1608525368951-0.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peoples Under Threat 2017 Briefing

Peoples under Threat 2017 Killings in the no-access zone www.peoplesunderthreat.org Peoples under Threat 2017: fact-based assessment’, as well as ‘claims that insecure Killings in the no-access zone conditions make it impossible to give ... access’. In Vulnerable peoples are living at deadly risk in a many cases, access delayed – while security operations growing number of no-go zones around the world. are ongoing, for example – is access denied. The 2017 release of Peoples under Threat highlights What is happening in the no-access zone? Where how lack of access from the outside world allows official monitors and investigators cannot enter, local killing to be perpetrated unchecked in disputed NGOs and civilian activists have nonetheless raised territories, militarized enclaves and, in some cases, the alarm and published evidence of gross violations: whole countries. arbitrary detention, torture and, in the case of those This is the 12th year that the Peoples under Threat country situations at the very top of the index, mass index has identified those country situations around killing. In one situation after another, violations the world where communities face the greatest risk of are targeted at communities on ethnic, religious or genocide, mass killing or systematic violent repression. sectarian grounds. Based on current indicators from authoritative sources The most pressing problems of access are described (see ‘How is Peoples under Threat calculated?’), the in the commentary below on individual states. But in index provides early warning of potential future mass addition to those we highlight here, it should be noted atrocities. that the challenge of international access also applies In June 2017 the United Nations (UN) High to a number of territories where the overall threat Commissioner for Human Rights reiterated his levels may be lower, but where particular populations alarm at the refusal of several states to grant access remain highly vulnerable. -

M a R C H 2 0 , 1 9

The Magazine of Metalworking and Metalproducing MARCH 20, 1944 Volume 114— Number 12 Women workers operating centerless grinders in plant of Wyckoff Drawn Steel C o . P a g e 8 0 EDITORIAL STAFF E . L . S h a n e r NEWS Editor-in-Chief E . C . K reutzberg “Jumping the Gun” is Major Civilian Goods Problem 49 E ditor WPB officials seek fair competition in reconversion period W m. M . R o o n e y I r w i n H . S u c h News Editor Engineering Editor What’s Ahead for the Metalworking Industry? 67 J . D . K n o x G u y H u b b a r d S t e e l ’s survey reveals industry’s views on reconversion problems Steel Plant Editor Machine Tool E ditor A rthur F. M acconochie Present, Past and Pending 51 Decentralization 60 Contributing Editor Surplus Materials 52 Ferroalloys 61 D. S. C adot A rt Editor Railroads 53 WPB-OPA 62 Iron O r e ....................................... 54 Men of Industry 64 Associate Editors Steel Prices .................................. 55 Obituaries 66 G. H. M anlovr W . J. Cam pbell G. W. B i r d s a l l F . R , B r i g g s Contracting ................................ 56 Women at Work 80 New York, B. K . P r i c e , L. E . B r o w n e Pittsburgh, R . L. H a r t f o r d Chicago, E . F . R o s s Detroit, A. H. A llen W ashington, L . M . -

The Raid on Gaborone, June 14, 1985: a Memorial

The Raid on Gaborone, June 14, 1985: A memorial http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.BOTHISP104 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The Raid on Gaborone, June 14, 1985: A memorial Author/Creator Nyelele, Libero; Drake, Ellen Publisher Libero Nyelele and Ellen Drake Date 1985-14-06 Resource type Pamphlets Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Botswana Coverage (temporal) 1985-1986 Source Northwestern University Libraries, 968.1103.N994r Description Table of Contents: The Raid; The Victims: the Dead; The Injured; Property Damage; Epilogue; Poem: Explosion of Fire; Lithograph: the Day After; Post Script Format extent 40 (length/size) http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.BOTHISP104 http://www.aluka.org 6g 6g M, I THE RA ON GABORONE: JUNE 14 l.985 by Libero Nyelele and Ellen Drake n 0**. -

For Use by the Author Only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV Afrika-Studiecentrum Series

