Australia's Second World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPOT the DOG Canine Companions in Art EDUCATION RESOURCE CONTENTS

SPOT THE DOG canine companions in art EDUCATION RESOURCE CONTENTS 1. About this resource page 1 2. About this exhibition page 2 3. Meet the dogs page 5 4. Keys for looking page 10 5. Engaging students page 12 6. Post-visit activities page 14 7. Visiting the exhibition page 16 This Education Resource is produced in association with the exhibition Spot the Dog: canine companions in art presented by Carrick Hill, Adelaide from 8 March – 30 June 2017. Cover image: Narelle Autio, Spotty Dog (detail), 2001, Type C print, private collection. Acknowledgements Writer: Anna Jug, Associate Curator, Carrick Hill (with acknowledgement of research and text: Katherine Kovacic, Richard Heathcote and John Neylon). Design: Sonya Rowell, Carrick Hill. 1 ABOUT THIS EDUCATION RESOURCE This resource will provide information on the following: - a history of dogs in art that will contextualise the exhibition - how students may explore the themes of the exhibition - a list of questions and exercises designed to challenge students’ engagement with the work on display Year Level This resource is designed to be used in conjunction with a visit to Carrick Hill for students in upper primary and lower secondary students. It has been designed to correspond with the Australian Curriculum standards for Year 5 Band and above¹. Students will experience artworks from a range of cultures, times and locations. They explore the arts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and of the Asia region and learn that they are used for different purposes. Sections 4, 5 and 6 of this resource motivate student engagement with the work in the exhibition. -

Antique Bookshop

ANTIQUE BOOKSHOP CATALOGUE 304 The Antique Bookshop & Curios ABN 64 646 431062 Phone Orders To: (02) 9966 9925 Fax Orders to: (02) 9966 9926 Mail Orders to: PO Box 7127, McMahons Point, NSW 2060 Email Orders to: [email protected] Web Site: http://www.antiquebookshop.com.au Books Held At: Level 1, 328 Pacific Highway, Crows Nest 2065 Hours: 10am to 5pm, Thursday to Saturday All items offered at Australian Dollar prices subject to prior CHANGE OF BOOKSHOP OPENING DAYS sale. Prices include GST. Postage & insurance is extra. It seems of late that those customers who buy books from us increasingly Payment is due on receipt of books. do so by phone or email or directly through our web site, and we send the No reply means item sold prior to receipt of your order. books to them. Because of this we have decided to reduce the number of days we are open Unless to firm order, books will only be held for three days. during the week. From the week beginning Monday 7th March we will open from CONTENTS Thursday to Saturday inclusive, from 10am to 5pm each day. I know there are those who will always wish to see the books they are buy- BOOKS OF THE MONTH 1 - 33 ing and to browse so we will be available on those three days during the AUSTRALIA & THE PACIFIC 34 - 232 week, and if this is not convenient we can be open by appointment on any AVIATION 233 - 248 other weekday at a mutually convenient time. Please call us if you wish PARIS 249 - 268 to arrange this. -

Attitudes, Values, and Behaviour: Pastoralists, Land Use and Landscape Art in Western New South Wales

Attitudes, Values, and Behaviour: Pastoralists, land use and landscape art in Western New South Wales Guy Fitzhardinge February 2007 Revised February 2008 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Western Sydney © Guy Fitzhardinge 2007 Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree in this or any other institution Guy Fitzhardinge ii Acknowledgements My appreciation of the support, encouragement, wise council and efforts of Robert Fisher is unbounded. I also wish to acknowledge the support and encouragement of Tom Griffiths and Libby Robin and Robert Mulley. To my editor, Lindsay Soutar, my sincere thanks for a job well done. Many people – too many to name, have helped me and supported my efforts in a variety of ways and have made an otherwise difficult job so much easier. To all those people I wish to express my gratitude and thanks. Finally, to my wife Mandy, my deepest thanks for the sacrifices she has made during the writing of this thesis. Without her support this thesis would have not been possible. iii Table of Contents Statement of Authentication................................................................................................ii Acknowledgements............................................................................................................iii Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................iv -

