Final Copy 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bora Jevtic. THIRTIETH SESSION

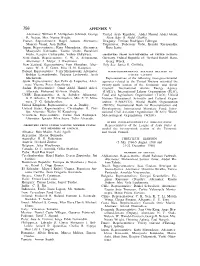

756 APPENDIX V Alternates: William F. McIlquham Schmidt, George United Arab Republic: Abdel Hamid Abdel-Ghani, R. Nelson, Mrs. Nonny Wright. Abou Bakr H. Abdel Ghaffar. France. Representative: Roger Auboin. Alternates: Uruguay: Enrique Rodríguez Fabregat. Maurice Viaud, Jean Duflos. Yugoslavia: Dobrivoje Vidic, Branko Karapandza, Japan. Representative: Koto Matsudaira. Alternates: Bora Jevtic. Masayoshi Kakitsubo, Toshio Urabe, Bunshichi Hoshi, Kenjiro Chikaraishi, Yoshio Ohkawara. OBSERVERS FROM NON-MEMBERS OF UNITED NATIONS Netherlands. Representative: C. W. A. Schurmann. Germany, Federal Republic of: Gerhard Roedel, Hans- Alternates: J. Meijer, J. Kaufmann. Georg Wieck. New Zealand. Representative: Foss Shanahan. Alter- Holy See: James H. Griffiths. nates: W. A. E. Green, Miss H. N. Hampton. Poland. Representative: Jerzy Michalowski. Alternates: INTER-GOVERNMENTAL AGENCIES RELATED TO Bohdan Lewandowski, Tadeusz Lychowski, Jacek UNITED NATIONS Machowski. Representatives of the following inter-governmental Spain. Representative: Jose Felix de Lequerica. Alter- agencies related to the United Nations attended the nate: Vicente Perez Santaliestra. twenty-ninth session of the Economic and Social Sudan. Representative: Omar Abdel Hamid Adeel. Council: International Atomic Energy Agency Alternate: Mohamed El-Amin Abdalla. (IAEA); International Labour Organisation (ILO); USSR. Representative: A. A. Sobolev. Alternates: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO); United G. P. Arkadev, P. M. Chernyshev, Mrs. Z. V. Miro- Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organ- nova, V. G. Solodovnikov. ization (UNESCO); World Health Organization United Kingdom. Representative: A. A. Dudley. (WHO); International Bank for Reconstruction and United States. Representative: Christopher H. Phil- Development; International Monetary Fund; Inter- lips. Alternate: Walter M. Kotschnig. national Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO); World Venezuela. Representative: Carlos Sosa Rodriquez. Meteorological Organization (WMO). Alternates: Ignacio Silva Sucre, Tulio Alvarado. -

Japan and the United Nations (PDF)

Japan and the United Nations Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan Japan's Contribution to the International Community at the UN Foundation of the UN and Japan's Accession to the UN The United Nations (UN) was founded in 1945 under the pledge to prevent the recurrence of war. Eleven years later, in 1956, Japan joined the UN as its 80th member. Since its accession, Japan has contributed to a diversity of fields in UN settings. For example, as of 2014, Japan had served ten times as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council (UNSC). Also, as the only country that has ever suffered from the devastation of atomic bombings, Japan has taken every opportunity to call the importance of disarmament and non-proliferation to the attention of the international community, gaining appreciation and trust from many countries. Today, the international community faces a number of new challenges to be addressed, such as a rash of regional and ethnic conflicts, poverty, sustainable development, climate change, and human rights issues. These global challenges should be addressed by the United Nations with its universal character. For nearly three decades, Japan has been the second largest contributor to the UN's finances after the United States, and Japan is an indispensable partner in the management of the UN. ⓒUN Photo/Mark Garten 1 Japan's Contributions at the UN In cooperation with the UN, Japan contributes to international peace and stability through exercising leadership in its areas of expertise, such as agenda-setting and rule-making for the international community. A case in point is human security. -

![[ 1958 ] Appendices](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0564/1958-appendices-2360564.webp)

