Competition Neutrality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Global Volatility Steadies the Climb

WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS Global volatility steadies the climb Cirium Fleet Forecast’s latest outlook sees heady growth settling down to trend levels, with economic slowdown, rising oil prices and production rate challenges as factors Narrowbodies including A321neo will dominate deliveries over 2019-2038 Airbus DAN THISDELL & CHRIS SEYMOUR LONDON commercial jets and turboprops across most spiking above $100/barrel in mid-2014, the sectors has come down from a run of heady Brent Crude benchmark declined rapidly to a nybody who has been watching growth years, slowdown in this context should January 2016 low in the mid-$30s; the subse- the news for the past year cannot be read as a return to longer-term averages. In quent upturn peaked in the $80s a year ago. have missed some recurring head- other words, in commercial aviation, slow- Following a long dip during the second half Alines. In no particular order: US- down is still a long way from downturn. of 2018, oil has this year recovered to the China trade war, potential US-Iran hot war, And, Cirium observes, “a slowdown in high-$60s prevailing in July. US-Mexico trade tension, US-Europe trade growth rates should not be a surprise”. Eco- tension, interest rates rising, Chinese growth nomic indicators are showing “consistent de- RECESSION WORRIES stumbling, Europe facing populist backlash, cline” in all major regions, and the World What comes next is anybody’s guess, but it is longest economic recovery in history, US- Trade Organization’s global trade outlook is at worth noting that the sharp drop in prices that Canada commerce friction, bond and equity its weakest since 2010. -

ICAO Regional Workshop on CORSIA, 7 to 8 April 2019 Cairo, Egypt (MID)

ICAO Regional Workshop on CORSIA, 7 to 8 April 2019 Cairo, Egypt (MID) LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Dialogue States/Organization Credentials Group CANADA Mr. Gilles Bourgeois 1. D Chief, Environmental Protection and Standards (Facilitator) Transport Canada EGYPT Mr. Mohammed Abo El Khair 2. Senior ATSEP D Egypt National Air Navigation Services Company (NANSC) Mr. Elsayed Abdelghafar 3. General Director, Ground Handling Facility Equipment D Egyptian Civil Aviation Authority Amr Nagaty 4. Airwothness Inspector B Egyptian Civil Aviation Authority Mr. Mostafa Ali 5. Airworthiness Inspector A Egyptian Civil Aviation Authority Mr. Tamer Ibrahim Mahmoud 6. Airworthiness Inspector C Egyptian Civil Aviation Authority Mr. Ahmed Hafez 7. OCC Manager A Fly Egypt Airline Mr. Ahmed Attour 8. Aircraft performance engineer C Nileair Mr. Mostafa Mowafy 9. Head of Environmental Regulations A EgyptAir Holding Company Mr. Ibrahim Farhat 10. Head of Statistics and Operation Research B EgyptAir Holding Company ICAO Regional Workshop on CORSIA, 7 to 8 April 2019 Cairo, Egypt (MID) Mr. Mohamed Elshenawy 11. General Manager, Fuel and Emissions D EgyptAir Holding Company Mr. Ahmed Ebrahim 12. Navigation and Traffic General Manager A Petroleum Air Services Mr. Ahmed Goda 13. Industry Affairs Specialist C EgyptAir Holding Company Mr. Sherif Zolfokar 14. Power Plant Manager D Petroleum Air Services Mr. Ayman Anwar 15. Quality Assurance Manager B Air Cairo Mr. Amr Elhennawy 16. Operations Engineer C Nesma Airlines Mr. Fathy Kabil 17. Safety and Quality Director B Air Cairo Mr. Mostafa Darwish 18. Quality Assurance Manager D Air Arabia Mr. Reda Elbllat 19. Technical Services Engineer D Air Arabia Mr. Wael Khalifa 20. -

RASG-MID/6-WP/15 17/08/2017 International Civil Aviation Organization Regional Aviation Safety Group

