Alternative Market Values? Interventions Into Auctions in Aotearoa/New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hāngaitanga | Relevance

Tauhere | Connections, Issue 1, May 2016. 1 Hāngaitanga | Relevance Issue 1, May 2016. Tauhere | Connections, Issue 1, May 2016. 2 Committee members: Rebecca Keenan, editor Tamara Patten, editor Shelley Arlidge, sub-editor Jessica Mio, sub-editor Serena Siegenthaler, designer Milly Mitchell-Anyon, web developer MA Board liaisons: Talei Langley Daniel Stirland With much gratitude for the support and advice of: Elspeth Hocking Migoto Eria Ashley Remer Emerging Museum Professionals Group c/o Museums Aotearoa, 104 The Terrace, Wellington, New Zealand. www.tauhere.org | [email protected] ISSN 2463-5693 Tauhere | Connections, Issue 1, May 2016. 3 Content Page 3 Editorial Page 5 The Dowager Empress Cixi’s comb: A provenance treasure hunt Jane Groufsky Page 10 A Māori perspective on the localised relevance of museums and their community relationships Teina Ruri Page 17 Cultural institutions and the social compact Courtney Johnston Page 24 Potential Chloe Searle Page 28 Exclusion in the art gallery Elspeth Hocking Page 32 Curating outside your comfort zone Aimee Burbery Page 38 The Canterbury Cultural Collections Recovery Centre: Reflections of an intern Moya Sherriff Tauhere | Connections, Issue 1: Hāngaitanga | Relevance Editorial Nau mai, haere mai. Each piece approaches the relevance Welcome to the inaugural issue of of museums in a unique way, with Tauhere | Connections. discussions around the following: collection care in the wake of the Tauhere | Connections was Canterbury earthquakes, major conceived by the Emerging Museum developments in a regional museum Professionals group as a way to context, researching an object’s address a gap in New Zealand’s backstory, the challenges of curation museum publications offering – a in an unfamiliar subject area, an professional journal for the museum exploration of tikanga Māori in a sector that is not tied to the work of a museum context, comparing and single institution. -

The Whare-Oohia: Traditional Maori Education for a Contemporary World

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. TE WHARE-OOHIA: TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION FOR A CONTEMPORARY WORLD A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Education at Massey University, Palmerston North, Aotearoa New Zealand Na Taiarahia Melbourne 2009 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS He Mihi CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 The Research Question…………………………………….. 5 1.2 The Thesis Structure……………………………………….. 6 CHAPTER 2: HISTORY OF TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION 9 2.1 The Origins of Traditional Maaori Education…………….. 9 2.2 The Whare as an Educational Institute……………………. 10 2.3 Education as a Purposeful Engagement…………………… 13 2.4 Whakapapa (Genealogy) in Education…………………….. 14 CHAPTER 3: LITERATURE REVIEW 16 3.1 Western Authors: Percy Smith;...……………………………………………… 16 Elsdon Best;..……………………………………………… 22 Bronwyn Elsmore; ……………………………………….. 24 3.2 Maaori Authors: Pei Te Hurinui Jones;..…………………………………….. 25 Samuel Robinson…………………………………………... 30 CHAPTER 4: RESEARCHING TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION 33 4.1 Cultural Safety…………………………………………….. 33 4.2 Maaori Research Frameworks…………………………….. 35 4.3 The Research Process……………………………………… 38 CHAPTER 5: KURA - AN ANCIENT SCHOOL OF MAAORI EDUCATION 42 5.1 The Education of Te Kura-i-awaawa;……………………… 43 Whatumanawa - Of Enlightenment..……………………… 46 5.2 Rangi, Papa and their Children, the Atua:…………………. 48 Nga Atua Taane - The Male Atua…………………………. 49 Nga Atua Waahine - The Female Atua…………………….. 52 5.3 Pedagogy of Te Kura-i-awaawa…………………………… 53 CHAPTER 6: TE WHARE-WAANANGA - OF PHILOSOPHICAL EDUCATION 55 6.1 Whare-maire of Tuhoe, and Tupapakurau: Tupapakurau;...……………………………………………. -

MAI a WAIWIRI KI WAITOHU: How Mātauranga Māori Enhances Iwi and Hapū Well Being and Ecological Integrity

