Simarouba Monograph 3/1/04 Simarouba Amara, Glauca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Recovery Plan for Quassia Sp

Draft NSW & National Recovery Plan Quassia sp. B (Moonee Quassia) August 2004 © NSW Department of Environment and Conservation, 2004. This work is copyright. However, material presented in this plan may be copied for personal use or published for educational purposes, providing that any extracts are fully acknowledged. Apart from this and any other use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (NSW), no part may be reproduced without prior written permission from NSW Department of Environment and Conservation. NSW Department of Environment and Conservation 43 Bridge Street (PO Box 1967) Hurstville NSW 2220 Tel: 02 9585 6444 www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au Requests for information or comments regarding the recovery program for the Moonee Quassia are best directed to: The Moonee Quassia Recovery Co-ordinator Threatened Species Unit, North East Branch NSW Department of Environment and Conservation Locked Bag 914 Coffs Harbour NSW 2450 Tel: 02 6651 5946 Cover illustrator: Liesel Yates This plan should be cited as follows: NSW Department of Environment and Conservation 2004, Draft Recovery Plan for Quassia sp. B (Moonee Quassia), NSW Department of Environment and Conservation, Hurstville. ISBN 07313 69270 Draft Recovery Plan The Moonee Quassia Draft Recovery Plan for Quassia sp. B (Moonee Quassia). Foreword The New South Wales Government established a new environment agency on 24 September 2003, the Department of Environment and Conservation, which incorporates the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service. Responsibility for the preparation of Recovery Plans now rests with this new department. This document, when finalised, will constitute the formal National and New South Wales State Recovery Plan for Quassia sp. -

Evolution of Agroforestry As a Modern Science

Chapter 2 Evolution of Agroforestry as a Modern Science Jagdish C. Dagar and Vindhya P. Tewari Abstract Agroforestry is as old as agriculture itself. Many of the anecdotal agro- forestry practices, which are time tested and evolved through traditional indigenous knowledge, are still being followed in different agroecological zones. The tradi- tional knowledge and the underlying ecological principles concerning indigenous agroforestry systems around the world have been successfully used in designing the improved systems. Many of them such as improved fallows, homegardens, and park systems have evolved as modern agroforestry systems. During past four decades, agroforestry has come of age and begun to attract the attention of the international scientific community, primarily as a means for sustaining agricultural productivity in marginal lands and solving the second-generation problems such as secondary salinization due to waterlogging and contamination of water resources due to the use of excess nitrogen fertilizers and pesticides. Research efforts have shown that most of the degraded areas including saline, waterlogged, and perturbation ecolo- gies like mine spoils and coastal degraded mangrove areas can be made productive by adopting suitable agroforestry techniques involving highly remunerative compo- nents such as plantation-based farming systems, high-value medicinal and aromatic plants, livestock, fishery, poultry, forest and fruit trees, and vegetables. New con- cepts such as integrated farming systems and urban and peri-urban agroforestry have emerged. Consequently, the knowledge base of agroforestry is being expanded at a rapid pace as illustrated by the increasing number and quality of scientific pub- lications of various forms on different aspects of agroforestry. It is both a challenge and an opportunity to scientific community working in this interdisciplinary field. -

Plants from the Brazilian Traditional Medicine: Species from the Books Of

Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 27 (2017) 388–400 ww w.elsevier.com/locate/bjp Original Article Plants from the Brazilian Traditional Medicine: species from the books of the Polish physician Piotr Czerniewicz (Pedro Luiz Napoleão Chernoviz, 1812–1881) a,c d b,c b,c,∗ Letícia M. Ricardo , Juliana de Paula-Souza , Aretha Andrade , Maria G.L. Brandão a Ministério da Saúde, Departamento de Assistência Farmacêutica e Insumos Estratégicos, Esplanada dos Ministérios, Brasília, DF, Brazil b Centro Especializado em Plantas Aromáticas, Medicinais e Tóxicas, Museu de História Natural e Jardim Botânico, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil c Faculdade de Farmácia, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil d Universidade Federal de São João del Rei, Campus Sete Lagoas, Sete Lagoas, MG, Brazil a b s t r a c t a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: The Brazilian flora is very rich in medicinal plants, and much information about the traditional use of Received 1 October 2016 the Brazilian plants is only available from early literature and we are facing a rapid process of loss of Accepted 10 January 2017 biodiversity. To retrieve data about useful plants registered in the books of the Polish physicist P.L.N. Available online 2 March 2017 Chernoviz, who lived in Brazil for 15 years in the 19th century. The aim is to improve our knowledge about Brazilian plants, and to ensure the benefits of sharing it with potential users. Data about Brazilian Keywords: plants were obtained from six editions of the book Formulary and Medical Guide (Formulário e Guia Historical records Médico), published in 1864, 1874, 1888, 1892, 1897 and 1920. -

