Bonny and Read: Author's Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Board of Directors Zoom Meeting Summary Safety Issues

VOLUME XV, NO. 9 • SEPTEMBER 15, 2020 A PUBLICATION OF THE SOMERSET RUN CONDOMINIUM ASSOCIATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Zoom Meeting Summary Board of Directors Zoom Meeting Summary cover, 3 Safety Issues cover, 5 By Susan Gooen First Community Socially Distanced Event 4 [Editor’s Note: This article does not set forth the official minutes of the Resident Photographer Rick Fisher 4, 25 Association meeting. The official minutes are available on the Somerset Run Lifestyle Corner – Upcoming Events 5 website, once approved by the Board of Directors.] Weekly/Daily & Event Calendars 6, 7 Life on the Run 8 MONDAY, AUGUST 17, 2020 A Strange Segue: From Masks to Afghans 8, 9 The Open Board Meeting held on August 17 was streamed on Zoom due The Trivia Corner (Answers – 27) 9 to the COVID-19 epidemic. About 160 residents signed into the meeting. Board The Trivia Corner, Too (Answers – 27) 9 members Alan Blander, John Blazakis, Rick Blitz, Mike Goldman, Ed Gordon, Say Hello to Your New Neighbors 10 Fred Okun, and Danita Susi were present. Community Manager Monica Griffin and Assistant Community Manager Kaitlyn Brown also attended. The meeting Singles Club News 10 was called to order at 7 p.m. Somerset Run Seniors Bowling League 10 C&C News 10 MINUTES: Geology Tales 12 The minutes of the July 20, 2020 meeting were approved. Pool Countdown 12 TREASURER’S REPORT: Women’s Club News 12, 13 Ed Gordon reported that work on the 2021 budget has begun. The Budget Bocce in the Time of COVID-19 14 & Finance Committee, the team from First Service, Danita Susi, and Ed Gordon From the Frying Pan(s) into the Fire 14 were all involved in the process. -

Devil's Ballast

TEXT PUBLISHING TEACHING NOTES Devil’s Ballast MEG CADDY ISBN 9781925773460 RRP AU$19.99 Fiction RECOMMENDED READING AGE: 14+ Sign up to Text’s once-a-term education enewsletter for prizes, free reading copies and teaching notes textpublishing.com.au/education CURRICULUM GUIDE ABOUT THE AUTHOR The following teaching guide has been designed Meg Caddy is a bookseller by day and a boarding- to embrace shared curriculum values. Students are school tutor by night. Her first book, Waer, was encouraged to communicate their understanding shortlisted for the 2013 Text Prize and the 2017 CBCA of a text through speaking, listening, reading, writing, Children’s Book Awards. She lives with two rescue cats viewing and representing. and an ever-expanding bookshelf. The learning activities aim to encourage students to think critically, creatively and independently, to BEFORE READING reflect on their learning, and connect it to audience, 1. Have a class discussion inquiring about what purpose and context. They aim to encompass a students already know about pirates. This could range of forms and include a focus on language, include when they were most prominent, where they literature and literacy. Where appropriate, they mostly sailed and were they good or bad? How do include the integration of ICT and life skills. we view pirates now? 2. What qualities does a hero have? What qualities does a villain have? Make a list of defining traits SYNOPSIS before considering how these two archetypes can It’s the 18th century and pirates control most of the be similar and different. Caribbean. Irish woman Anne Bonny has escaped her 3. -

