The English Creole of Panama. Publication No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perceptions of Dialect Standardness in Puerto Rican Spanish

Perceptions of Dialect Standardness in Puerto Rican Spanish Jonathan Roig Advisor: Jason Shaw Submitted to the faculty of the Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Yale University May 2018 Abstract Dialect perception studies have revealed that speakers tend to have false biases about their own dialect. I tested that claim with Puerto Rican Spanish speakers: do they perceive their dialect as a standard or non-standard one? To test this question, based on the dialect perception work of Niedzielski (1999), I created a survey in which speakers of Puerto Rican Spanish listen to sentences with a phonological phenomenon specific to their dialect, in this case a syllable- final substitution of [R] with [l]. They then must match the sounds they hear in each sentence to one on a six-point continuum spanning from [R] to [l]. One-third of participants are told that they are listening to a Puerto Rican Spanish speaker, one-third that they are listening to a speaker of Standard Spanish, and one-third are told nothing about the speaker. When asked to identify the sounds they hear, will participants choose sounds that are more similar to Puerto Rican Spanish or more similar to the standard variant? I predicted that Puerto Rican Spanish speakers would identify sounds as less standard when told the speaker was Puerto Rican, and more standard when told that the speaker is a Standard Spanish speaker, despite the fact that the speaker is the same Puerto Rican Spanish speaker in all scenarios. Some effect can be found when looking at differences by age and household income, but the results of the main effect were insignificant (p = 0.680) and were therefore inconclusive. -

Language and Dialect Contact in Spanish in New York: Toward the Formation of a Speech Community

LANGUAGE AND DIALECT CONTACT IN SPANISH IN NEW YORK: TOWARD THE FORMATION OF A SPEECH COMMUNITY RICARDO OTHEGUY ANA CELIA ZENTELLA DAVID LIVERT Graduate Center, University of California, Pennsylvania State CUNY San Diego University, Lehigh Valley Subject personal pronouns are highly variable in Spanish but nearly obligatory in many contexts in English, and regions of Latin America differ significantly in rates and constraints on use. We investigate language and dialect contact by analyzing these pronouns in a corpus of 63,500 verbs extracted from sociolinguistic interviews of a stratified sample of 142 members of the six largest Spanish-speaking communities in New York City. A variationist approach to rates of overt pro- nouns and variable and constraint hierarchies, comparing speakers from different dialect regions (Caribbeans vs. Mainlanders) and different generations (those recently arrived vs. those born and/ or raised in New York), reveals the influence of English on speakers from both regions. In addition, generational changesin constrainthierarchiesdemonstratethat Caribbeansand Mainlandersare accommodating to one another. Both dialect and language contact are shaping Spanish in New York City and promoting, in the second generation, the formation of a New York Spanish speech community.* 1. INTRODUCTION. The Spanish-speaking population of New York City (NYC), which constitutesmorethan twenty-five percent of the City’stotal, tracesitsorigins to what are linguistically very different parts of Latin America. For example, Puerto Rico and Mexico, the sources of one of the oldest and one of the newest Spanish- speaking groups in NYC respectively, have been regarded as belonging to different areasfrom the earliesteffortsat dividing Latin America into dialect zones(Henrı ´quez Uren˜a 1921, Rona 1964). -

