Following Sub-Sections: 1) Languageintroduction, Grade 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of the CHMP Meeting 14-17 September 2020

13 January 2021 EMA/CHMP/625456/2020 Corr.1 Human Medicines Division Committee for medicinal products for human use (CHMP) Minutes for the meeting on 14-17 September 2020 Chair: Harald Enzmann – Vice-Chair: Bruno Sepodes Disclaimers Some of the information contained in these minutes is considered commercially confidential or sensitive and therefore not disclosed. With regard to intended therapeutic indications or procedure scopes listed against products, it must be noted that these may not reflect the full wording proposed by applicants and may also vary during the course of the review. Additional details on some of these procedures will be published in the CHMP meeting highlights once the procedures are finalised and start of referrals will also be available. Of note, these minutes are a working document primarily designed for CHMP members and the work the Committee undertakes. Note on access to documents Some documents mentioned in the minutes cannot be released at present following a request for access to documents within the framework of Regulation (EC) No 1049/2001 as they are subject to on- going procedures for which a final decision has not yet been adopted. They will become public when adopted or considered public according to the principles stated in the Agency policy on access to documents (EMA/127362/2006). 1 Addition of the list of participants Official address Domenico Scarlattilaan 6 ● 1083 HS Amsterdam ● The Netherlands Address for visits and deliveries Refer to www.ema.europa.eu/how-to-find-us Send us a question Go to www.ema.europa.eu/contact Telephone +31 (0)88 781 6000 An agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency, 2020. -

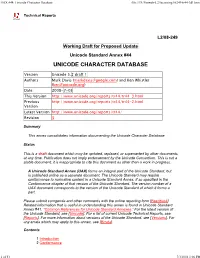

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database File:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-Tr44-3D1.Html

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database file:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-tr44-3d1.html Technical Reports L2/08-249 Working Draft for Proposed Update Unicode Standard Annex #44 UNICODE CHARACTER DATABASE Version Unicode 5.2 draft 1 Authors Mark Davis ([email protected]) and Ken Whistler ([email protected]) Date 2008-7-03 This Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-3.html Previous http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-2.html Version Latest Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/ Revision 3 Summary This annex consolidates information documenting the Unicode Character Database. Status This is a draft document which may be updated, replaced, or superseded by other documents at any time. Publication does not imply endorsement by the Unicode Consortium. This is not a stable document; it is inappropriate to cite this document as other than a work in progress. A Unicode Standard Annex (UAX) forms an integral part of the Unicode Standard, but is published online as a separate document. The Unicode Standard may require conformance to normative content in a Unicode Standard Annex, if so specified in the Conformance chapter of that version of the Unicode Standard. The version number of a UAX document corresponds to the version of the Unicode Standard of which it forms a part. Please submit corrigenda and other comments with the online reporting form [Feedback]. Related information that is useful in understanding this annex is found in Unicode Standard Annex #41, “Common References for Unicode Standard Annexes.” For the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see [Unicode]. For a list of current Unicode Technical Reports, see [Reports]. -

Martin Van Buren: the Greatest American President

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Martin Van Buren The Greatest American President —————— ✦ —————— JEFFREY ROGERS HUMMEL resident Martin Van Buren does not usually receive high marks from histori- ans. Born of humble Dutch ancestry in December 1782 in the small, upstate PNew York village of Kinderhook, Van Buren gained admittance to the bar in 1803 without benefit of higher education. Building on a successful country legal practice, he became one of the Empire State’s most influential and prominent politi- cians while the state was surging ahead as the country’s wealthiest and most populous. -

Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory

Skidmore College Creative Matter MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 MALS 5-20-2006 Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory Liane Fisher Skidmore College Follow this and additional works at: https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol Part of the Dance Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Liane, "Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory" (2006). MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019. 41. https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol/41 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the MALS at Creative Matter. It has been accepted for inclusion in MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 by an authorized administrator of Creative Matter. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mythological Intertextuality in Nineteenth Century Ballet Repertory Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Thesis Skidmore College Liane Fisher March 2006 Advisor: Isabel Brown Reader: Marc Andre Wiesmann Table of Contents Abstract .............................. ... .... .......................................... .......... ............................ ...................... 1 Chapter 1 : Introduction .. .................................................... ........... ..... ............ ..... ......... ............. 2 My thologyand Ballet ... ....... ... ........... ................... ....... ................... ....... ...... .................. 7 The Labyrinth My thologies .. ......................... .... ................. .......................................... -