Personnages Marins Historiques Importants

PERSONNAGES MARINS HISTORIQUES IMPORTANTS Années Pays Nom Vie Commentaires d'activité d'origine Nicholas Alvel Début 1603 Angleterre Actif dans la mer Ionienne. XVIIe siècle Pedro Menéndez de 1519-1574 1565 Espagne Amiral espagnol et chasseur de pirates, de Avilés est connu Avilés pour la destruction de l'établissement français de Fort Caroline en 1565. Samuel Axe Début 1629-1645 Angleterre Corsaire anglais au service des Hollandais, Axe a servi les XVIIe siècle Anglais pendant la révolte des gueux contre les Habsbourgs. Sir Andrew Barton 1466-1511 Jusqu'en Écosse Bien que servant sous une lettre de marque écossaise, il est 1511 souvent considéré comme un pirate par les Anglais et les Portugais. Abraham Blauvelt Mort en 1663 1640-1663 Pays-Bas Un des derniers corsaires hollandais du milieu du XVIIe siècle, Blauvelt a cartographié une grande partie de l'Amérique du Sud. Nathaniel Butler Né en 1578 1639 Angleterre Malgré une infructueuse carrière de corsaire, Butler devint gouverneur colonial des Bermudes. Jan de Bouff Début 1602 Pays-Bas Corsaire dunkerquois au service des Habsbourgs durant la XVIIe siècle révolte des gueux. John Callis (Calles) 1558-1587? 1574-1587 Angleterre Pirate gallois actif la long des côtes Sud du Pays de Galles. Hendrik (Enrique) 1581-1643 1600, Pays-Bas Corsaire qui combattit les Habsbourgs durant la révolte des Brower 1643 gueux, il captura la ville de Castro au Chili et l'a conserva pendant deux mois[3]. Thomas Cavendish 1560-1592 1587-1592 Angleterre Pirate ayant attaqué de nombreuses villes et navires espagnols du Nouveau Monde[4],[5],[6],[7],[8]. -

When We Now Think of a Pirate's Flag We Think Of

Pirates with Ely Museum Pirate Flags When we now think of a pirate's flag we think of the "Skull and Cross Bones", however many pirates had their own unique designs that in their day would have been well known and would strike fear in the crew of a merchant ship if they saw it. To start with, many pirate ships did not have flags with designs on, instead they used different colour flags to say different things. A plain black flag had been used in the past to show a ship had plague on it and to stay away, so pirates started flying this to cause fear. However it also usually meant that the pirate would accept surrender and spare lives. Others used plain red flags, which dated back to English privateers who used it to show they were not Royal Navy, in pirate use this flag meant no surrender was accepted and no mercy would be shown! Over time pirates started adding their own designs to these plain coloured flags, these unique flags would soon become well known as the pirates reputation increased. Favourite things for pirates to have on their flags were skull, bones or sometimes whole skeletons, all meaning death and aiming to cause fear. They also often used images of swords, daggers and other weapons to show that they were ready to fight. An hourglass would mean that your time is running out as death was coming and a heart was used to show life and death. Jolly Roger Flag A flag would often be made up of one or more of those items and would sometimes include the Captain's initials or a simple outline of a figure depicting the Captain. -

Blood & Bounty

A short life but a merry one! A 28mm “Golden Age of Piracy” Wargame by DonkusGaming Version 1.0 Contents: Setting up a Game pg. 2 A very special “Thank You” to my art resources: Sequence of Play pg. 3 http://www.eclipse.net/~darkness/sail-boat-01.png https://math8geometry.wikispaces.com/file/view/protractor.gif/3 3819765/protractor.gif Vessel Movement Details pg. 7 http://brethrencoast.com/ship/sloop.jpg, Vessel Weapon Details pg. 8 http://brethrencoast.com/ship/brig.jpg, Vessel Weapons & Tables pg. 9 http://brethrencoast.com/ship/frigate.jpg, http://brethrencoast.com/ship/manofwar.jpg, Vessel Classes & Statistics pg. 11 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_ensign, Vessel Actions pg. 16 http://www.crwflags.com/fotw/flags/fr~mon.html, http://www.crwflags.com/fotw/flags/es~c1762.html, Crew Actions pg. 22 http://www.crwflags.com/fotw/flags/es_brgdy.html, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jolly_Roger, Crew Weapons (Generic) pg. 26 http://www.juniorgeneral.org/donated/johnacar/napartTD.png Crew Statistics pg. 29 https://jonnydoodle.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/alp ha.jpg http://www.webweaver.nu/clipart/img/historical/pirates/xbones- Famous Characters & Crews pg. 34 black.png Running a Campaign pg. 42 http://www.imgkid.com/ http://animal-kid.com/pirate-silhouette-clip-art.html Legal: The contents of this strategy tabletop miniatures game “Blood & Bounty” (excluding art resources where listed) are the sole property of myself, Liam Thomas (DonkusGaming) and may not be reproduced in part or as a whole under any circumstances except for personal, private use. They may not be published within any website, blog, or magazine, etc., or otherwise distributed publically without advance written permission (see email address listed below.) Use of these documents as a part of any public display without permission is strictly prohibited, and a violation of the author’s rights. -

