F O U N D E D 1 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Anthropology Through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-Based Sentiment

Cultural Anthropology through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-based Sentiment Peter A. Gloor, Joao Marcos, Patrick M. de Boer, Hauke Fuehres, Wei Lo, Keiichi Nemoto [email protected] MIT Center for Collective Intelligence Abstract In this paper we study the differences in historical World View between Western and Eastern cultures, represented through the English, the Chinese, Japanese, and German Wikipedia. In particular, we analyze the historical networks of the World’s leaders since the beginning of written history, comparing them in the different Wikipedias and assessing cultural chauvinism. We also identify the most influential female leaders of all times in the English, German, Spanish, and Portuguese Wikipedia. As an additional lens into the soul of a culture we compare top terms, sentiment, emotionality, and complexity of the English, Portuguese, Spanish, and German Wikinews. 1 Introduction Over the last ten years the Web has become a mirror of the real world (Gloor et al. 2009). More recently, the Web has also begun to influence the real world: Societal events such as the Arab spring and the Chilean student unrest have drawn a large part of their impetus from the Internet and online social networks. In the meantime, Wikipedia has become one of the top ten Web sites1, occasionally beating daily newspapers in the actuality of most recent news. Be it the resignation of German national soccer team captain Philipp Lahm, or the downing of Malaysian Airlines flight 17 in the Ukraine by a guided missile, the corresponding Wikipedia page is updated as soon as the actual event happened (Becker 2012. -

Maryland Women's Heritage Trail

MARYLAND WOMEN’S HERITAGE TRAIL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 101112131415161718192021 A A ALLEGANY COUNTY WASHINGTON COUNTY CECIL COUNTY GARRETT COUNTY CARROLL COUNTY HARFORD COUNTY B B BALTIMORE COUNTY FREDERICK COUNTY C C BALTIMORE CITY KENT COUNTY D ollowollow thethe footstepsfootsteps HOWARD COUNTY D ollow the footsteps and wander the paths where in Southern Maryland, to scientists, artists, writers, FMaryland women have built our State through- educators, athletes, civic, business and religious MONTGOMERY COUNTY F QUEEN ANNE’S out history. Follow this trail of tales and learn about leaders in every region and community. Visit these ANNE ARUNDEL E COUNTY E the contributions made by women of diverse back- sites and learn about women’s accomplishments. COUNTY grounds throughout Maryland – from waterwomen Follow in the footsteps of inspirational Maryland on the Eastern Shore to craftswomen of Western women and honor our grandmothers, mothers, Maryland, to civil rights activists of Baltimore and aunts, cousins, daughters and sisters whose contri- F Central Maryland, to women who worked the land butions have shaped our history. F Washington D.C. TALBOT WESTERN MARYLAND REGION PRINCE GEORGE’S COUNTY ALLEGANY COUNTY Anna Eleanor Roosevelt Memorial Tree COUNTY CAROLINE G Chesapeake and Ohio (C&0) Canal National Historic Park Gladys Noon Spellman Parkway COUNTY G Jane Frazier House Adele H. Stamp Student Union Elizabeth Tasker Lowndes Home Mary Surratt House The Woodyard Archeological Site FREDERICK COUNTY CALVERT H Beatty-Creamer House H Nancy Crouse House CENTRAL MARYLAND REGION CHARLES COUNTY COUNTY Barbara Fritchie Home ANNE ARUNDEL COUNTY Hood College Annapolis High School Ladiesburg Banneker-Douglass Museum National Museum of Civil War Medicine DORCHESTER COUNTY Charles Carroll House of Annapolis National Shrine of Elizabeth Ann Seton Chase-Lloyd House Helen Smith House and Studio I Coffee House I Steiner House/Home of the WICOMICO COUNTY Government House Frederick Women’s Civic Club ST. -

Questioning Identity, Humanity and Culture Through Japanese Anime

The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan The Many Faces of Popular Culture and Contemporary Processes: Questioning Identity, Humanity and Culture through Japanese Anime Mateja Kovacic Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong 0434 The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2013 Official Conference Proceedings 2013 Abstract In a highly globalized world we live in, popular culture bears a very distinctive role: it becomes a global medium for borderless questioning of ourselves and our identities as well as our humanity in an ever-transforming environment which requires us to be constantly ''plugged in'' in order to respond to all the challenges as best as we can. Vast cultural products we create and consume every day thus provide a relevant insight into problems that both researchers and audiences have to face with in an informatised and technologised world. Japanese anime is one of such cultural products: a locally produced cultural artifact became a global phenomenon that transcends cultures and spaces. In its imageries we discover a wide range of themes that concern us today, ranging from bioethical issues, such as ecological crisis, posthumanism and loss of identity in a highly transforming world to the issues of traditionality and spirituality. The author will show in what ways we can approach and study popular culture products in order to understand the anxieties and prevailing concerns of our cultures today, with emphasis on the identity and humanity, and their position in the contemporary high-tech world we live in. The author's intention is to point to popular culture as a significant (re)source for the fields of humanities and cultural studies, as well as for discussing human transformations and possible future outcomes of these transformations in a technoscientific world. -

