Federalist Outlook Through Some Combination of Tax Increases, Spend- to Federally Funded, State-Administered Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M a R C H 2 0 , 1 9

The Magazine of Metalworking and Metalproducing MARCH 20, 1944 Volume 114— Number 12 Women workers operating centerless grinders in plant of Wyckoff Drawn Steel C o . P a g e 8 0 EDITORIAL STAFF E . L . S h a n e r NEWS Editor-in-Chief E . C . K reutzberg “Jumping the Gun” is Major Civilian Goods Problem 49 E ditor WPB officials seek fair competition in reconversion period W m. M . R o o n e y I r w i n H . S u c h News Editor Engineering Editor What’s Ahead for the Metalworking Industry? 67 J . D . K n o x G u y H u b b a r d S t e e l ’s survey reveals industry’s views on reconversion problems Steel Plant Editor Machine Tool E ditor A rthur F. M acconochie Present, Past and Pending 51 Decentralization 60 Contributing Editor Surplus Materials 52 Ferroalloys 61 D. S. C adot A rt Editor Railroads 53 WPB-OPA 62 Iron O r e ....................................... 54 Men of Industry 64 Associate Editors Steel Prices .................................. 55 Obituaries 66 G. H. M anlovr W . J. Cam pbell G. W. B i r d s a l l F . R , B r i g g s Contracting ................................ 56 Women at Work 80 New York, B. K . P r i c e , L. E . B r o w n e Pittsburgh, R . L. H a r t f o r d Chicago, E . F . R o s s Detroit, A. H. A llen W ashington, L . M . -

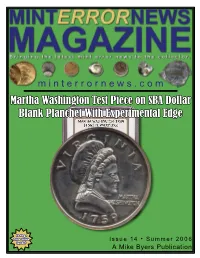

Martha Washington Test Piece on SBA Dollar Blank Planchet with Experimental Edge

TM minterrornews.com Martha Washington Test Piece on SBA Dollar Blank Planchet With Experimental Edge 18 Page Price Guide Issue 14 • Summer 2006 Inside! A Mike Byers Publication Al’s Coins Dealer in Mint Errors and Currency Errors alscoins.com pecializing in Mint Errors and Currency S Errors for 25 years. Visit my website to see a diverse group of type, modern mint and major currency errors. We also handle regular U.S. and World coins. I’m a member of CONECA and the American Numismatic Association. I deal with major Mint Error Dealers and have an excellent standing with eBay. Check out my show schedule to see which major shows I will be attending. I solicit want lists and will locate the Mint Errors of your dreams. Al’s Coins P.O. Box 147 National City, CA 91951-0147 Phone: (619) 442-3728 Fax: (619) 442-3693 e-mail: [email protected] Mint Error News Magazine Issue 14 • S u m m e r 2 0 0 6 Issue 14 • Summer 2006 Publisher & Editor Mike Byers - Table of Contents - Design & Layout Sam Rhazi Contributing Editors Mike Byers’ Welcome 4 Tim Bullard Off-Center Errors 5 Allan Levy Off-Metal & Clad Layer Split-Off Errors 16 Contributing Writers Heritage Galleries & Auctioneers Buffalo 5¢“Speared Bison” & Wisconsin 25¢ “Extra Leaves” 20 Rich Schemmer • Bill Snyder Other Mint Errors 22 Fred Weinberg Advertising Martha Washington Test Piece Struck on SBA Dollar Blank 27 The ad space is sold out. Please e-mail 2001-S Proof Rhode Island Quarter Double Struck in Silver 29 [email protected] to be added to the waiting list. -

