Review: Marion Tauschwitz's Biography of Hilde Domin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P R E S S B O

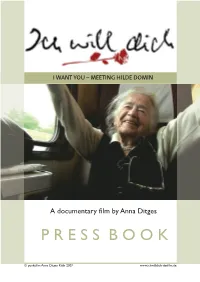

I WANT YOU – MEETING HILDE DOMIN A documentary fi lm by Anna Ditges P R E S S B O O K © punktfi lm Anna Ditges Köln 2007 www.ichwilldich-derfi lm.de I WANTBEGEGNUNGEN YOU – MEETING MIT HILDE HILDE DOMIN DOMIN CONTENTS The Film 3 Short Synopsis 4 Summary 5 Credits 8 Technical Details 9 An Interview with Anna Ditges 10 An Interview with Felix Kuballa 12 The Protagonist 14 Biography 15 Publications and Awards 16 The Director 17 Filmography 18 Contact / Impressum 19 Material Press English Subtitles CD (fi lm stills, set photography, texts) DVD (original version with English subtitles) © punktfi lm Anna Ditges Köln 2007 www.ichwilldichwww.ichwilldich-derfi lm.de 2 I WANTBEGEGNUNGEN YOU – MEETING MIT HILDE HILDE DOMIN DOMIN THE FILM “I want you - Meeting Hilde Domin” is a very personal and direct documentary fi lm about the life and work of poetess Hilde Domin: fi lm-maker Anna Ditges, almost 70 years younger than Domin, accompanied and fi lmed the Grande Dame of German post-war literature during the last two years of her long and eventful life. © punktfi lm Anna Ditges Köln 2007 www.ichwilldich-derfi lm.de 3 I WANTBEGEGNUNGEN YOU – MEETING MIT HILDE HILDE DOMIN DOMIN SHORT SYNOPSIS A young film-maker discovers Hilde Domin‘s lyric poetry and decides to get in touch with the celebrated poetess herself. She encounters a highly unconventional 95 year-old in an apartment full of books, roses and memories – with a life story that mirrors the last century. Hilde Domin, born in 1909, tells openly about her turbulent and troubled life: of her child- hood as an assimilated Jewess in Cologne, of more than two decades spent in exile, of the return to post-war Germany and her late career as a writer. -

Berg Literature Festival Committee) Alexandra Eberhard Project Coordinator/Point Person Prof

HEIDELBERG UNESCO CITY OF LITERATURE English HEIDEL BERG CITY OF LITERATURE “… and as Carola brought him to the car she surprised him with a passionate kiss before hugging him, then leaning on him and saying: ‘You know how really, really fond I am of you, and I know that you are a great guy, but you do have one little fault: you travel too often to Heidelberg.’” Heinrich Böll Du fährst zu oft nach Heidelberg in Werke. Kölner Ausgabe, vol. 20, 1977–1979, ed. Ralf Schell and Jochen Schubert et. al., Kiepenheuer & Witsch Verlag, Cologne, 2009 “One thinks Heidelberg by day—with its surroundings—is the last possibility of the beautiful; but when he sees Heidelberg by night, a fallen Milky Way, with that glittering railway constellation pinned to the border, he requires time to consider upon the verdict.” Mark Twain A Tramp Abroad Following the Equator, Other Travels, Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, 2010 “The banks of the Neckar with its chiseled elevations became for us the brightest stretch of land there is, and for quite some time we couldn’t imagine anything else.” Zsuzsa Bánk Die hellen Tage S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 2011 HEIDEL BERG CITY OF LITERATURE FIG. 01 (pp. 1, 3) Heidelberg City of Literature FIG. 02 Books from Heidelberg pp. 4–15 HEIDELBERG CITY OF LITERATURE A A HEIDELBERG CITY OF LITERATURE The City of Magical Thinking An essay by Jagoda Marinic´ 5 I think I came to Heidelberg in order to become a writer. I can only assume so, in retro spect, because when I arrived I hadn’t a clue that this was what I wanted to be. -