RASG-MID/6-WP/15 17/08/2017 International Civil Aviation Organization Regional Aviation Safety Group - Middle East Sixth Meeting (RASG-MID/6) (Bahrain, 26-28 September 2017) Agenda Item 3: Regional Performance Framework for Safety SMS IMPLEMENTATION BY AIR OPERATORS (Presented by IATA) SUMMARY This paper provides the status of SMS implementation by Air operators registered in MID States and provides recommendation for the way forward to complete SMS implementation. Action by the meeting is at paragraph 3. REFERENCES - SST-3 Meeting Report 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Currently, implementation of safety management at the Service Provider level is variable, and is proving challenging to put in place the system as intended by Annex 19. 1.2 The MID-SST was established to support the RASG-MID Steering Committee (RSC) in the development, monitoring and implementation of Safety Enhancement Initiatives (SEIs) related to identified safety issues, including implementation of State Safety Programs (SSP) and Safety Management Systems (SMS). 2. DISCUSSION 2.1 The Third meeting of the MID Safety Support Team (MID-SST/3) held in Abu Dhabi, UAE, 10-13, recognized the need to monitor the status of SMS implementation by air operators, maintenance organizations and training organizations involved in flight training; in order to take necessary actions to overcome the challenges faced and to improve safety. 2.2 In this regard, the meeting agreed that IATA with the support of the ICAO MID Office will provide feedback and a plan of actions to address SMS implementation by air operators. RASG-MID/6-WP/15 - 2 - 2.3 The meeting may wish to note that Safety Management Systems (SMS) is an integral part of the IOSA program. -

Entry Barriers Facing Egyptian Private Air Carriers in Egypt

Journal of Tourism & Sports Management (JTSM) (ISSN: 2642-021X) 2020 SciTech Central Inc., USA Vol. 3 (2) 269-287 ENTRY BARRIERS FACING EGYPTIAN PRIVATE AIR CARRIERS IN EGYPT Alaa Ahmed Ashour1 Captain Airbus A340/330 Egypt Air, Ex. President Egyptian Civil Aviation Authority, Egypt Ghada Aly Hammoud Tourism Marketing, Helwan University, Egypt Dean Faculty of Tourism and Hotel Management, Bani Sweif University, Egypt Hala Foad Tawfik Faculty of Tourism and Hotel Management, Helwan University, Egypt Received 22nd July 2020; Revised 29th July 2020; Accepted 31st July 2020 ABSTRACT The Egyptian aviation policy aims to promote travel and tourism to stimulate the economy. This will need the active participation of both the state-owned carriers and the private carriers. Entry barriers that are facing the Egyptian private air carriers in Egypt are clearly identified and analyzed. An in-depth interview with 21 executives of the Private air carriers is carried out using a survey to identify those barriers in the Egyptian market. The information obtained from both the interviews and the survey highlighted that there are several entry barriers facing the Egyptian private air carriers, the major factor of these barriers would be the protective nature of the Egyptian Aviation policy toward the State-owned incumbent carrier. Egyptian Civil Aviation Authority should initiate policies and procedures to reduce the barriers to entry and propose economic regulation to ensure fair competition and prevent anticompetitive behavior of the incumbent. Keywords: Deregulation, New entrants, Barriers to entry, Substantial ownership, Effective control. INTRODUCTION There are several studies that addressed the barriers to entry in the US and Europe within the legal and economic environment of these continents. -

World Airliner Census 2015 WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS World Airliner Census 2015 World Airliner Census 2015

FL IGINTERNHTAT IONAL WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS 2015 WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS 2015 WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS 2015 pared to wait for equipment that they need as soon as possible, Toulouse and Seattle have been in the envious position over the past few years of enjoying robust demand for their existing aircraft MAKING IT types, even though their successors are waiting in the wings. This has not been the case in wide- bodies, where production of, for example, the A330 is tailing off as Airbus prepares to intro- COUNT duce the A330neo. Our annual snapshot of the global airliner fleet shows CLOSE TALLIES The A320 family still tops the list of most popu- deliveries of current single-aisle types are holding up, lar mainline aircraft, although it is just pipped if while the 787 has debuted in the top 10 mainline aircraft older-generation Boeing 737s are added to the tally. In total there are some 6,100 Boeing nar- rowbodies in service (not counting the 717 and earlier McDonnell Douglas variants, of which MURDO MORRISON LONDON According to Flightglobal’s latest annual air- there are 666), compared with 6,052 of the A320, DATA ANALYSIS ANTOINE FAFARD liner census – a breakdown of the world’s fleet which does not, of course, have an earlier vin- of commercial aircraft by type and operator – tage equivalent. A year ago, it looked like the irlines, it seems, cannot get enough of numbers of current-generation A320s and 737s A320 would soon overtake the 737 if old and Airbus and Boeing narrowbodies. With in service rose by 7.9% and 9.1%, respectively. -

