Bhaskara's Approximation to and Madhava's Series for Sine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kamala¯Kara Commentary on the Work, Called Tattvavivekodāharan

K related to the Siddhānta-Tattvaviveka, one a regular Kamala¯kara commentary on the work, called Tattvavivekodāharan. a, and the other a supplement to that work, called Śes.āvasanā, in which he supplied elucidations and new K. V. SARMA material for a proper understanding of his main work. He held the Sūryasiddhānta in great esteem and also wrote a Kamalākara was one of the most erudite and forward- commentary on that work. looking Indian astronomers who flourished in Varanasi Kamalākara was a critic of Bhāskara and his during the seventeenth century. Belonging to Mahar- Siddhāntaśiroman. i, and an arch-rival of Munīśvara, a ashtrian stock, and born in about 1610, Kamalākara close follower of Bhāskara. This rivalry erupted into came from a long unbroken line of astronomers, bitter critiques on the astronomical front. Thus Ranga- originally settled at the village of Godā on the northern nātha, younger brother of Kamalākara, wrote, at the . banks of the river Godāvarī. Towards AD 1500, the insistence of the latter, a critique on Munīśvara’s Bhangī family migrated to Varanasi and came to be regarded as method (winding method) of true planets, entitled . reputed astronomers and astrologers. Kamalākara Bhangī-vibhangī (Defacement of the Bhangi), to which . studied traditional Hindu astronomy under his elder Munīśvara replied with a Khand.ana (Counter). Munīś- brother Divākara, but extended the range of his studies vara attacked the theory of precession advocated by to Islamic astronomy, particularly to the school of Kamalākara, and Ranganātha refuted the criticisms of his Ulugh Beg of Samarkand. He also studied Greek brother in his Loha-gola-khan. -

BOOK REVIEW a PASSAGE to INFINITY: Medieval Indian Mathematics from Kerala and Its Impact, by George Gheverghese Joseph, Sage Pu

HARDY-RAMANUJAN JOURNAL 36 (2013), 43-46 BOOK REVIEW A PASSAGE TO INFINITY: Medieval Indian Mathematics from Kerala and its impact, by George Gheverghese Joseph, Sage Publications India Private Limited, 2009, 220p. With bibliography and index. ISBN 978-81-321-0168-0. Reviewed by M. Ram Murty, Queen's University. It is well-known that the profound concept of zero as a mathematical notion orig- inates in India. However, it is not so well-known that infinity as a mathematical concept also has its birth in India and we may largely credit the Kerala school of mathematics for its discovery. The book under review chronicles the evolution of this epoch making idea of the Kerala school in the 14th century and afterwards. Here is a short summary of the contents. After a brief introduction, chapters 2 and 3 deal with the social and mathematical origins of the Kerala school. The main mathematical contributions are discussed in the subsequent chapters with chapter 6 being devoted to Madhava's work and chapter 7 dealing with the power series for the sine and cosine function as developed by the Kerala school. The final chapters speculate on how some of these ideas may have travelled to Europe (via Jesuit mis- sionaries) well before the work of Newton and Leibniz. It is argued that just as the number system travelled from India to Arabia and then to Europe, similarly many of these concepts may have travelled as methods for computational expediency rather than the abstract concepts on which these algorithms were founded. Large numbers make their first appearance in the ancient writings like the Rig Veda and the Upanishads. -

Global Positioning System (GPS)