Preliminary Metallogenic Map of North America: a Numerical Listing of Deposits

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 858-A Preliminary Metallogenic Map of North America: A Numerical Listing of Deposits Preliminary Metallogenic Map of North America: A Numerical Listing of Deposits By Philip W. Guild GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 858-A 1981 United States Department of the Interior JAMES G. WATT, Secretary Geological Survey Dallas L. Peck, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 81-600156 Free on application to Distribution Branch, Text Products Section, U. S. Geological Survey, 604 South Pickett Street, Alexandria, VA 22304 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract_----------------------------------------------------- A1 Numerical listing of deposits-Continued Introduction__________________________________________________ 1 Mexico-Continued The map------------------------------------------------------ 2 San Luis Potos1 ------------------------------------ A55 Base map------------------------------------------------ 2 Sinaloa______________________________________________ 55 Geologic/structural background----------------------- 2 Sonora---------------------------------------------- 56 Mineral deposits---------------------------------------- 3 Tamaulipas_________________________________________ 58 Spot symbols--------------------------------------- 3 Vera Cruz ------------------------------------------ 58 Districts -------------------------------------------- 6 Zacatecas ------------------------------------------- 58 Mineralogic nature -------------------------------- 6 Nicaragua ----------------------------------------------- 59 Identification -

NGC Certifies 1804 $2½ Capped Bust Double Struck First Strike Off-Center

TM minterrornews.com NGC Certifies 1804 $2½ Capped Bust Double Struck First Strike Off-Center 18 Page Price Guide I s s u e 17 • Spring 2007 Inside! A Mike Byers Publication Al’s Coins Dealer in Mint Errors and Currency Errors alscoins.com pecializing in Mint Errors and Currency SErrors for 25 years. Visit my website to see a diverse group of type, modern mint and major currency errors. We also handle regular U.S. and World coins. I’m a member of CONECA and the American Numismatic Association. I deal with major Mint Error Dealers and have an excellent standing with eBay. Check out my show schedule to see which major shows I will be attending. I solicit want lists and will locate the Mint Errors of your dreams. Al’s Coins P.O. Box 147 National City, CA 91951-0147 Phone: (619) 442-3728 Fax: (619) 442-3693 e-mail: [email protected] Mint Error News Magazine Issue 17 • S p r i n g 2 0 0 7 Al’s Coins Issue 17 • Spring 2007 Dealer in Mint Errors and Currency Errors Publisher & Editor - Table of Contents - alscoins.com Mike Byers Design & Layout Mike Byers’ Welcome 4 Sam Rhazi Off-Center Errors 5 Off-Metal & Clad Layer Split-Off Errors 17 Contributing Editors Buffalo 5¢ “Speared Bison” & WI 25¢ “Extra Leaves” 22 Ronnah Johnson Waff led Coins 24 Allan Levy Doubled Dies 25 Contributing Writers NGC Certifies 1804 $2½ Capped Bust Double Struck Off-Center 27 Heritage Galleries & Auctioneers Mike Diamond • Rich Schemmer Morgan Dollar Reverse Die From San Francisco Mint 30 Daniel Schneider • Bill Snyder 1859 Indian Head Cent Deep Obverse Die Cap 31 Fred Weinberg 1862 Indian Head Cent Deep Obverse Die Cap 33 Advertising Spectacular Mint Errors Sell in Recent Heritage Galleries Auctions 35 The ad space is sold out. -

D Time=Of=Day Pricing in the United States Volume 2: Appendices and Case Studies

Q Evidence on ~~d Time=of=Day Pricing in the United States Volume 2: Appendices and Case Studies May 1984 Evidence on Time=of=Day Pricing in the United States Volume 2: Appendices and Case Studies May 1984 Prepared by Robert Cervero, with research assistance from Mark Hansen, Therese Watkins, and Joel Markowitz Institute of Urban and Regional Development University of California Berkeley, California 94720 Prepared for Office of Management Research and Transit Services Urban Mass Transportation Administration U.S. Department of Transportation Washington, D.C. 20590 In cooperation with Technology Sharing Program Office of the Secretary of Transportation Washington, D.C. 20590 DOT-I-84-40 Forward TtIisis the companion volume to the research report on Evidence on —.Time-of-~ Transit Pricing ——in the United States. This volume serves ~ an expanded appendix to the Volume 1 report, principally providing detailed case-by-case summaries on experiences with time-of-day transit pricing to date. It provides the interested reader with more in-depth background information on the reasons for adopting time-of-day pricing, the impacts recorded to date, implementation issues, a national survey of transit officials, along with a theoretical summary of the time-of- day pricing concept. Appendix I presents thirty-two individual case study summaries on time-of-day transit pricing experiences. Attention focuses on each rationale for adopting time-of-day pricing, trends and impacts associ- ated with the fare programs, and assorted implementation issues. Per- formance data and statistics are generally provided for each case study. Appendix II presents the theory of peak-load and time-of-day pric- ing, in particular as it bears on the American transit industry. -

