University of California, Berkeley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clifford-Ishi's Story

ISHI’S STORY From: James Clifford, Returns: Becoming Indigenous in the 21st Century. (Harvard University Press 2013, pp. 91-191) Pre-publication version. [Frontispiece: Drawing by L. Frank, used courtesy of the artist. A self-described “decolonizationist” L. Frank traces her ancestry to the Ajachmem/Tongva tribes of Southern California. She is active in organizations dedicated to the preservation and renewal of California’s indigenous cultures. Her paintings and drawings have been exhibited world wide and her coyote drawings from News from Native California are collected in Acorn Soup, published in 1998 by Heyday Press. Like coyote, L. Frank sometimes writes backwards.] 2 Chapter 4 Ishi’s Story "Ishi's Story" could mean “the story of Ishi,” recounted by a historian or some other authority who gathers together what is known with the goal of forming a coherent, definitive picture. No such perspective is available to us, however. The story is unfinished and proliferating. My title could also mean “Ishi's own story,” told by Ishi, or on his behalf, a narration giving access to his feelings, his experience, his judgments. But we have only suggestive fragments and enormous gaps: a silence that calls forth more versions, images, endings. “Ishi’s story,” tragic and redemptive, has been told and re-told, by different people with different stakes in the telling. These interpretations in changing times are the materials for my discussion. I. Terror and Healing On August 29th, 1911, a "wild man,” so the story goes, stumbled into civilization. He was cornered by dogs at a slaughterhouse on the outskirts of Oroville, a small town in Northern California. -

Ishi and Anthropological Indifference in the Last of His Tribe

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 3 No. 11; June 2013 "I Heard Your Singing": Ishi and Anthropological Indifference in the Last of His Tribe Jay Hansford C. Vest, Ph.D. Enrolled member Monacan Indian Nation Direct descendent Opechanchanough (Pamunkey) Honorary Pikuni (Blackfeet) in Ceremonial Adoption (June 1989) Professor of American Indian Studies University of North Carolina at Pembroke One University Drive (P. O. Box 1510) Pembroke, NC 28372-1510 USA. The moving and poignant story of Ishi, the last Yahi Indian, has manifested itself in the film drama The Last of His Tribe (HBO Pictures/Sundance Institute, 1992). Given the long history of Hollywood's misrepresentation of Native Americans, I propose to examine this cinematic drama attending historical, ideological and cultural axioms acknowledged in the film and concomitant literature. Particular attention is given to dramatic allegorical themes manifesting historical racism, Western societal conquest, and most profoundly anthropological indifference, as well as, the historical accuracy and the ideological differences of worldview -- Western vis-à-vis Yahi -- manifest in the film. In the study of worldviews and concomitant values, there has long existed a lurking "we" - "they" proposition of otherness. Ever since the days of Plato and his Western intellectual predecessors, there has been an attempt to locate and explicate wisdom in the ethnocentric ideological notion of the "civilized" vis-à-vis the "savage." Consequently, Plato's thoughts are accorded the standing of philosophy -- the love of wisdom -- while Black Elk's words are the musings of the "primitive" and consigned to anthropology -- the science of man. Philosophy is, thusly, seen as an endeavor of "civilized" Western man whom in his "science of man" or anthropological investigation may record the "ethnometaphysics" of "primitive" or "developing" cultures. -

Genocide and the Indians of California, 1769-1873 Margaret A

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Graduate Masters Theses Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses 5-1993 Genocide and the Indians of California, 1769-1873 Margaret A. Field University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses Part of the Native American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Field, Margaret A., "Genocide and the Indians of California, 1769-1873" (1993). Graduate Masters Theses. Paper 141. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENOCIDE AND THE INDIANS OF CALIFORNIA , 1769-1873 A Thesis Presented by MARGARET A. FIELD Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies and Research of the Un1versity of Massachusetts at Boston in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS MAY 1993 HISTCRY PROGRAM GENOCIDE AND THE I NDIAN S OF CALIFORNIA, 1769-187 3 A Thesis P resented by MARGARET A. FIELD Approved as to style and content by : Clive Foss , Professor Co - Chairperson of Committee mes M. O'Too le , Assistant Professor -Chairpers on o f Committee Memb e r Ma rshall S. Shatz, Pr og~am Director Department of History ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank professors Foss , O'Toole, and Buckley f or their assistance in preparing this manuscri pt and for their encouragement throughout the project . -

