Beyond the Arena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lord Lyon King of Arms

VI. E FEUDAE BOBETH TH F O LS BABONAG F SCOTLANDO E . BY THOMAS INNES OP LEABNEY AND KINNAIRDY, F.S.A.ScoT., LORD LYON KIN ARMSF GO . Read October 27, 1945. The Baronage is an Order derived partly from the allodial system of territorial tribalis whicn mi patriarce hth h hel s countrydhi "under God", d partlan y froe latemth r feudal system—whic e shale wasw hse n li , Western Europe at any rate, itself a developed form of tribalism—in which the territory came to be held "of and under" the King (i.e. "head of the kindred") in an organised parental realm. The robes and insignia of the Baronage will be found to trace back to both these forms of tenure, which first require some examination from angle t usuallno s y co-ordinatedf i , the later insignia (not to add, the writer thinks, some of even the earlier understoode symbolsb o t e )ar . Feudalism has aptly been described as "the development, the extension organisatione th y sa y e Family",o familyth fma e oe th f on n r i upon,2o d an Scotlandrelationn i Land;e d th , an to fundamentall o s , tribaa y l country, wher e predominanth e t influences have consistently been Tribality and Inheritance,3 the feudal system was immensely popular, took root as a means of consolidating and preserving the earlier clannish institutions,4 e clan-systeth d an m itself was s modera , n historian recognisew no s t no , only closely intermingled with feudalism, but that clan-system was "feudal in the strictly historical sense".5 1 Stavanger Museums Aarshefle, 1016. -

Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory

Skidmore College Creative Matter MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 MALS 5-20-2006 Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory Liane Fisher Skidmore College Follow this and additional works at: https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol Part of the Dance Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Liane, "Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory" (2006). MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019. 41. https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol/41 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the MALS at Creative Matter. It has been accepted for inclusion in MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 by an authorized administrator of Creative Matter. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Thesis Skidmore College Liane Fisher March 2006 Advisor: Isabel Brown Reader: Marc Andre Wiesmann Table of Contents Abstract .............................. ... .... .......................................... .......... ............................ ...................... 1 Chapter 1 : Introduction .. .................................................... ........... ..... ............ ..... ......... ............. 2 My thologyand Ballet ... ....... ... ........... ................... ....... ................... ....... ...... .................. 7 The Labyrinth My thologies .. ......................... .... ................. .......................................... -

Gestural Ekphrasis: Toward a Phenomenology of the Moving Body in Joyce and Woolf

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2018 Gestural Ekphrasis: Toward a Phenomenology of the Moving Body in Joyce and Woolf Lauren Nicole Benke University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Benke, Lauren Nicole, "Gestural Ekphrasis: Toward a Phenomenology of the Moving Body in Joyce and Woolf" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1401. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1401 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Gestural Ekphrasis: Toward a Phenomenology of the Moving Body in Joyce and Woolf __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Lauren N. Benke March 2018 Advisor: Eleanor McNees © Lauren N. Benke 2018 All Rights Reserved Author: Lauren N. Benke Title: Gestural Ekphrasis: Toward a Phenomenology of the Moving Body in Joyce and Woolf Advisor: Eleanor McNees Degree Date: March 2018 ABSTRACT This theoretical project seeks to introduce a new critical methodology for evaluating gesture—both represented in text and paratextual—in the works of Virginia Woolf—specifically The Voyage Out (1915), Orlando (1928), The Waves (1931), and Between the Acts (1941)—and James Joyce—particularly Ulysses (1922) and Finnegans Wake (1939). -

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad An extract from the Irish Sport Horse Studbook Stallion Book The Irish Sport Horse Studbook is maintained by Horse Sport Ireland and the Northern Ireland Horse Board Horse Sport Ireland First Floor, Beech House, Millennium Park, Osberstown, Naas, Co. Kildare, Ireland Telephone: 045 850800. Int: +353 45 850800 Fax: 045 850850. Int: +353 45 850850 Email: [email protected] Website: www.horsesportireland.ie Northern Ireland Horse Board Office Suite, Meadows Equestrian Centre Embankment Road, Lurgan Co. Armagh, BT66 6NE, Northern Ireland Telephone: 028 38 343355 Fax: 028 38 325332 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nihorseboard.org Copyright © Horse Sport Ireland 2015 HIGH PERFORMANCE STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD INDEX OF APPROVED STALLIONS BY BREED HIGH PERFORMANCE RECOGNISED FOREIGN BREED STALLIONS & STALLIONS STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD & ACANTUS GK....................................4 APPROVED THROUGH AI ACTION BREAKER.............................4 BALLOON [GBR] .............................10 KROONGRAAF............................... 62 AIR JORDAN Z.................................. 5 CANABIS Z......................................18 LAGON DE L'ABBAYE..................... 63 ALLIGATOR FONTAINE..................... 6 CANTURO.......................................19 LANDJUWEEL ST. HUBERT ............ 64 AMARETTO DARCO ......................... 7 CASALL LA SILLA.............................22 LARINO.......................................... 66 -