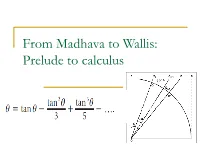

From Madhava to Wallis: Prelude to calculus Madhava and the Kerala school There is now considerable documentary evidence that many of the ideas needed for the development of calculus were already written down by what is now called the Kerala school of mathematics in south western India in the 14th century. Madhava (1340-1425 CE) was the foremost member of this school who developed the theory of the trigonometric functions and derived the familiar Taylor series expansions for them. His work was described in detail with proofs by Jyesthadeva who wrote the text called Yuktibhasha in the middle of the 16th century. Madhava series for the trigonometric functions Studying the sine and cosine function, Madhava derived the following well-known formulas: The last is the famous arctan series re-discovered by Gregory several centuries later. When θ=π/4, we get the famous Madhava-Gregory-Leibniz series for π. The series for arctan x Evaluation of the sum The migration of ideas and Father Mersenne According to George Joseph, author of the Crest of the Peacock, it is quite possible that many of the ideas of the Kerala school migrated through Jesuit missionaries to Europe. Most notable among the Jesuits was Father Marin Mersenne (1588-1648) who was a close friend of both Descartes and Fermat (in fact, many conjectures attributed to Fermat appear in his letters to Mersenne). Thus many of the ideas of calculus were “in the air”. The work of Cavalieri, Fermat, Mengoli and Gregory Mengoli and log 2 Mengoli discovered that 1-1/2 + 1/3 -1/4 + … converges to log 2. -

Approximation of Alternating Series Using Correction Function and Error Function

International Journal of Scientific and Innovative Mathematical Research (IJSIMR) Volume 4, Issue 8, August 2016, PP 24-26 ISSN 2347-307X (Print) & ISSN 2347-3142 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2347-3142.0408004 www.arcjournals.org Approximation of Alternating Series using Correction Function and Error Function Kumari Sreeja S Nair Dr.V.Madhukar Mallayya Assistant Professor of Mathematics Former Professor and Head Govt.Arts College, Thiruvananthapuram, Department of Mathematics Kerala, India Mar Ivanios College Thiruvananthapuram, India Abstract: In this paper we give a rational approximation of an alternating series using remainder term of the series. For that we shall introduce a correction function to the series. The correction function plays a vital role in series approximation. Using correction function we shall deduce an error function to the series. Keywords: Correction function, error function, remainder term, alternating series, Madhava series, rational approximation. 1. INTRODUCTION In 14푡ℎ century, the Indian mathematician Madhava gave an approximation of the pi series using remainder term of the series. Madhava series is, 4푑 4푑 4푑 ..................... 푛−1 4푑 푛 4푑(2푛)/2 C = − + − +(−1) + (−1) , where C is the circumference of a 1 3 5 2푛−1 2푛 2+1 (2푛)/2 circle of diameter d. Here the remainder term is (-1)n 4d G where G = is the correction n n 2푛 2+1 function. The introduction of the correction term gives a better approximation of the series. 2. METHOD 푛−1 ∞ (−1) APPROXIMATION OF THE ALTERNATING SERIES 푛=1 푛 푛+1 (푛+2) (−1)푛−1 The alternating series ∞ satisfies the conditions of alternating series test and so it is 푛=1 푛 푛+1 (푛+2) convergent. -

JETIR Research Journal

© 2020 JETIR November 2020, Volume 7, Issue 11 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Exploring the Algebraic and Geometric Nature of 흅. 1*Archisman Roy, 2Tushar Banerjee 1Author (Student), AOSHS, Higher Secondary School of Science; 2Research Scholar, SSSUTMS 1Department of Science, 2Department of Zoology 1Asansol, India. * denotes correspondence Abstract: This bodacious study has been endeavored to probe different natures of π. Π comes from the Greek script of the word ‘periphery’ which means circumference. In connection to that π has a birthright for claiming geometry as its origin. Metaphorically, it is a real and definite number which is algebraically inexpressible. Our piece of research is thus willing to persuade that every geometric relation can be expressed with some equations of algebra and each algebraic expansion has its geometric interpretation. In addition to that, the article produces numerously validated as well as cited works of famous mathematicians to cajole about the article's plausibility. It approaches a good deal of mathematical history for congenially maintaining its engagement with the content. Sufficient statistical data have been produced to sway every bit of the mathematical perspective. The piece of writing consists of suitable graphs and images adhering to its requirement. Furthermore, it expresses enthusiastically about its new substantial contribution regarding the cognizance of π. Finally, the article suffers a lenient way of producing π subsequently through three stages of visualizing a mathematical paradox viz geometric background, augmentation of algebra, and the real connection between them both. Index Terms - Irrational, constant, transcendental, infinite-fraction, exact. I. INTRODUCTION The world of algebraical mathematics especially the number theorems are gigantically fascinated by a few irrational numbers such as Euler's constant 'e' and the 'π'. -