Manaaki Taha Moana: Enhancing Coastal Ecosystems for Iwi and Hapū Report No. 18 November 2015 MAI A WAIWIRI KI WAITOHU: How Mātauranga Māori Enhances Iwi and Hapū Well Being and Ecological Integrity MAI A WAIWIRI KI WAITOHU: How Mātauranga Māori Enhances Iwi and Hapū Well Being and Ecological Integrity Dr Huhana Smith [With support from Horowhenua MTM team- Moira Poutama and Aroha Spinks.] ISBN 978-0-9876639-7-9 ISSN 2230-3332 (Print) ISSN 2230-3340 (Online) Published by the Manaaki Taha Moana (MTM) Research Team Funded by the Ministry for Science and Innovation Contract MAUX0907 Main Contract Holder: Massey University www.mtm.ac.nz Approved for release Reviewed by: by: Cultural Advisor MTM Science Leader Mr Lindsay Poutama Professor Murray Patterson Issue Date: November 2015 RECOMMENDED CITATION: Smith, H., 2015, MAI A WAIWIRI KI WAITOHU: How Mātauranga Māori Enhances Iwi and Hapū Well Being and Ecological Integrity, Manaaki Taha Moana Research Project, Massey University: Palmerston North/Taiao Raukawa Environmental Resource Unit: Ōtaki. 43 pages © Copyright: Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, this publication must not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written permission of the Copyright Holder, who, unless other authorship is cited in the text or acknowledgements, is the commissioner of the report. MIHIMIHI1 Tuia i runga, tuia i raro, tuia i waho, tuia i roto, tuia te here tangata, ka rongo te pō, ka rongo te ao. Ka tuku te ia o whakaaro kia rere makuru roimata atu ki te kāhui ngū kua hoki atu ki te waro huanga roa o te wairua, rātou kei tua o te ārai, takoto, okioki, e moe. -

The Pacifist Traditions of Parihaka

Reclaiming the Role of Rongo: The Pacifist Traditions of Parihaka. Introduction: This paper seeks to introduce a form of radical politics centred on the role of Rongo, the Māori god of peace. As part of the focus on Rongo, this paper will discuss the pacifist traditions of Parihaka, the Day of Reconciliation and what the future trajectory for Parihaka may hold. The theoretical analysis will encompass a discourse analysis of the traditional waiata or Maori songs, as well as highlight the living history component of Parihaka by following an autoethnographic approach. The central question behind this paper asks whether the pacifism of the past influenced by the scriptures is less influential and needs to be replaced by an understanding of Rongo – a revolutionary and radical form of nonviolent politics. History and context of Parihaka: Parihaka was established in 1867 in Taranaki, the west coast of the north island of New Zealand. It wasn’t the first Maori settlement of peace in Taranaki, it followed on from other attempts to establish a peaceful community at Warea, Ngākumikumi, Te Puru, Kēkēua and Waikoukou. The leaders of the movement Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kakahi were well versed in the bible and decided to provide refuge to the landless Maori of Taranaki who had suffered the land confiscations in the 1860’s. Although the land was confiscated, it wasn’t enforced north of the Waingōngoro river from 1865 to 1878. (Riseborough, 1989, p. 31) The influence of Parihaka grew overtime, and it became difficult for government officials to bypass Te Whiti and Tohu, who were patient on waiting for their reserves that were promised to them. -

He Atua, He Tipua, He Tākata Rānei: an Analysis of Early South Island Māori Oral Traditions

HE ATUA, HE TIPUA, HE TAKATA RĀNEI: THE DYNAMICS OF CHANGE IN SOUTH ISLAND MĀORI ORAL TRADITIONS A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Māori in the University of Canterbury by Eruera Ropata Prendergast-Tarena University of Canterbury 2008 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgments .............................................................................................5 Abstract..............................................................................................................7 Glossary .............................................................................................................8 Technical Notes .................................................................................................9 Part One: The Whakapapa of Literature..........................................................10 Chapter 1......................................................................................................... 11 Introduction......................................................................................................12 Waitaha.........................................................................................................13 Myth and History .........................................................................................14 Authentic Oral Tradition..............................................................................15 Models of Oral Tradition .............................................................................18 The Dynamics -

