Kamala¯Kara Commentary on the Work, Called Tattvavivekodāharan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sanskrit Common for UG Courses 2009 Admission

KANNUR UNIVERSITY RESTRUCTURED CURRICULUM FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSES OFFERED BY THE BOARD OF STUDIES IN SANSKRIT (CD) 2009 ADMISSION ONWARDS (PREPARED AS PER THE REGULATION OF KANNUR UNIVERSITY & DIRECTIONS OF KERALA HIGHER EDUCATION COUNCIL) ``````````` 1 PREFACE The new revised syllabus is prepared as part of the involvement of restructuring Undergaduate Courses taken up by the Kerala State Higher Education Council in conformity with the National Educational Policy of University Grants Commission. In this connection the restructuring of Sanskrit syllabus bears an objective for preserving India’s age old cultural legacy and wisdom in the light of modern global views and trends. The revised syllabus of Sanskrit renders a flexible pattern of Choice Based Course Credit Semester System and will be in the nature of continuous assessment. The syllabus and curriculum are mainly student centred. The syllabus is designed in such a way that proper motivation is given in the pursuit of knowledge and culture. At the same time, ability to comprehensive skill, language proficiency, creative writing skill and literary taste constitute its aim. The Open Course is designed in such a way so as to utilize the valuable ethno-wisdom especially in the field of plant science and herbal wisdom as seen in Sanskrit language which will be an asset in public health. In another field of Open Course, the syllabus is designed to equip the students to face the challenges confronting in their life and enhance their social commitment. In short, the restructuring of the course is meant as the realization of the following aims: Character is formed, strength of mind is increased and by which the students can stand on one’s own legs and become an asset to the nation. -

1. Essent Vol. 1

ESSENT Society for Collaborative Research and Innovation, IIT Mandi Editor: Athar Aamir Khan Editorial Support: Hemant Jalota Tejas Lunawat Advisory Committee: Dr Venkata Krishnan, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi Dr Varun Dutt, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi Dr Manu V. Devadevan, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi Dr Suman, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi AcknowledgementAcknowledgements: Prof. Arghya Taraphdar, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur Dr Shail Shankar, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi Dr Rajeshwari Dutt, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi SCRI Support teamteam:::: Abhishek Kumar, Nagarjun Narayan, Avinash K. Chaudhary, Ankit Verma, Sourabh Singh, Chinmay Krishna, Chandan Satyarthi, Rajat Raj, Hrudaya Rn. Sahoo, Sarvesh K. Gupta, Gautam Vij, Devang Bacharwar, Sehaj Duggal, Gaurav Panwar, Sandesh K. Singh, Himanshu Ranjan, Swarna Latha, Kajal Meena, Shreya Tangri. ©SOCIETY FOR COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH AND INNOVATION (SCRI), IIT MANDI [email protected] Published in April 2013 Disclaimer: The views expressed in ESSENT belong to the authors and not to the Editorial board or the publishers. The publication of these views does not constitute endorsement by the magazine. The editorial board of ‘ESSENT’ does not represent or warrant that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete and in no case are they responsible for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from the use of such material. Readers are strongly advised to confirm the information contained herein with other dependable sources. ESSENT|Issue1|V ol1 ESSENT Society for Collaborative Research and Innovation, IIT Mandi CONTENTS Editorial 333 Innovation for a Better India Timothy A. Gonsalves, Director, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi 555 Research, Innovation and IIT Mandi 111111 Subrata Ray, School of Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi INTERVIEW with Nobel laureate, Professor Richard R. -