Introduction to Scientific Computing

Introduction to Scientific Computing with Maple Programming Zhonggang Zeng c 2009 with contributions from David Rutschman August 23, 2015 Contents Table of Contents i Scientific Computing Index iv 1 Fundamentals 1 1.1 Maplecommandlines............................... 2 1.2 Simpleprogramming ............................... 10 1.3 Conditionalstatements-Branching . .. 18 1.4 Commonerrors .................................. 23 1.5 WritingaprojectreportonaMapleworksheet . ... 24 1.6 Exercises...................................... 24 1.7 Projects ...................................... 30 2 Loops. Part I 33 2.1 The“for-do”loop................................. 33 2.2 Iteration...................................... 35 2.2.1 Newton’s iteration (Numerical Analysis ) ................. 37 2.2.2 Chaotic map (Dynamic System ) ...................... 38 2.2.3 Continuous fractions (Number Theory ) .................. 39 2.2.4 Continuous fractions, revisited . 40 2.3 Recursivesummation............................... 41 2.3.1 Taylor series (Approximation Theory ) ................... 42 2.3.2 Quadrature (Numerical Analysis ) ..................... 44 2.3.3 Nested sums and products (Elementary Algebra ) ............ 45 2.4 Exploring scientific computing . 47 2.4.1 Fourier series (Fourier Analysis ) ..................... 47 2.4.2 Solving congruences (Number Theory ) ................... 48 2.5 Exercise ...................................... 49 2.6 Projects ...................................... 58 3 Loops. Part II 61 3.1 The“while-do”loop .............................. -

Rapidly Convergent Series from Gregory Series 1

International J. of Math. Sci. & Engg. Appls. (IJMSEA) ISSN 0973-9424, Vol. 11 No. I (April, 2017), pp. 171-175 RAPIDLY CONVERGENT SERIES FROM GREGORY SERIES KUMARI SREEJA S. NAIR1 AND Dr. MARY GEORGE2 1 Assistant Professor of Mathematics, Govt.Arts College, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India 2 Associative Professor and Head, Department of Mathematics, Mar Ivanios College, Thiruvananthapuram, India Abstract In this paper we shall extract a rapidly convergent series from a given series, by applying a correction function to the series. Hence the rate of convergence of the new series can be increased. 1. Introduction The approximation of an alternating series can be done using remainder term of the series. The absolute value of the remainder term is the correction function. The in- troduction of correction function certainly improves the sum of the series and gives a better approximation for it. We can also deduce some rapidly convergent series using correction function and the corresponding error functions. The new series so extracted increases the rate of convergence of the series. −−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−− Key Words : Remainder term, Alternating series, Madhava series, Rate of convergence, Rapidly convergent series. c http: //www.ascent-journals.com 171 172 KUMARI SREEJA S. NAIR & Dr. MARY GEORGE 2. Preliminary Definitions 1 P n−1 Definition 1 : An alternating series is an infinite series of the form (−) an where n=1 the terms an > 0: 1 P n−1 Definition 2 : The remainder term for an alternating series (−) an is the sum n=1 of the series after n terms. It is denoted by Rn. 1 P k−1 i.e. -

