Lord Lyon King of Arms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lady Howard De Walden and the First World War

Lady Howard de Walden and the First World War Margherita van Raalte married the 8th Baron Howard de Walden in 1912 at St Marylebone Parish Church where Lord Howard de Walden was Crown Warden. At the time the name was over 300 years old, granted to Lord Howard by Elizabeth I in 1588, supposedly in gratitude for his bravery in battle against the Spanish Armada. Margherita possessed the aristocrat’s structure – her neck was long, and took its languid time to meet her body. Her fingers were slim and graceful: designed to dangle jewels or to barely hold a fan of feathers. And her eyebrows rushed downwards: the titled lady’s suffering, hooded glory.After holding the ancient name for only a few years, she too was fighting. She defied the Director General of Army Services who refused to give her permission to take on a Matron and eleven private nurses and establish a convalescent hospital in Egypt. It became the Convalescent Hospital No. 6, in Alexandria. A newspaper article from January 10, 1916 read: “A visit was paid to Lady Howard de Walden’s British Red Cross hospital which was formerly a palatial residence. Much marble has been used in its construction, and it stands amidst beautiful grounds. Among the patients were 36 New Zealanders. Lady de Walden’s husband, who is serving with the Forces in the Dardanelles, is one of the richest men in England, and both husband and wife have been generous and indefatigable to a degree. New Zealanders who come to this hospital are indeed fortunate.” This patient is wearing his ‘hospital blues’. -

The Heraldry Ofspatx and Portugal

^ 49 THE HERALDRY OF SPATX AND PORTUGAL. By the Rev. JOHN WOODWARD, F.S.A,, Scot. ^lore than half a century has elapsed since Mr. Ford commenced in the pages of the ' Quarterly Review,' tlie publication of his interesting papers on Spanish matters. In them the art, the literature, the architec- ture, and the amusements of tlie great Peninsular kingdom were passed in relating.'^ review, and made the subjects of most valuable papers ; which, to a country, slower to change than almost any in Europe, and, moreover, lying somewhat out of the beaten track of ordinary travel, are still a storehouse of information on Cosas de Espana which no one who visits Spain, or writes on its affairs, would be wise to overlook. Among those papers is one published in 1838, upon " Spanish Genealogy and Heraldry,"- whicli is so full of interesting matter that many of the readers of tue Genealogist may be thankful to be informed or reminded of its existence, although fifty years have passed since its publication. The paper is one, moreover, which is of interest as being * one of tlie very few to whicli the editors of the Quarterly Review ' have permitted the introduction of illustrative woodcuts. These are, indeed, only seven in number, and they are not particularly well chosen, or well executed ; the reader will find remarks on some of them before the close of this paper. It is the purpose of the present writer to deal only with the second- named of the subjects of ]\Ir. Ford's article, and to leave its curious information with regard to Spanish Genealogies for treatment on some future occasion. -

A History of the Lairds of Grant and Earls of Seafield

t5^ %• THE RULERS OF STRATHSPEY GAROWNE, COUNTESS OF SEAFIELD. THE RULERS OF STRATHSPEY A HISTORY OF THE LAIRDS OF GRANT AND EARLS OF SEAFIELD BY THE EARL OF CASSILLIS " seasamh gu damgean" Fnbemess THB NORTHERN COUNTIES NEWSPAPER AND PRINTING AND PUBLISHING COMPANY, LIMITED 1911 M csm nil TO CAROLINE, COUNTESS OF SEAFIELD, WHO HAS SO LONG AND SO ABLY RULED STRATHSPEY, AND WHO HAS SYMPATHISED SO MUCH IN THE PRODUCTION OP THIS HISTORY, THIS BOOK IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR. PREFACE The material for " The Rulers of Strathspey" was originally collected by the Author for the article on Ogilvie-Grant, Earl of Seafield, in The Scots Peerage, edited by Sir James Balfour Paul, Lord Lyon King of Arms. A great deal of the information collected had to be omitted OAving to lack of space. It was thought desirable to publish it in book form, especially as the need of a Genealogical History of the Clan Grant had long been felt. It is true that a most valuable work, " The Chiefs of Grant," by Sir William Fraser, LL.D., was privately printed in 1883, on too large a scale, however, to be readily accessible. The impression, moreover, was limited to 150 copies. This book is therefore published at a moderate price, so that it may be within reach of all the members of the Clan Grant, and of all who are interested in the records of a race which has left its mark on Scottish history and the history of the Highlands. The Chiefs of the Clan, the Lairds of Grant, who succeeded to the Earldom of Seafield and to the extensive lands of the Ogilvies, Earls of Findlater and Seafield, form the main subject of this work. -