Mein Zerlesenstes Buch

Reden, Vorträge und Berichte . Mein zerlesenstes Buch Ein Dank an Hilde Domin Andreas F. Kelletat Wenn ich am Regal Ausschau halte nach jenem Buch, das nicht nur mehrfach gelesen sondern wirklich "zerlesen" ist, so gebührt dieser Lektürepreis einem von Hilde Domin Mitte der 60er Jahre konzipierten und umsichtig zusammengetragenen Band mit dem Titel Doppelinterpretationen. Das zeitgenössische deutsche Gedicht zwischen Autor und Leser. Die Fischer-Taschenbuchausgabe dieser Doppelinterpretationen kaufte ich 1972, als 17jähriger Schüler. Und lernte - auch später noch - sehr viel aus diesen Gedichten der 50er und 60er Jahre, die jeweils vom Autor selbst (von Peter Huchel, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Christoph Meckel oder Helmut Mader u.v.a.) und von einem Leser interpretiert wurden. Wobei es sich freilich um sehr professionelle Leser handelte, die Hilde Domin da zu "Interpretations-Doubletten" zusammengebracht hatte: Dichter wiederum und Kritiker und berühmte Germanisten und sogar der Heidelberger Philosoph Hans-Georg Gadamer, der sich auf Hilde Domins Lied zur Ermutigung II einließ. Der Hauptertrag des Zerlesens war für mich als Schüler: Gedichte kann man auf vielerlei Art lesen und zu verstehen suchen, es gibt nicht jene einzig "richtige" Interpretation, die wir in der Schule doch immer abliefern sollten. Und: Es kommt auf mich als Leser an, auf meine Mitarbeit - erst dann erschließt sich ein Gedicht und auch erst dann erschließt sich die Interpretation eines Gedichts. Hilde Domin scheint mir seit meiner ersten Lektüre Anfang der 70er eine Dichterin für junge Menschen zu sein. Das liegt vielleicht weniger an ihren Themen (denn die sind sehr vielfältig) und an ihrem entschiedenen Engagement für Verfolgte, Schwache und Zurückgestoßene als an einer Grundhaltung, über die sie in autobiographischen Texten selbst mehrfach gesprochen hat: Dass sie etwa Dinge sagt, die "man nicht sagt", dass sie gesellschaftliche Konventionen immer wieder schmerz- und lustvoll durchbricht, dass sie - um es modisch zu formulieren - eine authentische Existenz vorlebt. -

University of Illinois Modern Foreign Language Newsletter

405 Q Ul v. 23-27 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://www.archive.org/details/universityofilli2327univ UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AJ URSANA-CHAMPAIGN Twnfc &w* ' THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS MODERN FOREIGN LANGUAGE NEWSLETTER October, 1969 Director: Prof. Anthony M. Pasquariello Vol. XXIII, No. 1 Editor: Maxwell Reed Mowry, Jr. Dear Colleagues: In this first issue of the 23rd year of the University of Illinois Modern Foreign Language Newsletter, it is my privilege to send greetings to readers and colleagues throughout the state and to wish you all a successful year. A special welcome this year goes to Prof. Anthony M. Pasquariello, who on Sept. 1 assumed the headship of the Dept. of Spanish, Italian, & Portuguese at the U.I. He will also serve as Director of the Newsletter. He succeeds Prof. William H. Shoemaker in both capacities. At this point it would seem appropriate to salute Prof o Shoemaker for his long service both as department head and as Director of the Newsletter. All of his colleagues and friends will join me, I am sure, in thanking him and wishing him well. Two professors return to the Urbana campus after a year's sojourn in Europe. They are Prof. Francois Jost, who returns to direct again the Graduate Program in Comparative Literature, and Prof. Bruce Mainous, returning to his post as Head of the Dept. of French. Prof. Mainous spent the past year in Rouen, France, as Director of the Illinois-Iowa Year-Abroad Program; Prof. Jost spent a sabbatical year in Switzerland under the auspices of the Center for Advanced Study and also lectured at the Univ. -