Ngāti Kahu's Treaty Claims

Tihei Oreore Monograph Series - PUBLIC SEMINARS Tihei Oreore Monograph Series PUBLIC SEMINARS Dec. 2005 - Volume 1, Issue 1 Dec. 2005 - Volume ISBN 1177-1860 ISBN 0-9582610-2-4 December 2005 - Volume 1, Issue 1 This monograph has been published by Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga The National Institute of Research Excellence for Māori Development and Advancement Contact details: Waipapa Marae Complex 16 Wynyard Street Private Bag 92019 The University of Auckland New Zealand www.maramatanga.ac.nz Explanation of Title: The title ‘Tihei Oreore’ heralds the awakening of indigenous peoples. This monograph provides a forum for the publication of some of their research and writings. ISSN 1177-1860 ISBN 0-9582610-2-4 © Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga holds copyright for this monograph while individual authors hold copyright for their own articles. This publication cannot be reproduced and sold for profit by others. NGĀ PAE O TE MĀRAMATANGA PUBLIC SEMINAR SERIES Series Editor J.S. Te Rito Editors: Bruce Duffin, Phoebe Fletcher and Jan Sinclair Background on Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga is one of seven Centres of Research Excellence that were funded by the New Zealand Government in 2002. It was established as The National Institute of Research Excellence for Māori Development and Advancement and is hosted by the University of Auckland. Its participating entities are spread throughout New Zealand. The Institute offers three distinct but intersecting programmes: Research, Capability Building and Knowledge Exchange. Whakataukī (Proverb) Ko te pae tawhiti arumia kia tata Seek to bring the distant horizon closer Ko te pae tata whakamaua But grasp the closer horizon Kia puta i te wheiao ki te aomārama So you may emerge from darkness into enlightenment The Māori name for the Institute means “horizons of insight”. -

He Mangōpare Amohia

He Mangōpare Amohia STRATEGIES FOR MĀORI ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT He Mangōpare Amohia STRATEGIES FOR MĀORI ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AUTHORS Graham Hingangaroa Smith Rāwiri Tinirau Annemarie Gillies Virginia Warriner RESEARCH PARTNERS Te Rūnanga o Ngāti Awa Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga EDITORIAL SERVICES Moana Dawson – Simple Media PHOTOGRAPHY AND DESIGN Simone Magner – Simone Magner Photography ISBN NUMBER 978-0-473-32355-4 COPYRIGHT © Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi 2015 A report published by Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi Private Bag 1006 Whakatāne 3158 Aotearoa / New Zealand [email protected] 4 | HE MANGŌPARE AMOHIA – STRATEGIES FOR MĀORI ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT He Mangōpare Amohia STRATEGIES FOR MĀORI ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT NGĀ PAE O TE MĀRAMATANGA HE MANGŌPARE AMOHIA – STRATEGIES FOR MĀORI ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT | 5 HE KUPU WHAKATAKI FOREWORD Rukuhia te mātauranga ki tōna hōhonutanga me tōna whānuitanga. Whakakiia ngā kete a ngā uri o Awanuiārangi me te iwi Māori whānui ki ngā taonga tuku iho, ki te hōhonutanga me te whānuitanga o te mātauranga, kia tū tangata ai rātou i ngā rā e tū mai nei. E ngā mana, e ngā reo, e ngā karangatanga maha, tēnā pa, i kaha tautoko hoki i tēnei rangahau me āna kaimahi. koutou i te āhuatanga o tēnei pūrongo rangahau, e kīa Ko te tūmanako ia, ka whai take ngā kōrero nei, kia tū nei, He Mangōpare Amohia. Kei te tangi te ngākau ki a tika ai ngā whare maha o te motu, kia tupu ora ai te ta- rātou kua hinga atu, kua hinga mai, i runga i ngā tini ngata, kia tutuki hoki ngā wawata o ngā whānau, o ngā marae o te motu. -