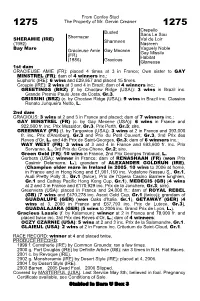

From Confey Stud the Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner Busted

From Confey Stud 1275 The Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner 1275 Crepello Busted Sans Le Sou Shernazar Val de Loir SHERAMIE (IRE) Sharmeen (1992) Nasreen Bay Mare Vaguely Noble Gracieuse Amie Gay Mecene Gay Missile (FR) Habitat (1986) Gracious Glaneuse 1st dam GRACIEUSE AMIE (FR): placed 4 times at 3 in France; Own sister to GAY MINSTREL (FR); dam of 4 winners inc.: Euphoric (IRE): 6 wins and £29,957 and placed 15 times. Groupie (IRE): 2 wins at 3 and 4 in Brazil; dam of 4 winners inc.: GREETINGS (BRZ) (f. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 3 wins in Brazil inc. Grande Premio Paulo Jose da Costa, Gr.3. GRISSINI (BRZ) (c. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 9 wins in Brazil inc. Classico Renato Junqueira Netto, L. 2nd dam GRACIOUS: 3 wins at 2 and 3 in France and placed; dam of 7 winners inc.: GAY MINSTREL (FR) (c. by Gay Mecene (USA)): 6 wins in France and 922,500 fr. inc. Prix Messidor, Gr.3, Prix Perth, Gr.3; sire. GREENWAY (FR) (f. by Targowice (USA)): 3 wins at 2 in France and 393,000 fr. inc. Prix d'Arenberg, Gr.3 and Prix du Petit Couvert, Gr.3, 2nd Prix des Reves d'Or, L. and 4th Prix de Saint-Georges, Gr.3; dam of 6 winners inc.: WAY WEST (FR): 3 wins at 3 and 4 in France and 693,600 fr. inc. Prix Servanne, L., 3rd Prix du Gros-Chene, Gr.2; sire. Green Gold (FR): 10 wins in France, 2nd Prix Georges Trabaud, L. Gerbera (USA): winner in France; dam of RENASHAAN (FR) (won Prix Casimir Delamarre, L.); grandam of ALEXANDER GOLDRUN (IRE), (Champion older mare in Ireland in 2005, 10 wins to 2006 at home, in France and in Hong Kong and £1,901,150 inc. -