Variation and Change in Latin American Spanish and Portuguese

Variation and change in Latin American Spanish and Portuguese Gregory R. Guy New York University Fieldworker:¿Que Ud. considera ‘buen español? New York Puerto Rican Informant: Tiene que pronunciar la ‘s’. Western hemisphere varieties of Spanish and Portuguese show substantial similarity in the patterning of sociolinguistic variation and change. Caribbean and coastal dialects of Latin American Spanish share several variables with Brazilian Portuguese (e.g., deletion of coda –s, –r). These variables also show similar social distribution in Hispanic and Lusophone communities: formal styles and high status speakers are consonantally conservative, while higher deletion is associated with working class speakers and informal styles. The regions that show these sociolinguistic parallels also share common historical demographic characteristics, notably a significant population of African ancestry and the associated history of extensive contact with African languages into the 19th C. But contemporary changes in progress are also active, further differentiating Latin American language varieties. Keywords: Brazilian Portuguese, Latin American Spanish, coda deletion, variation and change. 1. Introduction The Spanish and Portuguese languages have long been the objects of separate tradi- tions of scholarship that treat each of them in isolation. But this traditional separation is more indicative of political distinctions – Spain and Portugal have been separate nation-states for almost a millennium – than of any marked linguistic differences. In fact, these two Iberian siblings exhibit extensive linguistic resemblance, as well as no- tably parallel and intertwined social histories in the Americas. As this volume attests, these languages may very fruitfully be examined together, and such a joint and com- parative approach permits broader generalizations and deeper insights than may be obtained by considering each of them separately. -

Subject-Verb Word-Order in Spanish Interrogatives: a Quantitative Analysis of Puerto Rican Spanish1

Near-final version (February 2011): under copyright and that the publisher should be contacted for permission to re-use or reprint the material in any form Brown, Esther L. & Javier Rivas. 2011. Subject ~ Verb word-order in Spanish interrogatives: a quantitative analysis of Puerto Rican Spanish. Spanish in Context 8.1, 23–49. Subject-verb word-order in Spanish interrogatives: A quantitative analysis of Puerto Rican Spanish1 Esther L. Brown and Javier Rivas We conduct a quantitative analysis of conversational speech from native speakers of Puerto Rican Spanish to test whether optional non-inversion of subjects in wh-questions (¿qué tú piensas?) is indicative of a movement in Spanish from flexible to rigid word order (Morales 1989; Toribio 2000). We find high rates of subject expression (51%) and a strong preference for SV word order (47%) over VS (4%) in all sentence types, inline with assertions of fixed SVO word order. The usage-based examination of 882 wh-questions shows non-inversion occurs in 14% of the cases (25% of wh- questions containing an overt subject). Variable rule analysis reveals subject, verb and question type significantly constrain interrogative word order, but we find no evidence that word order is predicted by perseveration. SV word order is highest in rhetorical and quotative questions, revealing a pathway of change through which word order is becoming fixed in this variety. Keywords: word order, language change, Caribbean Spanish, interrogative constructions 1. Introduction In typological terms, Spanish is characterized as a flexible SVO language. As has been shown by López Meirama (1997: 72), SVO is the basic word order in Spanish, with the subject preceding the verb in pragmatically unmarked independent declarative clauses with two full NPs (Mallinson & Blake 1981: 125; Siewierska 1988: 8; Comrie 1989). -

Spanish-Based Creoles in the Caribbean

Spanish-based creoles in the Caribbean John M. Lipski The Pennsylvania State University Introduction The Caribbean Basin is home to many creole languages, lexically related to French, English, and—now only vestigially—Dutch. Surrounded by Spanish-speaking nations, and with Portuguese-speaking Brazil not far to the south, the Caribbean contains only a single creole language derived from a (highly debated) combination of Spanish and Portuguese, namely Papiamentu, spoken on the Netherlands Antilles islands of Curaçao and Aruba. If the geographical confines of the designation `Caribbean’ are pushed a bit, the creole language Palenquero, spoken in the Afro-Colombian village Palenque de San Basilio, near the port of Cartagena de Indias, also qualifies as a Spanish-related creole, again with a hotly contested Portuguese component. There are also a number of small Afro-Hispanic enclaves scattered throughout the Caribbean where ritual language, songs, and oral traditions suggest at least some partial restructuring of Spanish in small areas. Finally, there exists a controversial but compelling research paradigm which asserts that Spanish as spoken by African slaves and their immediate descendents may have creolized in the 19th century Spanish Caribbean—particularly in Cuba—and that this putative creole language may have subsequently merged with local varieties of Spanish, leaving a faint but detectable imprint on general Caribbean Spanish. A key component of the inquiry into Spanish-related contact varieties is the recurring claim that all such languages derive from earlier Portuguese-based pidgins and creoles, formed somewhere in West Africa1 and carried to the Americas by slaves transshipped from African holding stations, and by ships’ crews and slave traders. -