Barbara Hammer, 70 Years Old, Hands the Camera to Gina Carducci, a Young Queer Film- Maker

Generations is a film about mentoring and passing on the tradi- tion of personal experimental filmmaking. Barbara Hammer, 70 years old, hands the camera to Gina Carducci, a young queer film- maker. Shooting during the last days of Astroland at Coney Is- land, New York, the filmmakers find that the inevitable fact of ageing echoes in the architecture of the amusement park and in the emulsion of the film medium itself. Editing completely sep- arately both picture and sound, the filmmakers join their films in the middle when they’ve finished, making a true generational and experimental experiment. In a time when digital dominates the art domain, a DIY aesthet- ic is embraced by Gina Carducci, a young thirty-year-old filmmak- er who hand processes 16mm film and a seventy-year-old pioneer of queer experimental cinema, Barbara Hammer. Hammer invites Carducci to collaborate on a new film, Generations. Barbara Hammer Celebrating Hammer’s spontaneous shooting style and dense ed- Maya Deren’s Sink iting montage with Carducci’s studied cinematography, the two filmmakers, generations apart in age, shoot the last days of Astro- land in Coney Island, New York. The aged but vibrant amusement Eine Hommage an die Mutter des amerikanischen Avantgarde- park, characteristic of the 70-year-old Hammer, is a fitting envi- films. Der Film beschwört durch Gespräche mit WeggefährtInnen ronment for the photoplay of the two Bolex filmmakers. und ZeitgenossInnen den Geist einer überlebensgroßen Person. Teiji Itos Familie, Carolee Schneemann und Judith Malvina schwe- Inspired by the revolutionary Shirley Clarke film,Bridges Go ben durch Derens Wohnorte und erinnern sich an kleinste Details Round (1953), where Clarke printed the same footage twice us- der architektonischen und persönlichen Innenräume. -

Barbara Hammer – Technology of Touch Chapter 2

!1 ! The concerns of O’Neill’s first 15 years of filmmaking — the graphic qualities of the image, the role of stasis in the context of a time-based art form, and the process-based applications of technology in making art — are writ large in the second phase of his career, in which he shifted to 35mm for a series of extraordinarily accomplished feature-length films. In these films, which include Water and Power (1989) and Decay of Fiction (2002), the sketch- based experimentation of his earlier work is supplanted with a symphonic form that seeks to unify its disparate elements into a thematically cohesive whole, often with more pronounced political engagement. In both phases of his career, O’Neill has used the optical printer to experiment with form, which is often linked to art historical ideas about design, process, and perspective. This stands in contrast to Barbara Hammer, whose own innovative use of the printer is tied directly to its capacity to provide an emotionally accurate representation of her personal feelings and desires. ! Barbara Hammer: The Technology of Touch If ever there were a meta-film about optical printing, materiality, and the marginalization of the avant-garde filmmaker, Barbara Hammer’s Endangered (1988) is it. An urgent warning about the precarious position of experimental filmmakers, light, and life on planet Earth, this fragile film begins with an off-kilter double exposure of Hammer working steadily on her optical printer while snowflakes, depicted as particles of light energy, swirl around her silhouette. In a series of traveling mattes, boxes-within-boxes expand and contract, dividing abstract patterns of light into discontinuous fragments. -

1: for Me, It Was Personal Names with Too Many of the Letter "Q"

1: For me, it was personal names with too many of the letter "q", "z", or "x". With apostrophes. Big indicator of "call a rabbit a smeerp"; and generally, a given name turns up on page 1... 2: Large scale conspiracies over large time scales that remain secret and don't fall apart. (This is not *explicitly* limited to SF, but appears more often in branded-cyberpunk than one would hope for a subgenre borne out of Bruce Sterling being politically realistic in a zine.) Pretty much *any* form of large-scale space travel. Low earth orbit, not so much; but, human beings in tin cans going to other planets within the solar system is an expensive multi-year endevour that is unlikely to be done on a more regular basis than people went back and forth between Europe and the americas prior to steam ships. Forget about interstellar travel. Any variation on the old chestnut of "robots/ais can't be emotional/creative". On the one hand, this is realistic because human beings have a tendency for othering other races with beliefs and assumptions that don't hold up to any kind of scrutiny (see, for instance, the relatively common belief in pre-1850 US that black people literally couldn't feel pain). On the other hand, we're nowhere near AGI right now and it's already obvious to everyone with even limited experience that AI can be creative (nothing is more creative than a PRNG) and emotional (since emotions are the least complex and most mechanical part of human experience and thus are easy to simulate). -

