1. the Perception of Roman Past in Early Medieval Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baldwins of Lisnagat : Work in Progress

The Baldwins of Lisnagat : Work in Progress Alexandra Buhagiar 2014 CONTENTS Tables and Pictures Preamble INTRODUCTION Presentation of material Notes on material Abbreviations Terms used Useful sources of information CHAPTER 1 Brief historical introduction: 1600s to mid-1850s ‘The Protestant Ascendancy’ The early Baldwin estates: Curravordy (Mount Pleasant) Lisnagat Clohina Lissarda CHAPTER 2 Generation 5 (i.e. most recent) Mary Milner Baldwin (married name McCreight) Birth, marriage Children Brief background to the McCreight family William McCreight Birth, marriage, death Education Residence Civic involvement CHAPTER 3 Generation 1 (i.e. most distant) Banfield family Brief background to the Banfields Immediate ancestors of Francis Banfield (Gen 1) Francis Banfield (Gen 1) Birth, marriage, residence etc His Will Children (see also Gen 2) The father of Francis Banfield Property Early Milners CHAPTER 4 Generation 2 William Milner His wife, Sarah Banfield Their children, Mary, Elizabeth and Sarah (Gen. 3. See also Chapter 5) CHAPTER 5 Generation 3 William Baldwin Birth, marriage, residence etc Children: Elizabeth, Sarah, Corliss, Henry and James (Gen. 4. See also Chapter 6) Property His wife, Mary Milner Her sisters : Elizabeth Milner (married to James Barry) Sarah Milner CHAPTER 6 Generation 4 The children of William Baldwin and Mary Milner: Elizabeth Baldwin (married firstly Dr. Henry James Wilson and then Edward Herrick) Sarah Baldwin (married name: McCarthy) Corliss William Baldwin Confusion over correct spouse Property Other Corliss Baldwins in County Cork Henry Baldwin James Baldwin Birth, marriage, residence etc. Property His wife, Frances Baldwin CHAPTER 7 Compilation of tree CHAPTER 8 Confusion of William Baldwin's family with that of 'John Baldwin, Mayor of Cork' Corliss Baldwin (Gen 4) Elizabeth Baldwin (Gen 4) CHAPTER 9 The relationship between ‘my’ William Baldwin and the well documented ‘John Baldwin, Mayor of Cork’ family CHAPTER 10 Possible link to another Baldwin family APPENDIX 1. -

Irish Children's Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016

Irish Children’s Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016 A Thesis submitted to the School of English at the University of Dublin, Trinity College, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. February 2019 Rebecca Ann Long I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. _________________________________ Rebecca Long February 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………..i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………....iii INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………....4 CHAPTER ONE: RETRIEVING……………………………………………………………………………29 CHAPTER TWO: RE- TELLING……………………………………………………………………………...…64 CHAPTER THREE: REMEMBERING……………………………………………………………………....106 CHAPTER FOUR: RE- IMAGINING………………………………………………………………………........158 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………..……..210 WORKS CITED………………………….…………………………………………………….....226 Summary This thesis explores the recurring patterns of Irish mythological narratives that influence literature produced for children in Ireland following the Celtic Revival and into the twenty- first century. A selection of children’s books published between 1892 and 2016 are discussed with the aim of demonstrating the development of a pattern of retrieving, re-telling, remembering and re-imagining myths -