APPENDIX K Biological Resource Tables

APPENDIX K Biological Resource Tables APPENDIX K Biology Addendum VASCULAR SPECIES GYMNOSPERMS AND GNETOPHYTES PINACEAE—PINE FAMILY Pinus sp.—pine MONOCOTS ARECACEAE—PALM FAMILY * Archontophoenix cunninghamiana—queen palm * Washingtonia robusta—Washington fan palm EUDICOTS APOCYNACEAE—DOGBANE FAMILY * Nerium oleander—oleander ARALIACEAE—GINSENG FAMILY * Hedera helix—English ivy HAMAMELIDACEAE—WITCH HAZEL FAMILY * Liquidambar sp.—sweet gum MYRTACEAE—MYRTLE FAMILY * Eucalyptus sp.—eucalyptus * Eucalyptus sideroxylon—red ironbark ROSACEAE—ROSE FAMILY * Eriobotrya deflexa—bronze loquat * Rhaphiolepis indica—India hawthorn SCROPHULARIACEAE—FIGWORT FAMILY * Myoporum laetum—myoporum SIMAROUBACEAE—QUASSIA OR SIMAROUBA FAMILY * Ailanthus altissima—tree of heaven ULMACEAE—ELM FAMILY * Ulmus parvifolia—Chinese elm * signifies introduced (non-native) species K-1 February 2016 APPENDIX K (Continued) BIRD Accipiter cooperii—Cooper’s hawk Bombycilla cedrorum—cedar waxwing Corvus brachyrhynchos—American crow Mimus polyglottos—northern mockingbird Spinus psaltria—lesser goldfinch Zenaida macroura—mourning dove Haemorhous mexicanus—house finch K-2 February 2016 APPENDIX K (Continued) Primary Habitat Associations/ Life Form/ Blooming Period/ Elevation Range (feet) Potential to Occur Coastal bluff scrub, coastal dunes, coastal scrub; sandy or gravelly/ annual herb/ Mar–June/ 3-1001 Not expected to occur. The site is outside of the species’ known elevation range and there is no suitable habitat present. Chaparral, coastal scrub, riparian forest, riparian scrub, riparian woodland; sandy, mesic/ perennial Not expected to occur. The site is outside of the species’ known deciduous shrub/ (Feb) May–Sep/ 49-3002 elevation range and there is no suitable habitat present. Chaparral, cismontane woodland, coastal scrub; rocky/ perennial rhizomatous herb/ Feb–June/ 591- Not expected to occur. No suitable habitat present. 3281 Coastal bluff scrub, coastal dunes, coastal scrub, valley and foothill grassland; alkaline or clay/ Not expected to occur. -

Tree Height Growth in a Neotropical Rain Forest

Ecology, 82(5), 2001, pp. 1460±1472 q 2001 by the Ecological Society of America GETTING TO THE CANOPY: TREE HEIGHT GROWTH IN A NEOTROPICAL RAIN FOREST DEBORAH A. CLARK1 AND DAVID B. CLARK1 Department of Biology, University of Missouri±St. Louis, 8001 Natural Bridge Road, St. Louis, Missouri 63121-4499, USA Abstract. There is still limited understanding of the processes underlying forest dy- namics in the world's tropical rain forests, ecosystems of disproportionate importance in terms of global biogeochemistry and biodiversity. Particularly poorly documented are the nature and time scale of upward height growth during regeneration by the tree species in these communities. In this study, we assessed long-term height growth through ontogeny for a diverse group of canopy and emergent tree species in a lowland neotropical rain forest (the La Selva Biological Station, northeastern Costa Rica). Species were evaluated based on annual height measurements of large samples of individuals in all postseedling size classes, over a 16-yr period (.11 000 increments). The study species were seven nonpi- oneers (Minquartia guianensis, Lecythis ampla, Hymenolobium mesoamericanum, Sima- rouba amara, Dipteryx panamensis, Balizia elegans, and Hyeronima alchorneoides) and two pioneers (Cecropia obtusifolia and Cecropia insignis). For each species, inherent height growth capacity was estimated as the mean of the ®ve largest annual height increments (from different individuals) in each juvenile size class (from 50 cm tall to 20 cm in diameter). All species showed marked ontogenetic increases in this measure of height growth potential. At all sizes, there were highly signi®cant differences among species in height growth potential. -