David Livingstone and the Myth of African Poverty and Disease For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV Afrika-Studiecentrum Series Series Editors Lungisile Ntsebeza (University of Cape Town, South Africa) Harry Wels (VU University Amsterdam, The Netherlands, African Studies Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands and University of the Western Cape, South Africa) Editorial Board Emmanuel Akyeampong (Harvard University, USA) Akosua Adomako Ampofo (University of Ghana, Legon) Fatima Harrak (University of Mohammed V, Morocco) Francis Nyamnjoh (University of Cape Town, South Africa) Robert Ross (Leiden University, The Netherlands) VOLUME 35 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/asc For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV David Livingstone and the Myth of African Poverty and Disease A Close Examination of His Writing on the Pre-colonial Era By Sjoerd Rijpma LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV © Translation: Mrs R. van Stolk. The original text of this story was written by Sjoerd Rijpma (pronounced: Rypma) in Dutch—according to David Livingstone ‘of all languages the nastiest. It is good only for oxen’ (Livingstone, Family Letters 1841–1856, vol. 1, ed. I. Schapera (London: Chatto and Windus, 1959), 190). This is not the reason it has been translated into English. Cover illustration: A young African herd boy sitting on a large ox. The photograph belongs to a series of Church of Scotland Foreign Missions Committee lantern slides relating to David Livingstone. Photographer unknown. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rijpma, Sjoerd, 1931–2015, author. David Livingstone and the myth of African poverty and disease : a close examination of his writing on the pre-colonial era / by Sjoerd Rijpma. -

Federalist Outlook Through Some Combination of Tax Increases, Spend- to Federally Funded, State-Administered Programs

No. 17 May 2003 Washington and the States: Segregation Now By Michael S. Greve The states are broke. The economic recession and the attendant collapse of state revenues, the continuing costs of state programs created during the boom years, and the spiraling costs of federal mandates will force most states to enact massive tax increases and budget cuts. Predictably, the states are demanding more money from Washington, D.C. That, however, is the wrong prescription. The correct approach is to segregate state from federal functions. This Outlook provides principles and practical reform proposals for the most critical programs—Medicaid and education. The Fiscal Crisis of the States billion deficit (over 35 percent of its total bud- get) to the lingering costs of its harebrained For the current fiscal year, the states face a com- energy policies. That said, the states’ fiscal crisis bined deficit of over $30 billion. Having exhausted is in fact systemic. Like the proverbial canary, it gimmicks, easy fixes, and tobacco payments in last signals a grave problem in federalism’s subter- year’s budget cycle, the states will have to cover that ranean architecture—the lack of transparency, sum and next year’s estimated $80 billion deficit accountability, and responsibility that is endemic Federalist Outlook through some combination of tax increases, spend- to federally funded, state-administered programs. ing cuts, and higher federal transfer payments—the Instead of silencing the bird by stuffing money governors’ preferred option. down its throat, we should disentangle federal Each economic downturn produces the same responsibilities from state and local ones. -

University of Zimbabwe Departments of Economics Law Political and Administrative Studies

UNIVERSITY OF ZIMBABWE DEPARTMENTS OF ECONOMICS LAW POLITICAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE STUDIES Paper 1 FRONTLINE STATES AND SOUTHERN AFRICAN REGIONAL RESPONSE fFO SOUTH AFRICAN ARMED AGRESSION by K Makamure and R Loewenson University of Zimbabwe INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR SERIES SEMINAR ON SOUTHERN AFRICAN RESPONSES TO IMPERIALISM ii HARARE 22-24 APRIL 1987 FRONTLINE STATES .AND SOUTHERN AFRICAN REGIONAL .RESPONSE TO SOUTH' AFRICAN ARMED AGGRESS ION - - A ' SIt Jd T' IN ’ WAR AND STRATEGY IN SOUTHERN AFRICA by CUES K. MAKAMURE AND R .LOEWENSON WAR AS A CONTINUATION OF POLITICS BY OTHER MEANS "War is the highest form of struggle for resolving contradictions, when they have developed to a certain stage, between classes, nations , states, or political groups, and it has existed ever since the emergence of private property and of classes ."(1) This great classic statement sums up the historical and dialectical materialist, conception of war and armed struggle held and developed by the great proletarian leaders and theoreticians of the world communist movement namely: Marx, Engels and Lenin. This underslanding of war as a phenomenon was also similarly understood by the early 19th Century German military scholar, Karl von ^Clausewitz who in his book, "On War" , defined war as, "an act of violence intended to compel our opponent to fulfill our will." Clausewitz further classified war as " belonging to the province of social life. It is a conflict of great interests which is settled by bloodshed, and only in that is it different from others." In addition, Clausewitz also viewed political aims as the end and war as the means and in stressing this dialectical link he wrote: t "War is nothing else than the continuation of state policy by different means." On this he elaborated thus: "War is not only a political act but a real political instrument, a continuation of political transactions, an accomplishment of these by different means. -