Stories from Early Irish History

1 ^EUNIVERJ//, ^:IOS- =s & oo 30 r>ETRr>p'S LAMENT. A Land of Heroes Stories from Early Irish History BY W. LORCAN O'BYRNE WITH SIX ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN E. BACON BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED LONDON GLASGOW AND DUBLIN n.-a INTEODUCTION. Who the authors of these Tales were is unknown. It is generally accepted that what we now possess is the growth of family or tribal histories, which, from being transmitted down, from generation to generation, give us fair accounts of actual events. The Tales that are here given are only a few out of very many hundreds embedded in the vast quantity of Old Gaelic manuscripts hidden away in the libraries of nearly all the countries of Europe, as well as those that are treasured in the Royal Irish Academy and Trinity College, Dublin. An idea of the extent of these manuscripts may be gained by the statement of one, who perhaps had the fullest knowledge of them the late Professor O'Curry, in which he says that the portion of them (so far as they have been examined) relating to His- torical Tales would extend to upwards of 4000 pages of large size. This great mass is nearly all untrans- lated, but all the Tales that are given in this volume have already appeared in English, either in The Publications of the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language] the poetical versions of The IV A LAND OF HEROES. Foray of Queen Meave, by Aubrey de Vere; Deirdre', by Dr. Robert Joyce; The Lays of the Western Gael, and The Lays of the Red Branch, by Sir Samuel Ferguson; or in the prose collection by Dr. -

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY of Macdhubhsith

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY OF MacDHUBHSITH ― MacDUFFIE CLAN (McAfie, McDuffie, MacFie, MacPhee, Duffy, etc.) VOLUME 2 THE LANDS OF OUR FATHERS PART 2 Earle Douglas MacPhee (1894 - 1982) M.M., M.A., M.Educ., LL.D., D.U.C., D.C.L. Emeritus Dean University of British Columbia This 2009 electronic edition Volume 2 is a scan of the 1975 Volume VII. Dr. MacPhee created Volume VII when he added supplemental data and errata to the original 1792 Volume II. This electronic edition has been amended for the errata noted by Dr. MacPhee. - i - THE LIVES OF OUR FATHERS PREFACE TO VOLUME II In Volume I the author has established the surnames of most of our Clan and has proposed the sources of the peculiar name by which our Gaelic compatriots defined us. In this examination we have examined alternate progenitors of the family. Any reader of Scottish history realizes that Highlanders like to move and like to set up small groups of people in which they can become heads of families or chieftains. This was true in Colonsay and there were almost a dozen areas in Scotland where the clansman and his children regard one of these as 'home'. The writer has tried to define the nature of these homes, and to study their growth. It will take some years to organize comparative material and we have indicated in Chapter III the areas which should require research. In Chapter IV the writer has prepared a list of possible chiefs of the clan over a thousand years. The books on our Clan give very little information on these chiefs but the writer has recorded some probable comments on his chiefship. -

The Phoenician Origin of Britons, Scots & Anglo-Saxons (1924

THE PHCENICIAN ORIGIN OF THE BRITONS, SCOTS &: ANGLO-SAXONS WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR. DISCOVERY OF THE LOST PALIBOTHRA OF THE GREEKS. With Plate. and Mape, Bengal Government Press,Calcutta, 1892.. "The discovery of the mightiest city of India clearly shows that Indian antiquarian studies are still in theirinfancy."-Engluhm4P1, Mar.10,1891. THE EXCAVATIONS AT PAUBOTHRA. With Plates, Plansand Maps. Government Press, Calcutta, 19°3. "This interesting ~tory of the discovery of one of the most important sites in Indian history i. [old in CoL. Waddell's RepoIt."-Timo of India, Mar. S, 1904· PLACE, RIVER AND MOUNTAIN NAMES IN THE HIMALAYAS. Asiatic Society, Calcutta, 1892.. THE BUDDHISM OF TIBET. W. H. Alien'" ce., London, 1895. "This is a book which considerably extends the domain of human knowledge."-The Times, Feb, 2.2., 1595. REPORT ON MISSION FOR COLLECTING GRECO-SCYTHIC SCULPTURES IN SWAT VALLEY. Beng. Govt. Pre.. , 1895. AMONG THE HIMALAYAS. Conetable, London, 1899. znd edition, 1900. "Thil is one of the most fascinating books we have ever seen."-DaU! Chro1Jiclt, Jan. 18, 1899. le Adds in pleasant fashion a great deal to our general store of knowledge." Geag"aphical Jau"nAI, 412.,1899. "Onc of the most valuable books that has been written on the Himalayas." Saturday Relliew,4 M.r. 189<}. wn,n TRIBES OF THE BRAHMAPUTRA VALLEY. With Plates. Special No. of Asiatic Soc. Journal, Calcutta, 19°°. LHASA AND ITS MYSTERIES. London, 19°5; 3rd edition, Methuen, 1906. " Rich in information and instinct with literary charm. Every page bears witness to first-hand knowledge of the country .. -

