HOMING GREEN Staifc Twersttyubrary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Concrete Scales: a Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, Guia Gali

Using Concrete Scales: A Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, Guia Gali To cite this version: Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, Guia Gali. Using Concrete Scales: A Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2013, 19 (12), pp.2426-2435. 10.1109/TVCG.2013.210. hal-00851733v1 HAL Id: hal-00851733 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-00851733v1 Submitted on 8 Jan 2014 (v1), last revised 8 Jan 2014 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Using Concrete Scales: A Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, and Guia Gali a b c Fig. 1. Illustrates popular representations of complex measures: (a) US Debt (Oto Godfrey, Demonocracy.info, 2011) explains the gravity of a 115 trillion dollar debt by progressively stacking 100 dollar bills next to familiar objects like an average-sized human, sports fields, or iconic New York city buildings [15] (b) Sugar stacks (adapted from SugarStacks.com) compares caloric counts contained in various foods and drinks using sugar cubes [32] and (c) How much water is on Earth? (Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Howard Perlman, USGS, 2010) shows the volume of oceans and rivers as spheres whose sizes can be compared to that of Earth [38]. -

Charles and Ray Eames's Powers of Ten As Memento Mori

chapter 2 Charles and Ray Eames’s Powers of Ten as Memento Mori In a pantheon of potential documentaries to discuss as memento mori, Powers of Ten (1968/1977) stands out as one of the most prominent among them. As one of the definitive works of Charles and Ray Eames’s many successes, Pow- ers reveals the Eameses as masterful designers of experiences that communi- cate compelling ideas. Perhaps unexpectedly even for many familiar with their work, one of those ideas has to do with memento mori. The film Powers of Ten: A Film Dealing with the Relative Size of Things in the Universe and the Effect of Adding Another Zero (1977) is a revised and up- dated version of an earlier film, Rough Sketch of a Proposed Film Dealing with the Powers of Ten and the Relative Size of Things in the Universe (1968). Both were made in the United States, produced by the Eames Office, and are widely available on dvd as Volume 1: Powers of Ten through the collection entitled The Films of Charles & Ray Eames, which includes several volumes and many short films and also online through the Eames Office and on YouTube (http://www . eamesoffice.com/ the-work/powers-of-ten/ accessed 27 May 2016). The 1977 version of Powers is in color and runs about nine minutes and is the primary focus for the discussion that follows.1 Ralph Caplan (1976) writes that “[Powers of Ten] is an ‘idea film’ in which the idea is so compellingly objectified as to be palpably understood in some way by almost everyone” (36). -

Urantia, a Cosmic View of the Architecture of the Universe

Pr:rt llr "Lost & First Men" vo-L-f,,,tE 2 \c 2 c6510 ADt t 4977 s1 50 Bryce Bond ot the Etherius Soeie& HowTo: ond, would vou Those Stronge believe. Animol Mutilotions: Aicin Wotts; The Urontic BookReveols: N Volume 2, Number 2 FRONTIERS April,1977 CONTENTS REGULAR FEATURES_ Editorial .............. o Transmissions .........7 Saucer Waves .........17 Astronomy Lesson ...... ........22 Audio-Visual Scanners ...... ..7g Cosmic Print-Outs . ... .. ... .... .Bz COSMIC SPOTLIGHTS- They Came From Sirjus . .. .....Marc Vito g Jack, The Animal Mutilator ........Steve Erdmann 11 The Urantia Book: Architecture of the Universe 26 rnterview wirh Alan watts...,f ro, th" otf;lszidThow ut on the Frontrers of science; rr"u" n"trno?'rnoLllffill sutherly 55 Kirrian photography of the Human Auracurt James R. Wolfe 58 UFOs and Time Travel: Doing the Cosmic Wobble John Green 62 CF SERIAL_ "Last & paft2 First Men ," . Olaf Stapledon 35 Cosmic Fronliers;;;;;;J rs DUblrshed Editor: Arthur catti bi-morrhiyy !y_g_oynby Cosm i publica- Art Director: Vincent priore I ons, lnc. at 521 Frith Av.nr."Jb.ica- | New York,i:'^[1 New ';;'].^iffiiYork 10017. I Associate Art Director: Fiank DeMarco Copyright @ 1976 by Cosmic Contributing Editors:John P!blications.l-9,1?to^ lnc, Alt ?I,^c-::Tf riohrs re- I creen, Connie serued, rncludrnqiii,jii"; i'"''1,1.",th€ irqlil ot lvlacNamee. Charles Lane, Wm. Lansinq Brown. jon T; I reproduction ,1wr-or€rn whol€ o,or Lnn oarrpa.'. tsasho Katz, A. A. Zachow, Joseph Belv-edere SLngle copy price: 91.50 I lnside Covers: Rico Fonseca THE URANTIA BOOK: lhe Cosmic view of lhe ARCHITECTURE of lhe UNIVERSE -qnd How Your Spirit Evolves byA.A Zochow Whg uos monkind creoted? The Isle of Paradise is a riers, the Creaior Sons and Does each oJ us houe o pur. -