Sources in the Development of Mathematics

This page intentionally left blank Sources in the Development of Mathematics The discovery of infinite products by Wallis and infinite series by Newton marked the beginning of the modern mathematical era. The use of series allowed Newton to find the area under a curve defined by any algebraic equation, an achievement completely beyond the earlier methods of Torricelli, Fermat, and Pascal. The work of Newton and his contemporaries, including Leibniz and the Bernoullis, was concentrated in math- ematical analysis and physics. Euler’s prodigious mathematical accomplishments dramatically extended the scope of series and products to algebra, combinatorics, and number theory. Series and products proved pivotal in the work of Gauss, Abel, and Jacobi in elliptic functions; in Boole and Lagrange’s operator calculus; and in Cayley, Sylvester, and Hilbert’s invariant theory. Series and products still play a critical role in the mathematics of today. Consider the conjectures of Langlands, including that of Shimura-Taniyama, leading to Wiles’s proof of Fermat’s last theorem. Drawing on the original work of mathematicians from Europe, Asia, and America, Ranjan Roy discusses many facets of the discovery and use of infinite series and products. He gives context and motivation for these discoveries, including original notation and diagrams when practical. He presents multiple derivations for many important theorems and formulas and provides interesting exercises, supplementing the results of each chapter. Roy deals with numerous results, theorems, and methods used by students, mathematicians, engineers, and physicists. Moreover, since he presents original math- ematical insights often omitted from textbooks, his work may be very helpful to mathematics teachers and researchers. -

The Development of Calculus in the Kerala School

The Mathematics Enthusiast Volume 11 Number 3 Number 3 Article 5 12-2014 The development of Calculus in the Kerala School Phoebe Webb Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/tme Part of the Mathematics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Webb, Phoebe (2014) "The development of Calculus in the Kerala School," The Mathematics Enthusiast: Vol. 11 : No. 3 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/tme/vol11/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Mathematics Enthusiast by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TME, vol. 11, no. 3, p. 495 The Development of Calculus in the Kerala School Phoebe Webb1 University of Montana Abstract: The Kerala School of mathematics, founded by Madhava in Southern India, produced many great works in the area of trigonometry during the fifteenth through eighteenth centuries. This paper focuses on Madhava's derivation of the power series for sine and cosine, as well as a series similar to the well-known Taylor Series. The derivations use many calculus related concepts such as summation, rate of change, and interpolation, which suggests that Indian mathematicians had a solid understanding of the basics of calculus long before it was developed in Europe. Other evidence from Indian mathematics up to this point such as interest in infinite series and the use of a base ten decimal system also suggest that it was possible for calculus to have developed in India almost 300 years before its recognized birth in Europe. -

Collection of Series for Π

Collection of series for π Pascal Sebah and Xavier Gourdon numbers.computation.free.fr/Constants/constants.html March 31, 2004 Abstract Selection of some of the numerous series expansion involving the fa- mous constant π. 1 Introduction There are a great many numbers of series involving the constant π,weprovide a selection. The celebrated Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler (1707-1783) discovered many of those. 2 Around Leibniz-Gregory-Madhava series π 1 1 1 =1− + − + ··· (Leibniz-Gregory-Madhava) 4 3 5 7 π2 − k ( 1) 1 ··· 1 = k 1+ + + k (Knopp) 16 k≥0 +1 3 2 +1 π 3 1 1 1 = + − + −··· (Nilakantha) 4 4 2.3.4 4.5.6 6.7.8 π 1 1.2 1.2.3 =1+ + + + ··· (Euler) 2 3 3.5 3.5.7 π 1.2 1.2.3 1.2.3.4 = + + + ··· 2 1.3 1.3.5 1.3.5.7 k − π 3 1ζ k = k ( + 1) (Flajolet-Vardi) k≥1 4 π 1 = arctan k2 k (Knopp) 4 k≥1 + +1 π 1 = arctan F2k+1 4 k≥1 1 1 1 π π = k+1 tan k+1 (Euler) k≥1 2 2 √ π 2 1 1 1 1 1 =1+ − − + + −··· √4 3 5 7 9 11 π 3 1 1 1 1 1 =1− + − + − + ··· √6 5 7 11 13 17 π 3 1 1 1 1 1 =1− + − + − + ··· √9 2 4 5 7 8 π 3 (−1)k = k k (Sharp) 6 k≥0 3 (2 +1) The Fn are Fibonacci numbers. F0 =0,F1 =1,F2 =1,F3 =2,F4 =3,F5 =5, ..., Fn+1 = Fn + Fn−1. -