How Rare Is Too Rare to Harvest? Management Challenges Posed by Timber Species Occurring at Low Densities in the Brazilian Amazon

Forest Ecology and Management 256 (2008) 1443–1457 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco How rare is too rare to harvest? Management challenges posed by timber species occurring at low densities in the Brazilian Amazon Mark Schulze a,b,c,*, James Grogan b,d, R. Matthew Landis e, Edson Vidal b,f a School of Forest Resources and Conservation, University of Florida, P.O. Box 110760, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA b Instituto do Homem e Meio Ambiente da Amazoˆnia (IMAZON), R. Domingos Marreiros, no. 2020 Bairro Fa´tima, Bele´m, Para´ 66060-160, Brazil c Instituto Floresta Tropical (IFT), Caixa Postal 13077, Bele´m, Para´ 66040-970, Brazil d Yale University School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, 360 Prospect St., New Haven, CT 06511, USA e Department of Biology, Middlebury College, Middlebury, VT 05753, USA f ESALQ/Universidade de Sa˜o Paulo, Piracicaba, Sa˜o Paulo 13.418-900, Brazil ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Tropical forests are characterized by diverse assemblages of plant and animal species compared to Received 11 September 2007 temperate forests. Corollary to this general rule is that most tree species, whether valued for timber or Received in revised form 28 January 2008 not, occur at low densities (<1 adult tree haÀ1) or may be locally rare. In the Brazilian Amazon, many of Accepted 28 February 2008 the most highly valued timber species occur at extremely low densities yet are intensively harvested with Keywords: little regard for impacts on population structures and dynamics. These include big-leaf mahogany Conservation (Swietenia macrophylla), ipeˆ (Tabebuia serratifolia and Tabebuia impetiginosa), jatoba´ (Hymenaea courbaril), Reduced-impact logging and freijo´ cinza (Cordia goeldiana). -

Woody-Tissue Respiration for Simarouba Amara and Minquartia Guianensis, Two Tropical Wet Forest Trees with Different Growth Habits

Oecologia (1994) 100:213-220 9Springer-Verlag 1994 Michael G. Ryan 9Robert M. Hubbard Deborah A. Clark 9Robert L. Sanford, Jr. Woody-tissue respiration for Simarouba amara and Minquartia guianensis, two tropical wet forest trees with different growth habits Received: 9 February 1994 / Accepted: 26 July 1994 Abstract We measured CO 2 etflux from stems of two maintenance respiration was 54% of the total CO2 efflux tropical wet forest trees, both found in the canopy, but for Simarouba and 82% for Minquartia. For our sam- with very different growth habits. The species were ple, sapwood volume averaged 23% of stem volume Simarouba amara, a fast-growing species associated when weighted by tree size, or 40% with no size weight- with gaps in old-growth forest and abundant in sec- ing. Using these fractions, and a published estimate of ondary forest, and Minquartia guianensis, a slow-grow- aboveground dry-matter production, we estimate the ing species tolerant of low-light conditions in annual cost of woody tissue respiration for primary old-growth forest. Per unit of bole surface, CO2 efflux forest at La Selva to be 220 or 350 gCm-2year -1, averaged 1.24 gmol m -2 s-1 for Simarouba and depending on the assumed sapwood volume. These 0.83gmolm-2s -1 for Minquartia. C02 elttux was costs are estimated to be less than 13% of the gross highly correlated with annual wood production (r 2= production for the forest. 0.65), but only weakly correlated with stem diameter (r 2 = 0.22). We also partitioned the CO2 efttux into the Key words Woody tissue respiration" Maintenance functional components of construction and mainte- respiration 9Tropical wet forest trees 9Carbon balance nance respiration. -

Approved Conservation Advice for Quassia Bidwillii (Quassia)