South Africa & Botswana Tour Booklet

YARM SCHOOL RUGBY TOUR South Africa and Botswana 2013 CONTENTS PAGE 2 Table of Contents 3 Code of Conduct 4 - 8 Rugby Tour Final Information 9 Flight Information 10 - 22 Tour itinerary 23 - 26 Hotel Information 27 - 37 South Africa Fact Sheets 38 - 45 Botswana Fact Sheets 46 - 50 Team Sheets 2 Code of Conduct Throughout the tour it is important for the entire tour party to remember that at all times they will be acting as ambassadors for Yarm School during the whole trip. Naturally, this includes time spent at airports, on the journeys, with host families, during free time as well as during games. People will judge the school and England more generally, on our appearance, demeanour and attitude. We expect pupils to be smartly turned out at all times, to be proud to be on tour with the School and to be keen to make a favourable impression. Normal School rules will apply. That is to say that we expect no foul language; alcohol, smoking, drugs and pornography remain banned as they are in School and pupils should remember that they are on a School trip with their teachers. It is important that pupils and parents understand that any serious transgression of these expectations and rules will result in disciplinary consequences. We hope very much that it will not be necessary to discipline tourists, either on the trip or when the party returns to School. Very serious misbehaviour could result in a pupil being sent back at parental expense. It goes without saying that nobody on the trip wants to exercise this right. -

Black Consciousness and the Politics of Writing the Nation in South Africa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository Black Consciousness and the Politics of Writing the Nation in South Africa by Thomas William Penfold A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of African Studies and Anthropology School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2013 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Since the transition from apartheid, there has been much discussion of the possibilities for the emergence of a truly ‘national’ literature in South Africa. This thesis joins the debate by arguing that Black Consciousness, a movement that began in the late 1960s, provided the intellectual framework both for understanding how a national culture would develop and for recognising it when it emerged. Black Consciousness posited a South Africa where formerly competing cultures sat comfortably together. This thesis explores whether such cultural equality has been achieved. Does contemporary literature harmoniously deploy different cultural idioms simultaneously? By analysing Black writing, mainly poetry, from the 1970s through to the present, the study traces the stages of development preceding the emergence of a possible ‘national’ literature and argues that the dominant art versus politics binary needs to be reconsidered. -

Aloe in Angola (Asphodelaceae: Alooideae)

Bothalia 39,1: 19–35 (2009) Aloe in Angola (Asphodelaceae: Alooideae) R.R. KLOPPER*, S. MATOS**, E. FIGUEIREDO*** and G.F. SMITH*+ Keywords: Aloe L., Angola, Asphodelaceae, fl ora ABSTRACT Botanical exploration of Angola was virtually impossible during the almost three-decade-long civil war. With more areas becoming accessible, there is, however, a revived interest in the fl ora of this country. A total of 27 members of the genus Aloe L. have been recorded for Angola. It is not unlikely that new taxa will be discovered, and that the distribution ranges of oth- ers will be expanded now that botanical exploration in Angola has resumed. This manuscript provides a complete taxonomic treatment of the known Aloe taxa in Angola. It includes, amongst other information, identifi cation keys, descriptions and distribution maps. INTRODUCTION The country has two distinct seasons: the rainy season from October to May, with average coastal temperatures The Republic of Angola covers an area of ± of around 21ºC and the dryer season with lower average 1 246 700 km² in southwest-central Africa. Its west- coastal temperatures of around 16ºC and mist or Cacimbo ern boundary is 1 650 km along the Atlantic Ocean and from June to September. The heaviest rains occur in April it is bordered by Namibia in the south, the Democratic and are accompanied by violent storms. Rainfall along the Republic of Congo in the north and northeast, and Zam- coast is high and gradually decreases from 800 mm in the bia in the east. The detached province of Cabinda has north to 50 mm in the south. -

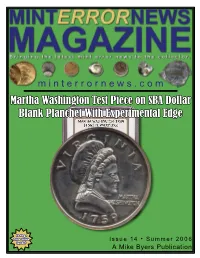

Martha Washington Test Piece on SBA Dollar Blank Planchet with Experimental Edge

TM minterrornews.com Martha Washington Test Piece on SBA Dollar Blank Planchet With Experimental Edge 18 Page Price Guide Issue 14 • Summer 2006 Inside! A Mike Byers Publication Al’s Coins Dealer in Mint Errors and Currency Errors alscoins.com pecializing in Mint Errors and Currency S Errors for 25 years. Visit my website to see a diverse group of type, modern mint and major currency errors. We also handle regular U.S. and World coins. I’m a member of CONECA and the American Numismatic Association. I deal with major Mint Error Dealers and have an excellent standing with eBay. Check out my show schedule to see which major shows I will be attending. I solicit want lists and will locate the Mint Errors of your dreams. Al’s Coins P.O. Box 147 National City, CA 91951-0147 Phone: (619) 442-3728 Fax: (619) 442-3693 e-mail: [email protected] Mint Error News Magazine Issue 14 • S u m m e r 2 0 0 6 Issue 14 • Summer 2006 Publisher & Editor Mike Byers - Table of Contents - Design & Layout Sam Rhazi Contributing Editors Mike Byers’ Welcome 4 Tim Bullard Off-Center Errors 5 Allan Levy Off-Metal & Clad Layer Split-Off Errors 16 Contributing Writers Heritage Galleries & Auctioneers Buffalo 5¢“Speared Bison” & Wisconsin 25¢ “Extra Leaves” 20 Rich Schemmer • Bill Snyder Other Mint Errors 22 Fred Weinberg Advertising Martha Washington Test Piece Struck on SBA Dollar Blank 27 The ad space is sold out. Please e-mail 2001-S Proof Rhode Island Quarter Double Struck in Silver 29 [email protected] to be added to the waiting list. -