[ 1958 ] Appendices

APPENDIX I ROSTER OF THE UNITED NATIONS (As of 31 December 1958) TOTAL AREA ESTIMATED POPULATION (IN THOUSANDS) DATE OF U.N. MEMBER (Square kilometres) Date Total MEMBERSHIP Afghanistan 650,000 1 July 1957 13,000 19 Nov. 1946 Albania 28,748 31 Dec. 1957 1,482 14 Dec. 1955 Argentina 2,778,412 31 Dec. 1958 20,438 24 Oct. 1945 Australia 7,704,159 31 Dec. 1958 9,952 1 Nov. 1945 Austria 83,849 31 Dec. 1957 7,011 14 Dec. 1955 Belgium 30,507 31 Dec. 1957 9,027 27 Dec. 1945 Bolivia 1,098,581 5 Sep. 1958 3,311 14 Nov. 1945 Brazil 8,513,844 31 Dec. 1958 63,466 24 Oct. 1945 Bulgaria 111,493 1 July 1957 7,667 14 Dec. 1955 Burma 677,950 1 July 1958 20,255 19 Apr. 1948 Byelorussian SSR 207,600 1 Apr. 1956 8,000 24 Oct. 1945 Cambodia 172,511 Apr. 1958 4,740 14 Dec. 1955 Canada 9,974,375 1 Dec. 1958 17,241 9 Nov. 1945 Ceylon 65,610 1 July 1958 9,361 14 Dec. 1955 Chile 741,767 30 June 1958 7,298 24 Oct. 1945 China 9,796,973 1 July 1957 649,5061 24 Oct. 1945 Colombia 1,138,355 5 July 1958 13,522 5 Nov. 1945 Costa Rica 50,900 31 Dec. 1958 1,097 2 Nov. 1945 Cuba 114,524 1 July 1958 6,466 24 Oct. 1945 Czechoslovakia 127,859 1 July 1958 13,469 24 Oct. 1945 Denmark 43,042 1 July 1957 4,500 24 Oct. -

![[ 1961 ] Appendices](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0554/1961-appendices-3630554.webp)

[ 1961 ] Appendices

APPENDIX I ROSTER OF THE UNITED NATIONS (As of 31 December 1961) 2 1 DATE OF ADMIS- TOTAL AREA ESTIMATED POPULATION (IN THOUSANDS) MEMBER SION TO U.N. (Square kilometres) Total Date Afghanistan 19 Nov. 1946 650,000 13,800 1 July 1960 Albania 14 Dec. 1955 28,748 1,625 2 Oct. 1960 Argentina 24 Oct. 1945 2,776,656 20,006 30 Sep. 1960 Australia 1 Nov. 1945 7,704,159 10,508 30 June 1961 Austria 14 Dec. 1955 83,849 7,081 1 July 1961 Belgium 27 Dec. 1945 30,507 9,178 31 Dec. 1960 Bolivia 14 Nov. 1945 1,098,581 3,509 5 Sep. 1961 Brazil 24 Oct. 1945 8,513,844 70,799 1 Sep. 1960 Bulgaria 14 Dec. 1955 110,669 7,867 1 July 1960 Burma 19 Apr. 1948 678,033 21,527 1 July 1961 Byelorussian SSR 24 Oct. 1945 207,600 8,226 1 Jan. 1961 Cambodia 14 Dec. 1955 172,511 4,952 1 July 1960 Cameroun 20 Sep. 1960 475,442 4,097 1 July 1960 Canada 9 Nov. 1945 9,976,177 18,238 1 June 1961 Central African Republic 20 Sep. 1960 617,000 1,227 1 July 1960 Ceylon 14 Dec. 1955 65,610 10,167 30 J u n e 1961 Chad 20 Sep. 1960 1,284,000 2,675 31 Dec. 1960 Chile 24 Oct. 1945 741,767 7,340 29 Nov. 1960 China 24 Oct. 1945 9,596,961 656,220 31 Dec. 1957 Colombia 5 Nov. 1945 1,138,338 14,443 5 July 1961 Congo (Brazzaville) 20 Sep. -

UNITED NATIONS LEADERSHIP in the SUEZ CRISIS of 1956 and ITS RAMIFICATIONS in WORLD AFFAIRS Matthew Alw Ker University of Nebraska - Lincoln

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, History, Department of Department of History 11-2010 THE LOST ART OF INTERDEPENDENCY: UNITED NATIONS LEADERSHIP IN THE SUEZ CRISIS OF 1956 AND ITS RAMIFICATIONS IN WORLD AFFAIRS Matthew alW ker University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the History Commons Walker, Matthew, "THE LOST ART OF INTERDEPENDENCY: UNITED NATIONS LEADERSHIP IN THE SUEZ CRISIS OF 1956 AND ITS RAMIFICATIONS IN WORLD AFFAIRS" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 33. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE LOST ART OF INTERDEPENDENCY: UNITED NATIONS LEADERSHIP IN THE SUEZ CRISIS OF 1956 AND ITS RAMIFICATIONS IN WORLD AFFAIRS By Matthew Walker A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor Thomas Borstelmann Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2010 THE LOST ART OF INTERDEPENDENCY: UNITED NATIONS LEADERSHIP IN THE SUEZ CRISIS OF 1956 AND ITS RAMIFICATIONS IN WORLD AFFAIRS Matthew Walker, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2010 Advisor: Thomas Borstelmann The following study examines the relationship between competing national interests and the implementation of multilateral diplomacy as characterized by the United Nations. -

