Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Extraordinary Life of Josef Ganz The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NUDNIK Forgetting Josef Ganz Rémy Markowitsch

NUDNIK Forgetting Josef Ganz Rémy Markowitsch Maikäfer (From the Photo Archive of Josef Ganz, 1930-1933) Rémy Markowitsch Nudnik: Forgetting Josef Ganz Combining sculptural and multimedia works and archival ma- terials, the spatially expansive installation Nudnik: Forgetting Josef Ganz by Swiss artist Rémy Markowitsch deals with the Jewish engineer and journalist Josef Ganz. The artist presented his works in a cabinet space with two connecting corridors at the 2016 exhibition Wolfsburg Unlimited: A City as World La- boratory, the first show curated by Ralf Beil at Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg. The work consists not just of an aesthetic transfe- rence of Ganz’s photographic negatives and written documents to a presentation of large prints or as a video, but by way of the artist’s associative approach represents, as it were, the transil- lumination and “defoliation” of the history of a major figure in the automobile industry of the twentieth century, a figure ba- rely known until now. The processes of defoliation and transillumination, ex- posing hidden narratives, (material) conditions, and webs of relations, are defining aspects of Rémy Markowitsch’ s artistic approach. Driven in his work by certain stories, biographies, and literatures, since 1993 the artist has revealed the results of his research in photographic transilluminations. Just as the term from the realm of radiology describes, the relevant motif is penetrated, x-rayed, and superimposed with a different mo- tif. At the very moment when the photographic images shift from an opaque to a lucid state, they overlap one another. In Moving Forward so doing, the support material moves to the foreground, mat- rix dots become visible as grains and the representation is no longer focused on the act of illustration, but encourages simul- taneous examination. -

Drachepost Nr. 67 Vom Dezember 2020

DRACHE POSTNr. 67 l DEZEMBER 2020 Auf den Spuren des VW-Käfers Unsere Vereine in der Es ist keine Weihnachtsgeschichte aber unter dem Adventstürchen 24 Covid-19-Pandemie finden Sie den spannenden Bericht zum Titelbild der aktuellen Aus- Wie gehen sie damit um? Was geht gabe der Drachepost. noch und auf was musste verzich- Der Wichtracher Lorenz Schmid erzählt hier von seinen Recherchen tet werden? Wir haben nachge- über Josef Ganz, den wahren Erfinder des VW-Käfer-Konzepts. Die Ge- fragt und von einigen eine Ant- schichte führt uns zurück bis zum zweiten Weltkrieg. wort erhalten. Mehr dazu lesen Sie ab Seite 28 Mehr dazu lesen Sie ab Seite 12 2 l DRACHEPOST 67/20 Lukas Mani Heimelige Lokalitäten für Ihre Familien- und Klubanlässe Bergführer Obst-Baumschnitt Mittwoch ganzer Tag und Umweltingenieur Donnerstag bis 17 Uhr Unser Hit, geschlossen preisgünstig www.maniamwerk.ch und gut Familie Büttiker +41 (0)79 702 54 18 Telefon 031 781 02 20 Mani am Werk [email protected] Güggeli im Chörbli www.loewen-wichtrach.ch Corinne Lehmann Eicheweg 8 / 3114 Wichtrach / Tel. 031 782 15 01 KOMPETENTER PLANEN BESSER BAUEN GEPFLEGTER GENIESSEN DRACHEPOST 47 DRACHEPOST 67/20 l 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis Informationen aus dem Gemeinderat 4 Die AHV-Zweigstelle informiert 5 Das Erscheinungsbild der Gemeinde 6 Die Poststelle im Gesundheitszentrum Riesen 7 TGW Wichtrach – Das Interview mit Luca 7 Neues Probelokal für die Musikgesellschaft 9 zVg Projekt ENS – Fazit Mitwirkung 10 Liebe Wichtracherinnen Steel Darts Aaretal – ein neuer Verein stellt sich vor 11 und Wichtracher Unsere Vereine und deren Umgang mit Corona 12 Ein Editorial zu Ende eines Jahres erlaubt ei- nen Jahresrückblick. -