THE FAMILY of SKENE. Her First Husband), In1438

I EOBEET DE SKENE, Baron of=Marion Mercer, daughter of the Skene. King Eobeet Bbuce gave Baron of Aldie and Meiklure, "a charter to him, stillpreserved, Perthshire. dilecto et fidelinostro Roberto Skene," erecting his lands into a Barony, 1317. Tradition asserts he was 10th or 12th Laird of Skene, and that the old Tower of Skene was the firstbuilt stone house inMar.^Douglas' Baronage" describes him as grandson of John de Skene, a man of eminent rank and dis- tinction, who swore allegiance to Edwabd 1., 1296," and who was, says Nisbet, "an arbiter between Bruce and Baliol, 1290." GILIAN DE SKENE, Baron of= Skene. | ADAM DE SKENE, Jiaron of- Skene. | ADAM DE SKENE, Baron of= Skene. | ADAM DE SKENE, killed at=Janet Keith, daughter of the the battle of Harlaw, 1411. [ Great Marischal of Scotland. JAMES DE SKENE, 1411-1461,=" The Widow of Fraser, of Corn- designated, in1446, as nobilis toun. The Exchequer Rolls virJacobus de Skene de eodem." show that from 1428 to 1435, ¦v He m. 2nd Egidia or Giles de James L of Scotland paid Moravia, of Culbin, in Moray- annually £6 13s. 4d. to James shire, widow of Thomas de Skene of Skene, for his occupa- Kinnaird, of that Ilk,and grand- tionof terce lands of Comtoun, daughter and heiress of Gilbert belonging to Skene's Wife, widow Moray, of Culbin and Skelbo, by of a Fraser of Comtoun. Eustach, daughter of Kenneth, 3rd Earl of Sutherland. 19rwent ALEXANDERDE SKENE, 1461-= Marietta de Kinnaird, daughter of 1470, who continued the contest Thos. de Kinnaird, by Egidia de ( with the Earl Marischal family Moravia. -

The London Gazette, 3 March, 1925. 1525

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 3 MARCH, 1925. 1525 War Office, Henry Key, Walter Bull, Thomas Howard %?th February, 1925. Deighton, Thomas Robinson, Robert Peachey, Henry Martin Gaydon, Thomas Pimm, Sidney The KING has been pleased to issue a New John Sandle, Horace Davies Singer, Joseph Commission of Lieutenancy for the City of James Redding, George Josiah Berridge, Har- London, bearing date November 8th, 1924, vey Edward Preen, Sir Richard Davies, constituting and appointing the several Knight, Commander of Our Most Excellent persons undermentioned to be His Majesty's Order of the British Empire, Thomas Goldney, Lieutenants within the said City, as Harold Elliott Sparks, George Thomas Sirrell follows:— Tranter and Samuel Alderton, Esquires, To OUR right trusty and well-beloved Colonel Deputies of Our City of London and the Depu- Sir Louis Arthur Arthur Newton, Baronet, ties of Our said City for the time being; OUR Lord Mayor of Our City of London, and the trusty and well-beloved Francis Howse, Lord Mayor of Our said City for the time Esquire, Lieutenant - Colonel Sir John being; OUR right trusty and well-beloved Humphery, Knight, Sir George Alexander Marcus, Lord Bearsted of Maidstone, OUR Touche, Sir John Lulham Pound, Baronets, trusty and well-beloved Sir George Wyatt Thomas Andrew Blane, Esquire, Colonel Sir Truscott, Sir John Knill, Colonel Sir David William Henry Dunn, Baronet, George Burnett, Colonel Sir Thomas Vansittart Briggs, Harry John Newman, Esquires, for- Bowater, Colonel Sir Charles Johnston, merly Aldermen of Our City of London; -

Lady Wisdom and Dame Folly at Qumran

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department Classics and Religious Studies September 1998 LADY WISDOM AND DAME FOLLY AT QUMRAN Sidnie White Crawford University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub Part of the Classics Commons Crawford, Sidnie White, "LADY WISDOM AND DAME FOLLY AT QUMRAN" (1998). Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department. 23. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. LADY WISDOM AND DAME FOLLY AT QUMRAN SIDNIE WHITE CRAWFORD University of Nebraska-Lincoln* The female fi gures of Lady Wisdom and Dame Folly, found in the post- exilic Wisdom literature, have always attracted much debate and specula- tion. The questions of who they are and what they stand for, particularly in the case of Lady Wisdom, have been hotly debated. Is she merely a liter- ary creation, driven by the fact that the nouns for wisdom in Hebrew and and σοφία, are feminine in gender? Or is she an actual divine חכמה ,Greek fi gure, a female hypostasis of Yahweh, the god of Israel, indicating a fe- male divine presence in Israelite religion? These debates have yet to be re- solved. Now that the large corpus of sapiential texts from Qumran is begin- ning to be studied, new light may be shed on the fi gures of Lady Wisdom and Dame Folly. -