Black Sails: La Edad De Oro De La Piratería En El Caribe

Facultat de Geografia i Història Treball fi de grau Black Sails: La Edad de Oro de la piratería en el Caribe Sergio López García Carrera de Historia NIUB: 16477646 Tutor: Dr. José Luís Ruíz Peinado Julio, 2017 Sergio López García Black Sails: La Edad de Oro de la piratería en el Caribe Black Sails: La Edad de Oro de la piratería en el Caribe. ÍNDICE 1. INTRODUCCIÓN ........................................................................................................... 3-6 2. DEBATE HISTORIOGRÁFICO: LA EDAD DE ORO DE LA PIRATERÍA .......... 6-10 3. CONTEXTO HISTÓRICO: PERIODOS DE LA EDAD DE ORO DE LA PIRATERIA ................................................................................................................................. 10-19 3.1 Periodo de los bucaneros (1650-1688) ................................................... 11-14 3.2 La Ronda del pirata (1690- 1700) ......................................................... 14-16 3.3 El periodo de la Guerra de Sucesión Española y consecuencias (1701-1720) ...... 16-19 4. PERSONAJES HISTÓRICOS ................................................................. 19-32 4.1 Piratas, corsarios, bucaneros y filibusteros ........................................... 22-28 4.2 Las mujeres piratas ................................................................................. 28-32 5. ISLAS Y REFUGIOS DE LOS PIRATAS .............................................. 32-39 5.1 Saint-Domingue: Isla Tortuga el primer asentamiento pirata ............ 32-36 5.2 New Providence: Nassau y la República -

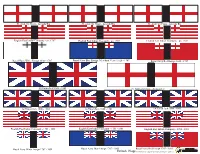

British Flags Permission to Copy for Personal Gaming Use Granted GAME STUDIOS

St AndrewsSt. Andrews Cross – CrossEnglish - Armada fl ag of the Era Armada Era St AndrewsSt. Andrews Cross – Cross English - Armada fl ag of the Era Armada Era St AndrewsSt. Andrews Cross – EnglishCross - flArmada ag of the Era Armada Era EnglishEnglish East IndianIndia Company Company - -pre pre 1707 1707 EnglishEnglish East East Indian India Company - pre 1707 EnglishEnglish EastEast IndianIndia Company Company - - pre pre 1707 1707 Standard Royal Navy Blue Squadron Ensign, Royal Navy White Ensign 1630 - 1707 Royal Navy Blue Ensign /Merchant Vessel 1620 - 1707 RoyalRoyal Navy Navy Red Red Ensign Ensign 1620 1620 - 1707 - 1707 1st Union Jack 1606 - 1801 St. Andrews Cross - Armada Era 1st1st UnionUnion fl Jackag, 1606 1606 - -1801 1801 1st1st Union Union Jack fl ag, 1606 1606 - 1801- 1801 1st1st Union Union fl Jackag, 1606 1606 - -1801 1801 English East Indian Company - 1701 - 1801 English East Indian Company - 1701 - 1801 English East Indian Company - 1701 - 1801 Royal Navy White Ensign 1707 - 1801 Royal Navy Blue Ensign 1707 - 1801 RoyalRed Navy Ensign Red as Ensignused by 1707 Royal - 1801Navy and ColonialSEA subjects DOG GAME STUDIOS British Flags Permission to copy for personal gaming use granted GAME STUDIOS . Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands Naval Jack Netherlands Naval Jack Netherlands Naval Jack Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag SEA DOG Dutch Flags GAME STUDIOS Permission to copy for personal gaming use granted. -

