Reagan's Victory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRANSCRIPT: U.S. SECRET SERVICECOMMAND POST RADIO TRAFFIC from MARCH 30, 1981 the Following Is a Transcript of the Command Post

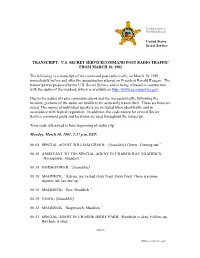

U.S Department of Homeland Security United States Secret Service TRANSCRIPT: U.S. SECRET SERVICECOMMAND POST RADIO TRAFFIC FROM MARCH 30, 1981 The following is a transcript of the command post radio traffic on March 30, 1981, immediately before and after the assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan. The transcript was prepared by the U.S. Secret Service and is being released in conjunction with the audio of the incident, which is available on http://www.secretservice.gov. Due to the nature of radio communications and the increased traffic following the incident, portions of the audio are unable to be accurately transcribed. These sections are noted. The names of individual speakers are included when identifiable and in accordance with federal regulation. In addition, the code names for several Secret Service command posts and locations are used throughout the transcript. Time code referenced is from beginning of audio clip. Monday, March 30, 1981, 2:27 p.m. EST: 00:08 SPECIAL AGENT WILLIAM GREEN: “[Inaudible] Green. Coming out.” 00:16 ASSISTANT TO THE SPECIAL AGENT IN CHARGE RAY SHADDICK: “Horsepower, Shaddick.” 00:18 HORSEPOWER: “[inaudible]” 00:19 SHADDICK: “Advise, we’ve had shots fired. Shots fired. There are some injuries, uh, lay one on.” 00:26 SHADDICK: “Parr, Shaddick.” 00:29 VOICE: [Inaudible] 00:32 SHADDICK: “Stagecoach, Shaddick.” 00:35 SPECIAL AGENT IN CHARGE JERRY PARR: “Rawhide is okay, Follow-up. Rawhide is okay.” -more- www.secretservice.gov -2- 00:40 VOICE: [Inaudible] [OVERLAPPING} 00:41 SHADDICK: “Halfback, roger” 00:46 SHADDICK: “You wanna go to the hospital or back to the White House?” 00:50 PARR: “We’re going right… we’re going to Crown.” 00:52 SHADDICK: “Okay” 00:56 VOICE: [Inaudible] 00:58 SHADDICK: “Back to the White House. -

WAR for the PLANET of the APES Written by Mark Bomback & Matt Reeves

WAR FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES Written by Mark Bomback & Matt Reeves Based on Characters Created by Rick Jaffa & Amanda Silver TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FINAL SHOOTING SCRIPT 10201 W. Pico Blvd. NOVEMBER 30, 2015 Los Angeles, CA 90064 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COPYRIGHT ©2015 TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM CORPORATION. NO PORTION OF THIS SCRIPT MAY BE PERFORMED, PUBLISHED, REPRODUCED, SOLD OR DISTRIBUTED BY ANY MEANS, OR QUOTED OR PUBLISHED IN ANY MEDIUM, INCLUDING ANY WEB SITE, WITHOUT THE PRIOR WRITTEN CONSENT OF TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM CORPORATION. DISPOSAL OF THIS SCRIPT COPY DOES NOT ALTER ANY OF THE RESTRICTIONS SET FORTH ABOVE. 1. BLACK SCREEN PRIMITIVE WAR DRUMS POUND OMINOUSLY... as a LEGEND BEGINS: Fifteen years ago, a scientific experiment gone wrong gave RISE to a species of intelligent apes… and destroyed most of humanity with a virus that became known as the Simian Flu. The word “RISE” lingers, moving toward us as it FADES... With the DAWN of a new ape civilization led by Caesar, the surviving humans struggled to coexist... but fighting finally broke out when a rebel ape, Koba, led a vengeful attack against the humans. The word “DAWN” lingers, moving toward us as it FADES... The humans sent a distress call to a military base in the North where all that remained of the U.S. Army was gathered. A ruthless Special Forces Colonel and his hardened battalion were dispatched to exterminate the apes. Evading capture for the last two years, Caesar is now rumored to be marshaling the fight from a hidden command base in the woods.. -

