Re-Evaluating the Art & Chess of Marcel Duchamp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions As of August 1, 2002 Note to the Reader The works of art illustrated in color in the preceding pages represent a selection of the objects in the exhibition Gifts in Honor of the 125th Anniversary of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Checklist that follows includes all of the Museum’s anniversary acquisitions, not just those in the exhibition. The Checklist has been organized by geography (Africa, Asia, Europe, North America) and within each continent by broad category (Costume and Textiles; Decorative Arts; Paintings; Prints, Drawings, and Photographs; Sculpture). Within each category, works of art are listed chronologically. An asterisk indicates that an object is illustrated in black and white in the Checklist. Page references are to color plates. For gifts of a collection numbering more than forty objects, an overview of the contents of the collection is provided in lieu of information about each individual object. Certain gifts have been the subject of separate exhibitions with their own catalogues. In such instances, the reader is referred to the section For Further Reading. Africa | Sculpture AFRICA ASIA Floral, Leaf, Crane, and Turtle Roundels Vests (2) Colonel Stephen McCormick’s continued generosity to Plain-weave cotton with tsutsugaki (rice-paste Plain-weave cotton with cotton sashiko (darning the Museum in the form of the gift of an impressive 1 Sculpture Costume and Textiles resist), 57 x 54 inches (120.7 x 115.6 cm) stitches) (2000-113-17), 30 ⁄4 x 24 inches (77.5 x group of forty-one Korean and Chinese objects is espe- 2000-113-9 61 cm); plain-weave shifu (cotton warp and paper cially remarkable for the variety and depth it offers as a 1 1. -

Montenegro Chess Festival

Montenegro Chess Festival 2 IM & GM Round Robin Tournaments, 26.02-18.03.2021. Festival Schedule: Chess Club "Elektroprivreda" and Montenegro Chess Federation organizing Montenegro Chess Festival from 26th February to 18th March 2021. Festival consists 3 round robin tournaments as follows: 1. IM Round Robin 2021/01 - Niksic 26th February – 4th March 2. IM Round Robin 2021/02 - Niksic 5th March – 11th March 3. GM Round Robin 2021/01 - Podgorica 12th March – 18th March Organizer will provide chess equipment for all events, games will be broadcast online. Winners of all tournaments receive trophy. You can find Information about tournaments on these links: IM Round Robin 2021/01 - https://chess-results.com/tnr549103.aspx?lan=1 IM Round Robin 2021/02 - https://chess-results.com/tnr549104.aspx?lan=1 GM Round Robin 2021/01 - https://chess-results.com/tnr549105.aspx?lan=1 Health protection measures will be applied according to instructions from Montenegro institutions and will be valid during the tournament duration. Masks are obligatory all the time, safe distance will be provided between the boards. Organizer are allowed to cancel some or all events in the festival if situation with pandemic requests events to be cancelled. Tournaments Description: Round Robin tournaments are closed tournaments with 10 participants each and will be valid for international chess title norms. Drawing of lots and Technical Meeting for each event will be held at noon on the starting day of each tournament. Minimal guaranteed average rating of opponents on GM tournament is 2380 and 2230 on IM tournament. Playing schedule: For all three tournaments, double rounds will be played second and third day. -

HARD FACTS and SOFT SPECULATION Thierry De Duve

THE STORY OF FOUNTAIN: HARD FACTS AND SOFT SPECULATION Thierry de Duve ABSTRACT Thierry de Duve’s essay is anchored to the one and perhaps only hard fact that we possess regarding the story of Fountain: its photo in The Blind Man No. 2, triply captioned “Fountain by R. Mutt,” “Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz,” and “THE EXHIBIT REFUSED BY THE INDEPENDENTS,” and the editorial on the facing page, titled “The Richard Mutt Case.” He examines what kind of agency is involved in that triple “by,” and revisits Duchamp’s intentions and motivations when he created the fictitious R. Mutt, manipulated Stieglitz, and set a trap to the Independents. De Duve concludes with an invitation to art historians to abandon the “by” questions (attribution, etc.) and to focus on the “from” questions that arise when Fountain is not seen as a work of art so much as the bearer of the news that the art world has radically changed. KEYWORDS, Readymade, Fountain, Independents, Stieglitz, Sanitary pottery Then the smell of wet glue! Mentally I was not spelling art with a capital A. — Beatrice Wood1 No doubt, Marcel Duchamp’s best known and most controversial readymade is a men’s urinal tipped on its side, signed R. Mutt, dated 1917, and titled Fountain. The 2017 centennial of Fountain brought us a harvest of new books and articles on the famous or infamous urinal. I read most of them in the hope of gleaning enough newly verified facts to curtail my natural tendency to speculate. But newly verified facts are few and far between. -

The Evects of Time Pressure on Chess Skill: an Investigation Into Fast and Slow Processes Underlying Expert Performance

