New York Non-Native Plant Invasiveness Ranking Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report

Final Report Final pre-release investigations of the gorse thrips (Sericothrips staphylinus) as a biocontrol agent for gorse (Ulex europaeus) in North America Date: August 31, 2012 Award Number: 10-CA-11420004-184 Report Period: June 1, 2010– May 31, 2012 Project Period: June 1, 2010– May 31, 2012 Recipient: Oregon State University Recipient Contact Person: Fritzi Grevstad Principal Investigator/ Project Director: Fritzi Grevstad Introduction Gorse (Ulex europaeus) is an environmental weed classified as noxious in the states of Washington, Oregon, California, and Hawaii. A classical biological control program has been applied in Hawaii with the introduction of 4 gorse-feeding arthropods, but only two of these (a mite and a seed weevil) have been introduced to the mainland U.S. The two insects that have not yet been introduced include the gorse thrips, Sericothips staphylinus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), and the moth Agonopterix umbellana (Lepidoptera: Oecophoridae). With prior support from the U.S. Forest Service (joint venture agreement # 07-JV-281), we were able to complete host specificity testing of S. staphylinus on 44 North American plant species that were on the original test plant list. However, following review of the proposed Test Plant List, the Technical Advisory Group on Biocontrol of Weeds (TAG) recommended that we include an additional 18 plant species for testing. In this report, we present host specificity testing and related objectives necessary to bring the program to the implementation stage. Objectives (1) Acquire and grow the additional 18 species of plants recommended by the TAG. (2) Complete host specificity trials for the gorse thrips on the 18 plant species. -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

CHLOROPLAST Matk GENE PHYLOGENY of SOME IMPORTANT SPECIES of PLANTS

AKDENİZ ÜNİVERSİTESİ ZİRAAT FAKÜLTESİ DERGİSİ, 2005, 18(2), 157-162 CHLOROPLAST matK GENE PHYLOGENY OF SOME IMPORTANT SPECIES OF PLANTS Ayşe Gül İNCE1 Mehmet KARACA2 A. Naci ONUS1 Mehmet BİLGEN2 1Akdeniz University Faculty of Agriculture Department of Horticulture, 07059 Antalya, Turkey 2Akdeniz University Faculty of Agriculture Department of Field Crops, 07059 Antalya, Turkey Correspondence addressed E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In this study using the chloroplast matK DNA sequence, a chloroplast-encoded locus that has been shown to be much more variable than many other genes, from one hundred and forty two plant species belong to the families of 26 plants we conducted a study to contribute to the understanding of major evolutionary relationships among the studied plant orders, families genus and species (clades) and discussed the utilization of matK for molecular phylogeny. Determined genetic relationship between the species or genera is very valuable for genetic improvement studies. The chloroplast matK gene sequences ranging from 730 to 1545 nucleotides were downloaded from the GenBank database. These DNA sequences were aligned using Clustal W program. We employed the maximum parsimony method for phylogenetic reconstruction using PAUP* program. Trees resulting from the parsimony analyses were similar to those generated earlier using single or multiple gene analyses, but our analyses resulted in strict consensus tree providing much better resolution of relationships among major clades. We found that gymnosperms (Pinus thunbergii, Pinus attenuata and Ginko biloba) were different from the monocotyledons and dicotyledons. We showed that Cynodon dactylon, Panicum capilare, Zea mays and Saccharum officiarum (all are in the C4 metabolism) were improved from a common ancestors while the other cereals Triticum Avena, Hordeum, Oryza and Phalaris were evolved from another or similar ancestors. -

Producción De Forraje Y Competencia Interespecífica Del Cultivo Asociado De Avena (Avena Sativa) Con Vicia (Vicia Sativa) En Condiciones De Secano Y Gran Altitud

Rev Inv Vet Perú 2018; 29(4): 1237-1248 http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rivep.v29i4.15202 Producción de forraje y competencia interespecífica del cultivo asociado de avena (Avena sativa) con vicia (Vicia sativa) en condiciones de secano y gran altitud Forage production and interspecific competition of oats (Avena sativa) and common vetch (Vicia sativa) association under dry land and high-altitude conditions Francisco Espinoza-Montes1,2,4, Wilfredo Nuñez-Rojas1, Iraida Ortiz-Guizado3, David Choque-Quispe2 RESUMEN Se experimentó el cultivo asociado de avena (Avena sativa) y vicia común (Vicia sativa) en condiciones de secano, a 4035 m sobre el nivel del mar, para conocer su comportamiento y efectos en el rendimiento, calidad de forraje y competencia interespecífica. En promedio, el rendimiento de forraje verde, materia seca y calidad de forraje fueron superiores al del monocultivo de avena (p<0.05). El porcentaje de proteína cruda se incrementó en la medida que creció la proporción de vicia común en la asocia- ción, acompañado de una disminución del contenido de fibra. En cuanto a los índices de competencia, el cultivo asociado de avena con vicia favorece el rendimiento relativo total de forraje (LERtotal>1). Ninguna de las especies manifestó comportamiento agresivo (A=0). Se observó mayor capacidad competitiva de la vicia común (CR>1) comparado con la capacidad competitiva de la avena. Palabras clave: cultivo asociado; rendimiento; calidad de forraje; competencia interespecífica ABSTRACT The oats (Avena sativa) and common vetch (Vicia sativa) cultivated in association was evaluated under dry land conditions at 4035 m above sea level to determine its performance and effects on yield, forage quality and interspecific competition. -

