From Periphery to Centre: Exploring Gendered Narratives in Select Fictions of Suchitra Bhattacharya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kiriti Omnibus 6 Pdf Free Download KIRITI OMNIBUS 4 PDF

kiriti omnibus 6 pdf free download KIRITI OMNIBUS 4 PDF. 4 (Bengali) Books- Buy Kiriti Omnibus Vol. 4 (Bengali) Books online at lowest price with Rating & Reviews, Free Shipping*, COD. – Kiriti Omnibus (Volume 4) by Niharranjan Gupta from Only Genuine Products. 30 Day Replacement Guarantee. Free Shipping. Cash On Delivery!. 4. Kiriti Omnibus (Volume 1). ☆. 46 Ratings&1 Reviews. ₹ 2% off. Language: Bengali; Binding: Hardcover; Publisher: Mitra & Ghosh Publishers Pvt. Ltd. Author: Shaktiran Akishura Country: Iraq Language: English (Spanish) Genre: Software Published (Last): 4 July 2004 Pages: 152 PDF File Size: 14.34 Mb ePub File Size: 16.27 Mb ISBN: 956-8-33772-930-1 Downloads: 5359 Price: Free* [ *Free Regsitration Required ] Uploader: Yohn. Always a class apart, Kiriti is a deadly combination of intelligence and physical power. Other Books By Kiritu. Learn more about the different existing integrations and their benefits. His curled hair is mostly combed back, and the black celluloid spectacles make his clean-shaven face highly attractive. They were posh and equally well-dressed. Niharranjan Gupta Books. Please enter your User Name, email ID and a password to register. Submit Review Submit Review. The radio adaptations of Kiriti are kirihi in the form of Sunday Suspense stories over the last few years. He is perhaps the only Bengali detective who deconstructs a crime. Kiriti Roy brings in a sense of suave and scientific rationality to the job. Here is the ultimate site for reading and downloading bangla ebooks for free. With a long coat and cap, and a Omnibux pipe hanging from his lips, he is a dashing detective and very different from other sleuths. -

Balika Badhu: a Selected Anthology of Bengali Short Stories' Monish Ranjan Chatterjee University of Dayton, [email protected]

University of Dayton eCommons Electrical and Computer Engineering Faculty Department of Electrical and Computer Publications Engineering 2002 Translation of 'Balika Badhu: A Selected Anthology of Bengali Short Stories' Monish Ranjan Chatterjee University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/ece_fac_pub Part of the Computer Engineering Commons, Electrical and Electronics Commons, Electromagnetics and Photonics Commons, Optics Commons, Other Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons, and the Systems and Communications Commons eCommons Citation Chatterjee, Monish Ranjan, "Translation of 'Balika Badhu: A Selected Anthology of Bengali Short Stories'" (2002). Electrical and Computer Engineering Faculty Publications. Paper 362. http://ecommons.udayton.edu/ece_fac_pub/362 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electrical and Computer Engineering Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Translator'sl?rcfacc This project, which began with the desire to render into English a rather long tale by Bimal Kar about five years ago, eventually grew into a considerably more extended compilation of Bengali short stories by ten of the most well known practitioners of that art since the heyday of Rabindranath Tagore. The collection is limited in many ways, not the least of which being that no woman writer has been included, and that it contains only a baker's dozen stories (if we count Bonophool's micro-stories collectively as one )-a number pitifully small considering the vast and prolific field of authors and stories a translator has at his or her disposal. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

