Explaining Relationships in Scientific and Technical Texts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scientists on Currencies

“For making the world a wealthier place” TOP 10 ___________________________________________________________________________________ SCIENTISTS ON BANKNOTES 1. Isaac Newton 2. Charles Darwin 3. Michael Faraday 4. Copernicus 5. Galileo 6. Marie Curie 7. Leonardo da Vinci 8. Albert Einstein 9. Hideyo Noguchi 10. Nikola Tesla Will Philip Emeagwali be on the Nigerian Money? “Put Philip Emeagwali on Nigeria’s Currency,” Central Bank of Nigeria official pleads. See Details Below Physicist Albert Einstein is honored on Israeli five pound currency. Galileo Gallilei on the Italian 2000 Lire. Isaac Newton honored on the British pound. Bacteriologist Hideyo Noguchi honored on the Japanese banknote. The image of Carl Friedrich Gauss on Germany's 10- mark banknote inspired young Germans to become mathematicians. Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519), the Italian polymath, is honored on their banknote. Maria Sklodowska–Curie is honoured on the Polish banknote. Carl Linnaeus is honored on the Swedish banknote (100 Swedish Krona) Nikola Tesla is honored on Serbia’s banknote. Note actual equation on banknote (Serbia’s 100-dinar note) Honorable Mentions Developing Story Banker Wanted Emeagwali on Nigerian Currency In early 2000s, the Central Bank of Nigeria announced that new banknotes will be commissioned. An economist of the Central Bank of Nigeria commented: “In Europe, heroes of science are portrayed on banknotes. In Africa, former heads of state are portrayed on banknotes. Why is that so?” His logic was that the Central Bank of Nigeria should end its era of putting only Nigerian political leaders on the money. In Africa, only politicians were permitted by politicians to be on the money. Perhaps, you’ve heard of the one-of-a-kind debate to put Philip Emeagwali on the Nigerian money. -

Alessandro Volta and the Discovery of the Battery

1 Primary Source 12.2 VOLTA AND THE DISCOVERY OF THE BATTERY1 Alessandro Volta (1745–1827) was born in the Duchy of Milan in a town called Como. He was raised as a Catholic and remained so throughout his life. Volta became a professor of physics in Como, and soon took a significant interest in electricity. First, he began to work with the chemistry of gases, during which he discovered methane gas. He then studied electrical capacitance, as well as derived new ways of studying both electrical potential and charge. Most famously, Volta discovered what he termed a Voltaic pile, which was the first electrical battery that could continuously provide electrical current to a circuit. Needless to say, Volta’s discovery had a major impact in science and technology. In light of his contribution to the study of electrical capacitance and discovery of the battery, the electrical potential difference, voltage, and the unit of electric potential, the volt, were named in honor of him. The following passage is excerpted from an essay, written in French, “On the Electricity Excited by the Mere Contact of Conducting Substances of Different Kinds,” which Volta sent in 1800 to the President of the Royal Society in London, Joseph Banks, in hope of its publication. The essay, described how to construct a battery, a source of steady electrical current, which paved the way toward the “electric age.” At this time, Volta was working as a professor at the University of Pavia. For the excerpt online, click here. The chief of these results, and which comprehends nearly all the others, is the construction of an apparatus which resembles in its effects viz. -

The Concept of Field in the History of Electromagnetism

The concept of field in the history of electromagnetism Giovanni Miano Department of Electrical Engineering University of Naples Federico II ET2011-XXVII Riunione Annuale dei Ricercatori di Elettrotecnica Bologna 16-17 giugno 2011 Celebration of the 150th Birthday of Maxwell’s Equations 150 years ago (on March 1861) a young Maxwell (30 years old) published the first part of the paper On physical lines of force in which he wrote down the equations that, by bringing together the physics of electricity and magnetism, laid the foundations for electromagnetism and modern physics. Statue of Maxwell with its dog Toby. Plaque on E-side of the statue. Edinburgh, George Street. Talk Outline ! A brief survey of the birth of the electromagnetism: a long and intriguing story ! A rapid comparison of Weber’s electrodynamics and Maxwell’s theory: “direct action at distance” and “field theory” General References E. T. Wittaker, Theories of Aether and Electricity, Longam, Green and Co., London, 1910. O. Darrigol, Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einste in, Oxford University Press, 2000. O. M. Bucci, The Genesis of Maxwell’s Equations, in “History of Wireless”, T. K. Sarkar et al. Eds., Wiley-Interscience, 2006. Magnetism and Electricity In 1600 Gilbert published the “De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure” (On the Magnet and Magnetic Bodies, and on That Great Magnet the Earth). ! The Earth is magnetic ()*+(,-.*, Magnesia ad Sipylum) and this is why a compass points north. ! In a quite large class of bodies (glass, sulphur, …) the friction induces the same effect observed in the amber (!"#$%&'(, Elektron). Gilbert gave to it the name “electricus”. -