4 Hilde Domin E Günter Eich – Due Idee Diverse Eppure Simili Di Poesia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Catalogo dei prodotti della ricerca UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI VERONA DIPARTIMENTO DI Dottorato in Letterature Straniere, Lingue e Linguistica SCUOLA DI DOTTORATO DI Scienze Umanistiche DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN Letteratura tedesca Con il contributo di (ENTE FINANZIATORE) Banco Popolare di Verona CICLO /ANNO (1° anno d’Iscrizione): 31 TITOLO DELLA TESI DI DOTTORATO Hilde Domin e la scrittura dell’impegno Gesellschaftskritik e questioni letterarie nei carteggi con Heinrich Böll, Günter Eich ed Erich Fried S.S.D. L-LIN/13 LETTERATURA TEDESCA Coordinatore: Prof./ Stefan Rabanus Firma __________________________ Tutor: Prof./Arturo Larcati Firma __________________________ Dottorando: Dott./Lorenzo Bonosi Firma 1 Quest’opera è stata rilasciata con licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione – non commerciale Non opere derivate 3.0 Italia . Per leggere una copia della licenza visita il sito web: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/it/ Attribuzione Devi riconoscere una menzione di paternità adeguata, fornire un link alla licenza e indicare se sono state effettuate delle modifiche. Puoi fare ciò in qualsiasi maniera ragionevole possibile, ma non con modalità tali da suggerire che il licenziante avalli te o il tuo utilizzo del materiale. NonCommerciale Non puoi usare il materiale per scopi commerciali. Non opere derivate —Se remixi, trasformi il materiale o ti basi su di esso, non puoi distribuire il materiale così modificato. Hilde Domin e la scrittura dell’impegno Gesellschaftskritik e questioni letterarie nei carteggi con Heinrich Böll, Günter Eich ed Erich Fried – Lorenzo Bonosi Tesi di Dottorato Verona, 30 maggio 2019 ISBN 9788869251566 2 Wer seine Ohnmacht eingesteht, kann mächtig sein. -

Hilde Domin. Una Voce Esiliata Torna Alle Sue Origini

Hilde Domin. Una voce esiliata torna alle sue origini di Silvia Alfonsi* Abstract: The essay traces the significant phases of Hilde Domin’s life as a German Jewish exile. Recognized as a great poet, she also left interesting theoretical writings on Poetics and abundant autobiographical works in prose. Following her testimonies and the in-depth biog- raphy of Marion Tauschwitz, the essay highlights the main themes in her life and writings. L’opera di Hilde Domin (1909-2006) è assai ricca e diversificata: riconosciuta come grandissima autrice di poesie, è anche autrice di scritti teorici sulla Poetica e di abbondante prosa autobiografica1. Ho voluto mettere in rilievo delle fasi impor- tanti della sua formazione e alcuni passaggi della sua vita di esule ebrea tedesca, avvalendomi della preziosa e appassionata biografia di Marion Tauschwitz. Mentre alla luce delle sue stesse testimonianze, soprattutto sulla sua seconda nascita come autrice di poesie, ho cercato di chiarire cosa significhino per lei la patria come luo- go natio, la lingua come dimora, la poesia come auto salvataggio e oggetto di con- sumo, ma anche possibilità di oggettivare il mondo nominandolo in modo diverso e consentendo l’esperienza di un’altra dimensione del tempo. ʻImperdibile esilio/lo tieni con te/ti ci infili dentro/ripiegato labirinto/deserto/da portarsi ap- pressoʼ2. Ho scritto in qualche momento, quando già risiedevo a Heidelberg. Patria polo op- posto all’esilio? No, non è corretto: è l’esilio il polo opposto, la negazione. Non è un caso se dovendo parlare di Heimat comincio con l’esilio. Quasi fosse un surrogato di patria. -