02 Battles of the Sevie Seas

Crossroads Middle School Writing Lab Publications Fall 2013 Argh! What ye may not fathom, matey, be that this book ye be holdin’ in yer scurvy paws be a rare treasure indeed. It be a wealth o’ pirate tales stolen directly from the lice- infested blowfish at Crossroads Middle School. The scallywag sea dog 7th graders be once again singin’ their sagas ‘bout legendary battles an’ seasoned buccaneers from bygone times. Therefore, consider yerself lucky that ye stumbled upon these accounts o’ bravery, scuffle, and plunder. Now, sit back with yer favorite salty parrot an’ a mug o’ grog an’ enjoy the regalin’ that be scribbled here. If’n ye don’t, prepare yer pox-faced, mutinous hide to be keelhauled lengthwise off a jolly pirate cutter. Savvy? ~The Treasures Within~ Captain Ty By: Captain Ty “Where’s Me Gold” Howard ………. Page 1 Captain Maggie Joller By: Scurvy Sarah “The Saber” Stefani ………. Page 2 The Stories Begin ………. Page 3 Bloody Scallyway By: Captain Jackson “Jack the Gentleman” Perry ………. Page 4 The Ship Battle of Death By: Dastardly Dizzy Izzy “Shoot My” Bowen ………. Page 6 Jolly Roger of: Captain Nayha “The Venomous Vet” Sengmanyphet ………. Page 10 The Battle of the Crew By: Captain Ty “Where’s Me Gold” Howard ………. Page 11 Why Now By: Commander Wesley “I’ll Make Ye Hole-ly” St. George ………. Page 14 Jolly Roger of: Scurvy Sarah “The Saber” Stefani ………. Page 16 Knight Halk By: Master Gunner “No-Eyed” Johnny ………. Page 17 Vanderpohl Jolly Roger of: Admirable Gabe “The Gab” Stewart ………. Page 19 The Best Pirate Battle of All Time!!! ………. -

Life Under the Jolly Roger: Reflections on Golden Age Piracy

praise for life under the jolly roger In the golden age of piracy thousands plied the seas in egalitarian and com- munal alternatives to the piratical age of gold. The last gasps of the hundreds who were hanged and the blood-curdling cries of the thousands traded as slaves inflated the speculative financial bubbles of empire putting an end to these Robin Hood’s of the deep seas. In addition to history Gabriel Kuhn’s radical piratology brings philosophy, ethnography, and cultural studies to the stark question of the time: which were the criminals—bankers and brokers or sailors and slaves? By so doing he supplies us with another case where the history isn’t dead, it’s not even past! Onwards to health-care by eye-patch, peg-leg, and hook! Peter Linebaugh, author of The London Hanged, co-author of The Many-Headed Hydra This vital book provides a crucial and hardheaded look at the history and mythology of pirates, neither the demonization of pirates as bloodthirsty thieves, nor their romanticization as radical communitarians, but rather a radical revisioning of who they were, and most importantly, what their stories mean for radical movements today. Derrick Jensen, author of A Language Older Than Words and Endgame Stripping the veneers of reactionary denigration and revolutionary romanti- cism alike from the realities of “golden age” piracy, Gabriel Kuhn reveals the sociopolitical potentials bound up in the pirates’ legacy better than anyone who has dealt with the topic to date. Life Under the Jolly Roger is important reading for anyone already fascinated by the phenomena of pirates and piracy. -

