Chapter 5 Government and Non- Governmental Involvement in Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representasi Politik Opini Publik Terhadap Pemilukada Sumatra Barat 2010 Pada Koran Singgalang Dan Program Sumbar Satu

Jurnal komunikasi, ISSN 1907-898X Volume 9, Nomor 1, Oktober 2014 Representasi Politik Opini Publik terhadap Pemilukada Sumatra Barat 2010 pada Koran Singgalang dan Program Sumbar Satu Muhammad Thaufan A Prodi Komunikasi, Universitas Andalas, Padang (Mahasiswa doctoral GSID-Nagoya University Japan) Abstract This paper aims to discover political representation of the lokal media namely Harian Singgalang regarding public opinion during the election in West Sumatra Indonesia. Furthermore, the complexity of media power will be discussed through such television program and the newspaper`s headline and special report. By using case study approach and critical discourse analysis of Norman Fairclough in analyzing text, discoursive practice, and socio-cultural practice, it can be noted that political public opinion had been fully articulated in such lokal media representing collaboration actors and institution among media, politicians and lokal people. Political opinion could be sensed in the program “Menuju Sumbar Satu Padang TV” and located in the headlines and special report of Harian Singgalang during April-August 2010. Representation of political opinion in both Padang TV and Singgalang indicated media logic and also vested interested among such media and elites in order to maintain lokal democracy by spreading politically strategic information, persuading the audience, making the myth of good impression in order to win the election. Menuju Sumbar Satu Padang TV has depicted campaign strategy of some governors candidates while headlines and special report of Singgalang have extremely covered all candidates and transformed those dynamic public sphere for political consensus among media, politicians and the audience in promoting lokal democracy in West Sumatra 2010. Key Words : Mass Media, Media Power, Public Opinion, Representation, Democracy Abstrak Tulisan ini menyingkap tabir representasi politis media lokal yaitu Padang TV dan Harian Singgalang terkait opini public dalam proses Pemilukada Sumatera Barat 2010. -

INDO 97 0 1404929731 1 28.Pdf (1.010Mb)

PUNCAK ANDALAS: Fu n c tio n al Regions, Territorial Co alitio ns, a n d the U nlikely Story of O ne W o u l d - be Province Keith Andrew Bettinger1 Since the fall of President Suharto and his authoritarian New Order government in 1998, Indonesia has experienced significant political and administrative transformation. Among the most conspicuous changes are those that have affected the geography of government. The decentralization reforms enacted in the wake of Suharto's forced resignation have not only altered the physical locus of a large spectrum of political and administrative powers, shifting them from Jakarta to outlying regions, but they have also allowed for the redrawing of Indonesia's political-administrative map. Redefining boundaries has been driven by a proliferation of administrative regions, a phenomenon known in Indonesia as pemekaran.2 By late 2013, 202 new districts (kabupaten) and administrative municipalities (kota) had been created, raising the 11 express my gratitude to two anonymous reviewers who provided comments and suggestions that greatly improved this essay. I also gratefully acknowledge the US-Indonesia Society and Mellon Foundation, without whose support this research would not have been possible. Lastly, I gratefully acknowledge comments and suggestions from Ehito Kimura, Krisnawati Suryanata, and Wendy Miles, all at the University of Hawaii. 2 Literally, "blossoming" or "flowering." Indonesia 97 (April 2014) 2 Keith Andrew Bettinger national total to 500. In addition, eight new provinces were created, raising the total to thirty-four. According to the decentralization laws governing pemekaran,3 there are several official justifications that allow for the creation of new regions. -