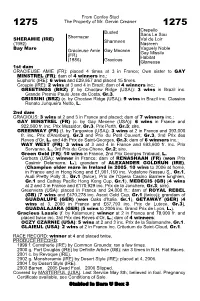

From Confey Stud the Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner Busted

From Confey Stud 1275 The Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner 1275 Crepello Busted Sans Le Sou Shernazar Val de Loir SHERAMIE (IRE) Sharmeen (1992) Nasreen Bay Mare Vaguely Noble Gracieuse Amie Gay Mecene Gay Missile (FR) Habitat (1986) Gracious Glaneuse 1st dam GRACIEUSE AMIE (FR): placed 4 times at 3 in France; Own sister to GAY MINSTREL (FR); dam of 4 winners inc.: Euphoric (IRE): 6 wins and £29,957 and placed 15 times. Groupie (IRE): 2 wins at 3 and 4 in Brazil; dam of 4 winners inc.: GREETINGS (BRZ) (f. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 3 wins in Brazil inc. Grande Premio Paulo Jose da Costa, Gr.3. GRISSINI (BRZ) (c. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 9 wins in Brazil inc. Classico Renato Junqueira Netto, L. 2nd dam GRACIOUS: 3 wins at 2 and 3 in France and placed; dam of 7 winners inc.: GAY MINSTREL (FR) (c. by Gay Mecene (USA)): 6 wins in France and 922,500 fr. inc. Prix Messidor, Gr.3, Prix Perth, Gr.3; sire. GREENWAY (FR) (f. by Targowice (USA)): 3 wins at 2 in France and 393,000 fr. inc. Prix d'Arenberg, Gr.3 and Prix du Petit Couvert, Gr.3, 2nd Prix des Reves d'Or, L. and 4th Prix de Saint-Georges, Gr.3; dam of 6 winners inc.: WAY WEST (FR): 3 wins at 3 and 4 in France and 693,600 fr. inc. Prix Servanne, L., 3rd Prix du Gros-Chene, Gr.2; sire. Green Gold (FR): 10 wins in France, 2nd Prix Georges Trabaud, L. Gerbera (USA): winner in France; dam of RENASHAAN (FR) (won Prix Casimir Delamarre, L.); grandam of ALEXANDER GOLDRUN (IRE), (Champion older mare in Ireland in 2005, 10 wins to 2006 at home, in France and in Hong Kong and £1,901,150 inc. -

The Grave Goods of Roman Hierapolis

THE GRAVE GOODS OF ROMAN HIERAPOLIS AN ANALYSIS OF THE FINDS FROM FOUR MULTIPLE BURIAL TOMBS Hallvard Indgjerd Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History University of Oslo This thesis is submitted for the degree of Master of Arts June 2014 The Grave Goods of Roman Hierapolis ABSTRACT The Hellenistic and Roman city of Hierapolis in Phrygia, South-Western Asia Minor, boasts one of the largest necropoleis known from the Roman world. While the grave monuments have seen long-lasting interest, few funerary contexts have been subject to excavation and publication. The present study analyses the artefact finds from four tombs, investigating the context of grave gifts and funerary practices with focus on the Roman imperial period. It considers to what extent the finds influence and reflect varying identities of Hierapolitan individuals over time. Combined, the tombs use cover more than 1500 years, paralleling the life-span of the city itself. Although the material is far too small to give a conclusive view of funerary assem- blages in Hierapolis, the attempted close study and contextual integration of the objects does yield some results with implications for further studies of funerary contexts on the site and in the wider region. The use of standard grave goods items, such as unguentaria, lamps and coins, is found to peak in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. Clay unguentaria were used alongside glass ones more than a century longer than what is usually seen outside of Asia Minor, and this period saw the development of new forms, partially resembling Hellenistic types. Some burials did not include any grave gifts, and none were extraordinarily rich, pointing towards a standardised, minimalistic set of funerary objects. -