Battrum's Guide and Directory to Helensburgh and Neighbourhood

ii t^^ =»». fl,\l)\ National Library of Scotland ^6000261860' Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/battrumsguidedir1875batt u : MACNEUR & BRYDEN'S (31.-A.TE ""w. :b.aji}t:rtji^'&] GUIDE AND DIRECTORY TO HELENSBURGH AND NEIGHBOURHOOD, SEVENTH EDITIOK. ;^<A0MSjdi^ HELENSBUEGH MACNEUE & BUT & 52 East Princes Street, aad 19 West Clyde Street, 1875. 7. PREFACE. In issning the seventh edition of the Helensburgh Direc- tory, the publishers, remembering the kind apprecia- tion it received when published by the late Mr Battrum, trust that it will meet with a similar reception. Although imperfect in many respects, considerabie care has been expended in its compiling. It is now larger than anj^ previous issue, and the publishers doubt not it will be found useful as a book of reference in this daily increasing district. The map this year has been improved, showing the new feus, houses, and streets that have been made ; and, altogether, every effort has been made to render tbe Directory worthy of the town and neighbourhood. September' 1875. NAMES OF THE NEW POLICE COMMISSIONERS, Steveu, Mag. Wilhaiii Bryson. Thomas Chief j J. W. M'Culloch, Jun. Mag. John Crauib. John Stuart, Jun. Mag. Donald Murray. Einlay Campbell. John Dingwall, Alexander Breingan. B. S. MFarlane. Andrew Provan. Martin M' Kay. Towii-CJerk—Geo, Maclachlan. Treasurer—K. D, Orr. Macneur & Bkyden (successors to the late W. Battrum), House Factors and Accountants. House Register published as formerly. CONTENTS OF GUIDE. HELENSBURGH— page ITS ORIGIN, ..,.,..., 9 OLD RECORDS, H PROVOSTS, 14 CHURCHES, 22 BANKS, 26 TOWN HALL, . -

The Education and Training of Gentry Sons in Early Modern England

Working Papers No. 128/09 The Education and Training of Gentry Sons in Early-Modern England . Patrick Wallis & Cliff Webb © Patrick Wallis, LSE Cliff Webb, Independent Scholar November 2009 Department of Economic History London School of Economics Houghton Street London, WC2A 2AE Tel: +44 (0) 20 7955 7860 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7955 7730 The Education and Training of Gentry Sons in Early-Modern England* Patrick Wallis and Cliff Webb Abstract: This paper explores the education and training received by the sons of the English gentry in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Using information from the herald’s visitations of four counties, it offers quantitative evidence of the proportion of gentry children who entered university, spent time at one of the inns of court or became apprentices in London. We show that over the period there was little change in the educational destinations of gentry sons: university and apprenticeship absorbed roughly equal proportions; the inns of court slightly less. We also show that a son’s position in the birth order had a very strong influence on the kind of education he received. Eldest sons were much more likely to go to university or one of the inns of court. Younger sons were much more likely to become apprentices in London – as we show, trade clearly was an acceptable career for the gentry. There is little sign of a change in the status of different educational choices in this period. Our findings confirm some traditional assumptions about the importance of birth order and normative expectations in determining the life-courses of gentry children in the seventeenth century: historians should not over-state the autonomy of elite children in deciding their futures. -

Golnaz Nanbakhsh University of Edinburgh Politeness and Address Forms in Contemporary Persian: Thirty Years On