Tobruk to Tarakan Book.Indb

TOBRUK to TARAKAN 70th Anniversary El Alamein Edition 2012 PUBLISHER’S NOTE by Paul Oaten Tobruk toTarakan: El Alamein 70th Anniversary Edition Since I was a young child, I have always had a keen interest in the 2/48th Battalion. Len Kader, my grandfather, was a member of this battalion and often spoke of the trials and tribulations of going to war. After his 1977 passing due to war wounds he received at El Alamein, I inherited photographs and memorabilia which inspired my passion for this historical event. Over the years, I have spoken to, and interviewed many of the original battalion veterans and relatives. These encounters have shown me a relaxed and funny side to some of the antics the Aussies got up to, while growing a respect for the hardships they dealt with. It has been an amazing journey for me. I have realised these were ordinary men, under extraordinary circumstances, who not only had a devotion to their country, but a devotion to each other. Their various ages and backgrounds did not matter as they saw each other as brothers. To me, it is very important that this amazing and accurate recollection of the 2/48th Battalion be republished for the 70th anniversary of the El Alamein battles. Some additional information and photographs I have accumulated over the years have been included. Many thanks to the veterans and relatives who so generously contributed. Lest we forget. Recommended Further Reading Churches, Ralph, 100Miles as the Crow Flies, 2000 (One of the Great Escapes of WWII) Dornan, Peter, The Last Man Standing, Allen and Unwin Farquhar, Murray, Derrick VC, Rigby Publishers, 1982 Fitzsimons, Peter, Tobruk, Harper Collins, 2006 Johnston, Mark, That Magnificent 9th: An Illustrated History of the Ninth Australian Division, Allen and Unwin, 2002 Spicer, Barry, Original Artwork www.barryspicer.com Stanley, Peter, Tarakan: An Australian Tragedy, Allen and Unwin, 1997 Wege, Anthony L., His Duty Done – The Story of SX7147 Corporal Harold Wilfred Gass. -

Cat179 Oct 2014

1 Catalogue 179 OCTOBER 2014 2 Glossary of Terms (and conditions) Returns: books may be returned for refund within 7 days and only if not as INDEX described in the catalogue. NOTE: If you prefer to receive this catalogue via email, let us know on [email protected] CATEGORY PAGE My Bookroom is open each day by appointment – preferably in the afternoons. Give me a call. Aviation 3 Abbreviations: 8vo =octavo size or from 140mm to 240mm, ie normal size book, 4to = quarto approx 200mm x 300mm (or coffee table size); d/w = dust Espionage 4 wrapper; pp = pages; vg cond = (which I thought was self explanatory) very good condition. Other dealers use a variety including ‘fine’ which I would rather leave to coins etc. Illus = illustrations (as opposed to ‘plates’); ex lib = had an Military Biography 6 earlier life in library service (generally public) and is showing signs of wear (these books are generally 1st editions mores the pity but in this catalogue most have been restored); eps + end papers, front and rear, ex libris or ‘book plate’; Military General 7 indicates it came from a private collection and has a book plate stuck in the front end papers. Books such as these are generally in good condition and the book plate, if it has provenance, ie, is linked to someone important, may increase the Napoleonic, Crimean & Victorian Eras 8 value of the book, inscr = inscription, either someone’s name or a presentation inscription; fep = front end paper; the paper following the front cover and immediately preceding the half title page; biblio: bibliography of sources used in Naval 9 the compilation of a work (important to some military historians as it opens up many other leads). -

The Web Publishing of the Notebooks and Diaries of CEW Bean

Digital preservation: the problems and issues involved in publishing private records online: the web publishing of the notebooks and diaries of C.E.W. Bean Robyn van Dyk Senior Curator Published and Digitised Records Australian War Memorial [email protected] www.awm.gov.au Abstract: In 2003, the Australian War Memorial commenced a project to digitise the notebooks and diaries of C.E.W. Bean for preservation and with the intent to make the images publicly available via the website. The digitisation of the records was completed in 2004, but the project ground to a halt when the copyright of this material was examined more closely and the records were found be a complex mixture of copyright rather than Commonwealth copyright. For the Memorial, this project represents our first venture into publishing a large complex collection of private records online and also our pilot for publishing orphan works using s200AB of the Copyright Act. Digital preservation and web publishing The Australian War Memorial is an experienced leader in digitisation for preservation and access. The Memorial has a digital preservation program that has now been in place for over a decade. We have digitised over two million pages of archival records to preservation level and for some time pursued a program of publishing these documents on our website. This serves to preserve the original documents and decreases the amount of staff resources required to service public enquiries for the most commonly used items. Publication of such material on the web has had very positive stakeholder feedback and perhaps more importantly, has not attracted any contentious comments. -