This Conservation Advice was approved by the Minister/Delegate of the Minister on: 3/07/2008 Approved Conservation Advice (s266B of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999). Approved Conservation Advice for Quassia bidwillii (Quassia) This Conservation Advice has been developed based on the best available information at the time this conservation advice was approved. Description Quassia bidwillii, Family Simaroubaceae, commonly known as Quassia, is a small shrub or tree that grows to about 6 m in height, with red fruit and red flowers from November to March. Its leaves are 4.5–9 cm long, 6–12 mm wide, glabrous (hairless) or sometimes silky to pubescent only on the lower surface, with secondary veins numerous and regularly arranged. Quassia flowers occur in clusters of 1–4, and each flower has 8 to 10 stamens, with filaments densely villous (covered in small hairs) on the outer surface (Harden, 2000). Conservation Status Quassia is listed as vulnerable. This species is eligible for listing as vulnerable under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cwlth) (EPBC Act) as, prior to the commencement of the EPBC Act, it was listed as vulnerable under Schedule 1 of the Endangered Species Protection Act 1992 (Cwlth). Quassia is also listed as vulnerable under Schedule 3 of the Nature Conservation Act 1992 and on the Nature Conservation (Wildlife) Regulation 2006 (Queensland). Distribution and Habitat Quassia is endemic to Queensland and is currently known to occur in several localities between Scawfell Island, near Mackay, and Goomboorian, north of Gympie (QDNR, 2000). Quassia has been confirmed as occurring in at least 40 known sites (QDNR, 2001). -

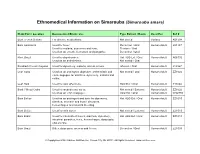

Ethnomedical Information on Simarouba (Simarouba Amara)

Ethnomedical Information on Simarouba (Simarouba amara) Plant Part / Location Documented Ethnic Use Type Extract / Route Used For Ref # Bark French Guiana For diverse medications. Not stated Various K01504 Bark Amazonia Used for fever. Decoction / Oral Human Adult L04137 Used for malaria, dysentery and tonic. Tincture / Oral Used as an emetic, hemostat, and purgative. Decoction / Oral Root Brazil Used to stop diarrhea. Hot H2O Ext / Oral Human Adult A06732 Used as an anthelmintic. Not stated / Oral Rootbark French Guyana Used for dysentery, malaria, and as a tonic. Infusion / Oral Human Adult J12967 Leaf Cuba Used as an astringent, digestive, anthelmintic and Not stated / Oral Human Adult ZZ1022 emmenogogue for diarrhea, dysentery, malaria and colitis. Leaf Haiti Used for skin affections. H2O Ext / Oral Human Adult T13846 Bark / Wood Cuba Used for wounds and sores. Not stated / External Human Adult ZZ1022 Used as an emmenagogue. H2O Ext / Oral Human Adult W02855 Bark Belize Used as an astringent and tonic for dysentery, Hot H2O Ext / Oral Human Adult ZZ1019 diarrhea, stomach and bowel disorders, hemorrhages and internal bleeding. Bark Belize Used for skin sores. Not stated / External Human Adult ZZ1019 Bark Brazil Used for intermittent fevers, diarrhea, dysentery, Hot H2O Ext / Oral Human Adult ZZ1013 intestinal parasites, tonic, hemorrhages, dyspepsia, and anemia. Bark Brazil Bitter, dyspepsia, anemia and fevers. Decoction / Oral Human Adult ZZ1099 © Copyrighted 2004. Raintree Nutrition, Inc. Carson City, NV 89701. All Rights Reserved. www.rain-tree.com Plant Part / Location Documented Ethnic Use Type Extract / Route Used For Ref # Bark + Root Brazil Used for bleeding diarrhea. Decoction / Oral Human Adult ZZ1099 Bark Brazil Used for acute and chronic dysentery, bitter tonic, Infusion / Oral Human Adult ZZ1007 febrifuge, diarrhea, inappetite, and dyspepsia. -

INSECTICIDAL ACTIVITY of NEEM, PYRETHRUM and QUASSIA EXTRACTS and THEIR MIXTURES AGAINST DIAMONDBACK MOTH LARVAE (Plutella Xylostella L.)