08. Ampère and Faraday Darrigol (2000), Chap 1

08. Ampère and Faraday Darrigol (2000), Chap 1. A. Pre-1820. (1) Electrostatics (frictional electricity) • 1780s. Coulomb's description: ! Two electric fluids: positive and negative. ! Inverse square law: It follows therefore from these three tests, that the repulsive force that the two balls -- [which were] electrified with the same kind of electricity -- exert on each other, Charles-Augustin de Coulomb follows the inverse proportion of (1736-1806) the square of the distance."" (2) Magnetism: Coulomb's description: • Two fluids ("astral" and "boreal") obeying inverse square law. • No magnetic monopoles: fluids are imprisoned in molecules of magnetic bodies. (3) Galvanism • 1770s. Galvani's frog legs. "Animal electricity": phenomenon belongs to biology. • 1800. Volta's ("volatic") pile. Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) • Pile consists of alternating copper and • Charged rod connected zinc plates separated by to inner foil. brine-soaked cloth. • Outer foil grounded. • A "battery" of Leyden • Inner and outer jars that can surfaces store equal spontaeously recharge but opposite charges. themselves. 1745 Leyden jar. • Volta: Pile is an electric phenomenon and belongs to physics. • But: Nicholson and Carlisle use voltaic current to decompose Alessandro Volta water into hydrogen and oxygen. Pile belongs to chemistry! (1745-1827) • Are electricity and magnetism different phenomena? ! Electricity involves violent actions and effects: sparks, thunder, etc. ! Magnetism is more quiet... Hans Christian • 1820. Oersted's Experimenta circa effectum conflictus elecrici in Oersted (1777-1851) acum magneticam ("Experiments on the effect of an electric conflict on the magnetic needle"). ! Galvanic current = an "electric conflict" between decompositions and recompositions of positive and negative electricities. ! Experiments with a galvanic source, connecting wire, and rotating magnetic needle: Needle moves in presence of pile! "Otherwise one could not understand how Oersted's Claims the same portion of the wire drives the • Electric conflict acts on magnetic poles. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW of BASIC ELECTRICAL CONCEPTS for FIELD MEASUREMENT TECHNICIANS Part 1 – Basic Electrical Concepts

A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF BASIC ELECTRICAL CONCEPTS FOR FIELD MEASUREMENT TECHNICIANS Part 1 – Basic Electrical Concepts Gerry Pickens Atmos Energy 810 Crescent Centre Drive Franklin, TN 37067 The efficient operation and maintenance of electrical and metal. Later, he was able to cause muscular contraction electronic systems utilized in the natural gas industry is by touching the nerve with different metal probes without substantially determined by the technician’s skill in electrical charge. He concluded that the animal tissue applying the basic concepts of electrical circuitry. This contained an innate vital force, which he termed “animal paper will discuss the basic electrical laws, electrical electricity”. In fact, it was Volta’s disagreement with terms and control signals as they apply to natural gas Galvani’s theory of animal electricity that led Volta, in measurement systems. 1800, to build the voltaic pile to prove that electricity did not come from animal tissue but was generated by contact There are four basic electrical laws that will be discussed. of different metals in a moist environment. This process They are: is now known as a galvanic reaction. Ohm’s Law Recently there is a growing dispute over the invention of Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law the battery. It has been suggested that the Bagdad Kirchhoff’s Current Law Battery discovered in 1938 near Bagdad was the first Watts Law battery. The Bagdad battery may have been used by Persians over 2000 years ago for electroplating. To better understand these laws a clear knowledge of the electrical terms referred to by the laws is necessary. Voltage can be referred to as the amount of electrical These terms are: pressure in a circuit. -