Current Conditions of Borg El Arab International Airport

The Arab Republic of Egypt Egyptian Holding Company for Airports and Air Navigation (EHCAAN) Egyptian Airports Company (EAC) The Arab Republic of Egypt Special Assistance for Project Implementation (SAPI) for Borg El Arab International Airport Modernization Project Final Report February 2012 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Japan Airport Consultants, Inc. Narita International Airport Corporation (NAA) Joint Venture Special Assistance for Project Implementation (SAPI) Borg El Arab International Airport Modernization Project Table of Contents – Final Report - Table of Contents Table of Contents List of Tabulations List of Illustrations List of Abbreviations Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Preface .................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Outline of the Study ............................................................................................... 1-2 1.2.1 Objective of the Study ................................................................................... 1-2 1.2.2 Area of the Study ........................................................................................... 1-2 1.2.3 Scope of Study .............................................................................................. 1-3 1.3 Work Procedure of the Study................................................................................ 1-4 1.3.1 Study Organization ........................................................................................ 1-4 1.3.2 Work -

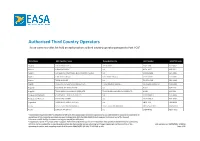

Authorised Third Country Operators the Air Carriers on This List Hold an Authorisation As Third Country Operator Pursuant to Part-TCO¹

Authorised Third Country Operators The air carriers on this list hold an authorisation as third country operator pursuant to Part-TCO¹. State Name AOC Operator Name Doing Business As AOC Number EASA TCO code Albania AIR ALBANIA SH.P.K. AIR ALBANIA AL-02-ABN ALB-0002 Albania ALBAWINGS SHPK n/a AL-01-AWT ALB-0001 Algeria AIR ALGERIE, COMPAGNIE DE TRANSPORT AERIEN n/a TA/001/1998 DZA-0001 Algeria STAR AVIATION spa STAR AVIATION spa TA/003/2002 DZA-0002 Algeria TASSILI AIRLINES n/a TA/002/1998 DZA-0003 Angola TAAG-LINHAS AEREAS DE ANGOLA, S.A. TAAG-ANGOLA AIRLINES AO-001/09-13/21DTA AGO-0001 Anguilla ANGUILLA AIR SERVICES LTD n/a A/322 AIA-0002 Anguilla TRANS ANGUILLA AIRWAYS (2000) LTD TRANS ANGUILLA AIRWAYS (2000) LTD A/413 AIA-0001 Antigua and Barbuda CALVINAIR HELICOPTERS LIMITED n/a 2A/12/003BH ATG-0003 Antigua and Barbuda LIAT (1974) LIMITED n/a 2A/12/003 A ATG-0002 Argentina AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS S.A. n/a ANAC-101 ARG-0001 Aruba AEGLE AVIATION (ARUBA) N.V. AEGLE AVIATION (ARUBA) AUAAPN-2018/01 ABW-0004 Aruba COMLUX ARUBA N.V. n/a CXBAPN002 ABW-0001 ¹ Commission Regulation (EU) No 452/2014 of 29 April 2014 laying down technical requirements and administrative procedures related to air operations of third country operators pursuant to Regulation (EC) No 2016/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council ² Persuant to ART.205(b) of Commission Regulation (EU) No 452/2014 ³ Regulation (EC) No 2111/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Counsil of 14 December 2005 on the establishment of a Community list of air carriers subject to an operating ban within the Community and on informing air transport passengers of the identity of the Last updated on: 23/09/2021 13:00:53 operating air carrier, and repealing Article 9 of Directive 2004/36/EC (OJ 344, 27.12.2005, p. -

بسم هللا الرحمن الرحيم قسم هندسة الطيران والفضاء 1938 - 2019 Aeronautical Engineering and Aviation Management (AEM) Content

بسم هللا الرحمن الرحيم قسم هندسة الطيران والفضاء 1938 - 2019 Aeronautical Engineering and Aviation Management (AEM) Content 1. Aviation world 2. World growth of airtransport 3. Program outlines 4. Engineering Maintenance 5. Aviation Management 6. Our senior 2 students status 1. AviationWorld 2. World Growth of Airtransport Passenger Demand Growth 1990-2030 Revenue Passenger Kilometers (RPK) Billions) Air traffic growth by area Area Passenger Freight annual growth annual growth Africa 6.1% 6.9% Middle East 5.9% 6.3% Asia 6.0% 5.7% Latin America 5.8% 5.5% Europe 3.7% 3.1% North America 3.1% 2.9% World Fleet Forecast 2010-2030 Egyptian Airliners COMMENCED COMMENCED Airline OPERATIONS Airline OPERATIONS Air Arabia Egypt 2009 Aviator Airlines 2015 Air Cairo 2003 Cairo Aviation 1998 Air Go Airlines (Egypt) 2013 EgyptAir 1932 Air Leisure 2013 EgyptAir Cargo 2004 EgyptAir Air Sinai 1982 2006 Express Alexandria Airlines 2007 FlyEgypt 2014 AlMasria Universal 2008 Nesma Airlines 2010 Airlines AMC Airlines 1992 Nile Air 2008 Smart Aviation Petroleum Air 2007 1982 Company Services Status of Aeronautics Some countries are involved in aerospace industries but too many are not. Almost all countries are involved in civil aviation. A field that is exponentially growing. Fleet doubles every 20 years, confirmed by multiple studies including: This creates high demand for jobs in a top level field locally and abroad. Demand for Civil Aviation Maintenance Engineers Total number of required new engineers in the next 20 years in the airtransport field is estimated at 550000 Evolution of a new program Aeronautical Engineering and Aviation Management The Aerospace Department appreciates the ever growing field of airtransport world wide and its very high growth rate in our sphere (Middle east and Africa) and further on its direct and indirect impact on the Egyptian economy. -

