical insights and practical innovations equal to or perhaps even exceeding the revolutionary progress to which the historic emergence of the zero digit in India somewhere between 200 BCE and 500 CE has led across the planet, in the fields of mathematics, science and technology since its first emergence. No one to date can doubt the astounding utility of the tenth and last digit to complete the decimal system, yet the origin of the zero digit is shrouded in mystery to this day. It is high time, therefore, that a systematic and concerted effort is undertaken by a multidisciplinary team of experts to unearth any extant evidence bearing on the origin of the zero digit in India. The ZerOrigIndia Foundation is intended to serve as instrument to collect the requisite funds to finance said independent scientific research in a timely and effective manner. Research Academics and researchers worldwide are invited to join our efforts to unearth any extant evidence of the zero digit in India. The ZerOrigIndia Foundation will facilitate the research in various ways, chief among which is to engage in fundraising to finance projects related to our objective. Academics and researchers associated with reputed institutions of higher learning are invited to monitor progress reported by ZerOrigIndia Foundation, make suggestions and/or propose their own research projects to achieve the avowed aim. -

Aryabhatiya with English Commentary

ARYABHATIYA OF ARYABHATA Critically edited with Introduction, English Translation. Notes, Comments and Indexes By KRIPA SHANKAR SHUKLA Deptt. of Mathematics and Astronomy University of Lucknow in collaboration with K. V. SARMA Studies V. V. B. Institute of Sanskrit and Indological Panjab University INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY NEW DELHI 1 Published for THE NATIONAL COMMISSION FOR THE COMPILATION OF HISTORY OF SCIENCES IN INDIA by The Indian National Science Academy Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi— © Indian National Science Academy 1976 Rs. 21.50 (in India) $ 7.00 ; £ 2.75 (outside India) EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Chairman : F. C. Auluck Secretary : B. V. Subbarayappa Member : R. S. Sharma Editors : K. S. Shukla and K. V. Sarma Printed in India At the Vishveshvaranand Vedic Research Institute Press Sadhu Ashram, Hosbiarpur (Pb.) CONTENTS Page FOREWORD iii INTRODUCTION xvii 1. Aryabhata— The author xvii 2. His place xvii 1. Kusumapura xvii 2. Asmaka xix 3. His time xix 4. His pupils xxii 5. Aryabhata's works xxiii 6. The Aryabhatiya xxiii 1. Its contents xxiii 2. A collection of two compositions xxv 3. A work of the Brahma school xxvi 4. Its notable features xxvii 1. The alphabetical system of numeral notation xxvii 2. Circumference-diameter ratio, viz., tz xxviii table of sine-differences xxviii . 3. The 4. Formula for sin 0, when 6>rc/2 xxviii 5. Solution of indeterminate equations xxviii 6. Theory of the Earth's rotation xxix 7. The astronomical parameters xxix 8. Time and divisions of time xxix 9. Theory of planetary motion xxxi - 10. Innovations in planetary computation xxxiii 11. -

Kamala¯Kara Commentary on the Work, Called Tattvavivekodāharan

K related to the Siddhānta-Tattvaviveka, one a regular Kamala¯kara commentary on the work, called Tattvavivekodāharan. a, and the other a supplement to that work, called Śes.āvasanā, in which he supplied elucidations and new K. V. SARMA material for a proper understanding of his main work. He held the Sūryasiddhānta in great esteem and also wrote a Kamalākara was one of the most erudite and forward- commentary on that work. looking Indian astronomers who flourished in Varanasi Kamalākara was a critic of Bhāskara and his during the seventeenth century. Belonging to Mahar- Siddhāntaśiroman. i, and an arch-rival of Munīśvara, a ashtrian stock, and born in about 1610, Kamalākara close follower of Bhāskara. This rivalry erupted into came from a long unbroken line of astronomers, bitter critiques on the astronomical front. Thus Ranga- originally settled at the village of Godā on the northern nātha, younger brother of Kamalākara, wrote, at the . banks of the river Godāvarī. Towards AD 1500, the insistence of the latter, a critique on Munīśvara’s Bhangī family migrated to Varanasi and came to be regarded as method (winding method) of true planets, entitled . reputed astronomers and astrologers. Kamalākara Bhangī-vibhangī (Defacement of the Bhangi), to which . studied traditional Hindu astronomy under his elder Munīśvara replied with a Khand.ana (Counter). Munīś- brother Divākara, but extended the range of his studies vara attacked the theory of precession advocated by to Islamic astronomy, particularly to the school of Kamalākara, and Ranganātha refuted the criticisms of his Ulugh Beg of Samarkand. He also studied Greek brother in his Loha-gola-khan. -