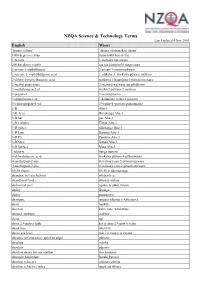

NZQA Science & Technology Terms

NZQA Science & Technology Terms Last Updated 4 Nov 2010 English Māori ‘fitness culture’ ‘ahurea whakapakari tinana’ 1000 degrees celsius mano takiri henekereti 1-hexene 1-waiwaro rua owaro 200 km above (earth) rua rau kiromita ki runga rawa 2-amino-3-methylbutane 2-amino-3-mewarop ūwaro 2–bromo–3–methylbutanoic acid 2–pūkeha–3–waikawa p ūwaro m ēwaro 2-chloro-3-methylbutanoic acid waikawa 2-haum āota-3-pūwaro mewaro 2-methyl propenoate 2-mewaro waiwaro rua p ōhākawa 2-methylpropan-2-ol waihä-2-pöwaro-2-mewaro 2-propanol 2-waih ā p ōwaro 3-chlorobutan-1-ol 3-haum āota waih ā-1-pūwaro 3–chloropropan–1–ol 3–waih ā–1–pōwaro p ūhaum āota 3-D Ahu-3 3-D Area Horahanga Ahu-3 3-D bar pae Ahu-3 3-D Column Tīwae Ahu-3 3-D effect rākeitanga Ahu-3 3-D Line Rārangi Ahu-3 3-D Pie Porohita Ahu-3 3-D Style Kāhua Ahu-3 3-D Surface Mata Ahu-3 3rd party hunga tuatoru 4-chlorobutanoic acid waikawa p ūwaro 4-pūhaum āota 4-methylpent-2-ene 4-waiwaro-rua-2-pēwaro mewaro 4-methylpent-2-yne 4-waiwaro-toru-2-pēwaro mewaro 50-50 chance 50-50 te t ūponotanga abandon, to leave behind whakar ērea abandoned (land) whenua mahue abdominal pain ngau o te puku, k ōpito ability āheinga ability pūmanawa aborigine tangata whenua o Ahitereiria abort haukoti abortion kuka, tahe, whakatahe abound, multiply makuru about mō about 2.4 metres high kei te āhua 2.4 mita te teitei about face tahuri k ē above sea level mai i te mata o te moana abrasive (of character), quick to anger pūtiotio absolute mārika absolute pūrawa absolute desire for one another tara koukoua Absolute Magnitude -

Maori Methods and Indicators for Marine Protection: Ngati Kere

Maori methods and indicators for marine protection I a Kere te ngahuru, ka ngahuru noa atu Ngati Kere interests and It is always harvest time with Ngati Kere expectations for the rohe moana GLOSSARY OF MAORI WORDS GLOSSARY OF MAORI WORDS The following Maori words may occur throughout the text. The The following Maori words may occur throughout the text. The listed pagenumber indicates their first mention and explanation in listed pagenumber indicates their first mention and explanation in context. context. atea / front, 15 pounamu / greenstone, 6 atea / front, 15 pounamu / greenstone, 6 Aotearoa / New Zealand, 5 pouraka / crayfish drop pots, 19 Aotearoa / New Zealand, 5 pouraka / crayfish drop pots, 19 hapu / sub-tribe, 5 pupu / periwinkle, 28 hapu / sub-tribe, 5 pupu / periwinkle, 28 hapuka / groper, 23 punga / stone anchor, 32 hapuka / groper, 23 punga / stone anchor, 32 harakeke / flax, 15 Rahui / period of respect, 19 harakeke / flax, 15 Rahui / period of respect, 19 hinaki / set trap or pot, 28 rangatira / chief, 13 hinaki / set trap or pot, 28 rangatira / chief, 13 hauora / health, 43 rangatiratanga / chieftainship, 6 hauora / health, 43 rangatiratanga / chieftainship, 6 hinu / fat, 23 Rehua / Antares (star), 28 hinu / fat, 23 Rehua / Antares (star), 28 hue / calabash, 32 rohe moana / coastal area, 5 hue / calabash, 32 rohe moana / coastal area, 5 hui / meeting, 9 tahu / method of preserving hui / meeting, 9 tahu / method of preserving inanga / parent whitebait, 24 with fat, 19 inanga / parent whitebait, 24 with fat, 19 iwi / tribe, -