INDEX to Series of Interviews with Vice Admiral

INDEX to Series of Interviews with Vice Admiral Lawson P. Ramage U. S. Navy (Retired) VADM Ramage USS ADMIRAL CALLAHAN: gas turbine roll on/roll off ship, p 515; p 536. AGNEW, Dr. Harold M.: p 278-9. AIGUILLETTES: the wearing of by an aide, p 500-501. ALASKA TUG AND BARGE CO: a model contract with MSTS, p 533-4; Lou Johnson is the moving light, p 533-6. AMPHIBIOUS FORCE: Adm. Frank G. Fahrion takes command with idea of effecting a rejuvenation, p 252-3; Ramage asks for duty, p 252; gets command of the RANKIN, p 253-4; comments on the Amphibious Force, p 263-5. ANDERSON, Admiral George: p 335; P 339. ARCTIC OCEAN: see entry under Commander, SS Div. 52; reason for Navy's interest after WW II, p 204-5. ARMED FORCES STAFF COLLEGE: p 217-8; p 224-5. A/S WARFARE: The NOBSKA project, p 276 ff; the challenge of the nuclear SS, p 277; the new emphasis on oceanographic research, p 284-5. AWARDS: see entry under Admiral Lockwood: Submarine service awards contrasted with attitude in Destroyer service. P 198. BALDWIN, The Hon. Robert: Under Secretary of the Navy - calls Ramage back to Washington (March, 1967) to relieve Admiral Donaho as head of MSTS, p 510; p 560. USS BANG - SS: member of a wolf pack with PARCHE, p 126; her attack on a Japanese convoy, p 129; p 132. - 1 - VADM Ramage BAY OF PIGS: p 405-7. BENTLEY, Mrs. Helen: p 544. BESHANY, Vice Admiral Philip: p 349. USS BONEFISH - SS: lost through enemy action during operation BARNEY in the Sea of Japan, p 190. -

Gestural Ekphrasis: Toward a Phenomenology of the Moving Body in Joyce and Woolf

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2018 Gestural Ekphrasis: Toward a Phenomenology of the Moving Body in Joyce and Woolf Lauren Nicole Benke University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Benke, Lauren Nicole, "Gestural Ekphrasis: Toward a Phenomenology of the Moving Body in Joyce and Woolf" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1401. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1401 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Gestural Ekphrasis: Toward a Phenomenology of the Moving Body in Joyce and Woolf __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Lauren N. Benke March 2018 Advisor: Eleanor McNees © Lauren N. Benke 2018 All Rights Reserved Author: Lauren N. Benke Title: Gestural Ekphrasis: Toward a Phenomenology of the Moving Body in Joyce and Woolf Advisor: Eleanor McNees Degree Date: March 2018 ABSTRACT This theoretical project seeks to introduce a new critical methodology for evaluating gesture—both represented in text and paratextual—in the works of Virginia Woolf—specifically The Voyage Out (1915), Orlando (1928), The Waves (1931), and Between the Acts (1941)—and James Joyce—particularly Ulysses (1922) and Finnegans Wake (1939). -