Monash and Chauvel

Two Great Australians who helped bring WW1 to an end - Monash and Chauvel 1918 finally saw the end of four long years of War in Europe and the Middle East. It had cost hundreds of thousands of lives including 60,000 Australians. Two of the chief army generals that helped bring about the final outcome were Sir John Monash and Sir Harry Chauvel – both Australians. Monash’s brilliant strategies brought the final victory on the Western Front and Chauvel led five brigades of Light Horse troops to carry out Allenby’s breakthrough plan and end the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East. General Sir John Monash – GCMG, KCB Monash was born on June 27, 1865 in West Melbourne. His father had migrated from Prussia in 1854. The family was Jewish and had changed the spelling of their name from Monasch to Monash. After his father’s business suffered great loss, the family moved to Jerilderie in New South Wales. John attended school there and displayed a high intellect and an extraordinary talent for mathematics. His family returned to Melbourne where he attended Scotch College in Glenferrie and became equal dux of the school, excelling in mathematics, before going on to study engineering, arts and law at Melbourne University. He was not a good student in his first year, being distracted by the things of the world, bored in lectures and he preferred to study at the State Library himself and attend the theatre. He failed his first year but then put his mind to it and flew through with honours. -

BE SUBSTANTIALLY GREAT in THY SELF: Getting to Know C.E.W. Bean; Barrister, Judge’S Associate, Moral Philosopher

BE SUBSTANTIALLY GREAT IN THY SELF: Getting to Know C.E.W. Bean; Barrister, Judge’s Associate, Moral Philosopher by Geoff Lindsay S.C. “That general determination – to stand by one’s mate, and to see that he gets a fair deal whatever the cost to one’s self – means more to Australia than can yet be reckoned. It was the basis of our economy in two world wars and is probably its main basis in peace time. Whatever the results (and they are sometimes uncomfortable), may it long be the country’s code”. C E W Bean, On The Wool Track (Sydney, 1963 revised ed.), p 132. [Emphasis added]. “Dr Bean’s achievements as historian, scholar, author and journalist are so well known that they need not be retold today…. He took as his motto for life the words of Sir Thomas Browne: “Be substantially thyself and let the world be deceived in thee as they are in the lights of heaven’. His wholeness lay in being at all times himself…. He believed that what men needed most were enlarged opportunities for work and service and that their failures and their wongheadedness sprang, not from the devil in them, but from lack of opportunity to do and to know better. From this belief came his lifelong interest in education. What a great headmaster was lost when he turned first to the law and then to journalism…”. Angus McLachlan, a printed Address (Eulogy) distributed with the Order of Service for CEW Bean’s funeral held at St Andrew’s Cathedral, Sydney, on 2 September 1968, following his death at Concord Repatriation Hospital on 30 August 1968. -

The Evolution of Australian Official War Histories David Horner

7 The Evolution of Australian Official War Histories David Horner Robert O’Neill was the third of Australia’s six official war historians, and directly or indirectly had a major influence on at least four of the official history series — his own and the three succeeding official histories. When O’Neill was appointed official historian for the Korean War in 1969, Australia had already had two official historians — Charles Bean and Gavin Long. O’Neill would need to draw on the experiences of his two successors, but also make his own decisions about what was needed for this new history. The two previous official histories provided much guidance. The first official historian, Charles Bean, was general editor and principal author of the Official History of Australia in the War of 1914– 1918, published between 1921 and 1942 in 15 volumes. This official history set the benchmark for later Australian official histories. Bean believed that his history had at least six objectives. First, it was largely a memorial to the men who had served and died. Second, he needed to record in detail what the Australians had done, in the belief that no other nation would do so. Third, the narrative needed to provide sufficient evidence to sustain the arguments presented in it. Fourth, as the war had been ‘a plain trial of national character, it was necessary to show how the Australian citizen reacted to it’. This meant that Bean needed to bring to life the experiences of the men in the front line. 73 WAR, StrategY AND HISTORY Fifth, Bean hoped that his history might ‘furnish a fund of information from which military and other students, if they desired, could draw’. -