Vascular Plants at Fort Ross State Historic Park

19005 Coast Highway One, Jenner, CA 95450 ■ 707.847.3437 ■ [email protected] ■ www.fortross.org Title: Vascular Plants at Fort Ross State Historic Park Author(s): Dorothy Scherer Published by: California Native Plant Society i Source: Fort Ross Conservancy Library URL: www.fortross.org Fort Ross Conservancy (FRC) asks that you acknowledge FRC as the source of the content; if you use material from FRC online, we request that you link directly to the URL provided. If you use the content offline, we ask that you credit the source as follows: “Courtesy of Fort Ross Conservancy, www.fortross.org.” Fort Ross Conservancy, a 501(c)(3) and California State Park cooperating association, connects people to the history and beauty of Fort Ross and Salt Point State Parks. © Fort Ross Conservancy, 19005 Coast Highway One, Jenner, CA 95450, 707-847-3437 .~ ) VASCULAR PLANTS of FORT ROSS STATE HISTORIC PARK SONOMA COUNTY A PLANT COMMUNITIES PROJECT DOROTHY KING YOUNG CHAPTER CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY DOROTHY SCHERER, CHAIRPERSON DECEMBER 30, 1999 ) Vascular Plants of Fort Ross State Historic Park August 18, 2000 Family Botanical Name Common Name Plant Habitat Listed/ Community Comments Ferns & Fern Allies: Azollaceae/Mosquito Fern Azo/la filiculoides Mosquito Fern wp Blechnaceae/Deer Fern Blechnum spicant Deer Fern RV mp,sp Woodwardia fimbriata Giant Chain Fern RV wp Oennstaedtiaceae/Bracken Fern Pleridium aquilinum var. pubescens Bracken, Brake CG,CC,CF mh T Oryopteridaceae/Wood Fern Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosorum Western lady Fern RV sp,wp Dryopteris arguta Coastal Wood Fern OS op,st Dryopteris expansa Spreading Wood Fern RV sp,wp Polystichum munitum Western Sword Fern CF mh,mp Equisetaceae/Horsetail Equisetum arvense Common Horsetail RV ds,mp Equisetum hyemale ssp.affine Common Scouring Rush RV mp,sg Equisetum laevigatum Smooth Scouring Rush mp,sg Equisetum telmateia ssp. -

Davis Expedition Fund Report on Expedition / Project

DAVIS EXPEDITION FUND REPORT ON EXPEDITION / PROJECT Expedition/Project Title: Biogeography and Systematics of South American Vicia (Leguminosae) Travel Dates: 28/09/2010 – 12/11/2010 Location: Northern Chile and northern Argentina Group Members: Paulina Hechenleitner Collection of research material of Vicia in the form of Aims: herbarium specimens, habitat data, digital images, silica- dried leaf samples, and base-line data on the IUCN conservation status of Vicia. Outcome (not less than 300 words):- See attached report. Report for the Davis Expedition Fund Biogeography and Systematics of South American Vicia (Leguminosae) Botanical fieldwork to northern Chile and northern Argentina 28th of Sep to 12th of November 2010 Paulina Hechenleitner January 2011 Introduction Vicia is one of five genera in tribe Fabeae, and contains some of humanity's oldest crop plants, and is thus of great economic importance. The genus contains around 160 spp. (Lewis et al. 2005) distributed throughout temperate regions of the northern hemisphere and in temperate S America. Its main centre of diversity is the Mediterranean with smaller centres in North and South America (Kupicha, 1976). The South American species are least known taxonomically. Vicia, together with Lathyrus and a number of other temperate plant genera share an anti- tropical disjunct distribution. This biogeographical pattern is intriguing (Raven, 1963): were the tropics bridged by long distance dispersal between the temperate regions of the hemispheres, or were once continuous distributions through the tropics severed in a vicariance event? Do the similar patterns seen in other genera reflect similar scenarios or does the anti-tropical distribution arise in many different ways? The parallels in distribution, species numbers and ecology between Lathyrus and Vicia are particularly striking. -