Regime Change, Democracy and Islam the Case of Indonesia

REGIME CHANGE, DEMOCRACY AND ISLAM THE CASE OF INDONESIA Final Report Islam Research Programme Jakarta March 2013 Disclaimer: The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Islam Research Programme – Jakarta, funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The views presented in this report represent those of the authors and are in no way attributable to the IRP Office or the Ministry CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Kees van Dijk PART 1: SHARIA-BASED LAWS AND REGULATIONS 7 Kees van Dijk SHARIA-BASED LAWS: THE LEGAL POSITION OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN BANTEN AND WEST JAVA 11 Euis Nurlaelawati THE ISLAMIC COURT OF BULUKUMBA AND WOMEN’S ACCESS TO DIVORCE AND POST-DIVORCE RIGHTS 82 Stijn Cornelis van Huis WOMEN IN LOCAL POLITICS: THE BYLAW ON PROSTITUTION IN BANTUL 110 Muhammad Latif Fauzi PART 2: THE INTRODUCTION OF ISLAMIC LAW IN ACEH 133 Kees van Dijk ALTERNATIVES TO SHARIATISM: PROGRESSIVE MUSLIM INTELLECTUALS, FEMINISTS, QUEEERS AND SUFIS IN CONTEMPORARY ACEH 137 Moch Nur Ichwan CULTURAL RESISTANCE TO SHARIATISM IN ACEH 180 Reza Idria STRENGTHENING LOCAL LEADERSHIP. SHARIA, CUSTOMS, AND THE DYNAMICS OF VIGILANTE VIOLENCE IN ACEH 202 David Kloos PART 3: ISLAMIC POLITICAL PARTIES AND SOCIO-RELIGIOUS ORGANIZATIONS 237 Kees van Dijk A STUDY ON THE INTERNAL DYNAMICS OF THE JUSTICE AND WELFARE PARTY (PKS) AND JAMA’AH TARBIYAH 241 Ahmad-Norma Permata THE MOSQUE AS RELIGIOUS SPHERE: LOOKING AT THE CONFLICT OVER AL MUTTAQUN MOSQUE 295 Syaifudin Zuhri ENFORCING RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN INDONESIA: MUSLIM ELITES AND THE AHMADIYAH CONTROVERSY AFTER THE 2001 CIKEUSIK CLASH 322 Bastiaan Scherpen INTRODUCTION Kees van Dijk Islam in Indonesia has long been praised for its tolerance, locally and abroad, by the general public and in academic circles, and by politicians and heads of state. -

West Sumatra and Jambi Natural Disasters

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized West Sumatra and Jambi Natural Disasters andJambi Natural Sumatra West A joint report by the BNPB, Bappenas, and the Provincial and District/City Governments andthe Provincial Bappenas, reportA joint theBNPB, by Damage, Loss and Preliminary LossandPreliminary Damage, of West Sumatra and Jambi and international partners, andJambi andinternational October Sumatra 2009 West of Needs Assessment : Damage, Loss and Preliminary Needs Assessment BADAN NASIONAL PENANGGULANGAN BENCANA The two consecutive earthquakes that hit the provinces of West Sumatra and Jambi on 30 September and 1 October caused widespread damage across the provinces killing over 1,100 people, destroying livelihoods and disrupting economic activity and social conditions. Resulting landslides left scores of houses and villages buried, whilst disrupting power and communication for days. The first of these events was felt throughout Sumatra and Java, in Indonesia, and in neighboring Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. The Government of Indonesia responded immediately by declaring a one-month emergency phase, providing emergency relief funds with a promise of more to follow, and indicating that it welcomed international assistance. In addition, tents, blankets, food, medical personnel, emergency clean water facilities and toilets were provided during the immediate response. The armed forces were also engaged in search and rescue operations and delivering relief aid. National partners, including the Indonesian Red Cross, engaged immediately in emergency response efforts. This report describes the human loss, assessment of the damage to physical assets, the subsequent losses sustained across all economic activities, and the impact of the disaster on the provincial and national economies. -

Making Presidentialism Work: Legislative and Executive Interaction in Indonesian Democracy