1907 Journal of General Convention

Journal of the General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America 1907 Digital Copyright Notice Copyright 2017. The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America / The Archives of the Episcopal Church All rights reserved. Limited reproduction of excerpts of this is permitted for personal research and educational activities. Systematic or multiple copy reproduction; electronic retransmission or redistribution; print or electronic duplication of any material for a fee or for commercial purposes; altering or recompiling any contents of this document for electronic re-display, and all other re-publication that does not qualify as fair use are not permitted without prior written permission. Send written requests for permission to re-publish to: Rights and Permissions Office The Archives of the Episcopal Church 606 Rathervue Place P.O. Box 2247 Austin, Texas 78768 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 512-472-6816 Fax: 512-480-0437 JOURNAL OF THE GENERAL CONVENTION OF THE -roe~tant epizopal eburib IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Held in the City of Richmond From October Second to October Nineteenth, inclusive In the Year of Our Lord 1907 WITH APPENDIcES PRINTED FOR THE CONVENTION 1907 SECRETABY OF THE HOUSE OF DEPUTIES. THE REV. HENRY ANSTICE, D.D. Office, 281 FOURTH AVE., NEW YORK. aTo whom, as Secretary of the Convention, all communications relating to the general work of the Convention should be addressed; and to whom should be forwarded copies of the Journals of Diocesan Conventions or Convocations, together with Episcopal Charges, State- ments, Pastoral Letters, and other papers which may throw light upon the state of the Church in the Diocese or Missionary District, as re- quired by Canon 47, Section II. -

St. John's Episcopal Church

THE HISTORY OF ST. JOHN'S EPISCOPAL CHURCH MONTICELLO, NEW YORK. FOR ONE HUNDRED YEARS 1816-1916 COMPILED TO COMMEMORATE ITS CENTENARY EDITED BY THE REVEREND WALTER WHITE REID -.r ...... ( / .~. ;--_ '" --_.._--_ - •. ~- . rnTl 1\';"" l' , r r: E~ .,{.~.". "".n"::}l .... l\ t ,! p T · ~ ; T ~ r ' iIr"~ 41"" I L .L.L.i V .L .:. .e ,d •..:l 4. I i f ,I I t ~._ ....... ~-------- _.... - -.--_.---_., ·,. • FIRST CHURCH 1835-1882 PREFACE tW)HE collection of data in connection with a parish history is probably a difficult problem for everyone to whom the task falls. It is to be doubted whether any parish has, in its present possession, the complete record of its history and activity since its inception. Carelessness and fire seem to be the destroying elements, whereby documents of intrinsic worth, particularly valuable to a compiler of such a work as this, have been lost forever. From the foundation of this parish in 1816 down to the year 1831, no information, other than meagre generalities, is obtain able. The vestry minutes and church records were in the pos session of the Rev. Edward K. Fowler, and were destroyed when the old Mansion House was burned. In fact no church records back of 1870 are now in existence, lost probably in the same fire. However, the gap has been imperfectly bridged by refer ences to family records, old scrap books, clippings, and Quinlan's "History ofSullivan Co~tnty." I am particularly indebted to Major John Waller, whose keen memory at the age of 90 has enabled me to clear away many doubts regarding the past, and to present to the parish this ac count of its history. -