SORRY, BUT: Remembering Hilde Domin

Stuart Friebert | SORRY, BUT: Remembering Hilde Domin Photo Credit: Alessandra Capodacqua 1 Midway through our trek in the 60s to interview a number of German poets for an anthology David Young and I hoped to publish as a textbook, we got off the train in Heidelberg. Disappointed we weren’t able to arrange visits with more than one woman, we were doubly eager to knock on Hilde Domin’s door. We crossed the Neckar to the north part of town, then huffed and puffed our way up | 1 Stuart Friebert | SORRY, BUT: Remembering Hilde Domin the “Philosopher’s Way” to find her modest house, its clean, Bauhaus lines a relief from traditional architecture. Surprising us with a firm, double-handed handshake, Hilde exuded a force field of energy to wobble you. Her cheerful, lilting voice kept you from thinking about anything except what might next issue from her lips. She swept us into her studio, where she’d already set out a pot of tea and some ginger-cake I’d read she loved making. “Let’s first replenish you,” she said, cutting us a slab of cake, “then have ourselves a good walk farther up Heidelberg’s famous — or some would say infamous –Philosophenweg, which I can see by your faces has already challenged you. I need to take a brisk walk daily to clear my muddled mind,” she added. “Besides, you want to be able to say, as any tourist would, that you took in the splendid view across the river at our castle in the center of the old town. -

Marion Tauschwitz, Hilde Domin: Dass Ich Sein Kann, Wie Ich Bin

Marion Tauschwitz, Hilde Domin: Dass ich sein kann, wie ich bin. Biografie. Mainz: André Thiele, 2011. 606 pp. 16,90 €. Hilde Domin (1909-2006) is not well-known outside Germany these days as a major twentieth-century poet. But that was not always the case, and Marion Tauschwitz’s lovingly written yet authoritative and detailed biography may well encourage a revival of interest. For those of us who knew Domin in her last decades, when accolades rolled in and she seemed a fixture in contemporary German letters, this book offers a sharp corrective on a life that was troubled in early years by extended exile, marital tensions, and near-constant sense of restless alienation. Born into a family of assimilated Jews “im großbürgerlichen Stil” (23) in Köln, Hilde Löwenstein began her university studies in Heidelberg in law but then switched to philosophy and attended the lectures of Karl Jaspers. While in Heidelberg she met Erwin Walter Palm, also Jewish, a southern-looking, “dandyhaft” man who, despite a successful career as an archaeologist and cultural historian, wrote poems and plays throughout his life that were never as successful as his wife’s were to become. Their marital life together was troubled almost from the start. For one thing, political developments were dire. The rise of Nazi influence forced the Palms to escape to Italy, where Erwin completed his Doktorarbeit on Ovid and Hilde taught German. They married in 1936 and escaped to England. When war threatened there, they arrived as refugees in the Dominican Republic, where they remained for most of the next eleven years. -

As Nature Never Intended by Hilde Domin

Wesleyan University The Honors College As Nature Never Intended by Hilde Domin Translated by Marianna Foos Class of 2008 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in German Studies Middletown, Connecticut April, 2008 2 Translator’s Note A journey of a thousand miles must begin with a single step, and the first and most crucial step in doing a translation thesis is choosing the book. As a biology major, I first considered finding a book about biology. It didn’t seem as if it would be difficult, as there are plenty of German and German-speaking biologists of note. As I began to research, however, I realized that even if I found a biological text, it would likely be rather dry, and I would be risking an ugly burnout if I lost interest. Beyond that, the most important texts were already in English. Even if I couldn’t do a biology text, I was still hoping for a non-fiction work. The idea to do a biography came to me because my favorite book is Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table, also a biography. The results were twofold: first, I started looking for biographies in particular, and second, influenced by the quality of Levi’s book, I set my standards extremely high. At the time I was in Germany, stopping at every used bookstore I could find and buying up books that seemed interesting, because I didn’t know when I would see them again. -