Panama's Dollarized Economy Mainly Depends on a Well-Developed Services Sector That Accounts for 80 Percent of GDP

LATIN AMERICAN SOCIO-RELIGIOUS STUDIES PROGRAM - PROGRAMA LATINOAMERICANO DE ESTUDIOS SOCIORRELIGIOSOS (PROLADES) ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RELIGIOUS GROUPS IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN: RELIGION IN PANAMA SECOND EDITION By Clifton L. Holland, Director of PROLADES Last revised on 3 November 2020 PROLADES Apartado 86-5000, Liberia, Guanacaste, Costa Rica Telephone (506) 8820-7023; E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.prolades.com/ ©2020 Clifton L. Holland, PROLADES 2 CONTENTS Country Summary 5 Status of Religious Affiliation 6 Overview of Panama’s Social and Political Development 7 The Roman Catholic Church 12 The Protestant Movement 17 Other Religions 67 Non-Religious Population 79 Sources 81 3 4 Religion in Panama Country Summary Although the Republic of Panama, which is about the size of South Carolina, is now considered part of the Central American region, until 1903 the territory was a province of Colombia. The Republic of Panama forms the narrowest part of the isthmus and is located between Costa Rica to the west and Colombia to the east. The Caribbean Sea borders the northern coast of Panama, and the Pacific Ocean borders the southern coast. Panama City is the nation’s capital and its largest city with an urban population of 880,691 in 2010, with over 1.5 million in the metropolitan area. The city is located at the Pacific entrance of the Panama Canal , and is the political and administrative center of the country, as well as a hub for banking and commerce. The country has an area of 30,193 square miles (75,417 sq km) and a population of 3,661,868 (2013 census) distributed among 10 provinces (see map below). -

Localizing Games for the Spanish Speaking World � Martina Santoro Okam Game Studio, Argentina Alejandro Gonzalez Brainz, Colombia

Localizing games for the Spanish Speaking World ! Martina Santoro Okam Game Studio, Argentina Alejandro Gonzalez Brainz, Colombia What you will hear in the next 22 mins. ●Introduction to Latin America ●How this world is diverse ●Difficulties you will find ●Overview of the Spanish speaking World ●How we approach localizing games for the region ●Case study: Vampire Season ●Some key considerations ●Wrap up Despite the difference, we have many of commonalities In contrast, western games work great in the region And how about payments • Credit card penetration is less than 15% • Mayor app store do not support carrier billing, and carriers in LATAM tend to want 60% - 70% of revenues and an integrator on top! This is the spanish speaking world Source: Wikipedia It’s the second natively spoken language spoken natively second the It’s 225,000,000 450,000,000 675,000,000 900,000,000 0 Mandarin (12%) Spanish (6%) English (5%) Hindi (4%) Arabic (3%) Portuguese (3%) Bengali (3%) Russian (2%) Japanese (2%) Source: Wikipedia And the third most used most third the And 1,200,000,000 300,000,000 600,000,000 900,000,000 0 Mandarin (15%) English (11%) Spanish (7%) Arabic (6%) Hindi (5%) Russian(4%) Bengali (4%) Portuguese (3%) Japanese (2%) Source: Wikipedia These are the biggest native spanish speaking countries speaking spanish native biggest the are These 120,000,000 30,000,000 60,000,000 90,000,000 Mexico Colombia Spain Argentina Peru Venezuela Chile Ecuador Guatemala Cuba Bolivia Dominican Republic Honduras Paraguay El Salvador Nicaragua Costa Rica Panama -