The Dial and Transcendentalist Music Criticism” by WESLEY T

The ‘yearnings of the heart to the Infinite’: The Dial and Transcendentalist Music Criticism” by WESLEY T. MOTT “When my hoe tinkled against the stones, that music echoed to the woods and the sky . and I remembered with as much pity as pride, if I remembered at all, my acquaintances who had gone to the city to attend the oratorios.” So wrote contrary Henry Thoreau in “Walden” (1854; [Princeton UP, 1971], p. 159). His literary acquaintances, in fact, had made important contributions to the emergence of music criticism in Boston a decade earlier in the Transcendentalist periodical, the Dial. Published from 1840 to 1844 and edited by Margaret Fuller and Ralph Waldo Emerson, the Dial promised readers in the first issue to give voice to a “new spirit” and to “new views and the dreams of youth,” to aid “the progress of a revolution . united only in a common love of truth, and love of its work” (the Dial, 4 vols. [rpt. New York: Russell & Russell, 1961], 1:1-2. The definitive study is Joel Myerson, The New England Transcendentalists and the Dial: A History of the Magazine and Its Contributors [Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson UP, 1980]). Featuring poetry, essays, reviews, and translations on an eclectic range of literary, philosophical, theological, and aesthetic topics, the Dial published only four articles substantially about music: one by John Sullivan Dwight, one by John Francis Tuckerman, and two by Fuller (excluding her lengthy study Romaic and Rhine Ballads [3:137-80] and brief commentary scattered in review articles). Each wrote one installment of an annual Dial feature for 1840-42—a review of the previous winter’s concerts in Boston. -

List of New Thought Periodicals Compiled by Rev

List of New Thought Periodicals compiled by Rev. Lynne Hollander, 2003 Source Title Place Publisher How often Dates Founding Editor or Editor or notes Key to worksheet Source: A = Archives, B = Braden's book, L = Library of Congress If title is bold, the Archives holds at least one issue A Abundant Living San Diego, CA Abundant Living Foundation Monthly 1964-1988 Jack Addington A Abundant Living Prescott, AZ Delia Sellers, Ministries, Inc. Monthly 1995-2015 Delia Sellers A Act Today Johannesburg, So. Africa Association of Creative Monthly John P. Cutmore Thought A Active Creative Thought Johannesburg, So. Africa Association of Creative Bi-monthly Mrs. Rea Kotze Thought A, B Active Service London Society for Spreading the Varies Weekly in Fnded and Edited by Frank Knowledge of True Prayer 1916, monthly L. Rawson (SSKTP), Crystal Press since 1940 A, B Advanced Thought Journal Chicago, IL Advanced Thought Monthly 1916-24 Edited by W.W. Atkinson Publishing A Affirmation Texas Church of Today - Divine Bi-monthly Anne Kunath Science A, B Affirmer, The - A Pocket Sydney, N.S.W., Australia New Thought Center Monthly 1927- Miss Grace Aguilar, monthly, Magazine of Inspiration, 2/1932=Vol.5 #1 Health & Happiness A All Seeing Eye, The Los Angeles, CA Hall Publishing Monthly M.M. Saxton, Manly Palmer Hall L American New Life Holyoke, MA W.E. Towne Quarterly W.E. Towne (referenced in Nautilus 6/1914) A American Theosophist, The Wheaton, IL American Theosophist Monthly Scott Minors, absorbed by Quest A Anchors of Truth Penn Yan, NY Truth Activities Weekly 1951-1953 Charlton L. -