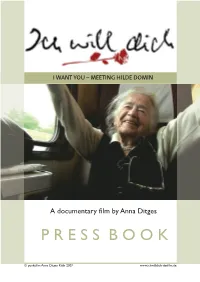

P R E S S B O

I WANT YOU – MEETING HILDE DOMIN A documentary fi lm by Anna Ditges P R E S S B O O K © punktfi lm Anna Ditges Köln 2007 www.ichwilldich-derfi lm.de I WANTBEGEGNUNGEN YOU – MEETING MIT HILDE HILDE DOMIN DOMIN CONTENTS The Film 3 Short Synopsis 4 Summary 5 Credits 8 Technical Details 9 An Interview with Anna Ditges 10 An Interview with Felix Kuballa 12 The Protagonist 14 Biography 15 Publications and Awards 16 The Director 17 Filmography 18 Contact / Impressum 19 Material Press English Subtitles CD (fi lm stills, set photography, texts) DVD (original version with English subtitles) © punktfi lm Anna Ditges Köln 2007 www.ichwilldichwww.ichwilldich-derfi lm.de 2 I WANTBEGEGNUNGEN YOU – MEETING MIT HILDE HILDE DOMIN DOMIN THE FILM “I want you - Meeting Hilde Domin” is a very personal and direct documentary fi lm about the life and work of poetess Hilde Domin: fi lm-maker Anna Ditges, almost 70 years younger than Domin, accompanied and fi lmed the Grande Dame of German post-war literature during the last two years of her long and eventful life. © punktfi lm Anna Ditges Köln 2007 www.ichwilldich-derfi lm.de 3 I WANTBEGEGNUNGEN YOU – MEETING MIT HILDE HILDE DOMIN DOMIN SHORT SYNOPSIS A young film-maker discovers Hilde Domin‘s lyric poetry and decides to get in touch with the celebrated poetess herself. She encounters a highly unconventional 95 year-old in an apartment full of books, roses and memories – with a life story that mirrors the last century. Hilde Domin, born in 1909, tells openly about her turbulent and troubled life: of her child- hood as an assimilated Jewess in Cologne, of more than two decades spent in exile, of the return to post-war Germany and her late career as a writer. -

Comics and Science Fiction in West Bengal

DANIELA CAPPELLO | 1 Comics and Science Fiction in West Bengal Daniela Cappello Abstract: In this paper I look at four examples of Bengali SF (science fiction) comics by two great authors and illustrators of sequential art: Mayukh Chaudhuri (Yātrī, Smārak) and Narayan Debnath (Ḍrāgoner thābā, Ajānā deśe). Departing from a con- ventional understanding of SF as a fixed genre, I aim at showing that the SF comic is a ‘mode’ rather than a ‘genre’, building on a very fluid notion of boundaries between narrative styles, themes, and tropes formally associated with fixed genres. In these Bengali comics, it is especially the visual space of the comic that allows for blending and ‘contamination’ with other typical features drawn from adventure and detective fiction. Moreover, a dominant thematic thread that cross-cuts the narratives here examined are the tropes of the ‘other’ and the ‘unknown’, which are in fact central images of both adventure and SF: the exploration and encounter with ‘unknown’ (ajānā) worlds and ‘strange’ species (adbhut jāti) is mirrored in the usage of a lan- guage that expresses ‘otherness’ and strangeness. These examples show that the medium of the comic framing the SF story adds further possibilities of reading ‘genre hybridity’ as constitutive of the genre of SF as such. WHAT’S IN A COMIC? Before addressing SF comics in West Bengal, I will first look at some interna- tional definitions of comic to outline the main problematics that have been raised in the literature on this subject. In one of the first books introducing the world of comics to artists and academics, Will Eisner looks at the me- chanics of ‘sequential art’ (a term coined by Eisner himself) describing it as a dual ‘form of reading’ (Eisner 1985: 8): The format of the comic book presents a montage of both word and image, and the reader is thus required to exercise both visual and verbal interpretive skills. -

Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Banerjee [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Suparno, "Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3181. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. OTHER TOMORROWS: POSTCOLONIALITY, SCIENCE FICTION AND INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Suparno Banerjee B. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2000 M. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2002 August 2010 ©Copyright 2010 Suparno Banerjee All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support of my professors, peers, friends and family. Both my supervisors, Dr. Pallavi Rastogi and Dr. Carl Freedman, guided the committee proficiently and helped me maintain a steady progress towards completion. Dr. Rastogi provided useful insights into the field of postcolonial studies, while Dr. Freedman shared his invaluable knowledge of science fiction. Without Dr. Robin Roberts I would not have become aware of the immensely powerful tradition of feminist science fiction. -

Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century Joshua J

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2016 yS mposium Apr 20th, 3:40 PM - 4:00 PM Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century Joshua J. Taylor Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Musicology Commons Taylor, Joshua J., "Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century" (2016). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 4. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2016/podium_presentations/4 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century What does it mean to be Russian? In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Russian nobility was engrossed with French culture. According to Dr. Marina Soraka and Dr. Charles Ruud, “Russian nobility [had a] weakness for the fruits of French civilization.”1 When Peter the Great came into power in 1682-1725, he forced Western ideals and culture into the very way of life of the aristocracy. “He wanted to Westernize and modernize all of the Russian government, society, life, and culture… .Countries of the West served as the emperor’s model; but the Russian ruler also tried to adapt a variety of Western institutions to Russian needs and possibilities.”2 However, when Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Russia in 1812, he threw the pro- French aristocracy in Russia into an identity crisis.