Press Release

April 4 2017 The Hague, the Netherlands / Bern, Switzerland PRESS RELEASE Rebuilding original 1933 VW Beetle forerunner Crowdfunding project aims to rebuild the original «Volkswagen» of Jewish engineer Josef Ganz The Hague, the Netherlands / Bern, Switzerland – Unique crowdfunding project aims to restore the original «Volkswagen» developed by Jewish engineer Josef Ganz and presented before Adolf Hitler at the 1933 Berlin motor show. Fast forward five years: Hitler introduces the Volkswagen to the German people while the Nazis deliberately erased Josef Ganz from the pages of history. Only surviving car This project is initiated by Paul Schilperoord from the Netherlands, writer of the book The Ex- traordinary Life of Josef Ganz – The Jewish Engineer Behind Hitler’s Volkswagen, and Lorenz Schmid, a Swiss-born relative of Josef Ganz. Together, we secured the only surviving rolling chassis of Josef Ganz’s «Volkswagen»: the Standard Superior type I. An estimated number of around 250 cars were built in April to September 1933. Presentation at Louwman Museum Our car survived as it was kept on the road in East Germany for decades, but the bodywork has been largely modified using Trabant parts. Working with professional restorers, we want to rec- reate the original wooden bodywork of this car – and use the car to promote the work of the for- gotten genius Josef Ganz. We aim to unveil the finished car in 2018 during a special event at the prestigious Louwman Museum in The Hague, the Netherlands. Milestone in automotive history The Standard Superior is the embodiment of Josef Ganz‘s propaganda campaign «For the German Volkswagen». -

Tatra As the Modern World Symbol by Ivan Margolius

The Friends of Czech Heritage Newsletter Issue 18 - Winter/Spring 2018 Tatra as the Modern World Symbol by Ivan Margolius The Strahov Stadium Images clockwise from lower left opposite: the teenage girls' display at the Spartiakad of 1985; the stadium today; two images of possible re-use of the Stadium, designed by Veronika Indrová Tatra Cars Above, archive image of Kopřivnice (German: Nesselsdorf), Moravia, in continuous automotive vehicle production since 1897. Right, Hans Ledwinka (1878 -1967) in front of his Tatra T87 car; left, the Tatra T11 10 The Friends of Czech Heritage Newsletter Issue 18 - Winter/Spring 2018 Tatra as the Modern World Symbol Hukvaldy, painter Alfons Mucha in Ivančice, by Ivan Margolius shoemaker Tomáš Baťa in Zlín, philosopher Edmund Husserl, and the inventor of contact lenses The Tatra company, the producer of world- Otto Wichterle in Prostějov, and Emil Zátopek in renowned innovative, streamlined cars, based in Kopřivnice. Ledwinka himself was not born in Kopřivnice (in German Nesselsdorf), Moravia, the Moravia but near Vienna, although his father Anton Czech Republic, has been in continuous automotive came from Brtnice. vehicle production since 1897 and as such belongs to one of the oldest car manufacturers in the world. Its In 1921 Ledwinka designed a radically innovative survival is due to the great technical mastery and Tatra T11 marketed as a ‘people’s car’ from 1923. talent of the people of Central Europe, and one man The new type was simple in construction, modest in in particular, Hans Ledwinka (1878-1967). maintenance, servicing and fuel consumption. The T11 consisted of an air-cooled, front two-cylinder Tatra started its existence in 1850 founded by Ignaz engine with a central tubular chassis which served as Schustala and from 1858 traded as Schustala & the carrier of the car body. -