A Study on the Encoding Systems in Vedic Era and Modern Era 1K

International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics Volume 114 No. 7 2017, 425-433 ISSN: 1311-8080 (printed version); ISSN: 1314-3395 (on-line version) url: http://www.ijpam.eu Special Issue ijpam.eu A Study on the Encoding Systems in Vedic Era and Modern Era 1K. Lakshmi Priya and 2R. Parameswaran 1Department of Mathematics, School of Arts and Sciences, Amrita University, Kochi. [email protected] 2Department of Mathematics, School of Arts and Sciences, Amrita University, Kochi. [email protected] Abstract Encoding is the action of transferring a message in to codes. In this paper I present a study on the encoding systems in vedic era and modern era. The Sanskrit verses written in the vedic era are not just the praises of the Gods they are also numerical codes. In ancient India there were three means of recording numerals in Sanskrit words which are Katapayadi system, Bhutasamkhya system and Aryabhata numeration. These systems were used by many ancient mathematicians in India. In this paper the Katapayadi system used in vedic times is applied to modern ciphers– Vigenere Cipher and Affine Cipher. Key Words:Katapayadi system, vigenere cipher, affine cipher. 425 International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics Special Issue 1. Introduction Encoding is the process of transforming messages into an arrangement required for data transmission, storage and compression/decompression. In cryptography, encryption is the method of transforming information using an algorithm to make it illegible to anyone except those owning special information, usually called as a key. In vedic era, Sanskrit is the language used. It is supposed to be the ancient language, from which most of the modern dialects are developed. -

BOOK REVIEW a PASSAGE to INFINITY: Medieval Indian Mathematics from Kerala and Its Impact, by George Gheverghese Joseph, Sage Pu

HARDY-RAMANUJAN JOURNAL 36 (2013), 43-46 BOOK REVIEW A PASSAGE TO INFINITY: Medieval Indian Mathematics from Kerala and its impact, by George Gheverghese Joseph, Sage Publications India Private Limited, 2009, 220p. With bibliography and index. ISBN 978-81-321-0168-0. Reviewed by M. Ram Murty, Queen's University. It is well-known that the profound concept of zero as a mathematical notion orig- inates in India. However, it is not so well-known that infinity as a mathematical concept also has its birth in India and we may largely credit the Kerala school of mathematics for its discovery. The book under review chronicles the evolution of this epoch making idea of the Kerala school in the 14th century and afterwards. Here is a short summary of the contents. After a brief introduction, chapters 2 and 3 deal with the social and mathematical origins of the Kerala school. The main mathematical contributions are discussed in the subsequent chapters with chapter 6 being devoted to Madhava's work and chapter 7 dealing with the power series for the sine and cosine function as developed by the Kerala school. The final chapters speculate on how some of these ideas may have travelled to Europe (via Jesuit mis- sionaries) well before the work of Newton and Leibniz. It is argued that just as the number system travelled from India to Arabia and then to Europe, similarly many of these concepts may have travelled as methods for computational expediency rather than the abstract concepts on which these algorithms were founded. Large numbers make their first appearance in the ancient writings like the Rig Veda and the Upanishads. -