Nlib9280810030.Pdf

The United Nations University is an organ of the United Nations established by the General Assembly in 1972 to be an international community of scholars engaged in research, advanced training, and the dissemination of knowledge related to the pressing global problems of human survival, develop- ment, and welfare. Its activities focus mainly on peace and conflict resolution, development in a changing world, and science and technology in relation to human welfare. The University operates through a worldwide network of research and postgraduate training centres, with its planning and coordinating headquarters in Tokyo. The United Nations University Press, the publishing division of the UNU, publishes scholarly books and periodicals in the social sciences, humanities, and pure and applied natural sciences related to the University’s research. UN Peace-keeping Operations: A Guide to Japanese Policies UN PEACE-KEEPING OPERATIONS: A GUIDE TO JAPANESE POLICIES By L. William Heinrich Jr., Akiho Shibata, and Yoshihide Soeya United Nations a University Press TOKYO u NEW YORK u PARIS ( The United Nations University, 1999 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations University. United Nations University Press The United Nations University, 53-70, Jingumae 5-chome, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo 150-8925, Japan Tel: þ81-3-3499-2811 Fax: þ81-3-3406-7345 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.unu.edu United Nations University Office in North America 2 United Nations Plaza, Room DC2-1462-70, New York, NY 10017, USA Tel: þ1-212-963-6387 Fax: þ1-212-371-9454 E-mail: [email protected] United Nations University Press is the publishing division of the United Nations University. -

(Iowa City, Iowa), 1958-07-18

" The Weather "ltal ruill. 110 <lWUY. COin' Anti-American .!lin. other day." The weather· predicted more thundel" Demonstrations , we (or today, and scattered i wen [or Saturday and Sunday. Irter a walt TIte mercury today is du... to See Photos Page 6 the first u{ moderate a little with highs vary Igles. iIIl from the 70s to the lower BOs. Serving The State University of Iowa and the Peopll ~ of Towa ooo-z~. OOx_ ~ • , Incl WllllO ' Established in 1868 - Fh'e Cents a Copy ~Iember of As.oodated Pre .• ~ Lea~pd Wire aDd Phllto Service Iowa City. Iowa, Friday, July 18. 1958 - Bunnln, o' I, Lumpe 12" lians6 ' loy Sievert line, a two. in the ninth JT-run raUy 1 a Hi vic. anese tJ:PPO[lt Wednesday • • Ine center: 'j 1/', . In the ~ i ay Narles~ 8ritish Rush U.S., Britain Parliament Rallying IllOned from U.N. Adiourns Without ~ to finiih lors' raUy i 2,000 Men Review Action ling. , Mid East Action In Op'position 0 12~ 8 12\t r '004- 7 al l U.N. elkl r91 and Lodge: May Collapse '1~\'.:'lk Eourt. To Jordan If It Fails To Cope With Aggression In Mid East I1<>n, Slev.", Marine Landings King Hussein Asks Help; UNITED NATIONS, N.Y. IA"J - The United Stales warned Thur day Ike, Lloyd Find 'Close latics 2 Charges UAR Plot the U.N. may collapse 1 it fails to cope with a master plot to take over Identity of Views' the Middle East by indirect aggre sion. u.s. Begins Oil Boston Red AMMAN, Jordan 1.fI - Britain U.S. -

54 and 1955, Newspaper Coverage Has Grown by Leaps and Bounds

Union Galendar No, 34 87th Ccmgress, 1st Seuioli ----- Hoitre Report So. 67 A CHRONOLOGY OF MISSILE AND ASTRONAUTIC EVENTS \ L% - \&dl REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE AND ASTRONAUTICS U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES EIGHTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Serial b \ ! '.' I 1' , 'I 1 I ]A, I ,J i ;I J@(6AAclf8, 1961.- Comniittetl to thc Coninlittee of the N'liole House on ' i ~ the qate of the Union and ordered to be printed ! I _I. I lJ S. GOVERNMENT PRIN'I'ING OVF'IC'I.: 1 64426 WASHIN(:TON . I!)fil 4 6 I ! i i j 1 I! I I LETTER OF SUBMITTAL HOUSEOF REPRESENTATIVES, COMMITTEEON SCIENCEAND ASTRONAUTICS, Washington, D.C., March 8, 1961. Hon. SAMRAYBURN, Speaker of the House of Representatitles, Washington, D.C. DEARMR. SPEAKER:By direction of the Committee on Science and Astronautics, I submit the following report on “A Chronology of Missile and Astronautic Events” for the consideration of the 87th Congress. Two reports issued by the predecessor Select Commiftee on Astro- nautics and Space Exploration included chronologies which have proved useful to many readers interested in our emerging missile and space capabilities and in world progress in these areas. It has seemed useful to expand slightly upon the original efforts and to bring the revised listings up to date. The chronology must be viewed as preliminary. Although an effort has been made to make it correct, unofficial sources have been relied upon quite heavily in order to widen the coverage. Dr. Charles S. Sheldon 11, technical director of the committee, supplemented his main Compilation with a few items collected either by the Legislative Reference Service of the Library of Congress or by the Historian of the , wational Aeronautics and Space Administration. -