RWTH Aachen Institut Für Geschichte, Theorie Und Ethik Der Medizin

RWTH Aachen Institut für Geschichte, Theorie und Ethik der Medizin Wendlingweg 2, D-52074 Aachen Tel.: 0241-80-88095; Fax: -82466 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://www.medizingeschichte.ukaachen.de; http:// www.medizinethik.ukaachen.de Letzter Bericht: 2015 Berichtszeitraum: Januar 2016- Dezember 2016 Wiss. Personal (Stand: 31.12.2016): Hauptamtliche und PD: Univ.-Prof. Dr. med. Dr. med. dent. Dr. phil. Dominik Groß (Inst. Dir.), apl. Prof. i. R. Dr. med. Heinz Rodegra, Priv.- Doz. Dr. med. Walter Bruchhausen, Dipl.-Theol., M.Phil. (wiss. Angest., Abwesenheitsvertreter), Dr. rer. medic. Stephanie Kaiser, M.A. (wiss. Angest.), Regina Müller, M.A. (10/2016-2/2017), Julia Nebe, M.A. (seit 9/2016), Dr. rer. medic. Mathias Schmidt, M.A. (wiss. Angest.), Priv.-Doz. Dr. med. Dagmar Schmitz (wiss. Angest.), Dr. phil. Ylva Söderfeldt, M.A. (wiss. Angest. bis 7/2016), Saskia Wilhelmy, M.A. (wiss. Angest.) Beschäftigte und Stipendiaten in Drittmittelprojekten, Volontäre und freie Mitarb.: Jan Kleinmanns, M.A. (WHK bis 4/2016, wiss. Angest. 5/2016-8/2016), Regina Müller, M.A. (WHK bis 9/2016), Julia Nebe, M.A. (WHK bis 8/2016), Tim Ohnhäuser, M.A. (wiss. Angest. bis 3/2016), Marystella Ramirez Guerra, MSc.(Oxon), MA, Lic. (Stipendiatin bis 4/2017), Vasilija Rolfes, M.A. (wiss. Angest. bis 3/2016), Enno Schwanke, M.A. (wiss. Angest. bis 6/2016), Jens Westemeier (wiss. Angest. seit 9/2016), Tina Winzen, M.A. (WHK bis 4/2017) Lehrbeauftragte: Priv.-Doz. Dr. med. Christoph Schweikardt, MA Studiengänge und -abschlüsse: Humanmed. (Modellstudieng.), Zahnmed. (Pflicht- u. Wahlpflichtveranstalt.), Gesch., Philos. (Veranstalt. -

Volkswagen Josef Ganz

THE THRILLING LIFE STORY OF JOSEF GANZ The first ever book on the extraordinary FALL 2011 life of the genius Josef Ganz, the unknown German counterpart to Henry Ford. A biography that reads like spy fiction and will attract a wide range of readers. The unique story of the German originator of THE E X T RAORDINARY LIFE O F compact car design whom the Nazis tried to erase from the official JOSEF GANZ record. THE JEWISH ENGINEER BEHIND H I TLER’ S Revelatory and a fun read, this is both an VOLKSWAGEN important piece of sup- pressed history and a real-life adventure story. The best that non-fiction has to offer. All the stunning facts the Nazis didn’t want the world to know. Paul Schilperoord THE THRILLING LIFE STORY OF JOSEF GANZ THE JEWISH DESIGNER THE NAZIS TRIED TO ERASE FROM HISTORY he astonishing biography of Josef a biography that reads like a spy thriller, T Ganz, a Jewish designer from Frank- he tells how Ganz was imprisoned by the furt, who in May 1931 created a revolu- Gestapo, until an influential friend with tionary small car: the Maikäfer (German connections to Göring helped secure his for May Beetle). Seven years later Hitler release. Soon afterwards he was forced to flee Germany while Porsche created Josef Ganz in a prototype of his Swiss Volkswagen (1937). Cigarette card showing Ganz’s introduced the Volkswagen. He not only Standard Superior (1933). ‘took’ the concept of Ganz’s family car, he even used the same nickname. To this day the VW Beetle is considered one of the most important of all auto- the Volkswagen for Hitler using many mobile designs. -