Christus Liberator : an Outline Study of Africa

HRIS 113 I™'*' N OUTLINE STUDY O> i~ AFRICA .Jf?\. ).J - 1 1 ' \ /' '-kJ C J * DEC 8 1906 *' BV 3500 .P37 1906 Parsons, Ellen C, 1844- Christus liberator CHRISTUS LIBERATOR UNITED STUDY OF MISSIONS. VIA CHRISTI. An Introduction to the Study of Missions. Louise Manning Hodgkins. LUX CHRISTI. An Outline Study of India. Caroline Atwater Mason. REX CHRISTUS. An Outline Study of China. Arthur H. Smith. DUX CHRISTUS. An Outline Study of Japan. William Elliot Griffis. CHRISTUS LIBERATOR. An Outline Study of Africa. Ellen C. Parsons. OTHER VOLUMES IN PREPARATION. CHRISTUS LIBERATOR AN OUTLINE STUDY OF AFRICA BY ELLEN C. PARSONS, M.A. INTKODUCTION BY SIR HARRY H. JOHNSTON, K.C.B. AUTHOB OF "BKITIBH CENTBAL AFEICA," ETC. WeiM gork THE MACMILLAN COMPANY LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., Ltd. 1906 All rights reserved COPTEIGHT, 3905, By the MACMILLAN COMPANT. Set up and electrotyped. Published July, 1905. Reprinted January, April, 1906. PUBLISHED FOE THE CENTRAL COMMITTEE ON THE UNITED STUDY OF MISSIONS. J. 8. Cushing- &. Co. ~ Berwick «fe Smith Co. Norwood, Mass., U.S.A. STATEMENT OF THE CENTRAL COMMITTEE ON THE UNITED STUDY OF MISSIONS Increasing interest in the United Study Series and con- tinued sales ol: the four volumes already issued assure a welcome for the fifth volume from an appreciative constitu- ency. Since the publication of the first of the series in 1901, the sales of "Via Christi : An Introduction to the " Study of Missions," of Lux Christi : An Outline Study of India," "Rex Cbristus : An Outline Study of China," and " Dux Christus : An Outline Study of Japan, " have amounted to a total of 19-4,000 copies. -

Index to Livingstone's Journal

INDEX LIVINGSTONE'S JOURNAL , 1857 INDEX LIVINGSTONE'S JOURNAL. 8* to Part of page 8, and the whole of pages and 8| , appended this, are additional to the Third Edition of Dr. Livingstone's Journal. ; ;; 73? INDEX. AHREU. ANTKLOPK. BABISA. Abrf.u, Cypriano di, assists Dr. Amaral, General, law enforced by, of life, 256; skins, Matiamvo's Livingstone to cross the Quango, 432. tribute, 479. 365, 366; kindness and hospitality Amaryllis, toxicaria, use, served by Ant-hills, huge, on the banks of the shown by, to Dr. Livingstone, its silky down, 112. Chobe, 176; fertility of, 203; 366, 307 ; death of his stepfather, Ambaca, Dr. Livingstone's guide edible mushrooms growing on, his debts, 440. to, his character and behaviour, 285 ; the chief garden ground of Abutua, the ancient kingdom of, a 375, 376; arrival at the village the Batoka, 551 ; mushrooms on, gold district, 637. of, 381 ; kind reception of the 625. Adanson, longevity ascribed by, to Commandant, 382 ; population of Antidotes to the Ngotuane poison, the 162. the district, 382 arrival at, 418 to Mowana, ; ; 113; the N'gwa poison, 171; Aerolites observed by Dr. Living- departure from, 419. to venomous bites, 172. stone, 596. Ambakistas, inhabitants of Am- Antony, St., image of, belonging to of, iEsop, table proof of his African baca, 375 ; good education of, half-caste soldiers, 367. birth, 43. 441, 442. Antonio, St., convent of, 397. Africa, strong vitality of native Ambonda, the family of the Mam- Ants, black, able to distil water, 21, races in, 115; permanence of bari, 218 ; situation of their 22; large black, emitting a pun- tribes in, 422.