Infinite Series, Infinite Products, and Infinite Fractions

Part 3 Infinite series, infinite products, and infinite fractions CHAPTER 5 Advanced theory of infinite series Even as the finite encloses an infinite series And in the unlimited limits appear, So the soul of immensity dwells in minutia And in the narrowest limits no limit in here. What joy to discern the minute in infinity! The vast to perceive in the small, what divinity! Jacob Bernoulli (1654-1705) Ars Conjectandi. This chapter is about going in-depth into the theory and application of infinite series. One infinite series that will come up again and again in this chapter and the next chapter as well, is the Riemann zeta function 1 1 ζ(z) = ; nz n=1 X introduced in Section 4.6. Amongst many other things, in this chapter we'll see how to write some well-known constants in terms of the Riemann zeta function; e.g. we'll derive the following neat formula for our friend log 2 ( 5.5): x 1 1 log 2 = ζ(n); 2n n=2 X another formula for our friend the Euler-Mascheroni constant ( 5.9): x 1 ( 1)n γ = − ζ(n); n n=2 X and two more formulas involving our most delicious friend π (see 's 5.10 and 5.11): x 1 3n 1 π2 1 1 1 1 1 π = − ζ(n + 1) ; = ζ(2) = = 1 + + + + : 4n 6 n2 22 32 42 · · · n=2 n=1 X X In this chapter, we'll also derive Gregory-Leibniz-Madhava's formula ( 5.10) x π 1 1 1 1 1 = 1 + + + ; 4 − 3 5 − 7 9 − 11 − · · · and Machin's formula which started the \decimal place race" of computing π ( 5.10): x 1 1 1 ( 1)n 4 1 π = 4 arctan arctan = 4 − : 5 − 239 (2n + 1) 52n+1 − 2392n+1 n=0 X 229 230 5. -

MA 109: Calculus I

Department of Mathematics Indian Institute of Technology Bombay Powai, Mumbai{400 076, INDIA. MA 109: Calculus I November 2020 - January 2021 Instructors: Ravi Raghunathan 202-E, Department of Mathematics. Manoj Keshari 204-D, Department of Mathematics Website For course materials and updates please check http://www.math.iitb.ac.in/~ravir/ma109index. html These materials and updates will also be posted on \moodle", an online interface for the course. This should be already functional. Syllabus • The convergence of sequences and series. • A review of limits, continuity, differentiability. • The Mean Value Theorem, Taylor's theorem, power series, maxima and minima. • Riemann integrals, The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, improper integrals; applications to area and volume. • Partial derivatives, the gradient and directional derivatives, the chain rule, maxima and min- ima in several variables, Lagrange multipliers. Texts/References [Apo80] T.M. Apostol, Calculus, Volumes 1 and 2, 2nd ed., Wiley (2007). [Ste03] James Stewart, Calculus, 8th ed., Thomson (2011). [TF98] G.B. Thomas and R.L. Finney, Calculus and Analytic Geometry, 12th ed., Pearson (2015). Policy on Attendance Students are expected to attend all lectures and tutorial sessions. However, we do understand that many of you may face power cuts, unstable internet connections or other constraints. In that case, please make sure that you watch the recordings of the zoom lectures and tutorials. Please try to access the moodle site whenever your internet connections lets you do so. Evaluation Plan The evaluation plan has not been finalised since we are not sure of the quality of online access of our students. We are likely to have weekly short quizes of about 15 minutes each.