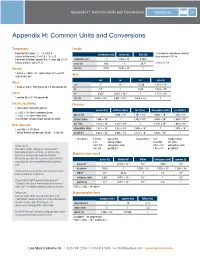

Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Appendices 215

Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Appendices 215 Appendix H: Common Units and Conversions Temperature Length Fahrenheit to Celsius: °C = (°F-32)/1.8 1 micrometer (sometimes referred centimeter (cm) meter (m) inch (in) Celsius to Fahrenheit: °F = (1.8 × °C) + 32 to as micron) = 10-6 m Fahrenheit to Kelvin: convert °F to °C, then add 273.15 centimeter (cm) 1 1.000 × 10–2 0.3937 -3 Celsius to Kelvin: add 273.15 meter (m) 100 1 39.37 1 mil = 10 in Volume inch (in) 2.540 2.540 × 10–2 1 –3 3 1 liter (l) = 1.000 × 10 cubic meters (m ) = 61.02 Area cubic inches (in3) cm2 m2 in2 circ mil Mass cm2 1 10–4 0.1550 1.974 × 105 1 kilogram (kg) = 1000 grams (g) = 2.205 pounds (lb) m2 104 1 1550 1.974 × 109 Force in2 6.452 6.452 × 10–4 1 1.273 × 106 1 newton (N) = 0.2248 pounds (lb) circ mil 5.067 × 10–6 5.067 × 10–10 7.854 × 10–7 1 Electric resistivity Pressure 1 micro-ohm-centimeter (µΩ·cm) pascal (Pa) millibar (mbar) torr (Torr) atmosphere (atm) psi (lbf/in2) = 1.000 × 10–6 ohm-centimeter (Ω·cm) –2 –3 –6 –4 = 1.000 × 10–8 ohm-meter (Ω·m) pascal (Pa) 1 1.000 × 10 7.501 × 10 9.868 × 10 1.450 × 10 = 6.015 ohm-circular mil per foot (Ω·circ mil/ft) millibar (mbar) 1.000 × 102 1 7.502 × 10–1 9.868 × 10–4 1.450 × 10–2 2 0 –3 –2 Heat flow rate torr (Torr) 1.333 × 10 1.333 × 10 1 1.316 × 10 1.934 × 10 5 3 2 1 1 watt (W) = 3.413 Btu/h atmosphere (atm) 1.013 × 10 1.013 × 10 7.600 × 10 1 1.470 × 10 1 British thermal unit per hour (Btu/h) = 0.2930 W psi (lbf/in2) 6.897 × 103 6.895 × 101 5.172 × 101 6.850 × 10–2 1 1 torr (Torr) = 133.332 pascal (Pa) 1 pascal (Pa) = 0.01 millibar (mbar) 1.33 millibar (mbar) 0.007501 torr (Torr) –6 A Note on SI 0.001316 atmosphere (atm) 9.87 × 10 atmosphere (atm) 2 –4 2 The values in this catalog are expressed in 0.01934 psi (lbf/in ) 1.45 × 10 psi (lbf/in ) International System of Units, or SI (from the Magnetic induction B French Le Système International d’Unités). -

Automatic Irrigation : Sensors and System

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1970 Automatic Irrigation : Sensors and System Herman G. Hamre Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Recommended Citation Hamre, Herman G., "Automatic Irrigation : Sensors and System" (1970). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3780. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/3780 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUTOMATIC IRRIGATION: SENSORS AND SYSTEM BY HERMAN G. HAMRE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science, Major in Electrical Engineering, South Dakota State University 1970 SOUTH DAKOTA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY AUTOMATIC IRRIGATION: SENSORS AND SYSTEM This thesis is approved as a creditable and independent investi gation by a candidate for the degree, Master of Science, and is accept able as meeting the thesis requirements for this degree, but without implying that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. �--- -"""'" _ _ -���--- - _ _ _ _____ -A>� - 7 7 T b � s/./ifjvisor ate Head, Electrical -r-oate Engineering Department ACKNOWLE GEMENTS The author wishes to express his sincere appreciation to Dr. A. J. Kurtenbach for his patient guidance and helpful suggestions, and to the Water Resources Institute for their support of this research. -

Electricity and Magnetism

Lecture 10 Fundamentals of Physics Phys 120, Fall 2015 Electricity and Magnetism A. J. Wagner North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND 58102 Fargo, September 24, 2015 Overview • Unexplained phenomena • Charges and electric forces revealed • Currents and circuits • Electricity and Magnetism are related! 1 Newton’s dream I wish we could derive the rest of the phenomena of Nature by the same kind of reasoning from mechanical principles, for I am induced by many reasons to suspect that they may all depend upon certain forces by which the particles of bodies, by some cause hitherto unknown, are either mutually impelled towards one another, and cohere in regular figures, or are repelled and recede from one another. from the preface of Newton’s Principia 2 What were those mysterious phenomena? 900 BC: Magnus, a Greek shepherd, walks across a field of black stones which pull the iron nails out of his sandals and the iron tip from his shepherd’s staff (authenticity not guaranteed). This region becomes known as Magnesia. 600 BC: Thales of Miletos(Greece) discovered that by rubbing an ’elektron’ (a hard, fossilized resin that today is known as amber) against a fur cloth, it would attract particles of straw and feathers. This strange effect remained a mystery for over 2000 years. 1269 AD: Petrus Peregrinus of Picardy, Italy, discovers that natural spherical magnets (lodestones) align needles with lines of longitude pointing between two pole positions on the stone. 3 ca. 1600: Dr.William Gilbert (court physician to Queen Elizabeth) discovers that the earth is a giant magnet just like one of the stones of Peregrinus, explaining how compasses work. -