356 Registry Template 5/07

Hans Ledwinka, Kleinwagen Ingenieur terest in automotive engineering. Although his initial principal respon- sibility was to support railcar design, Ledwinka also was asked to pre- pare engineering drawings for the company’s new automobile, the Präsident. He worked under the guidance of another up-and-coming automotive engineer by the name of Edmund Rumpler who was but a half-dozen years his senior. Based on limited but successful production and sales of Präsident cars, Nesselsdorf management initiated design of a second model given the designation Type A. Edmund Rumpler and another engineer by the name of Karl Sage were given responsibility for developing the Model A B u i l d i n g T h e B r a n d transmission. Their efforts did not produce an acceptable product and both engineers left Nesselsdorf apparently as a result of their perceived Phil Carney failure. Ledwinka was then assigned responsibility for the transmission design and he devised one that incorporated four forward speeds and a steering column mounted shift lever. This accomplishment by the he mechanical elements used in the 356 Sportswagen trace young engineer did not go unnoticed and Hans Ledwinka was promoted directly back to Porsche’s engineer’s work on the Volkswagen. to head Nesselsdorf’s small automotive department at the age of twenty- TBut did all of the technical inspiration for the Volkswagen one. come from Professor Porsche and his team? Certainly Porsche and the With his promotion to department head perhaps Ledwinka thought people he directed can be credited with five years of effort to turn an at- he had sole responsibility for determining company direction for auto- tractive idea for cost-effective, reliable transportation into reality. -

Universidade Estadual Da Paraíba Campus Iii Centro De Humanidades Osmar De Aquino Departamento De Humanidades Curso De Licenciatura Plena Em História

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DA PARAÍBA CAMPUS III CENTRO DE HUMANIDADES OSMAR DE AQUINO DEPARTAMENTO DE HUMANIDADES CURSO DE LICENCIATURA PLENA EM HISTÓRIA ROBERTA DE BRITO SILVA UM PASSEIO PELA HISTÓRIA DO FUSCA: DO PROJETO QUASE ESQUECIDO PARA UM DOS MAIS DESEJADOS VEÍCULOS DO MUNDO (1934-1993) GUARABIRA - PB 2020 ROBERTA DE BRITO SILVA UM PASSEIO PELA HISTÓRIA DO FUSCA: DO PROJETO QUASE ESQUECIDO PARA UM DOS MAIS DESEJADOS VEÍCULOS DO MUNDO (1934-1993) Artigo apresentado como Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso – TCC à Universidade Estadual da Paraíba – UEPB Campus, lll Guarabira – PB, em cumprimento aos requisitos para obtenção do grau de Graduada em História, sob a orientação do Prof.º. Dr. Carlos Adriano Ferreira de Lima. GUARABIRA - PB 2020 É expressamente proibido a comercialização deste documento, tanto na forma impressa como eletrônica. Sua reprodução total ou parcial é permitida exclusivamente para fins acadêmicos e científicos, desde que na reprodução figure a identificação do autor, título, instituição e ano do trabalho. S586p Silva, Roberta de Brito. Um passeio pela história do Fusca [manuscrito] : do projeto quase esquecido para um dos mais desejados veículos do mundo (1934-1993) / Roberta de Brito Silva. - 2020. 40 p. : il. colorido. Digitado. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (Graduação em História) - Universidade Estadual da Paraíba, Centro de Humanidades , 2020. "Orientação : Prof. Dr. Carlos Adriano Ferreira de Lima , Coordenação do Curso de História - CH." 1. Carro do povo. 2. Fusca. 3. KDF-Wagen. 4. Automóvel. I. Título 21. ed. CDD 981 Elaborada por Andreza N. F. Serafim - CRB - 15/661 BSC3/UEPB ROBERTA DE BRITO SILVA UM PASSEIO PELA HISTÓRIA DO FUSCA: DO PROJETO QUASE ESQUECIDO PARA UM DOS MAIS DESEJADOS VEÍCULOS DO MUNDO (1934-1993) Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso apresentado em História da Universidade Estadual da Paraíba – UEPB, Campus III/Guarabira, em cumprimento aos requisitos para obtenção do grau de Graduada em História, sob orientação do Prof.º Dr. -