Introduction Ronald Reagan’S Defining Vision for the 1980S— - and America

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction Ronald Reagan’s Defining Vision for the 1980s— -_and America There are no easy answers, but there are simple answers. We must have the courage to do what we know is morally right. ronald reagan, “the speech,” 1964 Your first point, however, about making them love you, not just believe you, believe me—I agree with that. ronald reagan, october 16, 1979 One day in 1924, a thirteen-year-old boy joined his parents and older brother for a leisurely Sunday drive roaming the lush Illinois country- side. Trying on eyeglasses his mother had misplaced in the backseat, he discovered that he had lived life thus far in a “haze” filled with “colored blobs that became distinct” when he approached them. Recalling the “miracle” of corrected vision, he would write: “I suddenly saw a glori- ous, sharply outlined world jump into focus and shouted with delight.” Six decades later, as president of the United States of America, that extremely nearsighted boy had become a contact lens–wearing, fa- mously farsighted leader. On June 12, 1987, standing 4,476 miles away from his boyhood hometown of Dixon, Illinois, speaking to the world from the Berlin Wall’s Brandenburg Gate, Ronald Wilson Reagan em- braced the “one great and inescapable conclusion” that seemed to emerge after forty years of Communist domination of Eastern Eu- rope. “Freedom leads to prosperity,” Reagan declared in his signature For general queries, contact [email protected] © Copyright, Princeton University Press. -

Reagan's Victory

Reagan’s ictory How HeV Built His Winning Coalition By Robert G. Morrison Foreword by William J. Bennett Reagan’s Victory: How He Built His Winning Coalition By Robert G. Morrison 1 FOREWORD By William J. Bennett Ronald Reagan always called me on my birthday. Even after he had left the White House, he continued to call me on my birthday. He called all his Cabinet members and close asso- ciates on their birthdays. I’ve never known another man in public life who did that. I could tell that Alzheimer’s had laid its firm grip on his mind when those calls stopped coming. The President would have agreed with the sign borne by hundreds of pro-life marchers each January 22nd: “Doesn’t Everyone Deserve a Birth Day?” Reagan’s pro-life convic- tions were an integral part of who he was. All of us who served him knew that. Many of my colleagues in the Reagan administration were pro-choice. Reagan never treat- ed any of his team with less than full respect and full loyalty for that. But as for the Reagan administration, it was a pro-life administration. I was the second choice of Reagan’s to head the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). It was my first appointment in a Republican administration. I was a Democrat. Reagan had chosen me after a well-known Southern historian and literary critic hurt his candidacy by criticizing Abraham Lincoln. My appointment became controversial within the Reagan ranks because the Gipper was highly popular in the South, where residual animosities toward Lincoln could still be found. -

A New Research Resource for Optical Recognition of Embossed and Hand-Punched Hindi Devanagari Braille Characters: Bharati Braille Bank

I.J. Image, Graphics and Signal Processing, 2015, 6, 19-28 Published Online May 2015 in MECS (http://www.mecs-press.org/) DOI: 10.5815/ijigsp.2015.06.03 A New Research Resource for Optical Recognition of Embossed and Hand-Punched Hindi Devanagari Braille Characters: Bharati Braille Bank Shreekanth.T Research Scholar, JSS Research Foundation, Mysore, India. Email: [email protected] V.Udayashankara Professor, Department of IT, SJCE, Mysore, India. Email: [email protected] Abstract—To develop a Braille recognition system, it is required to have the stored images of Braille sheets. This I. INTRODUCTION paper describes a method and also the challenges of Braille is a language for the blind to read and write building the corpora for Hindi Devanagari Braille. A few through the sense of touch. Braille is formatted to a Braille databases and commercial software's are standard size by Frenchman Louis Braille in 1825.Braille obtainable for English and Arabic Braille languages, but is a system of raised dots arranged in cells. Any none for Indian Braille which is popularly known as Bharathi Braille. However, the size and scope of the combination of one to six dots may be raised within each English and Arabic Braille language databases are cell and the number and position of the raised dots within a cell convey to the reader the letter, word, number, or limited. Researchers frequently develop and self-evaluate symbol the cell exemplifies. There are 64 possible their algorithm based on the same private data set and combinations of raised dots within a single cell. -