Mar Customer Order Form

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18MAR 2013 MAR COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Mar Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 3:35:28 PM Available only STAR WARS: “BOBA FETT CHEST from your local HOLE” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! MACHINE MAN THE WALKING DEAD: ADVENTURE TIME: CHARCOAL T-SHIRT “KEEP CALM AND CALL “ZOMBIE TIME” Preorder now! MICHONNE” BLACK T-SHIRT BLACK HOODIE Preorder now! Preorder now! 3 March 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 2/7/2013 10:05:45 AM X #1 kiNG CoNaN: Dark Horse ComiCs HoUr oF THe DraGoN #1 Dark Horse ComiCs GreeN Team #1 DC ComiCs THe moVemeNT #1 DoomsDaY.1 #1 DC ComiCs iDW PUBlisHiNG THe BoUNCe #1 imaGe ComiCs TeN GraND #1 UlTimaTe ComiCs imaGe ComiCs sPiDer-maN #23 marVel ComiCs Mar13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 2:21:38 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 2 #1 l ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT Uber #1 l AVATAR PRESS Suicide Risk #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Clive Barker’s New Genesis #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Marble Season HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Black Bat #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 1 Battlestar Galactica #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Grimm #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Wars In Toyland HC l ONI PRESS INC. The From Hell Companion SC l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Valiant Masters: Shadowman Volume 1: The Spirits Within HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Rurouni Kenshin Restoration Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Soul Eater Soul Art l YEN PRESS BOOKS & MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who: Who-Ology Official Miscellany HC l DOCTOR WHO / TORCHWOOD Doctor Who: The Official -

Drawn&Quarterly

DRAWN & QUARTERLY spring 2012 catalogue EXCERPT FROM GUY DELISLE’S JERUSALEM EXCERPT FROM GUY DELISLE’S JERUSALEM EXCERPT FROM GUY DELISLE’S JERUSALEM CANADIAN AUTHOR GUY DELISLE JERUSALEM Chronicles from the Holy City Acclaimed graphic memoirist Guy Delisle returns with his strongest work yet, a thoughtful and moving travelogue about life in Israel. Delisle and his family spent a year in East Jerusalem as part of his wife’s work with the non-governmental organiza- tion Doctors Without Borders. They were there for the short but brutal Gaza War, a three-week-long military strike that resulted in more than 1000 Palestinian deaths. In his interactions with the emergency medical team sent in by Doctors Without Borders, Delisle eloquently plumbs the depths of the conflict. Some of the most moving moments in Jerusalem are the in- teractions between Delisle and Palestinian art students as they explain the motivations for their work. Interspersed with these simply told, affecting stories of suffering, Delisle deftly and often drolly recounts the quotidian: crossing checkpoints, going ko- sher for Passover, and befriending other stay-at-home dads with NGO-employed wives. Jerusalem evinces Delisle’s renewed fascination with architec- ture and landscape as political and apolitical, with studies of highways, villages, and olive groves recurring alongside depictions of the newly erected West Bank Barrier and illegal Israeli settlements. His drawn line is both sensitive and fair, assuming nothing and drawing everything. Jerusalem showcases once more Delisle’s mastery of the travelogue. “[Delisle’s books are] some of the most effective and fully realized travel writing out there.” – NPR ALSO AVAILABLE: SHENZHEN 978-1-77046-079-9 • $14.95 USD/CDN BURMA CHRONICLES 978-1770460256 • $16.95 USD/CDN PYONGYANG 978-1897299210 • $14.95 USD/CDN GUY DELISLE spent a decade working in animation in Europe and Asia. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 111 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 111 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 156 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2010 No. 153 House of Representatives The House met at 2 p.m. and was PALLONE) come forward and lead the tives, the Clerk received the following mes- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- House in the Pledge of Allegiance. sage from the Secretary of the Senate on No- pore (Ms. RICHARDSON). Mr. PALLONE led the Pledge of Alle- vember 22, 2010 at 2:53 p.m.: giance as follows: That the Senate passed with amendments f H.R. 4783. DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the That the Senate concurs in House amend- United States of America, and to the Repub- PRO TEMPORE ment to Senate amendment H.R. 5566. lic for which it stands, one nation under God, That the Senate concurs in House amend- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. ments S. 3689. fore the House the following commu- f That the Senate passed S. 3650. nication from the Speaker: That the Senate passed with amendment COMMUNICATION FROM THE WASHINGTON, DC, H.R. 6198. November 29, 2010. CLERK OF THE HOUSE That the Senate agreed to without amend- I hereby appoint the Honorable LAURA The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- ment H. Con. Res. 327. RICHARDSON to act as Speaker pro tempore fore the House the following commu- With best wishes, I am on this day. -

English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada

Drawing on the Margins of History: English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada by Kevin Ziegler A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Kevin Ziegler 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This study analyzes the techniques that Canadian comics life writers develop to construct personal histories. I examine a broad selection of texts including graphic autobiography, biography, memoir, and diary in order to argue that writers and readers can, through these graphic narratives, engage with an eclectic and eccentric understanding of Canadian historical subjects. Contemporary Canadian comics are important for Canadian literature and life writing because they acknowledge the importance of contemporary urban and marginal subcultures and function as representations of people who occasionally experience economic scarcity. I focus on stories of “ordinary” people because their stories have often been excluded from accounts of Canadian public life and cultural history. Following the example of Barbara Godard, Heather Murray, and Roxanne Rimstead, I re- evaluate Canadian literatures by considering the importance of marginal literary products. Canadian comics authors rarely construct narratives about representative figures standing in place of and speaking for a broad community; instead, they create what Murray calls “history with a human face . the face of the daily, the ordinary” (“Literary History as Microhistory” 411). -