Bhaskara's Approximation to and Madhava's Series for Sine

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Transforming Instruction in Undergraduate Calculus Mathematics via Primary Historical Sources (TRIUMPHS) Winter 2020 Bhaskara's Approximation to and Madhava's Series for Sine Kenneth M. Monks [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/triumphs_calculus Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Monks, Kenneth M., "Bhaskara's Approximation to and Madhava's Series for Sine" (2020). Calculus. 15. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/triumphs_calculus/15 This Course Materials is brought to you for free and open access by the Transforming Instruction in Undergraduate Mathematics via Primary Historical Sources (TRIUMPHS) at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Calculus by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bh¯askara's Approximation to and M¯adhava's Series for Sine Kenneth M Monks∗ May 20, 2021 A chord is a very natural construction in geometry; it is the line segment obtained by connecting two points on a circle. Chords were studied extensively in ancient Greek geometry. For example, Euclid's Elements [Euclid, c. 300 BCE] contains plenty of theorems relating the circle's arc AB to the line segment AB (shown below).1 A B Indian mathematicians, motivated by astronomy, were the first to specifically calculate values of half-chords instead [Gupta, 1967, p. 121]. This work led very directly to the function which we call sine today. Task 1 Half-chords and sine. Suppose the circle above has radius 1. -

Aryabhatiya with English Commentary

ARYABHATIYA OF ARYABHATA Critically edited with Introduction, English Translation. Notes, Comments and Indexes By KRIPA SHANKAR SHUKLA Deptt. of Mathematics and Astronomy University of Lucknow in collaboration with K. V. SARMA Studies V. V. B. Institute of Sanskrit and Indological Panjab University INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY NEW DELHI 1 Published for THE NATIONAL COMMISSION FOR THE COMPILATION OF HISTORY OF SCIENCES IN INDIA by The Indian National Science Academy Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi— © Indian National Science Academy 1976 Rs. 21.50 (in India) $ 7.00 ; £ 2.75 (outside India) EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Chairman : F. C. Auluck Secretary : B. V. Subbarayappa Member : R. S. Sharma Editors : K. S. Shukla and K. V. Sarma Printed in India At the Vishveshvaranand Vedic Research Institute Press Sadhu Ashram, Hosbiarpur (Pb.) CONTENTS Page FOREWORD iii INTRODUCTION xvii 1. Aryabhata— The author xvii 2. His place xvii 1. Kusumapura xvii 2. Asmaka xix 3. His time xix 4. His pupils xxii 5. Aryabhata's works xxiii 6. The Aryabhatiya xxiii 1. Its contents xxiii 2. A collection of two compositions xxv 3. A work of the Brahma school xxvi 4. Its notable features xxvii 1. The alphabetical system of numeral notation xxvii 2. Circumference-diameter ratio, viz., tz xxviii table of sine-differences xxviii . 3. The 4. Formula for sin 0, when 6>rc/2 xxviii 5. Solution of indeterminate equations xxviii 6. Theory of the Earth's rotation xxix 7. The astronomical parameters xxix 8. Time and divisions of time xxix 9. Theory of planetary motion xxxi - 10. Innovations in planetary computation xxxiii 11. -

A Study on the Encoding Systems in Vedic Era and Modern Era 1K

International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics Volume 114 No. 7 2017, 425-433 ISSN: 1311-8080 (printed version); ISSN: 1314-3395 (on-line version) url: http://www.ijpam.eu Special Issue ijpam.eu A Study on the Encoding Systems in Vedic Era and Modern Era 1K. Lakshmi Priya and 2R. Parameswaran 1Department of Mathematics, School of Arts and Sciences, Amrita University, Kochi. [email protected] 2Department of Mathematics, School of Arts and Sciences, Amrita University, Kochi. [email protected] Abstract Encoding is the action of transferring a message in to codes. In this paper I present a study on the encoding systems in vedic era and modern era. The Sanskrit verses written in the vedic era are not just the praises of the Gods they are also numerical codes. In ancient India there were three means of recording numerals in Sanskrit words which are Katapayadi system, Bhutasamkhya system and Aryabhata numeration. These systems were used by many ancient mathematicians in India. In this paper the Katapayadi system used in vedic times is applied to modern ciphers– Vigenere Cipher and Affine Cipher. Key Words:Katapayadi system, vigenere cipher, affine cipher. 425 International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics Special Issue 1. Introduction Encoding is the process of transforming messages into an arrangement required for data transmission, storage and compression/decompression. In cryptography, encryption is the method of transforming information using an algorithm to make it illegible to anyone except those owning special information, usually called as a key. In vedic era, Sanskrit is the language used. It is supposed to be the ancient language, from which most of the modern dialects are developed. -