Mineral Resources of Washington with STATISTICS for 1922

STATE OF WASHINGTON Department of Conservation and Development D. A. SCOTT, Director DIVISION OF GEOLOGY S. SHEDD, Supe.rvisor BULLETIN No. 30 (Geological Series) The Mineral Resources of Washington WITH STATISTICS FOR 1922 BY SOLON SHEDD With an Article on Coal and Coke BY GEORGE WATKIN EVANS OLYMPlA FRANK lf. LAMBORN, PUBLIC PRI NTER 1924 DEPARTMENTAL ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT D. A. SCOT'!', Director Olympia. FRED W. AGATZ, Chief Assistant Director Olympia. DIVISION OF WATER RESOURCES MARVIN CHASE. Supet·msor Olympia. DIVISION OF RECLAMATION DIVISION OF COLUMBIA BASIN SURVEY DIVISION OF FORESTRY F . E. PAPE, Supermsor Olympia DIVISION OF GEOLOGY S. SBEDD, St1pervlsor Pullman LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Hon. D. A. Scott, Director, Department of Conse·rvation and Development, Olympia, Washington. Sm: I have the honor to submit herewith the manu script of a report on the Mineral Resources of Washing ton and recommend that it b~ published as a Bulletin of the Department of Conservation and Development and designated as Geological Series No. 30. Very respectfully, s. S HEDD, Swperviso·r, Division of Geology. College Station, Pulhpan, Washington. June 20, 1924. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page [ NTROOUOTJON • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • . • • • • • • • . • • • . • . • • . • • • • • . • • • • • • 11 Tabulation of Mineral Production of Washington, from 1915 to 1922, Inclusive . 13 PART I. METALLIC MINERALS. METALLIC MINERALS •. • . • . • • . • . • . • • . • . 17 Mining Conditions In Washington During 1923.... ......... 17 Gold .. 19 Silver .. 20 Copper . 20 Lead .. 21 Zinc .. 21 Metal Mines Now or Recently in Operation. 22 Tabulation or Metallic Production Totals... ..... .... ...... 23 Gold . 32 Ore Minerals . 32 Uses of Gold . 32 Gold in Washington . 33 Silver . 35 Ore Minerals . 35 Uses of Silver . -

Mark Hotel in Downtown St

Easter Sunrise Services - April 7 1996 - Washington, DC As we enter the spring season, it is always a great feeling that we celebrate Easter with services at the George Washington Masonic National Memorial in Alexandria, Virginia. What a beautiful setting for our services. If you have not been in attendance at one of the Easter Services you have missed a once-in-a-lifetime event that is available to a Knight Templar. One faces the east and sees in the distance the dome of our nations capitol and the skyline of monuments that spell out our great heritage as Masons and citizens of this great country of ours. This year the services will be under the supervision of our Grand Prelate, Sir Knight Donald Hinslea Smith, Past Grand Master of the Grand Encampment of Knights Templar of the United States of America. Whenever Sir Knight Don speaks, he always has a very interesting message and lesson for all of us. Sir Knight Richard Baldwin, Honorary Past Department Commander, Past Grand Commander of Virginia and General Chairman of the Committee on the Easter Sunrise Memorial Service, has a message for all attending in regard to the package deal with the Hotel Washington and also for those who wish to obtain Saturday luncheon tickets and Easter morning breakfast tickets. Remember, all presiding Grand Commanders and their ladies are guests of the Grand Encampment for the Saturday noonday luncheon. See page 13 of this issue for Sir Knight Baldwin's message. Membership Retention Right Worshipful Brother and Sir Knight George H. Hohenshildt, Past Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania, has called a meeting of the leaders of Freemasonry which include the Sovereign Grand Commanders of both jurisdictions of the Scottish Rite and the Grand Master of the Grand Encampment to see what can be done to retain members who already have or are drifting away from our Masonic organization through demits and suspensions for nonpayment of dues. -