Exploring Traces of Andalusian Sibilants in US Spanish

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Hispanic Studies Honors Projects Hispanic Studies Spring 4-25-2018 El andaluz y el español estadounidense: Exploring traces of Andalusian sibilants in U.S. Spanish Carolyn M. Siegman Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/hisp_honors Part of the Anthropological Linguistics and Sociolinguistics Commons, Comparative and Historical Linguistics Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Phonetics and Phonology Commons, and the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Siegman, Carolyn M., "El andaluz y el español estadounidense: Exploring traces of Andalusian sibilants in U.S. Spanish" (2018). Hispanic Studies Honors Projects. 7. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/hisp_honors/7 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Hispanic Studies at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hispanic Studies Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Siegman 1 El andaluz y el español estadounidense: Exploring traces of Andalusian sibilants in U.S. Spanish By Carolyn Siegman Advised by Professor Cynthia Kauffeld Department of Spanish and Portuguese April 25, 2018 Siegman 2 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………....3 1.1 Andalucista Theory………………....…………………………………………6 1.2 Spanish in the United States…………………………………………………12 1.2.1 Contact with English……………………………………………….12 1.2.2 Contact Between Dialects of Spanish……………………………...15 2.0 Methodology………………………………………………………………………....19 2.1 Recordings……….…………………………………………………………..19 2.2 Elicitation Material...………………………………………………………...20 2.3 Speakers……………………………………………………………………...20 3.0 Analysis……………………………………………………………………………....25 3.1 Analysis of Andalusian Spanish……………………………………………..27 3.2 Analysis of Spanish in the United States…………………………………….40 3.3. -

Pronombres De Segunda Persona Y Fórmulas De Tratamiento En Español: Una Bibliografía Cuestiones Lingüísticas

.L i n g ü í s t i c a e n l a r e d . K o e l p a s u c s j i l g f s e 2 2 / 0 8 / 2 0 0 6 e i f l p w x c i r e a s l d l e y r t l m v u a w p x j c o u l p a w v e f h u s i z u p t g h z i jf ñ o i e ñ l ñ z p h p a w v e f d u M a u r o . A . F e r n á n d e z l e y r t l m a u g h p m v u a w p x j c o a i o l s l d l U n i v e r s i d a d . d e . A . C o r u ñ a w r e a p h p a w p j c . informaciones sobre Pronombres de segunda persona y fórmulas de tratamiento en español: una bibliografía cuestiones lingüísticas Introducción En el prefacio de una bibliografía de bibliografías sobre las lenguas del mundo, publicada en 1990, se hacía un llamamiento para una moratoria en la publicación de nuevos trabajos de este tipo, a no ser que respondiesen a una gran necesidad. Según el compilador, Rudolph Troike, con las tecnologías que en aquel entonces estaban ya a disposición de la comunidad científica, debería ser posible la confección de un único repertorio bibliográfico internacional, en formato electrónico, capaz de satisfacer incluso las necesidades más específicas de cualquier usuario imaginable. -

Dative Extension in Causatives: Faire-Infinitif in Latin American Spanish Michelle Sheehan (Anglia Ruskin University) 1