A Biblical View of the Cosmos the Earth Is Stationary

A BIBLICAL VIEW OF THE COSMOS THE EARTH IS STATIONARY Dr Willie Marais Click here to get your free novaPDF Lite registration key 2 A BIBLICAL VIEW OF THE COSMOS THE EARTH IS STATIONARY Publisher: Deon Roelofse Postnet Suite 132 Private Bag x504 Sinoville, 0129 E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 012-548-6639 First Print: March 2010 ISBN NR: 978-1-920290-55-9 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover design: Anneette Genis Editing: Deon & Sonja Roelofse Printing and binding by: Groep 7 Printers and Publishers CK [email protected] Click here to get your free novaPDF Lite registration key 3 A BIBLICAL VIEW OF THE COSMOS CONTENTS Acknowledgements...................................................5 Introduction ............................................................6 Recommendations..................................................14 1. The creation of heaven and earth........................17 2. Is Genesis 2 a second telling of creation? ............25 3. The length of the days of creation .......................27 4. The cause of the seasons on earth ......................32 5. The reason for the creation of heaven and earth ..34 6. Are there other solar systems?............................36 7. The shape of the earth........................................37 8. The pillars of the earth .......................................40 9. The sovereignty of the heaven over the earth .......42 10. The long day of Joshua.....................................50 11. The size of the cosmos......................................55 12. The age of the earth and of man........................59 13. Is the cosmic view of the bible correct?..............61 14. -

Vedanta in the West: Past, Present, and Future

Vedanta in the West: Past, Present, and Future Swami Chetanananda What Is Vedanta? Vedanta is the culmination of all knowledge, the sacred wisdom of the Indian sages, the sum of the transcendental experiences of the seers of Truth. It is the essence, or the conclusion, of the scriptures known as the Vedas. Because the Upanishads come at the end of the Vedas they are collectively referred to as Vedanta. Literally, Veda means "knowledge" and anta means "end." Vedanta is a vast subject. Its scriptures have been evolving for the last five thousand years. The three basic scriptures of Vedanta are the Upanishads (the revealed truths), the Brahma Sutras (the reasoned truths), and the Bhagavad Gita (the practical truths). Some Teachings from Vedanta Here are some teachings from the Upanishads: “Arise! Awake! Approach the great teachers and learn.” “Aham Brahmasmi.” [I am Brahman.] “Tawamasi.” [Thou art That.] “Sarvam khalu idam Brahma.” [Verily, everything is Brahman.] “Whatever exists in this changing universe is enveloped by God.” “If a man knows Atman here, he then aains the true goal of life.” “Om is the bow; the Atman is the arrow; Brahman is said to be the mark. It is to be struck by an undistracted mind.” “He who knows Brahman becomes Brahman.” “His hands and feet are everywhere. His eyes, heads, and mouths are everywhere. His ears are everywhere. He pervades everything in the universe.” “Speak the truth. Practise dharma. Do not neglect your study of the Vedas. Treat your mother as God. Treat your father as God. Treat your teacher as God. -

California State University, Northridge the World As

- .... -~-·· ---- -~-~-. -· --. -· ·------ - -~- -----~-·--~-~-*-·----~----~----·····"'·-.-·-~·-·--·---~---- ---~-··i ' CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE THE WORLD AS ILLUSION \\ EMERSON'S AMERICANIZATION ·oF MAYA A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English by Rose Marian Shade [. I I May, 1975 The thesis of Rose Marian Shade 1s approved: California State University, Northridge May, 1975 ii _,---- ~---'"·--------------- -------- -~-------- ---·· .... -· - ... ------------ ---······. -·- -·-----··- ··- --------------------·--···---··-·-··---- ------------------------: CONTENTS Contents iii Abstract iv Chapter I THE BACKGROUND 1 II INDIAN FASCINATION--HARVARD DAYS 5 III ONE OF THE WORLD'S OLDEST RELIGIONS 12 IV THE EDUCATION OF AN ORIENTALIST 20 v THE USES OF ILLUSION 25 Essays Nature 25 History 28 The Over-Soul 29 Experience 30 Plato 32 Fate 37 Illusions 40 Works and Days 47 Poems Hamatreya 49 Brahma 54 Maia 59 VI THE WORLD AS ILLUSION: YANKEE STYLE 60 VII ILLUSION AS A WAY OF LIFE 63 NOTES 70 BIBLIOGRAPHY 77 iii I I ABSTRACT THE WORLD AS ILLUSION EMERSON'S AMERICANIZATION OF MAYA by Rose Marian Shade Master of Arts in English May, 1975 One of the most important concepts that Ralph Waldo Emerson passed on to America's new philosophies and religions was borrowed from one of the world's oldest systems of thought--Hinduism. This was the Oriental view of the phenomenal world as Maya or Illusion concealing the unity of Brahman under a variety of names and forms. This thesis describes Emerson's introduction to Hindu thought and literature during his college days, reviews the_concept of Maya found in Hindu scriptures, and details Emerson's deepened interest and wide reading in Hindu philosophy in later life. -