Making Presidentialism Work: Legislative and Executive Interaction in Indonesian Democracy Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Djayadi Hanan, M.A. Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: R. William Liddle, Adviser Richard Paul Gunther Goldie Ann Shabad Copyright by Djayadi Hanan 2012 i Abstract This study explores the phenomenon of executive – legislative relations in a new multiparty presidential system. It seeks to understand why, contrary to arguments regarding the dysfunctionality of multi-party presidential systems, Indonesia’s governmental system appears to work reasonably well. Using institutionalism as the main body of theory, in this study I argue that the combination of formal and informal institutions that structure the relationship between the president and the legislature offsets the potential of deadlock and makes the relationship work. The existence of a coalition-minded president, coupled with the tendency to accommodative and consensual behavior on the part of political elites, also contributes to the positive outcome. This study joins the latest studies on multiparty presidentialism in the last two decades, particularly in Latin America, which argue that this type of presidential system can be a successful form of governance. It contributes to several parts of the debate on presidential system scholarship. First, by deploying Weaver and Rockman’s concept of the three tiers of governmental institutions, this study points to the importance of looking more comprehensively at not only the basic institutional design of presidentialism (such as dual legitimacy and rigidity), but also the institutions below the regime level which usually regulate directly the daily practice of legislative – executive relations such as the legislative organizations and the decision making process of the legislature. -

“I Wanted to Run Away” Abusive Dress Codes for Women and Girls in Indonesia WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS “I Wanted to Run Away” Abusive Dress Codes for Women and Girls in Indonesia WATCH “I Wanted to Run Away” Abusive Dress Codes for Women and Girls in Indonesia Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-895-0 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MARCH 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-895-0 “I Wanted to Run Away” Abusive Dress Codes for Women and Girls in Indonesia Glossary ........................................................................................................................... i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 From Pancasila to “Islamic Sharia” .......................................................................................... -

Tilburg University Understanding Human Rights Culture in Indonesia

Tilburg University Understanding Human Rights Culture in Indonesia Regus, Max Publication date: 2017 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Regus, M. (2017). Understanding Human Rights Culture in Indonesia: A Case Study of the Ahmadiyya Minority Group. [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. sep. 2021 Understanding Human Rights Culture in Indonesia: A Case Study of the Ahmadiyya Minority Group Understanding Human Rights Culture in Indonesia: A Case Study of the Ahmadiyya Minority Group PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. E.H.L. Aarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de Ruth First zaal van de Universiteit op maandag 18 december 2017 om 10.00 uur door Maksimus Regus, geboren op 23 september 1973 te Todo, Flores, Indonesië Promotores: Prof. -

“I Wanted to Run Away” Abusive Dress Codes for Women and Girls in Indonesia WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS “I Wanted to Run Away” Abusive Dress Codes for Women and Girls in Indonesia WATCH “I Wanted to Run Away” Abusive Dress Codes for Women and Girls in Indonesia Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-895-0 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MARCH 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-895-0 “I Wanted to Run Away” Abusive Dress Codes for Women and Girls in Indonesia Glossary ........................................................................................................................... i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 From Pancasila to “Islamic Sharia” .......................................................................................... -

IV. State Failure to Protect Religious Minorities from Violence

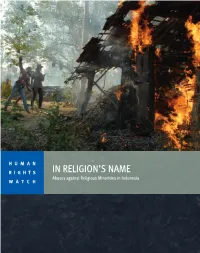

HUMAN RIGHTS IN RELIGION’S NAME Abuses against Religious Minorities in Indonesia WATCH In Religion’s Name Abuses against Religious Minorities in Indonesia Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-992-5 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org FEBRUARY 2013 1-56432-992-5 In Religion’s Name Abuses against Religious Minorities in Indonesia Map .................................................................................................................................... i Glossary ............................................................................................................................ -

Islam, Politics and Change

ISLAM, POLITICS AND CHANGE The Indonesian Experience after the Fall of Suharto Edited by Kees van Dijk and Nico J.G. Kaptein Islam, Politics and Change lucis series ‘debates on islam and society’ Leiden University Press At present important debates about Islam and society take place both in the West and in the Muslim world itself. Academics have considerable expertise on many of the key issues in these debates, which they would like to make available to a larger audience. In its turn, current scholarly research on Islam and Muslim societies is to a certain extent influenced by debates in society. Leiden University has a long tradition in the study of Islam and Muslim societies, past and present, both from a philological and historical perspective and from a social science approach. Its scholars work in an international context, maintaining close ties with colleagues worldwide. The peer reviewed LUCIS series aims at disseminating knowledge on Islam and Muslim societies produced by scholars working at or invited by Leiden University as a contribution to contemporary debates in society. Editors: Léon Buskens Petra Sijpesteijn Editorial board: Maurits Berger Nico J.G. Kaptein Jan Michiel Otto Nikolaos van Dam Baudouin Dupret (Rabat) Marie-Claire Foblets (Leuven) Amalia Zomeño (Madrid) Other titles in this series: David Crawford, Bart Deseyn, Nostalgia for the Present. Ethnography and Photography in a Moroccan Berber Village, 2014. Maurits S. Berger (editor), Applying Shariaʿa in the West. Facts, Fears and the Future of Islamic Rules on Family Relations in the West, 2013. Petra M. Sijpesteijn, Why Arabic?, 2012. Jan Michiel Otto, Hannah Mason (editors), Delicate Debates on Islam. -