Current Operationally Complete Projects

Operationally Complete Projects Connecting Washington, Nickel, and TPA Projects Operationally Complete in 2021 and 2020 This detailed report describes Connecting Washington, Nickel, and TPA projects that have been completed in the prior month. This monthly count of operationally complete projects may differ from quarterly Gray Notebook reporting because some projects are included here at the time they are completed, even though they may be part of a larger project that is yet to be completed. Project Title Revenue Package On time* Operationally Complete Date SR 167/I-5 to SR 509 - Stage 1A 2015 Connecting late 8/12/2021 (Pierce) 316708T Washington I-5/Steilacoom-DuPont Rd to Thorne Ln - 2015 Connecting late 8/1/2021 Corridor Improvements (Pierce) Washington 300503T I-5/SR 510 Interchange - Reconstruct 2015 Connecting late 7/17/2021 Interchange (Thurston) 300502C Washington I-90/Bullfrog Rd Vic to Cle Elum Vic - Nickle late 6/28/2021 Replace/Rehab Concrete (Kittitas) 509027T I-90/Medical Lake I/C to Geiger Field 2015 Connecting late 6/18/2021 I/C - Reconstruction (Spokane) Washington 609047C SR 99/Alaskan Way Viaduct Demolition Nickle and TPA late 6/13/2021 & Battery St Tunnel Decommissioning (King) 809939X SR 107/Chehalis River Bridge - 2015 Connecting late 5/24/2021 Structural Rehabilitation (Grays Harbor) Washington 310702B No Nickel, TPA, or Connecting Washington projects operationally complete in April 2021. No Nickel, TPA, or Connecting Washington projects operationally complete in March 2021. No Nickel, TPA, or Connecting Washington projects operationally complete in February 2021. SR 240/Duportail Rd Intersection 2015 Connecting 12/16/2020 Improvements (Benton) 524003W Washington No Nickel, TPA, or Connecting Washington projects operationally complete in November 2020. -

Evidence on Time-Of-Day Transit Pricing in the United States

203 Evidence on • A apartment of portation o4-4() Time-of-Day Pricing in the United States—, DEPARTMENT OF Volume 2: Appendices TRANSPORTATION and Case Studies NOV ^ 6 1984 LIBRARY May 1984 Evidence on Time-of-Day Pricing in the United States, Volume 2: Appendices and Case Studies May 1984 DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION nov a 6 190' LIBRARY Prepared by Robert Qervero, with research assistance ' from Mark Hansen, Therese Watkins, and Joel Markowitz Institute of Urban and Regional Development University of California Berkeley, California 94720 Prepared for Office of Management Research and Transit Services Urban Mass Transportation Administration U.S. Department of Transportation Washington, D.C. 20590 In cooperation with Technology Sharing Program Office of the Secretary of Transportation Washington, D.C. 20590 DOT-l-84-40 Forward This is the companion volume to the research report on Evidence on Time-of-Day Transit Pricing in the United States . This volume serves as an expanded appendix to the Volume 1 report, principally providing detailed case-by-case summaries on experiences with time-of-day transit pricing to date. It provides the interested reader with more in-depth background information on the reasons for adopting time-of-day pricing, the impacts recorded to date, implementation issues, a national survey of transit officials, along with a theoretical summary of the time-of- day pricing concept. Appendix I presents thirty-two individual case study summaries on time-of-day transit pricing experiences. Attention focuses on each rationale for adopting time-of-day pricing, trends and impacts associ- ated with the fare programs, and assorted implementation issues. -

Bulletin 37, Inventory of Washington Minerals Part II, Metallic, Volume 1

Selenium Occurrences 283 OCCURRENCES The map showing the numbered selenium occurrences Golden Valley is plate 18, on page 47 in volume 2. (see Valley under gold) Lamefoot FERRY COUNTY (see Valley under gold) Blaine Republic Republic (3) (see Republic under gold) ( see under gold) Flag Hill (2) Valley (1) ( see under gold) (see under gold) SILICON Properties-Although silicon is ordinarily classified as Production-In Washington ferrosilicon is produced in a nonmetallic element, it does possess some metallic prop electric furnaces at three plants, those of the Keokuk erties, and the pure element is commonly called "silicon Electro-Metals Co. at Rock Island, the Ohio Ferro-Alloys metal." Massive silicon is crystalline, lustrous, gray black, Co. at Tacoma, and the Pacific Northwest Alloys, Inc. at and metallic appearing. It is brittle and is harder than Mead. Of these, the first two have produced metallic glass. It is classified as a semi-conductor; that is, it has silicon also. only slight conductivity for electricity. Silicon has poor mechanical properties, thus it presents a challenge to Prices-Silicon of 97 percent purity sold at 20 cents metallurgists to adapt it to structural uses in order to per pound in 1951; in August 1952 the price dropped to utilize such desirable characteristics as light weight 18¥., cents, and was still at that figure 3 years later. One (lighter than aluminum), corrosion resistance, high melt pound of extremely pure silicon for electrical use was ing point, and ease of production. Silicon is almost inert imported in 1950, and the quoted value was $517 per chemically at low temperatures but is active when heated. -