Art Mobil Salon Art Mobil Salon 8

ArtArt OrtOrt 021021 artart mobilmobil salonsalon JuliJuli 8.-11.8.-11. 15.-18.15.-18. 22.-25.22.-25. Dankeschön Wir danken unseren Förderern, der Stadt Heidelberg und dem Land Baden-Württemberg Wir danken der GBI Holding AG für die Ermöglichung der Zwischennutzung des ehemaligen Autohauses Wir danken Lichtblick GmbH, Köln, sowie Lorenz Schmid und Paul Schilperoord für die Recherchen zu Josef Ganz Wir danken der Familie Bernhardt für die Einblicke ins Familienalbum Wir danken der Firma Farben Hauck für die Bereitstellung der Farben für die Intervention von Georges Rousse Wir danken den Veranstaltungsfirmen CR-Projects, rent4event und der Firma fours für die technische Unterstützung Wir danken unserem Techniker- und Aushilfsteam für deren Einsatz Wir danken den eingeladenen KünstlerInnen Wir danken den engagierten PressevertreterInnen Wir danken der Firma Komplus, Horst Becker, für die Computer-Leihgabe Wir danken unserem Publikum, das uns stets zu neuen Ufern folgt „Man kann sagen, dass der Faschismus der alten Kunst zu lügen Sehr verehrtes Publikum, liebe Art Ort - FreundInnen, gewissermaßen eine neue Variante hinzugefügt hat - die teuflischste willkommen beim Heidelberger Klassiker der „Kunst im Öffentlichen Raum“, unserem inzwischen 15ten Variante, die man sich denken kann - nämlich: das Wahrlügen.“ Art Ort, diesmal ganz im Namen der viel besungenen „Mobilität“, zu der die Vergänglichkeit gehört. Freuen Sie sich mit uns auf die Helden der Arbeit, die Frauen und Männer der Tat, die Tüftler und „Spin- Hannah Arendt ner“, die, manchmal mit Glück, oft ohne, an ihren Ideen festhalten und diese verwirklichen, koste es, was es wolle. Wie in den 20er Jahren des letzten Jahrhunderts befinden wir uns wieder vor großem Wandel und weitgreifenden sozialen wie wirtschaftlichen Folgen bei rasant sichtbar werdenen sozial-politischen und klimatischen Veränderungen. -

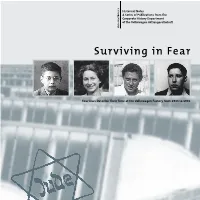

Surviving in Fear

Historical Notes A Series of Publications from the Corporate History Department of the Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft Historical Notes 3 Surviving in Fear Four Jews Describe Their Time at the Volkswagen Factory from 1943 to 1945 The authors Moshe Shen, born 1930 · Julie Nicholson, born 1922 · Sara Frenkel, born 1922 · Sally Perel, born 1925 · Susanne Urban, born 1968 Imprint Editors Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft Corporate History Department: Manfred Grieger, Ulrike Gutzmann Translation SDL Multilingual Services Design con©eptdesign, Günter Illner, Bad Arolsen Print Druckerei E. Sauerland, Langenselbold ISSN 1615-1593 ISBN 978-3-935112-22-2 © Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft Wolfsburg 2005 New edition 2013 Surviving in Fear Four Jews Describe Their Time at the Volkswagen Factory from 1943 to 1945 With a contribution by Susanne Urban Jewish Remembrance. Jewish Forced Labourers and Jews with False Papers at the Volkswagen Factory Susanne Urban _____ P. 6 Moshe Shen _____ P. 18 Julie Nicholson _____ P. 30 Jewish Remembrance. For Concentration Camp Inmates like us, Survival To Preserve History and Learn its Lessons is an Jewish Forced Labourers and Jews with False Papers was a Question of Time Essential Task at the Volkswagen Factory I. Forced labour at the Volkswagen factory Childhood and a strict father Sheltered childhood II. Structures of remembrance Too late to flee Arrested in Budapest III. Four lifelines Auschwitz Auschwitz The selection of prisoners for the Volkswagen factory Everyday life in Auschwitz Isolation and work on the “secret -