31 Indian Mathematicians

Indian Mathematician 1. Baudhayana (800BC) Baudhayana was the first great geometrician of the Vedic altars. The science of geometry originated in India in connection with the construction of the altars of the Vedic sacrifices. These sacrifices were performed at certain precalculated time, and were of particular sizes and shapes. The expert of sacrifices needed knowledge of astronomy to calculate the time, and the knowledge of geometry to measure distance, area and volume to make altars. Strict texts and scriptures in the form of manuals known as Sulba Sutras were followed for performing such sacrifices. Bandhayana's Sulba Sutra was the biggest and oldest among many Sulbas followed during olden times. Which gave proof of many geometrical formulae including Pythagorean theorem 2. Āryabhaṭa(476CE-550 CE) Aryabhata mentions in the Aryabhatiya that it was composed 3,600 years into the Kali Yuga, when he was 23 years old. This corresponds to 499 CE, and implies that he was born in 476. Aryabhata called himself a native of Kusumapura or Pataliputra (present day Patna, Bihar). Notabl e Āryabhaṭīya, Arya-siddhanta works Explanation of lunar eclipse and solar eclipse, rotation of Earth on its axis, Notabl reflection of light by moon, sinusoidal functions, solution of single e variable quadratic equation, value of π correct to 4 decimal places, ideas circumference of Earth to 99.8% accuracy, calculation of the length of sidereal year 3. Varahamihira (505-587AD) Varaha or Mihir, was an Indian astronomer, mathematician, and astrologer who lived in Ujjain. He was born in Avanti (India) region, roughly corresponding to modern-day Malwa, to Adityadasa, who was himself an astronomer. -

Global Positioning System (GPS)

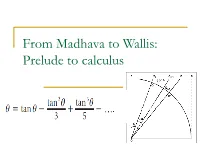

From Madhava to Wallis: Prelude to calculus Madhava and the Kerala school There is now considerable documentary evidence that many of the ideas needed for the development of calculus were already written down by what is now called the Kerala school of mathematics in south western India in the 14th century. Madhava (1340-1425 CE) was the foremost member of this school who developed the theory of the trigonometric functions and derived the familiar Taylor series expansions for them. His work was described in detail with proofs by Jyesthadeva who wrote the text called Yuktibhasha in the middle of the 16th century. Madhava series for the trigonometric functions Studying the sine and cosine function, Madhava derived the following well-known formulas: The last is the famous arctan series re-discovered by Gregory several centuries later. When θ=π/4, we get the famous Madhava-Gregory-Leibniz series for π. The series for arctan x Evaluation of the sum The migration of ideas and Father Mersenne According to George Joseph, author of the Crest of the Peacock, it is quite possible that many of the ideas of the Kerala school migrated through Jesuit missionaries to Europe. Most notable among the Jesuits was Father Marin Mersenne (1588-1648) who was a close friend of both Descartes and Fermat (in fact, many conjectures attributed to Fermat appear in his letters to Mersenne). Thus many of the ideas of calculus were “in the air”. The work of Cavalieri, Fermat, Mengoli and Gregory Mengoli and log 2 Mengoli discovered that 1-1/2 + 1/3 -1/4 + … converges to log 2. -

Equation Solving in Indian Mathematics

U.U.D.M. Project Report 2018:27 Equation Solving in Indian Mathematics Rania Al Homsi Examensarbete i matematik, 15 hp Handledare: Veronica Crispin Quinonez Examinator: Martin Herschend Juni 2018 Department of Mathematics Uppsala University Equation Solving in Indian Mathematics Rania Al Homsi “We owe a lot to the ancient Indians teaching us how to count. Without which most modern scientific discoveries would have been impossible” Albert Einstein Sammanfattning Matematik i antika och medeltida Indien har påverkat utvecklingen av modern matematik signifi- kant. Vissa människor vet de matematiska prestationer som har sitt urspring i Indien och har haft djupgående inverkan på matematiska världen, medan andra gör det inte. Ekvationer var ett av de områden som indiska lärda var mycket intresserade av. Vad är de viktigaste indiska bidrag i mate- matik? Hur kunde de indiska matematikerna lösa matematiska problem samt ekvationer? Indiska matematiker uppfann geniala metoder för att hitta lösningar för ekvationer av första graden med en eller flera okända. De studerade också ekvationer av andra graden och hittade heltalslösningar för dem. Denna uppsats presenterar en litteraturstudie om indisk matematik. Den ger en kort översyn om ma- tematikens historia i Indien under många hundra år och handlar om de olika indiska metoderna för att lösa olika typer av ekvationer. Uppsatsen kommer att delas in i fyra avsnitt: 1) Kvadratisk och kubisk extraktion av Aryabhata 2) Kuttaka av Aryabhata för att lösa den linjära ekvationen på formen 푐 = 푎푥 + 푏푦 3) Bhavana-metoden av Brahmagupta för att lösa kvadratisk ekvation på formen 퐷푥2 + 1 = 푦2 4) Chakravala-metoden som är en annan metod av Bhaskara och Jayadeva för att lösa kvadratisk ekvation 퐷푥2 + 1 = 푦2. -