Introducing the Atua Matua Maori Health Framework

Introducing the Atua Matua Maori Health Framework Ihirangi Heke (PhD) Waikato Tainui ! Introduction Connecting health and M"ori concepts of the environment is no small task. Not only has a large amount of M"ori knowledge been lost over the years, but what is retained is sometimes jealously protected and intended for only a select few tribal recipients. Likewise, an attempt to conceptualise the range of M"ori interpretations of health, may well be inappropriate in terms of encouraging iwi (tribal) definitions. Furthermore, many non-M"ori are left wondering how then can they feasibly expect to operate in this domain considering the current status of M"ori engagement with not only health but the environment. There is a way forward. ! The starting point is to develop relationships between iwi and health promoters in a district by district format. While the information will remain the knowledge of those that produced it i.e., iwi M"ori, a sense of sharing and awareness amongst M"ori, in terms of education and language retention, is at the highest point it has been in many years. Due to the M"ori renaissance to reclaim pre-European authentic function, M"ori are making huge gains in reconnecting to environmental knowledge suggesting that increased access to authentic M"ori health approaches may be achievable. One of the outcomes of this renaissance has been the development of an approach that keeps the iwi centric nature of health related knowledge intact i.e., the development of a framework that can be populated with iwi specific interpretations. The approach, known as the Atua Matua Maori Health Framework (Deity to Human Expression) can seamlessly include non-M"ori interpretations of similar environments through M"ori concepts i.e., recognition of the importance of waterways, mountains and star navigation. -

Te Tiriti O Waitangi – Our Treaty

Programme title: Te Tiriti o Waitangi – Our Treaty Years 7–10 Theme Big questions Key competencies ° What is a treaty? ° Using language, symbols, and texts There are many different ways of interpreting and responding to te Tiriti o Waitangi (the ° Why is te Tiriti o Waitangi important? ° Managing self Treaty of Waitangi). ° What are the Treaty’s key ideas? ° Relating to others The Treaty is Aotearoa New Zealand’s ° What are some of the key events ° Thinking founding document. It has shaped our past surrounding the Treaty? and will shape our future. ° What are the Treaty’s main principles? English-medium curriculum Social Sciences ° L4: Understand that events have causes and effects. ° L4: Understand how exploration and innovation create opportunities and challenges for people, places, and environments. ° L5: Understand how people define and seek human rights. ° L5 Understand how te Tiriti o Waitangi is responded to differently by people in different times and places. Visual Arts ° L4: Explore and describe ways in which meanings can be communicated and interpreted in their own and others’ work. English ° L4: Show an increasing understanding of ideas within, across, and beyond texts. ° L4: Integrate sources of information, processes, and strategies confidently to identify, form, and express ideas. Learning intentions (students will be able to): ° Discuss the content of te Tiriti o Waitangi and the differences between the English version and the Māori translation. ° Identify two or more reasons why te Tiriti o Waitangi needed to be created. ° Identify the two main principles of te Tiriti o Waitangi and show how they live on in New Zealand today. -

Māori Issues the General Election Delivered Saura, Bruno

202 the contemporary pacific • 31:1 (2019) otr, Overseas Territories Review. Blog. and Internet news. Tahiti. http://www http://overseasreview.blogspot.com .tahiti-infos.com Pareti, Samisoni. 2017. French in the tntv, Tahiti Nui Télévision (The country House: Pacific Islands Go French. Islands government’s television network). Business, Aug. http://tntv.pf Polynésie Première (French Polynesia pro- TPM, Tahiti-Pacifique Magazine. gram of Outre-mer Première, the French Fortnightly. Tahiti. http://www.tahiti government television network for over- -pacifique.com seas departments and collectivities) http:// United Nations. Question of French http://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/polynesie 2017 Polynesia. Resolution adopted by the Gen- Regnault, Jean-Marc. 2017. Formes eral Assembly on 7 December. UN General et méforme de la présence française en Assembly, 72nd session. a/res/72/101. Océanie. In L’Océanie Convoitée: Actes http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc des colloques, edited by Sémir Al Wardi, .asp?symbol=A/72/PV.66 [accessed 26 Aug Jean-Marc Regnault, and Jean-François 2018] Sabouret, 151–159. Papeete: ‘Api Tahiti; Paris: cnrs Éditions. unesco, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Rival, Yann. 2017. Investissements étrang- 2018. World Heritage List. http://whc ers en Océanie et développement durable: .unesco.org/en/list/ [accessed 26 Aug Projet de ferme aquacole de Hao et projet 2018] du Mahana Beach. In In L’Océanie Con- voitée: Actes des colloques, edited by Sémir Walker, Taaria. 1999. Rurutu: Mémoires Al Wardi, Jean-Marc Regnault, and Jean- d’avenir d’une île Australe. Papeete: François Sabouret, 337–343. Papeete: Haere Po No Tahiti. ‘Api Tahiti; Paris: cnrs Éditions.