Bangla Rohosso Golpo Pdf Free Download

Bangla Rohosso Golpo Pdf Free Download 1 / 3 Bangla Rohosso Golpo Pdf Free Download 2 / 3 Read Online Golpo in bengali pdf: http://gqj.cloudz.pw/read?file=golpo+in+bengali+pdf. bangla rohosso golpo pdf free download. bangla golpo .... Kakababu Ulka Rohosso by Sunil Gangopadhyay ... pdf, free download bangla islamic book, pdf bengali story books free, download bengali ... bangla boi , bangla golpo bangla books download, boimela books free download.. Shatabarsher Sera Rahasya Upanyas by Various Authors edited by Anish Deb Google Drive, ... Atharva Veda, Yoga Books, Free Pdf Books, Ebook Pdf, Book Collection, ... devi books pdf, mahasweta devi draupadi, mahasweta devi books free download ... Har Kapano Bhuter Golpo pdf by Various Authors, Bengali e-Books .... Categories: Bangla eBooks, eBooks, Syed Mustafa Siraj Tags: Tags: allfreebd, allfreebd ebooks, bangla epub, bangla pdf, best free bangla ebooks download, .... Bangla Rohosso Golpo Pdf Free Download >>> http://urllio.com/y4m0z c1bf6049bf 3 Nov 2015 . Free Bengali novel PDF Download now .... Bangla free pdf ebook download, Various Bengali authors novels, Rachana samagra, ... 25Ti Sera Rahasya by Sunil Gangopadhyay Bangla rohosso golpo pdf.. Tin Shatabdir Sera Bhoot Bengali Free PDF Download Horror Books, Horror Stories, Free ... Rahasya Goyenda Omnibus by Chiranjib Sen Ebook Pdf, Google Drive, ... Anondo Mela Golpo Sonkolon - আনন্দমেলা গল্পসংকলন -১, বাংলা ম্যাগাজিন .... All have the best Bengali novels book collection. Free download or read online Bangla Novel Books. In Bengali Uponnas means Novel.. Dolna- Rohosso Romancho Goyenda Bangla ebook pdf ebook name- Dolna- ... Tin Mitin by Suchitra Bhattacharya- Bengali goyenda Golpo pdf file ebook name- ... Aprakrita Krishna Prasad- Bengali cookbook pdf free download ebook name- ... -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana). -

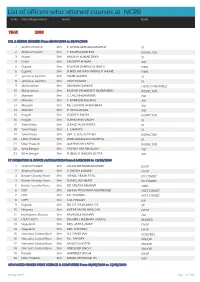

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

Family, School and Nation

Family, School and Nation This book recovers the voice of child protagonists across children’s and adult literature in Bengali. It scans literary representations of aberrant child- hood as mediated by the institutions of family and school and the project of nation-building in India in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The author discusses ideals of childhood demeanour; locates dissident children who legitimately champion, demand and fight for their rights; examines the child protagonist’s confrontations with parents at home, with teachers at school and their running away from home and school; and inves- tigates the child protagonist’s involvement in social and national causes. Using a comparative framework, the work effectively showcases the child’s growing refusal to comply as a legacy and an innovative departure from analogous portrayals in English literature. It further reviews how such childhood rebellion gets contained and re-assimilated within a predomi- nantly cautious, middle-class, adult worldview. This book will deeply interest researchers and scholars of literature, espe- cially Bengali literature of the renaissance, modern Indian history, cultural studies and sociology. Nivedita Sen is Associate Professor of English literature at Hans Raj College, University of Delhi. Her translated works (from Bengali to English) include Rabindranath Tagore’s Ghare Baire ( The Home and the World , 2004) and ‘Madhyabartini’ (‘The In-between Woman’) in The Essential Tagore (ed. Fakrul Alam and Radha Chakravarty, 2011); Syed Mustafa Siraj’s The Colo- nel Investigates (2004) and Die, Said the Tree and Other Stories (2012); and Tong Ling Express: A Selection of Bangla Stories for Children (2010). She has jointly compiled and edited (with an introduction) Mahasweta Devi: An Anthology of Recent Criticism (2008). -

Estate Directorate

ESTATE DIRECTORATE GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL New Secretariat Building, 9th Floor List of Applicants 18/03/14 Name of Estate 60-67 B.T.ROAD Estate Type M.I.G SL Application No Name of Applicant Father/Husband's name Remarks NO Date Occupation Address Monthly/Annual Income Government Resident Special Reason Total Family Meb 1 29824 ANUPAM SAMANTA NEMAI SAMANTA SERVICE C/O ASIT SAMANTA,37 S.N.PAUL ROAD, / / 10,000.00 P.O.-ARIADAH,P.S.-BELGHORIA,KOL-57 6 N 2 03074 ANIL CHANDRA PAL LATE HARENDRA CHANDRA PAL PENSIONER 65/66B, Rani Harshamukhi Road 21/03/84 7,973.00 Block - B, Flat - 6 4 Cal.2 Y 3 00085 SHYAM NARAIN GUPTA BUSINESS 16A, GOPAL MUKHERJEE ROAD 14/05/86 5,000.00 CALCUTTA - 700002 SHORTAGE OF ACCOMODATION 5 N 4 03084 SUSANTA KUMAR SAHA LATE GANESH CHANDRA SAHA SERVICE 29, Harish Neogi Road (Vittadabga) 13/11/87 10,574.00 Cal.67 Long wait for the allotment 5 N 5 02116 PRAVAKAR MANDAL BANKIM CH. MANDAL SERVICE 142/2, A.J.C. BOSE ROAD 10/07/90 4,588.00 CALCUTTA-700 014 SHORTAGE OF SPACE 5 N 6 00997 TAPAS KR BOSE TEACHER 56, BONHOOGHLY GOVT. COLONY 14/01/92 4,403.00 CAL-35 ALLOTTED AT ENTALLY LIG 3 N Page 1 SL Application No Name of Applicant Father/Husband's name Remarks NO Date Occupation Address Monthly/Annual Income Government Resident Special Reason Total Family Meb 7 00517 SAMIR KUMAR NANDI SERVICE 22 N,SRINATH MUKHERJEE LANE, 16/12/92 5,009.00 P.O-GHUGHUDANGA, ECONOMY PROBLEM. -