Ishi, the Last Wild Indian, 2001 Peabody Essex Museum David P

Ishi, the Last Wild Indian, 2001 Peabody Essex Museum David P. Bradley, White Earth Ojibwe (1954 - ) Salem in History, 2006 Ishi, the Last Wild Indian, 2001 David P. Bradley, White Earth Ojibwe (1954 - ) Santa Fe, N.M. Mixed Media on Board Gift of Mr. & Mrs. James N. Krebs, 2001 E301825 H I S T O R I C A L C O N T E X T Ishi (c.1860-1916) was the last living member of the Yahi tribe, the southernmost tribe of the Yana people who inhabited northern California and the Sacramento Valley.The California gold rush and influx of foreign- ers contributed to the quick demise of the Yana tribes through conflict and disease. Apparently the last surviving Yahi, Ishi journeyed into white society, and was brought to the Museum of Anthropology in San Francisco by anthropologist Alfred Lewis Kroeber. He worked as both a janitor and as a “living exhibit,” making arrowheads in front of paying museum visitors and helping researchers record the Yana language.This survivor did not divulge information about his deceased family, however, and he did not even reveal his own name. “Ishi” means “man” in Yana. The mysterious person known as Ishi did in 1916, a victim of tuberculosis, which was foreign to the Yahi. Rumors spread that Ishi’s brain had been preserved after his death, but it wasn’t until 1999 that his pickled brain was found in a Smithsonian museum warehouse.This prompted much controversy and political debate.The Smithsonian agreed to return Ishi’s brain to surviving Native American tribes closely related to the Yahi, and it was buried with Ishi’s body in 2000. -

High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California

High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California Suzanna Theresa Montague B.A., Colorado College, Colorado Springs, 1982 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ANTHROPOLOGY at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2010 High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California A Thesis by Suzanna Theresa Montague Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Mark E. Basgall, Ph.D. __________________________________, Second Reader David W. Zeanah, Ph.D. ____________________________ Date ii Student: Suzanna Theresa Montague I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, ___________________ Michael Delacorte, Ph.D, Graduate Coordinator Date Department of Anthropology iii Abstract of High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California by Suzanna Theresa Montague The study investigated pre-contact land use on the western slope of California’s central Sierra Nevada, within the subalpine and alpine zones of the Tuolumne River watershed, Yosemite National Park. Relying on existing data for 373 archaeological sites and minimal surface materials collected for this project, examination of site constituents and their presumed functions in light of geography and chronology indicated two distinctive archaeological patterns. First, limited-use sites—lithic scatters thought to represent hunting, travel, or obsidian procurement activities—were most prevalent in pre- 1500 B.P. contexts. Second, intensive-use sites, containing features and artifacts believed to represent a broader range of activities, were most prevalent in post-1500 B.P. -

Student Magazine Historic Photograph of Siletz Feather Dancers in Newport for the 4Th of July Celebration in the Early 1900S

STUDENT MAGAZINE Historic photograph of Siletz Feather dancers in Newport for the 4th of July celebration in the early 1900s. For more information, see page 11. (Photo courtesy of the CT of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw). The Oregon Historical Society thanks contributing tradition bearers and members of the Nine Federally Recognized Tribes for sharing their wisdom and preserving their traditional lifeways. Text by: Lisa J. Watt, Seneca Tribal Member Carol Spellman, Oregon Historical Society Allegra Gordon, intern Paul Rush, intern Juliane Schudek, intern Edited by: Eliza Canty-Jones Lisa J. Watt Marsha Matthews Tribal Consultants: Theresa Peck, Burns Paiute Tribe David Petrie, Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians Angella McCallister, Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community Deni Hockema, Coquille Tribe, Robert Kentta, Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians Susan Sheoships, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and Museum at Tamástslikt Cultural Institute Myra Johnson, Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation Louis La Chance, Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians Perry Chocktoot, The Klamath Tribes Photographs provided by: The Nine Federally Recognized Tribes Oregon Council for the Humanities, Cara Unger-Gutierrez and staff Oregon Historical Society Illustration use of the Plateau Seasonal Round provided by Lynn Kitagawa Graphic Design: Bryan Potter Design Cover art by Bryan Potter Produced by the Oregon Historical Society 1200 SW Park Avenue, Portland, OR 97205 Copyright -

The Return of Ishi's Brain: After an Unsettling Discovery, Anthropologists Reconsider a Legendary Friendship by Christopher Shea Lingua Franca February 2000