Cairo International Airport (Cai/Heca) Briefing & Aerodrome Charts

HECA Briefing & Aerodrome Charts v2.0 CAIRO INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (CAI/HECA) BRIEFING & AERODROME CHARTS DOCUMENT VERSION 2.0 JANUARY 2019 NOT FOR REAL LIFE USE. VATSIM USE ONLY. 1 HECA Briefing & Aerodrome Charts v2.0 ! Usage Notice This document is to be used for simulation purposes only. It should only be utilized for virtual air traffic on the VATSIM Network that EGvACC is affiliated with. The Network, Division, and EGvACC are in no way responsible for the potentially deadly consequences of using this information in any other manner than on a virtual air traffic network. This document is copyrighted by © EGvACC at http://www.vateg.net. Obtaining this document from any source other than via a page residing on http://www.vateg.net is prohibited. ! تحذیر ﻻ یستخدم ھذا الملف او اي مواد مرتبطة به في الطیران الحقیقي او في التخطیط لرحلة في الواقع. تم اعداد ھذا الملف للطیران التشبیھي فقط لتوفیر ھذه المعلومات للھواة. نحن ﻻ نتحمل اي مسئولیة عن استخدامھا او ما یترتب علي استخدامھا في الطیران الحقیقي. NOT FOR REAL LIFE USE. VATSIM USE ONLY. 2 HECA Briefing & Aerodrome Charts v2.0 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Aerodrome Information .................................................................................................................. 4 3. Runways and Approaches in Use .................................................................................................... 4 4. Nearby NAVAIDs ......................................................................................................................... -

World Airliner Census 2016 Airbus WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS World Airliner Census 2016

WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS 2016 Airbus WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS 2016 EXPLANATORY NOTES This census data covers all commercial jet and turbo- where applicable, the outstanding firm orders in pa- nies – such as China Aviation Supplies – are excluded, prop-powered transport aircraft in service or on firm rentheses in the right-hand column. In Flight Fleets unless a confirmed end-user is known; in which case order with airlines worldwide, excluding aircraft that Analyzer, an airliner is defined as being in service if it is the aircraft is shown against the airline concerned. carry fewer than 14 passengers or equivalent cargo. It active (in other words accumulating flying hours). Operators’ fleets include leased aircraft. records the fleets of Western, China-built and Russia/ An aircraft is classified as parked if it is known to be CIS/Ukraine-built airliners. inactive – for example, if it is grounded because of ABBREVIATIONS The tables have been compiled using the Flight airworthiness requirements or in storage – and when AR: advanced range (Embraer 170/190/195) Fleets Analyzer database. The information is correct flying hours for three consecutive months are report- C: combi or convertible up to July 2016 and excludes non-airline operators, ed as zero. Aircraft undergoing maintenance or await- ER: extended range such as leasing companies and the military. ing conversion are also counted as being parked. ERF: extended range freighter (747 and 767) Aircraft are listed in alphabetical order, first by man- The region is dictated by operator base and does F: freighter ufacturer and then type. Operators are listed by re- not necessarily indicate the area of operation. -

Mints – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY

No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 5 CIVIL AVIATION AND PIPELINE SECTOR March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 5 CIVIL AVIATION AND PIPELINE SECTOR March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 USD1.00 = EGP5.96 USD1.00 = JPY77.91 (Exchange rate of January 2012) MiNTS: Misr National Transport Study Technical Report 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Page CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................1-1 1.1. BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2. THE MiNTS FRAMEWORK.................................................................................................................1-1 1.2.1. Study Scope and Objectives.......................................................................................................1-1