Authors Chattopadhyay, Shakti Sen, Chanakya

Authors Chattopadhyay, Shakti Sen, Chanakya. Sanyal,Narayan. Ghosh, Shankha. Radhakrishnan, S. (ed.) NCERT & NCERT Experts Froster, E.M. Roy, Prafulla Morsed, Abul Kalam Manjur Mahasweta Devi Rajguru, Saktipada. Mukhopadhyay, Bibhuti Bhusan. Mukhopadhyay, Sirsendu. Chanda, Rani. Mukhopadhyay, Umaprasad. Mukhopadhyay, Ashutosh Basu, Samaresh Roy, Bijaya. Sanyal, Narayan. Taloar, Bhagatram. Abdul Jabbar. Mitra, Ashok. De, Patit Paban. Roy, Satyajit. Ghosh, Jyotirmoy Bhattacharya, Sankarlal Bandapadhyay, Tarashankar Bandapadhyay, Atin. Gupta, Nihar Ranjan. Chaudhury, Satyajit. Chawdhury, Satyajit. Mishro, Niranjan. Bandapadhaya, Amiya Kumar. Shankar (pseudo) Bangla Snatak Path Parsad. (ed.) Sen, Ashok. Thakur, Rabindranath. Sanyal, Kamal Kumar. Sankar Chattopadhyay, Sanjib. Dutta, Hirendranath. Anand, Mukulraj. Bose, Buddhadeva. Chandra, Dipak. Bandhopadhyay, Bibhutibhusan. Bhattacharya, Nimai. Maity, Chittaranjan. Sen, Nilratan. Nath, Ranabir Singha Ray, Jibendra . Sen, Probodhchandra. Ray, Gibendra Singha. Mukhopadhyay, Tarapada. Chattopadhyay, Jyotirmay. Mukhopadhyay, Basanti Kumar. Mishra, Asok Kumar Sen, Arun Kumar. Basu, Suddhasatwa. Dey, Adhir. Majumder, Mohitlal Mukhopadhyay, Sukhomoy. Chattapadhyay, Tapan Kumar Bandopadhyay, Asit Kumar. Bandapadhyay, Asit Kumar. Bandhyapadhyay, Asit Kumar Shaw, Rameshwar. Kalam, Abul Abul Kalam Manjur Morsed Mitra, Dilip Kumar. Sikdar, Ashrukumar. Calcutta University Sanyal, Tarun. Chakraborty, Soumitra Dasgupta, Alokranjan. (auth.) Mukhopadhyay, Amulyadhan Bhattacharya, Kumud Kumar. Abu Sayid Aiyub -

IJHAMS) ISSN (P): 2348-0521, ISSN (E): 2454-4728 Vol

BEST: International Journal of Humanities, Arts, Medicine and Sciences (BEST: IJHAMS) ISSN (P): 2348-0521, ISSN (E): 2454-4728 Vol. 5, Issue 01, Jan 2017, 83-92 © BEST Journals THE FEMALE IN THE MASCULINE WORLD OF SATYAJIT RAY’S FELUDA ARUNIMA SEN PhD Scholar in the Centre for English Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University and Assistant Professor of Matiaburj College, University of Calcutta, India ABSTRACT “The detective story genre is essentially-even when written by women, even when the detectives are female -a "masculine" genre, which reached stasis, if not perfection, by the sixties.”-Marty Roth, in ‘Foul and Fair Play: Reading Genre in Classic Detective Fiction (1995) The detective genre in Bengali suffers an all male universe rid of the restraints that the female is consciously kept outside. This is the crucial point where one addresses the absence of the woman in the Feluda series. Whenever I have discussed the characterization of Feluda, I have been asserting the privileging of the male rationality over feminine intuition or passion has rid the narrative of any space for the woman. Unfortunately, it is a fact that children’s fiction in Bengali, suffers the lack of female characters. Even the genre is called ‘kishoresahitya’ (literature for young males), which quite benignly does away with the ‘kishori’ (young girls) from the scheme of things. Young female readership has been handled extremely callously by authors writing in this genre. It seems like one is forced into a world where one learns to think like a boy, perceive like a boy, read like a boy regardless of the reader’s gender. -