The Return of Ishi's Brain: After an Unsettling Discovery, Anthropologists Reconsider a Legendary Friendship By Christopher Shea Lingua Franca February 2000 IN CALIFORNIA, EVERY SCHOOLCHILD learns the story of Ishi, the last Yahi Indian. On August 29, 1911, he stumbled out of the woods in Oroville, California, 180 miles northeast of San Francisco, his hair singed black in a display of mourning. It was a shocking event: Native Americans, it was thought, had long since been driven onto reservations or onto the margins of white settlements. According to the best-known version of the Ishi story, barking dogs awakened workers at an Oroville slaughterhouse early in the morning. The butchers found a man cowering, near starvation, beside a corral leading into the building. They called the local sheriff, who handcuffed the Indian and brought him to the town jail for safekeeping. As word spread about Oroville's new resident, Northern Californians streamed into town to gawk at "the last wild Indian in North America." The Oroville officials contacted the University of California, which dispatched an anthropologist, T.T. Waterman, to the scene. He pronounced Ishi a "Stone Age man"—a sobriquet that stuck to him for life—and took him back to San Francisco by train. Waterman and his fellow anthropologists housed Ishi in a room in the university's museum and set about learning as much of his story as they could. He remained in the museum, working as a janitor and putting on the occasional flint- making show—sometimes for crowds of hundreds—until 1916, when he succumbed to tuberculosis. -

Phonetic Description of a Three-Way Stop Contrast in Northern Paiute

UC Berkeley Phonology Lab Annual Report (2010) Phonetic description of a three-way stop contrast in Northern Paiute Reiko Kataoka Abstract This paper presents the phonetic description of a three-way phonemic contrast in the medial stops (lenis, fortis, and voiced fortis stops) of a southern dialect of Northern Paiute. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of VOT, closure duration, and voice quality was performed on field recordings of a female speaker from the 1950s. The findings include that: 1) voiced fortis stops are realized phonetically as voiceless unaspirated stops; 2) the difference between fortis and voiced fortis and between voiced fortis and lenis in terms of VOT is subtle; 3) consonantal duration is a robust acoustic characteristic differentiating the three classes of stops; 4) lenis stops are characterized by a smooth VC transition, while fortis stops often exhibit aspiration at the VC juncture, and voiced fortis stops exhibit occasional glottalization at the VC juncture. These findings suggest that the three-way contrast is realized by combination of multiple phonetic properties, particularly the properties that occur at the vowel-consonant boundary rather than the consonantal release. 1. Introduction Northern Paiute (NP) belongs to the Western Numic branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family and is divided into two main dialect groups: the northern group, Oregon Northern Paiute, and the southern group, Nevada Northern Paiute (Nichols 1974:4). Some of the southern dialects of Nevada Northern Paiute, known as Southern Nevada Northern Paiute (SNNP) (Nichols 1974), have a unique three-way contrast in the medial obstruent: ‗fortis‘, ‗lenis‘, and what has been called by Numic specialists the ‗voiced fortis‘ series. -

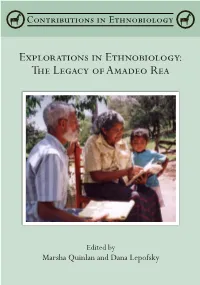

Explorations in Ethnobiology: the Legacy of Amadeo Rea

Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea Edited by Marsha Quinlan and Dana Lepofsky Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea Edited by Marsha Quinlan and Dana Lepofsky Copyright 2013 ISBN-10: 0988733013 ISBN-13: 978-0-9887330-1-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012956081 Society of Ethnobiology Department of Geography University of North Texas 1155 Union Circle #305279 Denton, TX 76203-5017 Cover photo: Amadeo Rea discussing bird taxonomy with Mountain Pima Griselda Coronado Galaviz of El Encinal, Sonora, Mexico, July 2001. Photograph by Dr. Robert L. Nagell, used with permission. Contents Preface to Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea . i Dana Lepofsky and Marsha Quinlan 1 . Diversity and its Destruction: Comments on the Chapters . .1 Amadeo M. Rea 2 . Amadeo M . Rea and Ethnobiology in Arizona: Biography of Influences and Early Contributions of a Pioneering Ethnobiologist . .11 R. Roy Johnson and Kenneth J. Kingsley 3 . Ten Principles of Ethnobiology: An Interview with Amadeo Rea . .44 Dana Lepofsky and Kevin Feeney 4 . What Shapes Cognition? Traditional Sciences and Modern International Science . .60 E.N. Anderson 5 . Pre-Columbian Agaves: Living Plants Linking an Ancient Past in Arizona . .101 Wendy C. Hodgson 6 . The Paleobiolinguistics of Domesticated Squash (Cucurbita spp .) . .132 Cecil H. Brown, Eike Luedeling, Søren Wichmann, and Patience Epps 7 . The Wild, the Domesticated, and the Coyote-Tainted: The Trickster and the Tricked in Hunter-Gatherer versus Farmer Folklore . .162 Gary Paul Nabhan 8 . “Dog” as Life-Form . .178 Eugene S. Hunn 9 . The Kasaga’yu: An Ethno-Ornithology of the Cattail-Eater Northern Paiute People of Western Nevada . -