Dative extension in causatives: faire-infinitif in Latin American Spanish Michelle Sheehan (Anglia Ruskin University) 1. This paper attempts to model micro-parametric variation in Spanish causatives, with a special focus on Panamanian, Rioplatense, Costa Rican and Guatemalan Spanish, but drawing also on Mexican and Peninsular varieties. Data are from work with native informants backed up with large-scale questionnaires where possible, as well as the existing literature (on Mexican, Treviño 1993; Rioplatense, Bordelois 1974, 1988, Saab 2014; and Peninsular Spanish, Torrego 2010, Ordóñez 2008, Ordóñez and Roca 2014, Tubino Blanco 2010, 2011). 2. Case patterns in Spanish causatives are complicated substantially by the fact that some varieties, along with Portuguese, permit both ECM and faire-infinitif complements to hacer ‘make’ (with some restrictions – e.g., Panamanian, Mexican, Costa Rican and, for some speakers, Rioplatense) whereas others, along with French and Italian generally, permit only the faire-infinitif (e.g., Guatemalan Spanish). (1) a. Juan le/lo hizo comer manzanas. [C. Rican/Mexican/Panamanian] Juan him.DAT/.ACC= made eat apples b. Juan le/*lo hizo comer manzanas. [Guatemalan] Juan him.DAT/.ACCC= made eat apples ‘Juan made him eat apples.’ (2) Je lui/*l’ ai fait manger des carottes. [French] I him.DAT/.ACC= have made eat.INF of.the carrots ‘I made him eat carrots.’ The two constructions are clearly structurally distinct, however, as they are in other Romance varieties, with ECM permitting negation and banning clitic climbing, unlike faire-infinitif: (3) *La hice a Juan besar. [Panamanian] her.ACC made.1S DOM Juan kiss (4) Su falta de hambre *le/lo hizo [no comer la torta] [Rioplatense] his lack of hunger him.DAT/.ACC= made not eat.INF the cake ‘His lack of hunger made him not eat the cake.’ There is however variation amongst the varieties with respect to the possibility of ECM with: an inanimate causer and a non-pronominal causee. -

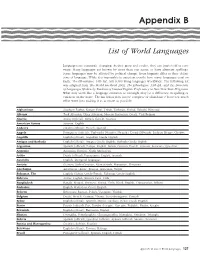

Bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages

Appendix B bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages Languages are constantly changing. As they grow and evolve, they can branch off or con- verge. Many languages are known by more than one name, or have alternate spellings. Some languages may be affected by political change. Even linguists differ in their defini- tions of language. While it is impossible to ascertain exactly how many languages exist on Earth, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., lists 6,809 living languages worldwide. The following list was adapted from The World Factbook 2002, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., and the Directory of Languages Spoken by Students of Limited English Proficiency in New York State Programs. What may seem like a language omission or oversight may be a difference in spelling or variation on the name. The list below may not be complete or all-inclusive; however, much effort went into making it as accurate as possible. Afghanistan Southern Pashto, Eastern Farsi, Uzbek, Turkmen, Brahui, Balochi, Hazaragi Albania Tosk Albanian, Gheg Albanian, Macedo-Romanian, Greek, Vlax Romani Algeria Arabic (official), French, Kabyle, Chaouia American Samoa Samoan, English Andorra Catalán (official), French, Spanish Angola Portuguese (official), Umbundu, Nyemba, Nyaneka, Loanda-Mbundu, Luchazi, Kongo, Chokwe Anguilla English (official), Anguillan Creole English Antigua and Barbuda English (official), Antigua Creole English, Barbuda Creole English Argentina Spanish (official), Pampa, English, Italian, German, French, Guaraní, Araucano, Quechua Armenia Armenian, Russian, North Azerbaijani -

Samuel Selvon and Linton Kwesi Johnson

Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue Moderne per la Comunicazione e la Cooperazione Internazionale Classe LM-38 Tesi di Laurea From the Caribbean to London: Samuel Selvon and Linton Kwesi Johnson Relatrice Laureanda Prof.ssa Annalisa Oboe Francesca Basso n° matr.1109406 / LMLCC Anno Accademico 2015 / 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ................................................................................................... 3 FIRST CHAPTER - HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ............................. 5 1. The Rise and the Fall of the British Empire: An Overview ..........................5 2. Caribbean Migration to Great Britain: From the 1950s to the 1970s .............9 3. White Rejection: From the 1950s to the 1970s........................................... 12 SECOND CHAPTER - THE MIGRANT FROM THE CARIBBEAN .. 19 1. Identity ..................................................................................................... 19 1.1. Theoretical Overview ....................................................................... 19 1.2. Caribbean Identity ............................................................................ 21 2. Language .................................................................................................. 29 3. “Colonization in Reverse” ......................................................................... 37 THIRD CHAPTER - SAMUEL SELVON............................................... 41 1. Biography ................................................................................................