Museums and History

Understanding Museums: Australian museums and museology Des Griffin and Leon Paroissien (eds) Museums and history In the years following World War II, history in Australian schools, universities and museums generally continued a long-standing focus on the country’s British heritage and on Australia’s involvement in war. However, by the 1970s Australia’s history and cultural development had begun to take a more important place in literature, in school curricula, and in universities, where specialised courses were providing training for future historians and museum curators. The essays in this section recount the way museums in Australia have dealt with crucial issues of the formation of national memory and identity. Contents Museums and history: Introduction, Leon Paroissien and Des Griffin War and Australia's museums, Peter Stanley History in the new millennium or problems with history?, Tim Sullivan Museums, history and the creation of memory, 1970–2008, Margaret Anderson Redeveloping ports, rejuvenating heritage: Australian maritime museums, Kevin Jones Museums and multiculturalism: too vague to understand, too important to ignore, Viv Szekeres Online version: http://nma.gov.au/research/understanding-museums/Museums_history.html Image credit: Ludwig Leichhardt nameplate, discovered attached to a partly burnt firearm in a bottle tree (boab) near Sturt Creek, between the Tanami and Great Sandy Deserts in Western Australia. Photo: Dragi Markovic. http://www.nma.gov.au/collections/highlights/the-leichhardt-nameplate Understanding Museums - Museums and history 1 http://nma.gov.au/research/understanding-museums/Museums_history.html National Museum of Australia Copyright and use © Copyright National Museum of Australia Copyright Material on this website is copyright and is intended for your general use and information. -

Lions Led by Donkeys? Brigade Commanders of the Australian Imperial Force, 1914-1918

LIONS LED BY DONKEYS? BRIGADE COMMANDERS OF THE AUSTRALIAN IMPERIAL FORCE, 1914-1918. ASHLEIGH BROWN A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy University of New South Wales, Canberra School of Humanities and Social Sciences March 2017 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Brown First name: Ashleigh Other name/s: Rebecca Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: MPhil School: Humanities and Social Sciences Faculty: UNSW Canberra, AD FA Title: Lions led by donkeys? Brigade commanders of the Australian Imperial Force, 1914-1918. Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Australian First World War historiography tends to focus on the ordinary soldier: his background, character and involvement in the war. This is a legacy left by Charles Bean who, following the history from below approach, believed in the need for soldiers’ stories to be told. On the other end of the spectrum, attention is given to political leaders and the British high command. British commanders and, by extension, other Allied commanders are too often portrayed as poor leaders who were reluctant to adapt to modern warfare, and did not demonstrate a sense of responsibility for the men under their command. The evidence shows that this perception is not accurate. A comprehensive understanding of the progression of Australian forces on the Western Front cannot be gained without investigating the progression of those in command. This thesis examines the brigade commanders of the Australian Imperial Force who held that level of command for a substantial period while on the Western Front. -

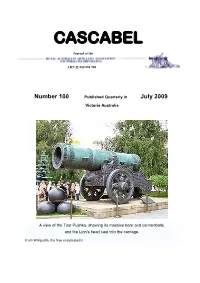

Issue100 – Jul 2009

CASCABEL Journal of the ABN 22 850 898 908 Number 100 Published Quarterly in July 2009 Victoria Australia A view of the Tsar Pushka, showing its massive bore and cannonballs, and the Lion's head cast into the carriage. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Article Pages Assn Contacts, Conditions & Copyright . 3 The President Writes . 5 Membership Report . 6 Notice of Annual General Meeting 7 Editor‘s Scratchings 8 Rowell, Sir Sydney Fairbairn (1894 - 1975) 9 A Paper from the 2001 Chief of Army's Military History Conference 14 The Menin Gate Inauguration Ceremony - Sunday 24th July, 1927 23 2/ 8 Field Regiment . 25 HMAS Tobruk. 26 Major General Cyril Albert Clowes, CBE, DSO, MC 30 RAA Association(Vic) Inc Corp Shop. 31 Some Other Military Reflections . 32 Parade Card . 35 Changing your address? See cut-out proforma . 36 Current Postal Addresses All mail for the Association, except matters concerning Cascabel, should be addressed to: The Secretary RAA Association (Vic) Inc. 8 Alfada Street Caulfield South Vic. 3167 All mail for the Editor of Cascabel, including articles and letters submitted for publication, should be sent direct to . Alan Halbish 115 Kearney Drive Aspendale Gardens Vic 3195 (H) 9587 1676 [email protected] 2 CASCABEL Journal of the FOUNDED: CASCABLE - English spelling. ABN 22 850 898 908 First AGM April 1978 ARTILLERY USE: First Cascabel July 1983 After 1800 AD, it became adjustable. The COL COMMANDANT: breech is closed in large calibres by a BRIG N Graham CASCABEL(E) screw, which is a solid block of forged wrought iron, screwed into the PATRONS and VICE PATRONS: breach coil until it pressed against the end 1978 of the steel tube.