Physics 115 Lightning Gauss's Law Electrical Potential Energy Electric

Physics 115 General Physics II Session 18 Lightning Gauss’s Law Electrical potential energy Electric potential V • R. J. Wilkes • Email: [email protected] • Home page: http://courses.washington.edu/phy115a/ 5/1/14 1 Lecture Schedule (up to exam 2) Today 5/1/14 Physics 115 2 Example: Electron Moving in a Perpendicular Electric Field ...similar to prob. 19-101 in textbook 6 • Electron has v0 = 1.00x10 m/s i • Enters uniform electric field E = 2000 N/C (down) (a) Compare the electric and gravitational forces on the electron. (b) By how much is the electron deflected after travelling 1.0 cm in the x direction? y x F eE e = 1 2 Δy = ayt , ay = Fnet / m = (eE ↑+mg ↓) / m ≈ eE / m Fg mg 2 −19 ! $2 (1.60×10 C)(2000 N/C) 1 ! eE $ 2 Δx eE Δx = −31 Δy = # &t , v >> v → t ≈ → Δy = # & (9.11×10 kg)(9.8 N/kg) x y 2" m % vx 2m" vx % 13 = 3.6×10 2 (1.60×10−19 C)(2000 N/C)! (0.01 m) $ = −31 # 6 & (Math typos corrected) 2(9.11×10 kg) "(1.0×10 m/s)% 5/1/14 Physics 115 = 0.018 m =1.8 cm (upward) 3 Big Static Charges: About Lightning • Lightning = huge electric discharge • Clouds get charged through friction – Clouds rub against mountains – Raindrops/ice particles carry charge • Discharge may carry 100,000 amperes – What’s an ampere ? Definition soon… • 1 kilometer long arc means 3 billion volts! – What’s a volt ? Definition soon… – High voltage breaks down air’s resistance – What’s resistance? Definition soon.. -

Physics, Chapter 30: Magnetic Fields of Currents

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 30: Magnetic Fields of Currents Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 30: Magnetic Fields of Currents" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 151. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/151 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 30 Magnetic Fields of Currents 30-1 Magnetic Field around an Electric Current The first evidence for the existence of a magnetic field around an electric current was observed in 1820 by Hans Christian Oersted (1777-1851). He found that a wire carrying current caused a freely pivoted compass needle B D N rDirection I of current D II. • ~ I I In wire ' \ N I I c , I s c (a) (b) Fig. 30-1 Oersted's experiment. Compass needle is deflected toward the west when the wire CD carrying current is placed above it and the direction of the current is toward the north, from C to D. in its vicinity to be deflected. If the current in a long straight wire is directed from C to D, as shown in Figure 30-1, a compass needle below it, whose initial orientation is shown in dotted lines, will have its north pole deflected to the left and its south pole deflected to the right. -

André-Marie Ampère Alessandro Volta Electricité James Prescott

des Sciences Alessandro Volta Le compte Alessandro Guiseppe Antonio Anastasio Volta, né à Côme le 18 février 1745 et mort dans cette même ville le 5 mars 1827. Il est connu pour ses travaux sur l'électricité et pour l'invention de la première pile électrique. Son nom est a l'origine de l'unité de tension électrique : Volt (symbole V). Il invente en 1800 la première pile nommé la pile voltaïque. Il réalise un montage composée de rondelles de cuivres et de zinc superposées et séparées les uns des autres par des rondelles de carton ou du tissu imbibé de saumure, pour servir de conducteur. La pile est reliée de haut en bas par un fil conducteur. André-Marie Ampère André-Marie Ampère est un mathématicien, physicien, chimiste, philosophe français né à Lyon en 1775 et mort à Marseille en 1836. Il apprend les sciences grâce à la bibliothèque de son père qui est philosophe. Il est connu pour ces travaux sur l‛‛électromagnétisme en fondant les base de l‛électronique de la matière. Il inventa le solénoïde, le télégraphe électrique et l‛‛électro-aimant. Il donna son nom à l‛intensité du courant électrique : Ampère (symbole A). Electricité Des phénomènes naturels, comme la foudre, étaient déjà observés dès l'Antiquité, mais pendant très longtemps l'électricité a terrifié les hommes qui trouvaient en elles une manifestation de la colère divine ou d'un pouvoir surnaturel. L'électricité a commencé à être étudiée par les scientifiques à la fin du 16e siècle pour en comprendre les mécanisme et établir des lois.