P. Vasundhara Rao.Cdr

ORIGINAL ARTICLE ISSN:-2231-5063 Golden Research Thoughts P. Vasundhara Rao Abstract:- Literature reflects the thinking and beliefs of the concerned folk. Some German writers came in contact with Ancient Indian Literature. They were influenced by the Indian Philosophy, especially, Buddhism. German Philosopher Arther Schopenhauer, was very much influenced by the Philosophy of Buddhism. He made the ancient Indian Literature accessible to the German people. Many other authors and philosophers were influenced by Schopenhauer. The famous German Indologist, Friedrich Max Muller has also done a great work, as far as the contact between India and Germany is concerned. He has translated “Sacred Books of the East”. INDIAN PHILOSOPHY IN GERMAN WRITINGS Some other German authors were also influenced by Indian Philosophy, the traces of which can be found in their writings. Paul Deussen was a great scholar of Sanskrit. He wrote “Allgemeine Geschichte der Philosophie (General History of the Philosophy). Friedrich Nieztsche studied works of Schopenhauer in detail. He is one of the first existentialist Philosophers. Karl Eugen Neuman was the first who translated texts from Pali into German. Hermann Hesse was also influenced by Buddhism. His famous novel Siddhartha is set in India. It is about the spiritual journey of a man (Siddhartha) during the time of Gautam Buddha. Indology is today a subject in 13 Universities in Germany. Keywords: Indian Philosophy, Germany, Indology, translation, Buddhism, Upanishads.specialization. www.aygrt.isrj.org INDIAN PHILOSOPHY IN GERMAN WRITINGS INTRODUCTION Learning a new language opens the doors of a different culture, of the philosophy and thinking of that particular society. How true it is in case of Indian philosophy having traveled to Germany years ago. -

"Das Tier, Das Dujetzttötest, Bist Du Selbst Arthurschopenhauer Und

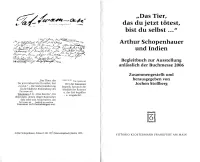

"Das Tier, das du jetzt tötest, bist du selbst Arthur Schopenhauer 4 und Indien Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung anlässlich der Buchmesse 2006 Zusammengestellt und "Das Thier, das Carica p 80 Tat-twam-asi herausgegeben von Du jetzt tödtest bist Du selbst, bist Wer das Tatgumes es - Jochen Stollberg jetzt." Die Seelenwanderung begreift, hat auch die ist die bildliche Einkleidung des Idealität des Raumes (Tat twam asi) u. der Zeit begriffen Tatoumes d. h. "Dies bist Du", für - u. umgekehrt. diejenigen, denen obiger Kantischer Satz oder sein Aequivalent, das Tat twam asi fasslich zu machen Tatoumes nicht beizubringen war. Arthur Schopenhauer, Foliant 2, Bi. 193r [Manuskriptbuchl Berlin 1826 VITTORIO KLOSTERMANN FRANKFURT AM MAIN Inhalt Klaus Ring Zum Geleit Matthias Koßler Grußwort Jochen Stollberg Arthur Schopenhauers Annäherung an die indische Welt 5 Urs App OUM - das erste Wort von Schopenhauers Lieblingsbuch 37 Urs App NICHTS - das letzte Wort von Schopenhauers Hauptwerk 51 Douglas L. Berger Erbschaften einer philosophischen Begegnung 61 Stephan Atzert Nirvana und Maya bei Schopenhauer 79 Heiner Feldhoff Und dann und wann ein weiser Elefant - Über Paul Deussens "Erinnerungen Indien" 85 Michael Gerhard Paul Deussen - Eine deutsch-indische Geistesbeziehung 101 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Arati Barua verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek of in India - Deutschen detaillierte bibliographische Daten Re-discovery Schopenhauer Nationalbibliographie; of the work and of sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Founding membership Indian branch of Schopenhauer Society 119 Thomas Frankfurter Bibliotheksschriften Regehly Schopenhauer und Siddharta 135 Herausgegeben von der Gesellschaft der Freunde der Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek Frankfurt am Main e. -

Journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson 1820-1872

lil p lip m mi: Ealpi) ^alUa emeraum* COMPLETE WORKS. Centenary EdittOH. 12 vols., crown 8vo. With Portraits, and copious notes by Ed- ward Waldo Emerson. Price per volume, $1.75. 1. Nature, Addresses, and Lectures. 3. Essays : First Series. 3. Essays : Second Series. 4. Representative Men. 5. English Traits. 6. Conduct of Life. 7. Society and Solitude. 8. Letters and Social Aims. 9. Poems, xo. Lectures and Biographical Sketches, 11. Miscellanies. 13. Natural History of Intellect, and other Papers. With a General Index to Emerson's Collected Works. Riverside Edition. With 2 Portraits. la vols., each, i2mo. gilt top, $1.75; the set, $31.00. Little Classic Edition. 13 vols. , in arrangement and coo- tents identical with Riverside Edition, except that vol. la is without index. Each, i8mo, $1.25 ; the set, $15 00. POEMS. Household Edition. With Portrait. lamo, $1.50} full gilt, $2.00. ESSAYS. First and Second Series. In Cambridge Classics. Crown 8vo, $1.00. NATURE, LECTURES, AND ADDRESSES, together with REPRESENTATIVE MEN. In Cambridge Classics. Crown 8vo, f i.oo. PARNASSUS. A collection of Poetry edited by Mr. Emer- son., Introductory Essay. Hoitsekold Edition. i2mo, 1^1.50, Holiday Edition. Svo, $3.00. EMERSON BIRTHDAY BOOK. With Portrait and Illus- trations. i8mo, $1.00. EMERSON CALENDAR BOOK. 32mo, parchment-paper, 35 cents. CORRESPONDENCE OF CARLYLE AND EMERSON. 834-1872. Edited by Charles Eliot Norton. 2 ols. crown Svo, gilt top, $4.00. Library Edition. 2 vols. i2mo, gilt top, S3.00. CORRESPONDENCE OF JOHN STERLING AND EMER- SON. Edited, with a sketch of Sterling's life, by Ed- ward Waldo Emerson. -

Wilderness and the Passing Show

Wildness and the Passing Show / 81 To answer these questions, though, we turn, first, to the Tran- I 3 1 Wildness and the Passing Show scendentalist gospel that reflected and, in some measure, shaped TRANSCENDENTAL RELIGION AND ITS LEGACIES the popular mentality. Standing at the intersection of elite and popular worlds, Transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau at once absorbed and created religious "A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds," wrote insight, giving ideas compelling shape and extended currency the still-youthful Ralph Waldo Emerson.' If so, he had already through their language. Emerson, especially, in his lectures to practiced what he preached, for some five years previously Emer- lyceum audiences faithfully proclaimed his new views, and du- son's book Nature had announced the virtues of inconsistency by tiful newspaper reporters summarized for those unable to attend embodying them. In this, the gospel of Transcendentalism, its lyceum gatherings. "In the decade of 1850-1860," Perry Miller leader ~roclaimeda message that inspired with its general prin- wrote, "he achieved a kind of apothe~sis,"~-an apotheosis, we ciples but, with the opaqueness of its rhetoric, mostly discouraged may add, that continued to endure. Thoreau, the "sleeper," did not analytic scrutiny. Yet Emerson's Nature was to have a profound engage in lyceum activity to nearly the degree that Emerson did. effect on many, even outside Transcendentalist circles. Still But in his writings he became a prophet to a later generation of more, Nature was to reflect and express patterns of thinking and seekers. Together the two and their disciples handed on an ambigu- feeling that found flesh in two seemingly disparate nineteenth- ous heritage, bringing the Emersonian inconsistency into service century movements-that of wilderness preservation and that of to obscure a crack in the religious cosmos.