Estate Directorate

ESTATE DIRECTORATE GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL New Secretariat Building, 9th Floor List of Applicants 01/09/14 Name of Estate 60-67 B.T.ROAD Estate Type M.I.G SL Application No Name of Applicant Father/Husband's name Remarks NO Date Occupation Address Monthly/Annual Income Government Resident Special Reason Total Family Meb 1 29824 ANUPAM SAMANTA NEMAI SAMANTA SERVICE C/O ASIT SAMANTA,37 S.N.PAUL ROAD, / / 10,000.00 P.O.-ARIADAH,P.S.-BELGHORIA,KOL-57 6 N 2 03074 ANIL CHANDRA PAL LATE HARENDRA CHANDRA PAL PENSIONER 65/66B, Rani Harshamukhi Road 21/03/84 7,973.00 Block - B, Flat - 6 4 Cal.2 Y 3 00085 SHYAM NARAIN GUPTA BUSINESS 16A, GOPAL MUKHERJEE ROAD 14/05/86 5,000.00 CALCUTTA - 700002 SHORTAGE OF ACCOMODATION 5 N 4 03084 SUSANTA KUMAR SAHA LATE GANESH CHANDRA SAHA SERVICE 29, Harish Neogi Road (Vittadabga) 13/11/87 10,574.00 Cal.67 Long wait for the allotment 5 N 5 02116 PRAVAKAR MANDAL BANKIM CH. MANDAL SERVICE 142/2, A.J.C. BOSE ROAD 10/07/90 4,588.00 CALCUTTA-700 014 SHORTAGE OF SPACE 5 N 6 00997 TAPAS KR BOSE TEACHER 56, BONHOOGHLY GOVT. COLONY 14/01/92 4,403.00 CAL-35 ALLOTTED AT ENTALLY LIG 3 N Page 1 SL Application No Name of Applicant Father/Husband's name Remarks NO Date Occupation Address Monthly/Annual Income Government Resident Special Reason Total Family Meb 7 00517 SAMIR KUMAR NANDI SERVICE 22 N,SRINATH MUKHERJEE LANE, 16/12/92 5,009.00 P.O-GHUGHUDANGA, ECONOMY PROBLEM. -

A Comparative Study of Enid Blyton's the Famous Five and Sasthipada Chattopadhyay's Pandab Goenda

NEW LITERARIA An International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities Volume 1, No. 1, Aug-Sept 2020, PP 65-71 www.newliteraria.com Adolescent Spirit of Adventurism and Inquisitiveness: A Comparative Study of Enid Blyton's The Famous Five and Sasthipada Chattopadhyay's Pandab Goenda Ajay Kumar Gangopadhyay Abstract When a child passes through exposure and experience to the stage of adolescence, she or he is chiefly guided in young imagination by the spirit of adventurism and inquisitiveness. It is both a release from the drab routine life of school and bullying of the elders at home and society, and a way of exerting the new-found ecstasies of life. The virginity of mind searches most eagerly and passionately for the truth, and innocent sense of boldness is ever hungry to unravel the seeming mysteries of life. This paper proposes to make a comparative study of the British writer Enid Blyton and the Bengali writer Shasthipada Chattopadhyay who, despite gaps of place, time and gender, have exploited this spirit most successfully in their respective efforts to tell detective stories involving young boys and girls. In the process, the paper intends to draw attention to an interesting facet of pop-lit, a cult that has already become a part of mainstream literary culture. Keywords: Childhood and Adolescence, Adventurism and Inquisitiveness, Detective Stories, Comics, Graphic Romance In Chapter II of James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as A Youngman, we find an exciting aspect of adolescent awakening. Joyce writes of his young hero Stephen Dedalus newly shifted to Blackrock with his family: 'He became the ally of a boy named Aubrey Mills and founded with him a gang of adventurers in the avenue.