Proper Names

PROPER NAMES Acca 820 Aurunci 318 Achaeans 266 Ausoniae 41; Ausonii 253 Acheron 23 Achilles 9f., 14-28, 438; and Hector's Bacchus, and music 737 corpse 72-7; and Patroclus 42-58; Bellipotens 8 Achilles and ritual slaughter 82; death Bitias 396 anticipated 43, 45f., 54 Butes 690 Acoetes 30 Aconteus 612 Calydon 270 Adriatic, names for 405 Camilla 432; biography 535-96; name Aeneas 2; account of earlier events 113, 543; tomb 594; guilt 586; death 114; ancestry of 305; bonus I 06; 794-835; place of, in book xi, xiif. bound to kill Tu. 178f.; burial and corpse 892; vanity of 782 Aen. I 08 -19; commander 2-4, Caphereus 260 14 -28, 36; conflict of duties 94; Casmilla 543 deification of 125; Diomedes and Aen. Catillus 640 243-95; diplomacy of I 09; and des Chloreus 768 tiny 232; Evander and Aen. 152; Chromis 675 fama and arma of 124; father 184; Cicero 122-32 fights Tu. 434; good king I 06; Cloelia 535-96 Hector and Aen. 289; imperator 79, Clytius 666 446; just 126; magnanimity of 127; Coras 465; 604 mementoes of Dido 72-7; mourner Cybelo 768 39f., 42 58, 34; feeling for Pallas 36; Cyclopes 263 returns to narrative 904; victorious Cyrene 535-96 4; warrior 126; warrior hero 282fi; weeps 29, 41 Dardanidis 353 Aethon 89 Dardanium 472 Agamemnon 266ff. Demophoon 675 Amasenus 547 Dercennus 850 Amaster 673 Diana 535-96, 537, 591; vengeance of Amazon 648 857 Amazones Threiciae 659 Dido and cloaks given to A en. 72-7; Amazons 535-96, 571, Appx. -

Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung As a Junction Within Lebor Gabála Érenn

Edinburgh Research Explorer Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor Gabála Érenn Citation for published version: Thanisch, E 2013, Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor Gabála Érenn. in Quaestio Insularis: Selected Proceedings of the Cambridge Colloquium in Anglo-Saxon Norse and Celtic. vol. 13, pp. 69-93. <http://www.asnc.cam.ac.uk/publications/quaestio/Quaestio2012.html> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Quaestio Insularis General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor 1 Gabála Érenn INTRODUCTION Lebor Gabála Érenn: Content Lebor Gabála Érenn (‘the Book of the Invasion of Ireland’) is the conventional title for a lengthy Irish pseudo-historical text extant in multiple recensions probably compiled during the eleventh and twelfth centuries.2 The text comprises a history of the Gaídil (‘Gaels’) within the context of a universal history derived from the Bible and from Classical historiography.3 Lebor Gabála traces the ancestry of the Gaídil back to Noah and follows their tortuous migrations, spanning many generations, from the Tower of Babel to Ireland via Spain. -