La Representación De Los Piratas En La Dragontea

BENEMÉRITA UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE PUEBLA FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS COLEGIO DE LINGÜÍSTICA Y LITERATURA HISPÁNICA “LA REPRESENTACIÓN DE LOS PIRATAS EN LA DRAGONTEA DE LOPE DE VEGA” TESIS PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO DE: LICENCIADA EN LINGÜÍSTICA Y LITERATURA HISPÁNICA PRESENTA PAULINA MASTRETTA YANES ASESOR MTRA. ALMA GUADALUPE CORONA PEREZ PUEBLA PUE. 2015 INDICE INTRODUCCIÓN ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 CAPÍTULO I CONTEXTO DE LA PIRATERÍA: LA PIRATERÍA ANTIGUA ......................................................................................................................................................................... 10 I.1 PIRATAS GRECOLATINOS ......................................................................................................... 10 I.2 EL TERROR DE LOS MARES: LOS VIKINGOS ..................................................... 13 I.4 LOS ÚLTIMOS PIRATAS DEL MEDITERRÁNEO ................................................. 17 I.5 MUJERES DESTACADAS EN LA PIRATERÍA ........................................................ 18 CAPITULO II CONTEXTO HISTÓRICO DE LA PIRATERÍA EN AMÉRICA ......................................................................................................................................................................... 30 II.1 LOS VIAJES DE EXPLORACIÓN Y EL DESCUBRIMIENTO DE AMÉRICA................................................................................................................................................................. -

The Pirates Christopher Condent an English Pirate Known for His Brutal Treatment of Prisoners, Sailed the Seas in the Early to Mid 1700’S

TM Rules The Pirates Christopher Condent An English pirate known for his brutal treatment of prisoners, sailed the seas in the early to mid 1700’s. His exploits ranged from the coast of Brazil to India and the Red Sea. He died in 1770. Jack Rackham Known as Calico Jack for the brightly colored coats and clothing he wore, Rackham was a classic Caribbean pirate, capturing small merchant vessels. After being pardoned once, he returned to piracy and was tried and hanged in Port Royal, Jamaica, in November of 1720. Henry Avery Sailing the Atlantic and Indian Oceans in the 1690’s, Avery was known at one time to be the richest pirate in the world. He is also famous for being one of the few pirates to retain his wealth and retire before either being killed in battle or tried and hanged. Emanuel Wynn This French Pirate is considered by many to be the first to fly the familiar skull and crossbones or ‘Jolly Roger’ flag. He also incorporated the image of an hourglass to tell his victims that time was running out. Playing the Game Goal: The goal of the game is to make three X’s out of your Pirate icons. Setting up the Game: You will need a large flat surface to play. Take the four Pirate Flag Cards (shown on page one) and shuffle them. Each player takes one and does not show it to the other players. The flag you drew is your icon. Keep this face down in front of you. Now, Ghost ship: A wild shuffle the deck and deal four cards face down to each player. -

'Standardized Chapel Library Project' Lists

Standardized Library Resources: Baha’i Print Media: 1) The Hidden Words by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 193184707X; ISBN-13: 978-1931847070) Baha’i Publishing (November 2002) A slim book of short verses, originally written in Arabic and Persian, which reflect the “inner essence” of the religious teachings of all the Prophets of God. 2) Gleanings from the Writings of Baha’u’llah by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 1931847223; ISBN-13: 978-1931847223) Baha’i Publishing (December 2005) Selected passages representing important themes in Baha’u’llah’s writings, such as spiritual evolution, justice, peace, harmony between races and peoples of the world, and the transformation of the individual and society. 3) Some Answered Questions by Abdul-Baham, Laura Clifford Barney and Leslie A. Loveless (ISBN-10: 0877431906; ISBN-13 978-0877431909) Baha’i Publishing, (June 1984) A popular collection of informal “table talks” which address a wide range of spiritual, philosophical, and social questions. 4) The Kitab-i-Iqan Book of Certitude by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 1931847088; ISBN-13: 978:1931847087) Baha’i Publishing (May 2003) Baha’u’llah explains the underlying unity of the world’s religions and the revelations humankind have received from the Prophets of God. 5) God Speaks Again by Kenneth E. Bowers (ISBN-10: 1931847126; ISBN-13: 978- 1931847124) Baha’i Publishing (March 2004) Chronicles the struggles of Baha’u’llah, his voluminous teachings and Baha’u’llah’s legacy which include his teachings for the Baha’i faith. 6) God Passes By by Shoghi Effendi (ISBN-10: 0877430209; ISBN-13: 978-0877430209) Baha’i Publishing (June 1974) A history of the first 100 years of the Baha’i faith, 1844-1944 written by its appointed guardian.