Gladiator Politics from Cicero to the White House

Gladiator Politics from Cicero to the White House The gladiator has become a popular icon. He is the hero fighting against the forces of oppression, a Spartacus or a Maximus. He is the "gridiron gladiator" of Monday night football. But he is also the politician on the campaign trail. The casting of the modern politician as gladiator both appropriates and transforms ancient Roman attitudes about gladiators. Ancient gladiators had a certain celebrity, but they were generally identified as infames and antithetical to the behavior and values of Roman citizens. Gladiatorial associations were cast as slurs against one's political opponents. For example, Cicero repeatedly identifies his nemesis P. Clodius Pulcher as a gladiator and accuses him of using gladiators to compel political support in the forum by means of violence and bloodshed in the Pro Sestio. In the 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns the identification of candidates as gladiators reflects a greater complexity of the gladiator as a modern cultural symbol than is reflected by popular film portrayals and sports references. Obama and Clinton were compared positively to "two gladiators who have been at it, both admired for sticking at it" in their "spectacle" of a debate on February 26, 2008 by Tom Ashbrook and Mike McIntyre on NPR's On Point. Romney and Gingrich appeared on the cover of the February 6, 2012 issue of Newsweek as gladiators engaged in combat, Gingrich preparing to stab Romney in the back. These and other examples of political gladiators serve, when compared to texts such as Cicero's Pro Sestio, as a means to examine an ancient cultural phenomenon and modern, popularizing appropriations of that phenomenon. -

Accidents, Racing 191, 193, 194–5, 197 Aedile 2–3, 12–13, 17–18

248 INDEX Index accidents, racing 191, 193, 194–5, 197 Anthology, Planudian 198, 201–2 aedile 2–3, 12–13, 17–18 Antiochus IV Epiphanes 10–11, 118, Aemilius Lepidus, M. 3, 6, 121, 223 223, 232 n.14 Aemilius Paullus, L. 8, 9–11, 223, Antoninus Pius, Emperor 132 232–3 n.23 Antony, Mark 28–9, 60, 129–30, 224 Ahenobarbus, Gn. Domitius 208 Aphrodisias 149–50 Alypius 188 Apollonius 118–19 Ammianus Marcellinus 204, 214 Appian 28, 77, 126, 127, 128, 129, Amphitheater, Flavian (Colosseum) 61, 218 62–6, 79–80, 82, 113–15, 154, 221, Apuleius 104 225, 235 n.18 aquacade 220–1 amphitheaters 29, 47, 52, 61–2, 66–7, armatures, gladiatorial 223, 224, 235 n.8, 235 n.12 dimachaerus 85 military 52, 66–7 eques 97, 99, 100, 101–2, 103, 150 permanent structures 56–7, 60–1 essedarius 85, 96, 97, 100, 121, 144, podium barrier 59, 67, 107 150, 152: essedaria 103, 187 special effects 65–6, 69 Gallus 95, 121 temporary 57–9, 61–2, 110 hoplomachus 85, 96, 97, 100 Androclus 93–4 murmillo 85, 95, 96, 97, 98, 100, 101, animal hunt see venatio 150, 151, 237 n.14 animals 56, 59, 66, 70, 89, 91, 104, retiarius 95, 96, 97, 98, 100, 101, 116–17, 124, 183, 197, 198, 221 142, 145, 146, 152, 182, 237 n.14, bears 35, 44, 56, 89, 90, 92, 93, 104, 238 n.15 116 Samnite 21, 95, 96, 121, 140, 155 cats, large 4, 17–18, 21, 35, 47–8, secutor 95, 98–9, 145 49–51, 56, 67, 89, 90, 93–4, 114, Thraex 85, 95, 96, 97, 100, 103, 105, 115, 116, 168, 173 121, 133, 146, 147, 151, 238 n.14 crocodiles 78–9 Artemidorus 147 elephants 7–8, 27, 35, 70, 113, 114, Asiaticus 131–2 116, 222 Athenaeus 10–11 hippopotamus 34, 89, 116 Athenagoras 167 rhinoceros 34, 115 Athens 118–19 Anthology, Greek 202 Attilius, M. -