Northern Paiute of California, Idaho, Nevada and Oregon

טקוּפה http://family.lametayel.co.il/%D7%9E%D7%A1%D7%9F+%D7%A4%D7%A8%D7%A0%D7 %A1%D7%99%D7%A1%D7%A7%D7%95+%D7%9C%D7%9C%D7%90%D7%A1+%D7%9 5%D7%92%D7%90%D7%A1 تاكوبا Τακόπα The self-sacrifice on the tree came to them from a white-bearded god who visited them 2,000 years ago. He is called different names by different tribes: Tah-comah, Kate-Zahi, Tacopa, Nana-bush, Naapi, Kul-kul, Deganaweda, Ee-see-cotl, Hurukan, Waicomah, and Itzamatul. Some of these names can be translated to: the Pale Prophet, the bearded god, the Healer, the Lord of Water and Wind, and so forth. http://www.spiritualjourneys.com/article/diary-entry-a-gift-from-an-indian-spirit/ Chief Tecopa - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chief_Tecopa Chief Tecopa From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Chief Tecopa (c.1815–1904) was a Native American leader, his name means wildcat. [1] Chief Tecopa was a leader of the Southern Nevada tribe of the Paiute in the Ash Meadows and Pahrump areas. In the 1840s Tecopa and his warriors engaged the expedition of Kit Carson and John C. Fremont in a three-day battle at Resting Springs.[2] Later on in life Tecopa tried to maintain peaceful relations with the white settlers to the region and was known as a peacemaker. [3] Tecopa usually wore a bright red band suit with gold braid and a silk top hat. Whenever these clothes wore out they were replaced by the local white miners out of gratitude for Tecopa's help in maintaining peaceful relations with the Paiute. -

Bibliographies of Northern and Central California Indians. Volume 3--General Bibliography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 370 605 IR 055 088 AUTHOR Brandt, Randal S.; Davis-Kimball, Jeannine TITLE Bibliographies of Northern and Central California Indians. Volume 3--General Bibliography. INSTITUTION California State Library, Sacramento.; California Univ., Berkeley. California Indian Library Collections. St'ONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. Office of Library Programs. REPORT NO ISBN-0-929722-78-7 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 251p.; For related documents, see ED 368 353-355 and IR 055 086-087. AVAILABLE FROMCalifornia State Library Foundation, 1225 8th Street, Suite 345, Sacramento, CA 95814 (softcover, ISBN-0-929722-79-5: $35 per volume, $95 for set of 3 volumes; hardcover, ISBN-0-929722-78-7: $140 for set of 3 volumes). PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian History; *American Indians; Annotated Bibliographies; Films; *Library Collections; Maps; Photographs; Public Libraries; *Resource Materials; State Libraries; State Programs IDENTIFIERS *California; Unpublished Materials ABSTRACT This document is the third of a three-volume set made up of bibliographic citations to published texts, unpublished manuscripts, photographs, sound recordings, motion pictures, and maps concerning Native American tribal groups that inhabit, or have traditionally inhabited, northern and central California. This volume comprises the general bibliography, which contains over 3,600 entries encompassing all materials in the tribal bibliographies which make up the first two volumes, materials not specific to any one tribal group, and supplemental materials concerning southern California native peoples. (MES) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** U.S. -

Lassen National Forest Backcountry Discovery Trail! Know Before You Go

Get Ready to Explore! Drive 187 miles of unparalleled beauty. Discover a geological playground. Hike to alpine snowfields. Relax at quiet lakes while raptors soar overhead. Trace the footsteps of Gold Rush emigrants. Discover the heritage of northern California. Welcome to the Lassen National Forest Backcountry Discovery Trail! Know Before You Go The Lassen Backcountry Discovery Trail was established to invite exploration of the remote areas of the Lassen backcountry. The Trail generally follows gravel and dirt roads and is intended for high clearance street- legal vehicles. Expect rough road conditions and slow travel through remote country. Be prepared for downed trees or rocks on the road. Much of the route is under snow in the winter Volcanic views and early spring. There are no restaurants, grocery stores, or gas stations along the main route and cell phone coverage is intermittent. Introduction ~ ~ Stay Current Off-road motor vehicle travel is prohibited in the Lassen National Forest; please stay on designated routes. Call any forest office for updated road condition and project work information that may affect your travel plans. Periodic updates to the Trail maps in this Guide may occur to reflect changes in vehicle use or other revisions. Map updates and other Lassen Backcountry Discovery Trail information may be found at: www.fs.fed.us/r5/lassen/ Your Planning Checklist Lassen National Forest Visitor Map Adequate food, water, and fuel Friends to share the fun, and assist in an emergency Insect repellant and first-aid kit Know how to identify poison oak Toilet paper and shovel to bury human waste GPS unit, binoculars, and camera Campfire permit if you plan to use a fire, barbecue, or camp stove (available for free at most Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, California Department of Forestry/Fire Protection offices or fire stations).