Romano-Italic Relations and the Origins of the Social War

Managing Empire: Romano-Italic Relations and the Origins of the Social War by Owen James Stewart, BA (Hons) School of Humanities Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania February, 2019 STATEMENTS AND DECLARATIONS Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Owen James Stewart Date: 18/02/2019 Authority of Access This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Owen James Stewart Date: 18/02/2019 Statement Regarding Published Work Contained in Thesis The publisher of the paper comprising the majority of Chapter 1.4 (pages 29 to 42) hold the copyright for that content and access to the material should be sought from the respective journal. The remaining non-published content of the thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Owen James Stewart Date: 18/02/2019 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all those who served as my supervisor throughout this project: Geoff Adams, with whom it all began, for his enthusiasm and encouragement; Jonathan Wallis for substituting while other arrangements were being made; and Jayne Knight for her invaluable guidance that made submission possible. -

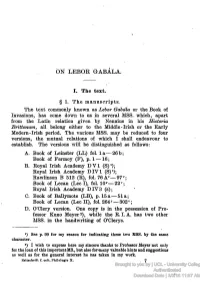

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

Faunus and the Fauns in Latin Literature of the Republic and Early Empire

University of Adelaide Discipline of Classics Faculty of Arts Faunus and the Fauns in Latin Literature of the Republic and Early Empire Tammy DI-Giusto BA (Hons), Grad Dip Ed, Grad Cert Ed Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy October 2015 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................... 4 Thesis Declaration ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 7 Context and introductory background ................................................................. 7 Significance ......................................................................................................... 8 Theoretical framework and methods ................................................................... 9 Research questions ............................................................................................. 11 Aims ................................................................................................................... 11 Literature review ................................................................................................ 11 Outline of chapters ............................................................................................ -

Aeneid 7 Page 1 the BIRTH of WAR -- a Reading of Aeneid 7 Sara Mack

Birth of War – Aeneid 7 page 1 THE BIRTH OF WAR -- A Reading of Aeneid 7 Sara Mack In this essay I will touch on aspects of Book 7 that readers are likely either to have trouble with (the Muse Erato, for one) or not to notice at all (the founding of Ardea is a prime example), rather than on major elements of plot. I will also look at some of the intertexts suggested by Virgil's allusions to other poets and to his own poetry. We know that Virgil wrote with immense care, finishing fewer than three verses a day over a ten-year period, and we know that he is one of the most allusive (and elusive) of Roman poets, all of whom wrote with an eye and an ear on their Greek and Roman predecessors. We twentieth-century readers do not have in our heads what Virgil seems to have expected his Augustan readers to have in theirs (Homer, Aeschylus, Euripides, Apollonius, Lucretius, and Catullus, to name just a few); reading the Aeneid with an eye to what Virgil has "stolen" from others can enhance our enjoyment of the poem. Book 7 is a new beginning. So the Erato invocation, parallel to the invocation of the Muse in Book 1, seems to indicate. I shall begin my discussion of the book with an extended look at some of the implications of the Erato passage. These difficult lines make a good introduction to the themes of the book as a whole (to the themes of the whole second half of the poem, in fact). -

The Wolf in Virgil Lee Fratantuono

The Wolf in Virgil Lee Fratantuono To cite this version: Lee Fratantuono. The Wolf in Virgil. Revue des études anciennes, Revue des études anciennes, Université Bordeaux Montaigne, 2018, 120 (1), pp.101-120. hal-01944509 HAL Id: hal-01944509 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01944509 Submitted on 23 Sep 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright ISSN 0035-2004 REVUE DES ÉTUDES ANCIENNES TOME 120, 2018 N°1 SOMMAIRE ARTICLES : Milagros NAVARRO CABALLERO, María del Rosario HERNANDO SOBRINO, À l’ombre de Mommsen : retour sur la donation alimentaire de Fabia H[---]la................................................................... 3 Michele BELLOMO, La (pro)dittatura di Quinto Fabio Massimo (217 a.C.): a proposito di alcune ipotesi recenti ................................................................................................................................ 37 Massimo BLASI, La consecratio manquée de L. Cornelius Sulla Felix ......................................... 57 Sophie HULOT, César génocidaire ? Le massacre des