Der Uebergang Der Römerstrasse Vindonissa- Bodensee Über Die Limmat Bei Baden

Der Uebergang der Römerstrasse Vindonissa- Bodensee über die Limmat bei Baden Autor(en): Matter, A. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Badener Neujahrsblätter Band (Jahr): 14 (1938) PDF erstellt am: 05.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-321215 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Der Uebergang der Römerstrasse Vindonissa-Bodensee über die Limmat bei Baden Von A. MATTER, Ingenieur Die Kenntnis des römischen Strassennetzes in der Schweiz gründet sich teils auf schriftliche Quellen, teils auf direkte Feststellungen durch Ausgrabungen und Bodenfunde. Als schriftliche Quellen kommen in der Hauptsache das Itinerarium Antonini und die Peutinger'sche Tafel in Frage; von geringerer Bedeutung sind Berichte der römischen Schriftsteller, welche in der Regel nur ganz allgemeine und vielfach ungenaue Angaben überliefern. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Liste Des Publications (Liste Chronologique)

Liste des publications (liste chronologique) ARTICLES 1969 1. «Die inoffiziellen Kaisertitulaturen im 1. und 2.Jh.n.Chr.», Museum Helveticum 26, 1969, 18-39. 1974 2. « Colonia Iulia Equestris (Staatsrechtliche Betrachtungen zum Gründungsdatum) » , Historia 23, 1974, 439-462. 1975 3. « Bemerkungen zum Helvetierfoedus», Schweiz.Zeitschrift für Geschichte 25, 1975, 127-141. 1976 4. « Die Schweiz in römischer Zeit: Der Vorgang der Provinzialisierung in rechtshistorischer Sicht», Historia 25, 1976, 313-355. 5. « Vicani Vindonissenses», Jahresbericht der Gesellschaft Pro Vindonissa 1976, 7- 22. 6. « Die römische Schweiz: Ausgewählte staats-und verwaltungsrechtliche Probleme im Frühprinzipat», ANRW II, 5, 1 (1976), 288-403. 1979 7. « Legio X Equestris», Talanta X/XI, 1978/79, 44 -61. 1980 8. « Zur Ziegelinschrift von Erlach», Archéologie suisse, 3, 1980, 103-105. 1981 9. « Die römischen Steininschriften aus Zurzach», Revue suisse d’histoire, 31, 1981, 43-59. 1982 10. Traduction allemande de la contribution de PIERRE DUCREY, « Vorzeit, Kelten, Römer (bis 401 n.Chr.) », in: Geschichte der Schweiz und der Schweizer, Basel ,1982, Band I, 19-104 11. « Zur Polizei in der Schweiz zur römischen Zeit», Nachrichtenblatt der Kantonspolizei Zürich 3, 1982, 42-44. 1983 12. « Die Erkennungsmarke (tessera hospitalis) aus Fundi imRätischen Museum, 1.Teil» Jahresbericht 1983 des Rätischen Museums Chur, 197-220. 1984 13. Alltag und Fest in Athen, Einführung in die Ausstellung Historisches Museum Bern, 27.Okt.1984- 6.Jan.1985 (traduction allemande de "La cité des images"), 17 p. 14. « Die Räter in den antiken Quellen», in: Das Räterproblem in geschichtlicher, sprachlicher und archäologischer Sicht, Schriftenreihe des Rätischen Museums Chur 28, 1984, 6-21. 15. -

The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476)

Impact of Empire 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd i 5-4-2007 8:35:52 Impact of Empire Editorial Board of the series Impact of Empire (= Management Team of the Network Impact of Empire) Lukas de Blois, Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin, Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt, Elio Lo Cascio, Michael Peachin John Rich, and Christian Witschel Executive Secretariat of the Series and the Network Lukas de Blois, Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn and John Rich Radboud University of Nijmegen, Erasmusplein 1, P.O. Box 9103, 6500 HD Nijmegen, The Netherlands E-mail addresses: [email protected] and [email protected] Academic Board of the International Network Impact of Empire geza alföldy – stéphane benoist – anthony birley christer bruun – john drinkwater – werner eck – peter funke andrea giardina – johannes hahn – fik meijer – onno van nijf marie-thérèse raepsaet-charlier – john richardson bert van der spek – richard talbert – willem zwalve VOLUME 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd ii 5-4-2007 8:35:52 The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476) Economic, Social, Political, Religious and Cultural Aspects Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, 200 B.C. – A.D. 476) Capri, March 29 – April 2, 2005 Edited by Lukas de Blois & Elio Lo Cascio With the Aid of Olivier Hekster & Gerda de Kleijn LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.