Introduction Ronald Reagan’S Defining Vision for the 1980S— - and America

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction Ronald Reagan’s Defining Vision for the 1980s— -_and America There are no easy answers, but there are simple answers. We must have the courage to do what we know is morally right. ronald reagan, “the speech,” 1964 Your first point, however, about making them love you, not just believe you, believe me—I agree with that. ronald reagan, october 16, 1979 One day in 1924, a thirteen-year-old boy joined his parents and older brother for a leisurely Sunday drive roaming the lush Illinois country- side. Trying on eyeglasses his mother had misplaced in the backseat, he discovered that he had lived life thus far in a “haze” filled with “colored blobs that became distinct” when he approached them. Recalling the “miracle” of corrected vision, he would write: “I suddenly saw a glori- ous, sharply outlined world jump into focus and shouted with delight.” Six decades later, as president of the United States of America, that extremely nearsighted boy had become a contact lens–wearing, fa- mously farsighted leader. On June 12, 1987, standing 4,476 miles away from his boyhood hometown of Dixon, Illinois, speaking to the world from the Berlin Wall’s Brandenburg Gate, Ronald Wilson Reagan em- braced the “one great and inescapable conclusion” that seemed to emerge after forty years of Communist domination of Eastern Eu- rope. “Freedom leads to prosperity,” Reagan declared in his signature For general queries, contact [email protected] © Copyright, Princeton University Press. -

Brady, James S.: Files

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Brady, James S.: Files Folder Title: [Press Conferences and Press Releases – Assassination Attempt] (3 of 3) Box: OA 16783 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing THE WHITE HOUSE Office of the Press Secretary March 31, 1981 NOTICE TO THE PRESS At 6:15 this morning, the President left. the recovery room for the intensive care ward. Dr. Daniel Ruge, the President's personal physician, said, "The President's vital signs are all in the normal range. He's in exceptionally good condition." Dr. Ruge indicated that the President was talking and writing notes. On James Brady's condition, Dr. Ruge said, "It is serious, but improving. It's too early to make a prognosis. He is somewhat responsive." Dr. Ruge also said that Secret Service agent Time.thy McCarthy's condition is "very fine." Doctors at the Washington Hospital Center said the condition of D.C. policeman Thomas Delahanty is serious, but the prognosis is good. At 5:30 this morning, Michael Reagan, Maureen Reagan, and Patti Davis arrived. at the White House. Ron Reagan and his wife, Doria, arrived last night. All of the children will be staying at the White House.· ##t THE WHITE HOUSE Off ice of the Press Secretary MARCH 31, 1981 NOTICE TO THE PRESS Dr. -

The Walking Dead,” Which Starts Its Final We Are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant Season Sunday on AMC

Las Cruces Transportation August 20 - 26, 2021 YOUR RIDE. YOUR WAY. Las Cruces Shuttle – Taxi Charter – Courier Veteran Owned and Operated Since 1985. Jeffrey Dean Morgan Call us to make is among the stars of a reservation today! “The Walking Dead,” which starts its final We are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant season Sunday on AMC. Call us at 800-288-1784 or for more details 2 x 5.5” ad visit www.lascrucesshuttle.com PHARMACY Providing local, full-service pharmacy needs for all types of facilities. • Assisted Living • Hospice • Long-term care • DD Waiver • Skilled Nursing and more Life for ‘The Walking Dead’ is Call us today! 575-288-1412 Ask your provider if they utilize the many benefits of XR Innovations, such as: Blister or multi-dose packaging, OTC’s & FREE Delivery. almost up as Season 11 starts Learn more about what we do at www.rxinnovationslc.net2 x 4” ad 2 Your Bulletin TV & Entertainment pullout section August 20 - 26, 2021 What’s Available NOW On “Movie: We Broke Up” “Movie: The Virtuoso” “Movie: Vacation Friends” “Movie: Four Good Days” From director Jeff Rosenberg (“Hacks,” Anson Mount (“Hell on Wheels”) heads a From director Clay Tarver (“Silicon Glenn Close reunited with her “Albert “Relative Obscurity”) comes this 2021 talented cast in this 2021 actioner that casts Valley”) comes this comedy movie about Nobbs” director Rodrigo Garcia for this comedy about Lori and Doug (Aya Cash, him as a professional assassin who grapples a straight-laced couple who let loose on a 2020 drama that casts her as Deb, a mother “You’re the Worst,” and William Jackson with his conscience and an assortment of week of uninhibited fun and debauchery who must help her addict daughter Molly Harper, “The Good Place”), who break up enemies as he tries to complete his latest after befriending a thrill-seeking couple (Mila Kunis, “Black Swan”) through four days before her sister’s wedding but decide job. -