Stagnation-On-Freedom-Of-Religion

STAGNATION ON FREEDOM OF RELIGION The Report of Condition on Freedom of Religion/Belief of Indonesia in 2013 Jakarta, February 2014 vi+241 pages 230 mm x155 mm ISBN: 978-6021-8668-7-0 AUTHORS Bonar Tigor Naipospos Halili RESEARCH TEAM Akhol Firdaus (Jawa Timur) Bahrun (Nusa Tenggara Barat) Muhrizal Syahputra (Sumatera Utara) Roni Saputra (Sumatera Barat) Rokhmond Onasis (KalimantanTengah) Andy Irfan Junaidi (Surabaya) Nasrum (Makassar) Yahya Mahmud (MalukuUtara) Rio Rahadian Tuasikal (Jawa Barat) Kahar Muamalsyah (Jawa Tengah) Yosep Dian S (Yogyakarta) Destika Gilang Lestari(Aceh) Mohamad (Kalimantan Barat) Devida (Cirebon) Abdul Khoir (Jakarta) Aminudin Syarif (Jakarta) Dwi A Setiawan (Purworejo) Halili (Yogyakarta) Hilal Safary (Jakarta) Indra Listiantara (Jakarta) LAYOUT Titikoma-Jakarta PUBLISHED BY Pustaka Masyarakat Setara Jl.Danau Gelinggang No.62 Blok C-III Bendungan Hilir, Indonesia 10210 Tel:+6221-70255123 Fax:+6221-5731462 [email protected] [email protected] Foreword This report of Condition on Freedom of Religion/Belief in of Indonesia in 2013 is in form of resume that have been released on January 6, 2014 and just be completely published on April 2014. This hardcopy form-publishing report is part of publication routinity of SETARA Institute which is published annually. As the seventh (7th) report and the report tip of tenure of President Bambang Yudhoyono, who has served two terms of leadership, this report has distinct specificity from the previous reports. Besides to photographing the occured incidents along the year of 2013, through this report SETARA Institute is challenged to trace, to analyze, and to conclude 7 reports that has been published yet during the leadership tenure of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. -

Soeharto's New Order and Its Legacy: Essays in Honour of Harold Crouch

Soeharto’s New Order and its Legacy Essays in honour of Harold Crouch Edited by Edward Aspinall and Greg Fealy Soeharto’s New Order and its Legacy Essays in honour of Harold Crouch Edited by Edward Aspinall and Greg Fealy ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 2 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/soeharto_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Soeharto’s new order and its legacy : essays in honour of Harold Crouch / edited by Edward Aspinall and Greg Fealy. ISBN: 9781921666469 (pbk.) 9781921666476 (pdf) Notes: Includes bibliographical refeßrences. Subjects: Soeharto, 1921-2008 Festschriften--Australia. Indonesia--Politics and government--1966-1998. Indonesia--Economic conditions--1945-1966. Other Authors/Contributors: Aspinall, Edward. Fealy, Greg, 1957- Crouch, Harold, 1940- Dewey Number: 959.8037 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: Photo taken by Edward Aspinall at the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) Congress, Bali, April 2010. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgments. .vii Preface:.Honouring.Harold.Crouch.. ix Jamie Mackie, Edward Aspinall and Greg Fealy Glossary.. xiii Contributors. xix Introduction:.Soeharto’s.New.Order.and.its.Legacy.