BOOK REVIEW a PASSAGE to INFINITY: Medieval Indian Mathematics from Kerala and Its Impact, by George Gheverghese Joseph, Sage Pu

HARDY-RAMANUJAN JOURNAL 36 (2013), 43-46 BOOK REVIEW A PASSAGE TO INFINITY: Medieval Indian Mathematics from Kerala and its impact, by George Gheverghese Joseph, Sage Publications India Private Limited, 2009, 220p. With bibliography and index. ISBN 978-81-321-0168-0. Reviewed by M. Ram Murty, Queen's University. It is well-known that the profound concept of zero as a mathematical notion orig- inates in India. However, it is not so well-known that infinity as a mathematical concept also has its birth in India and we may largely credit the Kerala school of mathematics for its discovery. The book under review chronicles the evolution of this epoch making idea of the Kerala school in the 14th century and afterwards. Here is a short summary of the contents. After a brief introduction, chapters 2 and 3 deal with the social and mathematical origins of the Kerala school. The main mathematical contributions are discussed in the subsequent chapters with chapter 6 being devoted to Madhava's work and chapter 7 dealing with the power series for the sine and cosine function as developed by the Kerala school. The final chapters speculate on how some of these ideas may have travelled to Europe (via Jesuit mis- sionaries) well before the work of Newton and Leibniz. It is argued that just as the number system travelled from India to Arabia and then to Europe, similarly many of these concepts may have travelled as methods for computational expediency rather than the abstract concepts on which these algorithms were founded. Large numbers make their first appearance in the ancient writings like the Rig Veda and the Upanishads. -

Global Positioning System (GPS)

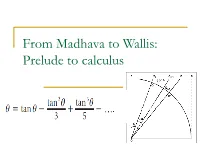

From Madhava to Wallis: Prelude to calculus Madhava and the Kerala school There is now considerable documentary evidence that many of the ideas needed for the development of calculus were already written down by what is now called the Kerala school of mathematics in south western India in the 14th century. Madhava (1340-1425 CE) was the foremost member of this school who developed the theory of the trigonometric functions and derived the familiar Taylor series expansions for them. His work was described in detail with proofs by Jyesthadeva who wrote the text called Yuktibhasha in the middle of the 16th century. Madhava series for the trigonometric functions Studying the sine and cosine function, Madhava derived the following well-known formulas: The last is the famous arctan series re-discovered by Gregory several centuries later. When θ=π/4, we get the famous Madhava-Gregory-Leibniz series for π. The series for arctan x Evaluation of the sum The migration of ideas and Father Mersenne According to George Joseph, author of the Crest of the Peacock, it is quite possible that many of the ideas of the Kerala school migrated through Jesuit missionaries to Europe. Most notable among the Jesuits was Father Marin Mersenne (1588-1648) who was a close friend of both Descartes and Fermat (in fact, many conjectures attributed to Fermat appear in his letters to Mersenne). Thus many of the ideas of calculus were “in the air”. The work of Cavalieri, Fermat, Mengoli and Gregory Mengoli and log 2 Mengoli discovered that 1-1/2 + 1/3 -1/4 + … converges to log 2. -