1. Introduction

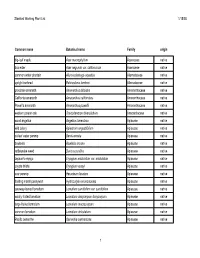

SOUTHERN JUNE 2018 VETCH SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION KEY POINTS | WHAT IS VETCH? | WHY GROW VETCH? | SUITABLE ENVIRONMENTS | MARKETS SOUTHERN GROWNOTES JUNE 2018 SECTION 1 VETCH Introduction Key points • Vetch is a versatile, high-production, low-input crop • It can be used for grazing, forage, green or brown manure, grain for livestock or for seed • It is more tolerant of acidic soils than most grain legumes, except lupin • It brings many benefits to cropping and mixed-farming rotation, including nitrogen fixation and control options for resistant weeds INTRODUCTION 1 SOUTHERN GROWNOTES JUNE 2018 SECTION 1 VETCH IN FOCUS Versatile vetch Unlike other grain crops grown in Australia, vetch is not grown for human consumption. Grain from some species is used for animal feed. The other reasons for growing vetch are to produce seed that can be sown for green manure crops, which fix nitrogen and provide a control option for weeds, or for the production of grazed and conserved forage. Determining why vetch is being grown is an important starting point in the selection and management of vetch crops. 1.1 What is vetch? Vetch (Vicia species (sp.)) is a winter-growing, multi-purpose, annual legume. It produces a scrambling vine, climbing by means of branched tendrils, which can grow as a dense pure stand to about 80 cm, or will trellis on cereals or canola with which it can be grazed, ensiled or conserved as hay. Vicia sp. is a genus of about 140 species of flowering plants commonly known as vetches. Bitter vetch (Vicia ervilia) was one of the first crops grown in the Middle East, about 9,500 years ago. -

The Genus Bruchus Was Restricted by Schilsky (6

THE HAIRY-VETCH BRUCHID, BRUCHUS BRACHIALIS FAHRAEUS, IN THE UNITED STATES ' By J. C. BRIDWELL, formerly Specialist in Bruchidae and Their Parasites, Division of Stored Product Insects^ Bureau of Entomology, and L. J. BOTTIMER, Assistant Entomologist^ Food and Drug Administration, United States Department of Agriculture INTRODUCTION The genus Bruchus was restricted by Schilsky (6) ^ to include only the immediate allies of Bruchus pisorum (L.), the pea weevil, of which he tabulated 24 species knowQ to him. To these may be added others doubtfully distinct, imperfectly known, or more recently described, which increase the nominal species of the genus to a total of about 46. All these species are native to the Palearctic region. Two of them are already well known in the United States as major pests of the plants affected. B. pisorum was the first of the genus and one of the first species of the family to be recognized. It was described in 1752, and was recorded as having destroyed in the 1740's the flourishing colonial American industry of producing dry peas for ships' stores. B. ruß- manus Boheman, the broadbean weevil, has now practically destroyed the broadbean industry of Caüfornia. A third species, B, hrachialis Fahraeus, has in recent years gained a foothold in this country, for in 1931 the junior author found it heavily infesting the seeds of vetches growing in New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and North Carolina, and in 1932 it was found in Virginia. In view of these facts it seems wise to present a brief summary of the knowledge at present available of the habits of the members of this genus and to point out the increased danger of their estabhshment in the United States as a result of changed commercial conditions. -

Atlas of the Flora of New England: Fabaceae

Angelo, R. and D.E. Boufford. 2013. Atlas of the flora of New England: Fabaceae. Phytoneuron 2013-2: 1–15 + map pages 1– 21. Published 9 January 2013. ISSN 2153 733X ATLAS OF THE FLORA OF NEW ENGLAND: FABACEAE RAY ANGELO1 and DAVID E. BOUFFORD2 Harvard University Herbaria 22 Divinity Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138-2020 [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Dot maps are provided to depict the distribution at the county level of the taxa of Magnoliophyta: Fabaceae growing outside of cultivation in the six New England states of the northeastern United States. The maps treat 172 taxa (species, subspecies, varieties, and hybrids, but not forms) based primarily on specimens in the major herbaria of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, with most data derived from the holdings of the New England Botanical Club Herbarium (NEBC). Brief synonymy (to account for names used in standard manuals and floras for the area and on herbarium specimens), habitat, chromosome information, and common names are also provided. KEY WORDS: flora, New England, atlas, distribution, Fabaceae This article is the eleventh in a series (Angelo & Boufford 1996, 1998, 2000, 2007, 2010, 2011a, 2011b, 2012a, 2012b, 2012c) that presents the distributions of the vascular flora of New England in the form of dot distribution maps at the county level (Figure 1). Seven more articles are planned. The atlas is posted on the internet at http://neatlas.org, where it will be updated as new information becomes available. This project encompasses all vascular plants (lycophytes, pteridophytes and spermatophytes) at the rank of species, subspecies, and variety growing independent of cultivation in the six New England states. -

Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 9-17-2018 Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park" (2018). Botanical Studies. 85. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/85 This Flora of Northwest California-Checklists of Local Sites is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE REDWOOD NATIONAL & STATE PARKS James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State Univerity Arcata, California 14 September 2018 The Redwood National and State Parks are located in Del Norte and Humboldt counties in coastal northwestern California. The national park was F E R N S established in 1968. In 1994, a cooperative agreement with the California Department of Parks and Recreation added Del Norte Coast, Prairie Creek, Athyriaceae – Lady Fern Family and Jedediah Smith Redwoods state parks to form a single administrative Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosporum • northwestern lady fern unit. Together they comprise about 133,000 acres (540 km2), including 37 miles of coast line. Almost half of the remaining old growth redwood forests Blechnaceae – Deer Fern Family are protected in these four parks. -

Plant List for Web Page

Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 Common name Botanical name Family origin big-leaf maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae native box elder Acer negundo var. californicum Aceraceae native common water plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae native upright burhead Echinodorus berteroi Alismataceae native prostrate amaranth Amaranthus blitoides Amaranthaceae native California amaranth Amaranthus californicus Amaranthaceae native Powell's amaranth Amaranthus powellii Amaranthaceae native western poison oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Anacardiaceae native wood angelica Angelica tomentosa Apiaceae native wild celery Apiastrum angustifolium Apiaceae native cutleaf water parsnip Berula erecta Apiaceae native bowlesia Bowlesia incana Apiaceae native rattlesnake weed Daucus pusillus Apiaceae native Jepson's eryngo Eryngium aristulatum var. aristulatum Apiaceae native coyote thistle Eryngium vaseyi Apiaceae native cow parsnip Heracleum lanatum Apiaceae native floating marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Apiaceae native caraway-leaved lomatium Lomatium caruifolium var. caruifolium Apiaceae native woolly-fruited lomatium Lomatium dasycarpum dasycarpum Apiaceae native large-fruited lomatium Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae native common lomatium Lomatium utriculatum Apiaceae native Pacific oenanthe Oenanthe sarmentosa Apiaceae native 1 Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 wood sweet cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae native mountain sweet cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Apiaceae native Gairdner's yampah (List 4) Perideridia gairdneri gairdneri Apiaceae -

Overview of Vicia (Fabaceae) of Mexico

24 LUNDELLIA DECEMBER, 2014 OVERVIEW OF VICIA (FABACEAE) OF MEXICO Billie L. Turner Plant Resources Center, The University of Texas, 110 Inner Campus Drive, Stop F0404, Austin TX 78712-1711 [email protected] Abstract: Vicia has 12 species in Mexico; 4 of the 12 are introduced. Two new names are proposed: Vicia mullerana B.L. Turner, nom. & stat. nov., (based on V. americana subsp. mexicana C.R. Gunn, non V. mexicana Hemsl.), and V. ludoviciana var. occidentalis (Shinners) B.L. Turner, based on V. occidentalis Shinners, comb. nov. Vicia pulchella Kunth subsp. mexicana (Hemsley) C.R. Gunn is better treated as V. sessei G. Don, the earliest name at the specific level. A key to the taxa is provided along with comments upon species relationships, and maps showing distributions. Keywords: Vicia, V. americana, V. ludoviciana, V. pulchella, V. sessei, Mexico. Vicia, with about 140 species, is widely (1979) provided an exceptional treatment distributed in temperate regions of both of the Mexican taxa, nearly all of which were hemispheres (Kupicha, 1982). Some of the illustrated by full-page line sketches. As species are important silage, pasture, and treated by Gunn, eight species are native to green-manure legumes. Introduced species Mexico and four are introduced. I largely such as V. faba, V. hirsuta, V. villosa, and follow Gunn’s treatment, but a few of his V. sativa are grown as winter annuals in subspecies have been elevated to specific Mexico, but are rarely collected. Gunn rank, or else treated as varieties. KEY TO THE SPECIES OF VICIA IN MEXICO (largely adapted from Gunn, 1979) 1.