Explaining the Dispatch of Japan's Self- Defense

LEARNING HOW TO SWEAT: EXPLAINING THE DISPATCH OF JAPAN’S SELF- DEFENSE FORCES IN THE GULF WAR AND IRAQ WAR By Jeffrey Wayne Hornung A Dissertation Submitted To The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences Of the George Washington University In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 31, 2009 Dissertation directed by Mike Mochizuki Associate Professor of Political Science and International Affairs The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Jeffrey Wayne Hornung has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of July 13, 2009. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. LEARNING HOW TO SWEAT: EXPLAINING THE DISPATCH OF JAPAN’S SELF- DEFENSE FORCES IN THE GULF WAR AND IRAQ WAR Jeffrey Wayne Hornung Dissertation Research Committee: Mike Mochizuki , Associate Professor of Political Science and International Affairs Dissertation Director James Goldgeier , Professor of Political Science and International Affairs Committee Member Deborah Avant , Professor of Political Science, University of California-Irvine Committee Member ii © Copyright 2009 by Jeffrey Wayne Hornung All rights reserved iii To Maki Without your tireless support and understanding, this project would not have happened. iv Acknowledgements This work is the product of four years of research, writing and revisions. Its completion would not have been possible without the intellectual and emotional support of many individuals. There are several groups of people in particular that I would like to mention. First and foremost are two individuals who have had the greatest impact on my intellect regarding Japan: Nat Thayer and Mike Mochizuki. -

~ T Angus Maclnnis, 1.884—1964 an Inventory of His Papers in The

S ~ tN T Angus Maclnnis, 1.884—1964 An Inventory of His Papers in The Library of the University of British Columbia Special Collections Division ~e~ared - - / Scott A. Griffin - June, 1979 Revised by Jennifer Roberts Important note for access: The Angus MacInnis fonds is physically stored in the Angus MacInnis memorial collection. To access these files, please request the following boxes from the Angus MacInnis memorial collection (RBSC-ARC-1011). o Box 70 o Box 71 o Box 72 o Box 73 o Box 74 o Box 75 11 TABLE OF CONTEW1~S Introduction ill. Inventory Serips Scrapbooks 1. Correspondence: incoming and outgoing 13. Correspondence: other 29. Subject files 29. Speeches 32. Notes 32. Memorabilia 33. Miscellaneous - 33. Printed Material 33. P iii Introduction Angus MacTnnia, 1884—1964 Angus Maclnnis was born in 1884 at Glen Williams on Prince Edward Islnnd. Gaelic was spoken in his home and he did not learn English until attending school. Upon his arrival in Vancouver in 1908, Angus found a • job driving a milk wagon seven days a weeks !ISro years later he obtained employment with B.C. Electric,-as a streetcar conductor. Active in his union, he soon became business, agent for the Street and Railway union. • Though born a Tory, Angus became a socialist upon viewing the injustices of the 1911 Nsnmimo coal strike. In 1918 he became a member of the Federated Labor Party, and later joingd~the Independent labor Party. He entered civic politics in 1922, winning a School Board seat for two years. lie sat as an alderman on the City Council from 1926 until 1930. -