Mathematics Newsletter Volume 21. No4, March 2012

MATHEMATICS NEWSLETTER EDITORIAL BOARD S. Ponnusamy (Chief Editor) Department of Mathematics Indian Institute of Technology Madras Chennai - 600 036, Tamilnadu, India Phone : +91-44-2257 4615 (office) +91-44-2257 6615, 2257 0298 (home) [email protected] http://mat.iitm.ac.in/home/samy/public_html/index.html S. D. Adhikari G. K. Srinivasan Harish-Chandra Research Institute Department of Mathematics, (Former Mehta Research Institute ) Indian Institute of Technology Chhatnag Road, Jhusi Bombay Allahabad 211 019, India Powai, Mumbai 400076, India [email protected] [email protected] C. S. Aravinda B. Sury, TIFR Centre for Applicable Mathematics Stat-Math Unit, Sharadanagar, Indian Statistical Institute, Chikkabommasandra 8th Mile Mysore Road, Post Bag No. 6503 Bangalore 560059, India. Bangalore - 560 065 [email protected], [email protected] [email protected] M. Krishna G. P. Youvaraj The Institute of Mathematical Sciences Ramanujan Institute CIT Campus, Taramani for Advanced Study in Mathematics Chennai-600 113, India University of Madras, Chepauk, [email protected] Chennai-600 005, India [email protected] Stefan Banach (1892–1945) R. Anantharaman SUNY/College, Old Westbury, NY 11568 E-mail: rajan−[email protected] To the memory of Jong P. Lee Abstract. Stefan Banach ranks quite high among the founders and developers of Functional Analysis. We give a brief summary of his life, work and methods. Introduction (equivalent of middle/high school) there. Even as a student Stefan revealed his talent in mathematics. He passed the high Stefan Banach and his school in Poland were (among) the school in 1910 but not with high honors [M]. -

Chapter Two Astrological Works in Sanskrit

51 CHAPTER TWO ASTROLOGICAL WORKS IN SANSKRIT Astrology can be defined as the 'philosophy of discovery' which analyzing past impulses and future actions of both individuals and communities in the light of planetary configurations. Astrology explains life's reaction to planetary movements. In Sanskrit it is called hora sastra the science of time-'^rwRH ^5R5fai«fH5iref ^ ^Tm ^ ^ % ^i^J' 11 L.R. Chawdhary documented the use of astrology as "astrology is important to male or female as is the case of psychology, this branch of knowledge deals with the human soul deriving awareness of the mind from the careful examination of the facts of consciousness. Astrology complements everything in psychology because it explains the facts of planetary influences on the conscious and subconscious providing a guideline towards all aspects of life, harmony of mind, body and spirit. This is the real use of astrology^. Dr. ^.V.Raman implies that "astrology in India is a part of the whole of Indian culture and plays an integral part in guiding life for all at all stages of life" ^. Predictive astrology is a part of astronomy that exists by the influence of ganita and astronomical doctrines. Winternitz observes that an astrologer is required to possess all possible noble quantities and a comprehensive knowledge of astronomy, ' Quoted from Sabdakalpadruma, kanta-ll, p.550 ^ L.R.Chawdhari, Secrets of astrology. Sterling Paper backs, New Delhi,1998, p.3 ^Raman.B.V, Planetary influence of Human affairs, U.B.S. Publishers, New Delhi, 1996,p.147 52 mathematics and astrology^ Astrology or predictive astrology is said to be coconnected with 'astronomy'. -

An Anecdote on Mādhava School of Mathematics

Insight: An International Journal for Arts and Humanities Peer Reviewed and Refereed Vol: 1; Issue: 3 ISSN: 2582-8002 An Anecdote on Mādhava School of Mathematics Athira K Babu Research Scholar, Department of Sanskrit Sahitya, Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, Kalady, Abstract The Sanskrit term ‘Gaṇitaśāstra’, meaning literally the “science of calculation” is used for mathematics. The mathematical tradition of ancient India is an ocean of knowledge that is dealing with many topics such as the Vedic, Jain and Buddhist traditions, the mathematical astronomy, The Bhakshali manuscripts, The Kerala School of mathematics and the like. Thus India has made a valuable contribution to the world of mathematics. The origin and development of Indian mathematics are connected with Jyotiśāstra1. This paper tries to deconstructing the concept of mathematical tradition of Kerala with respect to Niḷā valley civilization especially under the background of medieval Kerala and also tries to look into the Mādhava School of mathematics through the life and works of great mathematician Mādhava of Saṅgamagrāma and his pupils who lived in and around the river Niḷā. Keywords: Niḷā, Literature review, Mathematical Tradition of medieval Kerala, Mādhava of Saṅgamagrāma, Great lineage of Mādhava. Introduction Niḷā, the Nile of Kerala is famous for the great ‘Māmāṅkam’ festival. The word ‘Niḷā’point out a culture more than just a river. It has a great role in the formation of the cultural life of south Malabar part of Kerala. It could be seen that the word ‘Peraar’ indicating the same river in ancient scripts and documents. The Niḷā is the life line of many places such as Chittur, Ottappalam, Shornur, Cheruthuruthy, Pattambi, Thrithala, Thiruvegappura, Kudallur, Pallippuram, Kumbidi, 1 The Sanskrit word used for Astronomy is Jyotiśāstra. -