MENDELNET 2016 INSECTICIDAL ACTIVITY OF NEEM, PYRETHRUM AND QUASSIA EXTRACTS AND THEIR MIXTURES AGAINST DIAMONDBACK MOTH LARVAE (Plutella xylostella L.) NAMBE JABABU, TOMAS KOPTA, ROBERT POKLUDA Department of Vegetable Science and Floriculture Mendel University in Brno Valticka 337, 69144 Lednice CZECH REPUBLIC [email protected] Abstract: The diamondback moth is known globally by many as the most destructive and economically important insect pest of cruciferous crops. It is also known to have developed resistance to numerous synthetic insecticides including those with newer active ingredients (Shelton et al. 2008); and this has triggered the development of alternative measures, including botanical insecticides (Oyedokun et al. 2011). The aim of this study was to evaluate the toxic effect of Azadirachta indica, Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium and Quassia amara extracts and their mixtures on the diamondback moth larvae; in an attempt to find a superior mixture with more than one major active ingredient for the control of diamondback moth. The study consisted of two separate experiments; a feeding test, and a tarsal contact test. Mortality was recorded at 24, 48 and 72-h intervals from the start of the study. Varying levels of mortalities was recorded in both tests; mortalities ranged between 2–58% and 8% to 76% for the feeding test and the tarsal contact experiment respectively. In both experiments, the highest mortality was recorded in the first 24h and in formulations with the highest concentration. For the feeding test, Pyrethrins, Azadirachtin + Pyrethrins and Azadirachtin + Pyrethrins + Quassin extract/extract mixtures, produced the best effect; with Pyrethrins recording a 54% total mortality count, Azadirachtin + Pyrethrins combination producing a 48% mortality count and a 58% mortality count from Azadirachtin + Pyrethrins + Quassin extract combination. -

A Preliminary List of the Vascular Plants and Wildlife at the Village Of

A Floristic Evaluation of the Natural Plant Communities and Grounds Occurring at The Key West Botanical Garden, Stock Island, Monroe County, Florida Steven W. Woodmansee [email protected] January 20, 2006 Submitted by The Institute for Regional Conservation 22601 S.W. 152 Avenue, Miami, Florida 33170 George D. Gann, Executive Director Submitted to CarolAnn Sharkey Key West Botanical Garden 5210 College Road Key West, Florida 33040 and Kate Marks Heritage Preservation 1012 14th Street, NW, Suite 1200 Washington DC 20005 Introduction The Key West Botanical Garden (KWBG) is located at 5210 College Road on Stock Island, Monroe County, Florida. It is a 7.5 acre conservation area, owned by the City of Key West. The KWBG requested that The Institute for Regional Conservation (IRC) conduct a floristic evaluation of its natural areas and grounds and to provide recommendations. Study Design On August 9-10, 2005 an inventory of all vascular plants was conducted at the KWBG. All areas of the KWBG were visited, including the newly acquired property to the south. Special attention was paid toward the remnant natural habitats. A preliminary plant list was established. Plant taxonomy generally follows Wunderlin (1998) and Bailey et al. (1976). Results Five distinct habitats were recorded for the KWBG. Two of which are human altered and are artificial being classified as developed upland and modified wetland. In addition, three natural habitats are found at the KWBG. They are coastal berm (here termed buttonwood hammock), rockland hammock, and tidal swamp habitats. Developed and Modified Habitats Garden and Developed Upland Areas The developed upland portions include the maintained garden areas as well as the cleared parking areas, building edges, and paths. -

Obdiplostemony: the Occurrence of a Transitional Stage Linking Robust Flower Configurations

Annals of Botany 117: 709–724, 2016 doi:10.1093/aob/mcw017, available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org VIEWPOINT: PART OF A SPECIAL ISSUE ON DEVELOPMENTAL ROBUSTNESS AND SPECIES DIVERSITY Obdiplostemony: the occurrence of a transitional stage linking robust flower configurations Louis Ronse De Craene1* and Kester Bull-Herenu~ 2,3,4 1Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 2Departamento de Ecologıa, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, 3 4 Santiago, Chile, Escuela de Pedagogıa en Biologıa y Ciencias, Universidad Central de Chile and Fundacion Flores, Ministro Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/aob/article/117/5/709/1742492 by guest on 24 December 2020 Carvajal 30, Santiago, Chile * For correspondence. E-mail [email protected] Received: 17 July 2015 Returned for revision: 1 September 2015 Accepted: 23 December 2015 Published electronically: 24 March 2016 Background and Aims Obdiplostemony has long been a controversial condition as it diverges from diploste- mony found among most core eudicot orders by the more external insertion of the alternisepalous stamens. In this paper we review the definition and occurrence of obdiplostemony, and analyse how the condition has impacted on floral diversification and species evolution. Key Results Obdiplostemony represents an amalgamation of at least five different floral developmental pathways, all of them leading to the external positioning of the alternisepalous stamen whorl within a two-whorled androe- cium. In secondary obdiplostemony the antesepalous stamens arise before the alternisepalous stamens. The position of alternisepalous stamens at maturity is more external due to subtle shifts of stamens linked to a weakening of the alternisepalous sector including stamen and petal (type I), alternisepalous stamens arising de facto externally of antesepalous stamens (type II) or alternisepalous stamens shifting outside due to the sterilization of antesepalous sta- mens (type III: Sapotaceae).