INFORME DEL CONSEJO DE SEGURIDAD ! LA ASAMBLEA GENERAL 16 Di' Julio Di' 1958 - 15 Di' Julio Di' 1951

- .. -- UNIDAS R E e F' r'll:" 'J 2 OCT 1959 INDEX SfC7 '0,. I HiR.Uv INFORME DEL CONSEJO DE SEGURIDAD ! LA ASAMBLEA GENERAL 16 dI' julio dI' 1958 - 15 dI' julio dI' 1951 ASAMBLEA GENERAL DOCUMENTOS OFICIALES 1 PECIM~:~ PERI~ DE SESIQ~~ ª,UPLEMENIQ~. 2. (AI4190) NUEVA YORK .. -- --..-...... - - ,... .... I NACIONES UNIDAS INFORME DEL CONSEJO DE SEGURIDAD A LA ASAMBLEA GENERAL 16 de juUo de 1958 - 15 de julio de 1959 ASAMBLEA GENERAL DOCUMENTOS OFICIALES : DECIMOCUARTO PERIODO DE SESIONES SUPLEMENTO No. 2 (A/4190> NUEVA YORK, 1959 ,...... - .. - I "J -- ~ ! '., \ l r \ I ¡.. l NOTA I I Las signaturas de los documentos de las Naciunes Unidas se componen de letras mayúsculas y cifras. La simple mencí6n de una de tales signaturas indica que se hace referencia a un documento ele las Naciones Unidas. 4 ¡, I j I \ r l .' ... ...... "-- "-- ..... ' - == INDICE Página INTRODUCCIÓN. ..•..............•..•..•.....•..•..•...•..•.•...•.•..••.• V PARTE 1 Cuestiones examinadas por el Consejo de Seguridad en virtud de su· respcngabilidad de mantener la paz y la seguridad internacionales l Capítulo 1. CARTA DE FECHA 22 DE MAYO DE 1958 DIRIGIDA AL PRESIDENTE DEL CON r \ SEJO DE SEGURIDAD POR EL REPRESENTANTE DEL LÍBANO RELATIVA A: I "DENUNCIA PRESENTADA POR EL LÍBANO EN RELACIÓN CON UNA SITUACIÓN ORIGINADA POR LA INTERVENCIÓN DE LA REPÚBLICA ARABE UNIDA EN I ros ASUNTOS INTERNOS DEL LÍBANO, CUYA CONTINUACIÓN ES SUSCEPTIB>:.E DE PONER EN PELIGRO EL MANTENIMIENTO DE LA PAZ Y LA SEGURIDAD .,t INTERNACIONALES" ............•..•..•' ......•..•.•..•..•..•.••.•.• 1 CARTA DE 'FECHA 17 DE JULIO DE 1958 DIRIGiDA AL PRESIDENTE DEL CCN l SEJO DE SEGURIDAD POR EL REPRESENTANTE DE JORDANIA RELATIVA A: I "DENUNCIA DE INGERENCIA EN SUS ASUNTOS INTERNOS PRESENTADA POR I EL REINO HACHEMITA DE J ORDANIA CONTRA LA REPÚBLICA ARABE UNIDA" . -

REPORT of the SECURITY COUNCU to the GENERAL ASSEMBLY 16 July 1958 to 15 July 1959

~m'.~~~~!RB_"_""..... "'_Bii_~;·'/' UNITED NATIONS REPORT OF THE SECURITY COUNCU TO THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY 16 July 1958 to 15 July 1959 GENERAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL RECORDS : FOURTEENTH SESSION SUPPLEMENT No. 2 (A!4190) ( 45 p.) NEW YORK · , UNITED NATIONS REPORT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL TO THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY 16 July 1958 to 15 July 1959 GENERAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL RECORDS : FOURTEENTH SESSION SUPPLEMENT No. 2 CA/4190> New York, 1959 - T NOTE Symbois of l"nited Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ,.Li < ,.1 " ,to .....- ,·'-'-T~~'~'-"~""-' ,.""~=,,,•.,,._-~~~._~-- ) TABLE OF CONTENTS ) Page INTRODUCTION I ...... , '" . V PART I r Questions considered by the Security Council under its responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security I, Cha.pter 1. LETTER DATED 22 MAY 1958 FROM THE REPRESENTATIVE OF LEBANO:N ADDRESSED TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL CONCERNING: "COMPLAINT BY LEBANON IN RESPECT OF A SITUATION ARISING FROM THE INTERVENTION OF THE UNITED ARAB REPUBLIC IN THE INTERNAL AFFAIRS OF LEBANON, THE CONTINUANCE OF \VHICH Is LIKELY 1'0 ENDANGER THE MAINTENANCE OF INTERNATIONAL PEACE AND SECURITY" . 1 LETTER DATED 17 JULY 1958 FROM THE REPRESENTATIVE OF JORDAN ADDRESSED TO THE PRES;DENT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL CONCERN ING: "COMPLAINT BY THE HASHEMITE KINGDOM OF JORDAN OF INTER FERENCE IN ITs DOMESTIC AFFAIRS BY THE UNITED ARAB REPUBLIC" .. 1 A. Further consideration of the complaint by Lebanon . 1 B. Submission of the complaint by Jordan . 3 C. Security Council resolution of 7 August 1958 .