Strategic Minerals Investigations 1941

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Bulletin 931 STRATEGIC MINERALS INVESTIGATIONS 1941 PART 1, A-J Short papers and preliminary reports by EUGENE CALLAGHAN, S. W. HOBBS, L. R. PAGE and others UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1943 r:^^1 HALL LIBRARy ftf) CONTENTS (The letters in parentheses preceding the titles are those used to designate the papers for separate publication] ' * Page (A) Tungsten resources of the Blue Wing district, Lemhl * County, Idaho, by Eugene Callaghan and D; M. Lemmon (published in June 1941)............................ 1 (B) Some quicksilver prospects in adjacent parts of Nev- "^ ada, California, and Oregon, by C. P. Ross (pub- ! lished in June 1941)................................ 23 (C) Tin deposit at Majuba Hill, Pershing County, Nevada, by W. C. Smith and V. P. Gianella (published in March 1942)......................................... 39 ^ (D) Nickel-gold deposit near Mount Vernon, Skagit County, Washington, by S. W. Hobbs and W. T. Pecora (pub lished in January 1942)............................. 57 (E) Tungsten deposits in the Sierra Nevada near Bishop, California, a preliminary report, by D. M. Lemmon (published in March 1942)........................... 79 (P) Nickel deposits of Bohemia Basin and vicinity, Yakobi > Island, Alaska, by J. C. Reed and J. V. N. Dorr 2d (published in May 1942)............................. 105 (G) Chroiaite deposits of Kenal Peninsula, Alaska, by P. W. ' Guild (published in March 1942)..................... 139 * (H) Tin and tungsten deposits at Silver Hill, Spokane County, Washington, by L. R. Page (published in Au- , gust 1942)........................................... 177 '' (I) Nickel deposit near Riddle, Douglas County, Oregon, by W. -

Bulletin 37, Inventory of Washington Minerals Part II, Metallic

108 Inventory of Washington Minerals-Part II, Metallic Minerals PEND OREILLE COUNTY Black Rock (3) (see under zinc) 0. K. (2) (see under silver) Farmer (4) (see under zinc) Pend Oreille Mines & Metals Co. (1) (see under zinc) Lucile (1) (see under zinc) New England (5) STEVENS COUNTY (see under zinc) Advance (2) Old Dominion (6) (see under zinc) ( see under silver) GERMANIUM Properties-Germanium is a rare metal allied to tin. Missouri, but small production was coming from at least It is grayish white, lustrous, crystalline, light in weight, two other plants in Pennsylvania and New York. Pro hard, and brittle. It is a semiconductor of electricity, a duction was at the rate of 1,000 pounds per year in 1948 property which is utilized in the manufacture of electronic but had increased to 6,000 pounds in 1951 and was expand devices. Germanium expands upon solidification. It amal ing rapidly. Germanium is recovered from flue dusts in gamates with mercury and is known to form alloys with England. Zinc concentrates from the Metaline district in aluminum, copper, silver, magnesium, and some other Washington are germaniferous, hence have been shipped metals. It is resistant to corrosion and is stable in air to Mississippi Valley smelters, where the germanium is at temperatures up to 600° C. It has valences of 2 and 4 recoverable in horizontal-retort smelters. and forms two corresponding series of compounds. Other Prices-Germanium metal was quoted in 1936 at $5.50 properties are shown in the table on page 12. per gram, and in 1940 at $4,500 per pound, but by 1946 Uses-Germanium had very few uses for many years, it had dropped to $180 per pound.