Thomas Byrne Edsall Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4d5nd2zb No online items Inventory of the Thomas Byrne Edsall papers Finding aid prepared by Aparna Mukherjee Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2015 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory of the Thomas Byrne 88024 1 Edsall papers Title: Thomas Byrne Edsall papers Date (inclusive): 1965-2014 Collection Number: 88024 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 259 manuscript boxes, 8 oversize boxes.(113.0 Linear Feet) Abstract: Writings, correspondence, notes, memoranda, poll data, statistics, printed matter, and photographs relating to American politics during the presidential administration of Ronald Reagan, especially with regard to campaign contributions and effects on income distribution; and to the gubernatorial administration of Michael Dukakis in Massachusetts, especially with regard to state economic policy, and the campaign of Michael Dukakis as the Democratic candidate for president of the United States in 1988; and to social conditions in the United States. Creator: Edsall, Thomas Byrne Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover -

Hollywood Greats Flocked to Racquet Club West

Hollywood Greats Flocked To Racquet Club West By Don Soja An “official” neighborhood since 2007, the famed Racquet Club West (RCW) was once in the thick of all things “Hollywood” in Palm Springs. Sitting behind the notorious Racquet Club founded by two tennis-addicted actors, Ralph Bellamy and Charles Farrell (who had been politely asked to vacate the courts at the El Mirador Hotel, or so it’s said) the location made adjacent homes attractive to the hottest celebrities of the period. Dinner and dancing, drinks at poolside or sets of tennis were but a short walk or bike ride to the club. (Aside: Bicycles hadn’t been “adult toys” since the 1890’s but were re-popularized in Palm Springs. True.) At any given time, if you could bypass vigilant guards, you’d see Clark Gable, heartthrob Tyrone Power, Doris Day, Kirk Douglas, dancer Ann Miller, honeymooners Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Spencer Tracy or Bob Hope. This neighborhood was also rife with major producers, directors and screenwriters. Tucked between the two major north/south corridors of the town (Palm Canyon and Indian Canyon drives), Racquet Club West is bordered by West San Rafael Road on the north and San Marco Way and Alvarado Road on the south. This mix of 175 one- or two-bedroom villas, unprepossessing weekend cottages, charming Spanish casas, and homes by famed architect Don Wexler and the Alexanders is said to have inspired Raymond Chandler’s book Poodle Springs. The number of Top 100 American Movies, created here poolside and “over a highball” is astonishing. -

Ridley Scott's Dystopia Meets Ronald Reagan's America

RIDLEY SCOTT’S DYSTOPIA MEETS RONALD REAGAN’S AMERICA: CLASS CONFLICT AND POLITICAL DISCLOSURE IN BLADE RUNNER: THE FINAL CUT Fabián Orán Llarena Universidad de La Laguna “The great owners ignored the three cries of history. The land fell into fewer hands, the number of dispossessed increased, and every effort of the great own- ers was directed at repression.” (John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath) Abstract Blade Runner has been the object of multiple inquiries over the last three decades. However, this essay analyzes the socio-political discourse of the text, one aspect yet to be elucidated. Taking as basis the 1992 re-edited version (Blade Runner: The Final Cut), the essay studies the film as a critical and contextualized response to Ronald Reagan’s presidency (1981-1989). The essay scrutinizes how the materiality of the socio-economic system presented in the film, and the discourses that revolve around it, embody a critical representation of the policy-making and cultural discourse of Reaganism. Thus, the ensuing text characterizes the film as a (counter) 155 narrative that deconstructs the conservative ideology of the 1980s. Keywords: Reaganism, supply-side theory, hegemony, underclass, Off World. Resumen Blade Runner ha sido objeto de múltiples consideraciones durante las últimas tres décadas. No obstante, este ensayo analiza el discurso político-cultural del film, un aspecto aún por dilucidar. Tomando como base el remontaje de 1992 (Blade Runner: The Final Cut), se estudia el film como una respuesta crítica y contextualizada a la presidencia de Ronald Reagan (1981-1989). El ensayo escruta cómo la materialidad del sistema socio-económico presentado en el film, y los discursos que se construyen en torno al mismo, son una representación crítica de las políticas y el discurso cultural del Reaganismo.