Disputing Volkswagen's Origins

While Ferdinand Porsche undoubtedly brought the Beetle to fruition, there are differing opinions as to whose ideas sparked the people’s car. Was it a sketch by Adolf Hitler, Porsche’s design ideas, influence from the third oldest car maker in the world: Tatra, or the design of a lesser-known Jewish engineer, Josef Ganz? Josef Ganz’s May Bug developed by the Nazis. Ferdinand Porsche drove Ganz’s prototype in 1931. I found a lot of evidence that all similar rear engines in the 1930s can be traced back to Ganz.” Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2086663/Hitler- copied-idea-iconic-Volkswagen-Beetle-Jewish-engineer-historian-claims. html#ixzz3G8jffXOe This interesting new theory will no doubt get VW enthusiasts talking! But there was yet another influential design source for the Beetle that has become so well-loved around the world. There is no question that Ferdinand Porsche designed the project that would become the early Beetle. However, a recent article published in the UK newspaper “Daily Mail” on January 15, 2012 suggests that a Jewish engineer, Josef Ganz, was exploring the idea of a people’s car as early as 1928. In fact, Ganz’s car, on display at a car show in 1933, was much closer to Hitler’s sketch, said to be given to Porsche in 1934. The better known Tatra History Tatra, a vehicle manufacturing company in Kopřivnice, Czech Republic, is the Hitler’s original Sketch and Ferdinand Porsche third oldest car maker in the world, behind Daimler and Peugeot. Tatra Chief Designer, Hans Ledwinka, was responsible for creating the T97, a smaller According to Daily Mail Reporter, Emma Reynolds, “The Nazi leader has alternative to the company’s T87 used by German officers during WWII for its always been given credit for sketching out the early concept for the car in a superior speed and handling on the Autobahn. -

Adolf Hitler Stole the Idea for the Iconic Volkswagen Beetle from a Jewish Engineer and Had Him Written out of History, a Historian Has Sensationally Claimed

Adolf Hitler stole the idea for the iconic Volkswagen Beetle from a Jewish engineer and had him written out of history, a historian has sensationally claimed. The Nazi leader has always been given credit for sketching out the early concept for the car in a meeting with car designer Ferdinand Porsche in 1935. His idea for the Volkswagen - or 'people's car' - is seen by many as one of the only worthwhile achievements of the genocidal dictator. Bug's life: Josef Ganz and his design, which Adolf Hitler saw at a car show in 1933, not long before he made his sketches for Ferdinand Porsche Gorgeous curves: One of Ganz's early drawings, which have been left buried in the past for many years 'People's car': Mr Ganz with one of his designs that author Paul Schilperoord says led up to the development of the Volkswagen But Paul Schilperoord's book, The Extraordinary Life of Josef Ganz - the Jewish engineer behind Hitler's Volkswagen, may change that forever. Hitler stipulated that the vehicle would have four seats, an air-cooled engine and cost no more than 1,000 Reichsmarks - the exact price that Mr Ganz said the car would cost. Three years before Hitler described 'his idea' to Mr Porsche in a Berlin hotel, Mr Ganz was driving a car he had designed called the Maikaefer, or May Bug. The lightweight, low-riding vehicle looked very like the Beetle that was later developed by Mr Porsche, who is still considered the foremost car designer in German history. Jewish inventor Mr Ganz had been exploring the idea for an affordable car since 1928 and made many drawings of a Beetle-like vehicle.