The Fate of Young Jewish Refugees from Nazi Germany

Walter Laqueur: Generation Exodus page A “This latest valuable addition to Walter Laqueur’s insightful and extensive chron- icle of European Jewry’s fate in the twentieth century is an exceedingly well- crafted and fascinating collective biography of the younger generation of Jews: how they lived under the heels of the Nazis, the various routes of escape they found, and how they were received and ultimately made their mark in the lands of their refuge. It is a remarkable story, lucidly told, refusing to relinquish its hold on the reader.” —Rabbi Alexander M. Schindler, President emeritus, Union of American Hebrew Congregations “Picture that generation, barely old enough to flee for their lives, and too young to offer any evident value to a world loath to give them shelter. Yet their achieve- ments in country after country far surpassed the rational expectations of conven- tional wisdom. What lessons does this story hold for future generations? Thanks to Walter Laqueur’s thought-provoking biography, we have a chance to find out.” —Arno Penzias, Nobel Laureate “Generation Exodus documents the extraordinary experiences and attitudes of those young Austrian and German Jews who were forced by the Nazis to emigrate or to flee for their lives into a largely unknown outside world. In most cases they left behind family members who would be devoured by the infernal machines of the Holocaust. Yet by and large, some overcoming great obstacles, some with the help of caring relatives or friends, or of strangers, they became valuable members of their adopted homelands. Their contributions belie their small numbers. -

Programme Philipp Schwartz and Inspireurope Stakeholder Forum

Programme Philipp Schwartz and Inspireurope Stakeholder Forum 26 - 27 April 2021, Virtual Conference 2 | Table of Contents & Agenda Table of Contents Agenda ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Philipp Schwartz Initiative & Academics in Solidarity ........................................................................... 3 Inspireurope ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Programme ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Virtual Lunchtime Fair ..................................................................................................................... 11 Speakers ........................................................................................................................................ 12 Coaches ........................................................................................................................................ 26 Alexander von Humboldt Foundation ............................................................................................... 30 The German Section of the Scholars at Risk Network ........................................................................ 31 Contact Information and Imprint .................................................................................................... -

Das Wort, Das Wirklichkeit Sucht

Zum 90. Geburtstag von Das Wort, Hilde Domin am 27. Juli das Wirklichkeit sucht Wolf Scheller Man hat sie eine Lyrik-Klassikerin ge- Mit ihrem Freund und späteren Ehe- nannt. Aber vor ihrem vierzigsten Le- mann, dem Kunsthistoriker Erwin Walter bensjahr hat Hilde Domin kein einziges Palm, emigrierte sie schon 1932 zunächst Gedicht geschrieben. Das Schreiben be- nach Rom, promovierte in Florenz über gann später. Die Jahre des Exils in Eng- die Staatstheorie in der Renaissance und land und in der Dominikanischen Repub- brachte schließlich auch ihre Eltern dazu, lik lagen hinter ihr. Aus der Kölner Jüdin rechtzeitig illegal nach Holland auszu- Hilde Palm war die Schriftstellerin Hilde wandern. Die Flucht vor dem Nationalso- Domin geworden. zialismus zwang sie zu einer abenteuer- Im Gespräch sagte sie einmal: „Seither lichen Odyssee, die sie in der Folge über ist Schreiben für mich wie Atmen: Man Paris und London schließlich nach Santo stirbt, wenn man es lässt . .“ Es war die- Domingo führte, von wo sie erst 1954 ser leicht pathetische Bekenntniston, der wieder nach Deutschland zurückkehrte. gelegentlich auch die Freunde der Domin Der kürzlich verstorbene Heidelberger irritierte. Aber sie hat ihr literarisches Philosoph Hans-Georg Gadamer hat Credo immer wieder zu Gehör gebracht, Hilde Domin als „Dichterin der Rück- die Wiederholung nicht scheuend, viel- kehr“ bezeichnet. Das mag ihr selbst auch leicht am deutlichsten in ihrer Dankes- eine sympathische Metapher gewesen rede zur Verleihung des Nelly-Sachs- sein. Doch bei Licht betrachtet, ist Hilde Preises 1983. Aber was sie sich unter der Domin damals vor ihren Landsleuten ge- Verteidigung oder Wiederbelebung der flohen, nicht vor ihrer Sprache.