Golnaz Nanbakhsh University of Edinburgh Politeness and address forms in contemporary Persian: Thirty years on Abstract. This paper examines the correlation between language use (particularly address terms and pronouns), politeness norms, and social structure in contemporary Iranian society. The Persian system of address terms in post-revolutionary Iran was influenced by the Islamic ideology of the early 1979 Iranian revolution (Keshavarz 1988). These terms include extensive use of kinship terms such as bæradær ‘brother’ and xahær ‘sister’ in public domains, which clearly illustrate that influence. In an attempt to investigate the impact of the 1979 revolution on language use and politeness, the patterns of contemporary Persian address usage are compared with the social and political structure of the 1979 egalitarian ethos. Ten hours of spontaneous media conversation (candid camera and interviews) and 20 sociolinguistics interviews gathered in Iran are analysed. The interactional analysis reveals variation within the Persian address system leading to changes in linguistic and social structuring of language in contemporary Iran. Keywords: Address terms, politeness, variation, social and cultural revolution, Persian. Acknowledgments I would like to express my profound appreciation to Prof. Miriam Meyerhoff, and Dr. Graeme Trousdale, my PhD supervisors at the University of Edinburgh, for their persistent and insightful comments on the thesis on which this article is based. Whatever infelicities remain are of course my own responsibility. 1. Introduction Macro- and micro-sociolinguistic research indicates variations and changes in the address systems of many languages, including those with a T ‘informal you’ (French Tu) and V ‘formal you’ (French Vous) distinction (Brown and Gilman 1960). -

Farwell to Feudalism

Burke's Landed Gentry - The Kingdom in Scotland This pdf was generated from www.burkespeerage.com/articles/scotland/page14e.aspx FAREWELL TO FEUDALISM By David Sellar, Honorary Fellow, Faculty of Law, University of Edinburgh "The feudal system of land tenure, that is to say the entire system whereby land is held by a vassal on perpetual tenure from a superior is, on the appointed day, abolished". So runs the Sixth Act to be passed in the first term of the reconvened Scottish Parliament, The Abolition of Feudal Tenure etc (Scotland) Act 2000. The Act is welcome. By the end of the second millennium the feudal system had long outlived its usefulness, even as a legal construct, and had few, if any defenders. As the Scottish Law Commission commented in 1999, "The main reason for recommending the abolition of the feudal system of land tenure is that it has degenerated from a living system of land tenure with both good and bad features into some-thing which, in the case of many but not all superiors, is little more than an instrument for extracting money". The demise of feudalism brings to an end a story which began almost a thousand years ago, and which has involved all of Scotland's leading families. In England the advent of feudalism is often associated with the Norman Conquest of 1066. That Conquest certainly marked a new beginning in landownership which paved the way for the distinctive Anglo-Norman variety of feudalism. There was a sudden and virtually clean sweep of the major landowners. By the date of the Domesday Survey in 1086, only two major landowners of pre-Conquest vintage were left south of the River Tees holding their land direct of the crown: Thurkell of Arden (from whom the Arden family descend), and Colswein of Lincoln. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 164 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, JULY 12, 2018 No. 117 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was In April 2010, members of the Penn- fices in McKean County and Harris- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- sylvania Oil and Gas Association and burg. The association employs an pore (Mr. DESJARLAIS). the Independent Oil and Gas Associa- eight-person staff, and each year, f tion of Pennsylvania, IOGA, unani- PIOGA hosts several conferences, semi- mously voted to merge the two organi- nars, public educational meetings, DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO zations into a single, comprehensive presentations, and community events TEMPORE trade association representing oil and at a variety of locations across the The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- natural gas interests throughout Penn- Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. fore the House the following commu- sylvania. Mr. Speaker, I wish PIOGA the best nication from the Speaker: The merger reunited two organiza- as it gathers in Titusville to celebrate WASHINGTON, DC, tions that had split apart nearly some 100 years of growth and sustainability July 12, 2018. 30 years earlier to form the Pennsyl- in the Pennsylvania oil and gas indus- I hereby appoint the Honorable SCOTT vania Independent Oil and Gas Associa- try. The industry has a rich history in DESJARLAIS to act as Speaker pro tempore tion, or PIOGA. the Commonwealth, and I know that, on this day. A century later, industry leaders, as PIOGA looks forward to the future, PAUL D.