From Jantar-Mantar to Kavalur

Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers of India: RN.70269/98 ISSN: 0972-169X Monthly Newsletter of Vigyan Prasar December 15, 1999 Vol. 2 No.3 VP News Inside SCIENCE VIDEOS FROM VIGYAN PRASAR Coverage of science in Indian mass media, especially television, has been very poor. One reason, often heard in media circles, is the absence of a Editorial mechanism to cover stories of latest R&D developments from the science and technology institutions in the country. To bridge the gap between Mass media and R&D institutions, Vigyan Prasar has recently launched a science video Prasanta Chandra feature service on experimental basis. Mahalanobis Six feature stories have been produced last month. Three features on National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources and three on latest developments from the National Physical Laboratory, New Delhi. The feature stories cover From Jantar-Mantar the profile of the largest gene bank in the world - the NBPGR, various Ex-situ techniques to conserve seeds and a report on the plant quarantine division. to Kavalur The stories from NPL cover the 'Teleclock' service to transmit Time Data digitally through a telephone line, the SODAR - Sound Detection and flanging technique for air pollution management and the piezoelectric Accelerometer The Story of Wool PL-810 to measure vibrations. R&D organizations may write to us for covering interesting Research and Development works happening in their laboratories. Delhi's Water and Solid Waste Management: Emerging Scenario Vigyan Prasar has launched a series on India's Environmental Hotspots. The latest publication in this series is on Delhi's water and waste management scenario. -

Chapter Two Astrological Works in Sanskrit

51 CHAPTER TWO ASTROLOGICAL WORKS IN SANSKRIT Astrology can be defined as the 'philosophy of discovery' which analyzing past impulses and future actions of both individuals and communities in the light of planetary configurations. Astrology explains life's reaction to planetary movements. In Sanskrit it is called hora sastra the science of time-'^rwRH ^5R5fai«fH5iref ^ ^Tm ^ ^ % ^i^J' 11 L.R. Chawdhary documented the use of astrology as "astrology is important to male or female as is the case of psychology, this branch of knowledge deals with the human soul deriving awareness of the mind from the careful examination of the facts of consciousness. Astrology complements everything in psychology because it explains the facts of planetary influences on the conscious and subconscious providing a guideline towards all aspects of life, harmony of mind, body and spirit. This is the real use of astrology^. Dr. ^.V.Raman implies that "astrology in India is a part of the whole of Indian culture and plays an integral part in guiding life for all at all stages of life" ^. Predictive astrology is a part of astronomy that exists by the influence of ganita and astronomical doctrines. Winternitz observes that an astrologer is required to possess all possible noble quantities and a comprehensive knowledge of astronomy, ' Quoted from Sabdakalpadruma, kanta-ll, p.550 ^ L.R.Chawdhari, Secrets of astrology. Sterling Paper backs, New Delhi,1998, p.3 ^Raman.B.V, Planetary influence of Human affairs, U.B.S. Publishers, New Delhi, 1996,p.147 52 mathematics and astrology^ Astrology or predictive astrology is said to be coconnected with 'astronomy'.