Approximation of Alternating Series Using Correction Function and Error Function

International Journal of Scientific and Innovative Mathematical Research (IJSIMR) Volume 4, Issue 8, August 2016, PP 24-26 ISSN 2347-307X (Print) & ISSN 2347-3142 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2347-3142.0408004 www.arcjournals.org Approximation of Alternating Series using Correction Function and Error Function Kumari Sreeja S Nair Dr.V.Madhukar Mallayya Assistant Professor of Mathematics Former Professor and Head Govt.Arts College, Thiruvananthapuram, Department of Mathematics Kerala, India Mar Ivanios College Thiruvananthapuram, India Abstract: In this paper we give a rational approximation of an alternating series using remainder term of the series. For that we shall introduce a correction function to the series. The correction function plays a vital role in series approximation. Using correction function we shall deduce an error function to the series. Keywords: Correction function, error function, remainder term, alternating series, Madhava series, rational approximation. 1. INTRODUCTION In 14푡ℎ century, the Indian mathematician Madhava gave an approximation of the pi series using remainder term of the series. Madhava series is, 4푑 4푑 4푑 ..................... 푛−1 4푑 푛 4푑(2푛)/2 C = − + − +(−1) + (−1) , where C is the circumference of a 1 3 5 2푛−1 2푛 2+1 (2푛)/2 circle of diameter d. Here the remainder term is (-1)n 4d G where G = is the correction n n 2푛 2+1 function. The introduction of the correction term gives a better approximation of the series. 2. METHOD 푛−1 ∞ (−1) APPROXIMATION OF THE ALTERNATING SERIES 푛=1 푛 푛+1 (푛+2) (−1)푛−1 The alternating series ∞ satisfies the conditions of alternating series test and so it is 푛=1 푛 푛+1 (푛+2) convergent. -

JETIR Research Journal

© 2020 JETIR November 2020, Volume 7, Issue 11 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Exploring the Algebraic and Geometric Nature of 흅. 1*Archisman Roy, 2Tushar Banerjee 1Author (Student), AOSHS, Higher Secondary School of Science; 2Research Scholar, SSSUTMS 1Department of Science, 2Department of Zoology 1Asansol, India. * denotes correspondence Abstract: This bodacious study has been endeavored to probe different natures of π. Π comes from the Greek script of the word ‘periphery’ which means circumference. In connection to that π has a birthright for claiming geometry as its origin. Metaphorically, it is a real and definite number which is algebraically inexpressible. Our piece of research is thus willing to persuade that every geometric relation can be expressed with some equations of algebra and each algebraic expansion has its geometric interpretation. In addition to that, the article produces numerously validated as well as cited works of famous mathematicians to cajole about the article's plausibility. It approaches a good deal of mathematical history for congenially maintaining its engagement with the content. Sufficient statistical data have been produced to sway every bit of the mathematical perspective. The piece of writing consists of suitable graphs and images adhering to its requirement. Furthermore, it expresses enthusiastically about its new substantial contribution regarding the cognizance of π. Finally, the article suffers a lenient way of producing π subsequently through three stages of visualizing a mathematical paradox viz geometric background, augmentation of algebra, and the real connection between them both. Index Terms - Irrational, constant, transcendental, infinite-fraction, exact. I. INTRODUCTION The world of algebraical mathematics especially the number theorems are gigantically fascinated by a few irrational numbers such as Euler's constant 'e' and the 'π'.