The Current State of Braille on Packaging in Canada and Whether It Should Change

Ryerson University Graphic Communications Management GCM 490 - 011: Thesis The Current State of Braille on Packaging in Canada and Whether it Should Change Prepared by: Betty Lim 500714268 7 December 2020 1 Abstract This paper aims to explore the current state of braille on packaging. It provides a brief history and overview on braille and braille on packaging that highlights key milestones. It offers facts and statistics on braille and visually impaired people. It also demonstrates the guidelines and how to properly execute braille on the packaging. The paper compares both sides of the topic to come to a final conclusion as to whether braille on packaging should be more commonplace in Canada. The advantages of implementing braille on packaging is that it is more inclusive, increases accessibility, convenience and independence for the visually impaired people. The disadvantages of implementing braille on packaging is that it is costly, it statistically benefits few, it is hard to implement and more importantly check. Other alternatives such as devices and emerging technologies are also examined as other means of providing the same solution that increased braille on packaging would. The paper evaluates the topic from three different perspectives: the everyday consumer, the manufacturer and the visually impaired to determine whether braille on packaging should be more commonplace in Canada. 2 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................. 2 Introduction .......................................................................................... -

Read an Excerpt

The Artist Alive: Explorations in Music, Art & Theology, by Christopher Pramuk (Winona, MN: Anselm Academic, 2019). Copyright © 2019 by Christopher Pramuk. All rights reserved. www.anselmacademic.org. Introduction Seeds of Awareness This book is inspired by an undergraduate course called “Music, Art, and Theology,” one of the most popular classes I teach and probably the course I’ve most enjoyed teaching. The reasons for this may be as straightforward as they are worthy of lament. In an era when study of the arts has become a practical afterthought, a “luxury” squeezed out of tight education budgets and shrinking liberal arts curricula, people intuitively yearn for spaces where they can explore together the landscape of the human heart opened up by music and, more generally, the arts. All kinds of people are attracted to the arts, but I have found that young adults especially, seeking something deeper and more worthy of their questions than what they find in highly quantitative and STEM-oriented curricula, are drawn into the horizon of the ineffable where the arts take us. Across some twenty-five years in the classroom, over and over again it has been my experience that young people of diverse religious, racial, and economic backgrounds, when given the opportunity, are eager to plumb the wellsprings of spirit where art commingles with the divine-human drama of faith. From my childhood to the present day, my own spirituality1 or way of being in the world has been profoundly shaped by music, not least its capacity to carry me beyond myself and into communion with the mysterious, transcendent dimension of reality. -

History of the Education of the Blind

HISTORY OF THE EDUCATION OF THE BLIND HISTORY OF THE EDUCATION OF THE BLIND BY W. H. ILLINGWORTH, F.G.T.B. SUPERINTENDENT OP HENSHAW's BLIND ASYLUM, OLD TRAFFORD, MANCHESTER HONORARY SECRETARY TO THE BOARD OF EXAMINERS OF THE COLLEGE OF TEACHERS OF THE BLIND LONDON SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON & COMPANY, LTD. 1910 PRISTKD BY HAZELL, WATSON AND VINEY, LI)., LONDON AND AYLKSBURY. MY BELOVED FRIEND AND COUNSELLOR HENRY J. WILSON (SECRETARY OP THE GARDNER'S TRUST FOR THE BLIND) THIS LITTLE BOOK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED IN THE EARNEST HOPE THAT IT MAY BE THE HUMBLE INSTRUMENT IN GOD'S HANDS OF ACCOMPLISHING SOME LITTLE ADVANCEMENT IN THE GREAT WORK OF THE EDUCATION OF THE BLIND W. II. ILLINGWORTH AUTHOR 214648 PREFACE No up-to-date treatise on the important and interesting " " subject of The History of the Education of the Blind being in existence in this country, and the lack of such a text-book specially designed for the teachers in our blind schools being grievously felt, I have, in response to repeated requests, taken in hand the compilation of such a book from all sources at my command, adding at the same time sundry notes and comments of my own, which the experience of a quarter of a century in blind work has led me to think may be of service to those who desire to approach and carry on their work as teachers of the blind as well equipped with information specially suited to their requirements as circumstances will permit. It is but due to the juvenile blind in our schools that the men and women to whom their education is entrusted should not only be acquainted with the mechanical means of teaching through the tactile sense, but that they should also be so steeped in blind lore that it becomes second nature to them to think of and see things from the blind person's point of view.