Psychological Research (2007) 71:591–597 DOI 10.1007/s00426-006-0076-0 ORIGINAL ARTICLE The eVects of time pressure on chess skill: an investigation into fast and slow processes underlying expert performance Frenk van Harreveld · Eric-Jan Wagenmakers · Han L. J. van der Maas Received: 28 November 2005 / Accepted: 3 July 2006 / Published online: 22 December 2006 © Springer-Verlag 2006 Abstract The ability to play chess is generally Introduction assumed to depend on two types of processes: slow processes such as search, and fast processes such as One of the important challenges for cognitive science is pattern recognition. It has been argued that an increase to shed light on the processes that underlie expert in time pressure during a game selectively hinders the decision making. Across a wide range of Welds such as ability to engage in slow processes. Here we study the medical decision making and engineering, it has been eVect of time pressure on expert chess performance in shown that expertise involves both slow processes order to test the hypothesis that compared to weak such as selective search and fast processes such as the players, strong players depend relatively heavily on recognition of meaningful patterns (e.g., Ericsson & fast processes. In the Wrst study we examine the perfor- Staszewski 1989). This distinction between fast and slow mance of players of various strengths at an online chess processes is very applicable to the game of chess and server, for games played under diVerent time controls. therefore research on chess is of considerable impor- In a second study we examine the eVect of time con- tance for the understanding of expert performance. -

Sarajevo 1967 ° "' 1 '"

Grondmaster ayme, lefl, explafntnq the qallle 01 d»eu to 80"011, c.nter, and USSR Champion Stein, Byrne later floated SteIn 10 anOfher leuon o"er the board. accountmq tor Sleln's only lou 01 lhe lournamenl, SARAJEVO 1967 I 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 W L D !: ~~::: :::::::::::::::::::::.:.... .::: :' .' ...: . ~ ~~, ---.-~;.-.::~;--:~;-"~,==~: =~~f. =~"tl =j~~=;~t="ii"'\'----;.~:;:--;"-;-·I - ::- -;:===-;~'----;~'---";:""~=- 10 ~ .4- ~ 3. tknko , If.! Y.i: % 0 I 0 1 1 I ~ I \ _ ;-1 _~'~ ,;--;;-, - \1)-5 x 1h 'h ':-l - '--'' 1 I I 1 'h I 0 I ,';-,,'c-- -:';-_-- 1().5_ °1 '""' 1h x 0 0 n 1 n I ¥, I 1 1 I ,..' .....;:3_ ~ 9Ik.5 ~ h 1 x I,i h ~ 1 n h I I,i 1;.--:1_ _ 5 1 9 9h . ~~ ° "1 h 1 I,i x 0 I 'h 0 1 "':"''-''''7----:-1 t 6" 5'- - 8'7 .6% o o lit liz 1 x 1,1: .., .., 1 "':t I t ¥l -.' , 2 ~ 81.1 f1lh 1 0 0 n 0 If. :< 0 0 1 J I n _ -;-I _ ';--;-6_ ,_ _ ,.. - 11 Duc1n tcin .. .. .... ... n ~ ~ ~ ~ : ~ "~'- : : ~ ~ ~ --,~,,-:~:-~ ----.-~ :: ~! 12. Ja.noS('vic .... ... ... ... .. ~_-;";... _~ ~ _Ifl "1 ;;:0'--;,;..0 _ 0,,-:"':-"''7--;;:''--''''' 1 ~"''-.;.I _ _.;:-' _ ;!i 8 f.. 9 13. Pict%.Sch ................................... \o!t Vr 'tit;. _ ";. ,-~O:- 0 n 'fl 0 0 . __1 'h x 0 1:'.1 0 1 6 --;8- - - 5- 10 14. Bogdanuvic .. .................. Y.t 0 0 0 0 lit Yt 0 0 Yt 1 0 I x 0 h 2 8 5 _ _ " "1.100" :~ : ~:~;:~. -

No. 123 - (Vol.VIH)

No. 123 - (Vol.VIH) January 1997 Editorial Board editors John Roycrqfttf New Way Road, London, England NW9 6PL Edvande Gevel Binnen de Veste 36, 3811 PH Amersfoort, The Netherlands Spotlight-column: J. Heck, Neuer Weg 110, D-47803 Krefeld, Germany Opinions-column: A. Pallier, La Mouziniere, 85190 La Genetouze, France Treasurer: J. de Boer, Zevenenderdrffi 40, 1251 RC Laren, The Netherlands EDITORIAL achievement, recorded only in a scientific journal, "The chess study is close to the chess game was not widely noticed. It was left to the dis- because both study and game obey the same coveries by Ken Thompson of Bell Laboratories rules." This has long been an argument used to in New Jersey, beginning in 1983, to put the boot persuade players to look at studies. Most players m. prefer studies to problems anyway, and readily Aside from a few upsets to endgame theory, the give the affinity with the game as the reason for set of 'total information' 5-raan endgame their preference. Your editor has fought a long databases that Thompson generated over the next battle to maintain the literal truth of that ar- decade demonstrated that several other endings gument. It was one of several motivations in might require well over 50 moves to win. These writing the final chapter of Test Tube Chess discoveries arrived an the scene too fast for FIDE (1972), in which the Laws are separated into to cope with by listing exceptions - which was the BMR (Board+Men+Rules) elements, and G first expedient. Then in 1991 Lewis Stiller and (Game) elements, with studies firmly identified Noam Elkies using a Connection Machine with the BMR realm and not in the G realm. -

Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames

Games of No Chance MSRI Publications Volume 29, 1996 Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames LEWIS STILLER Abstract. This article has three chief aims: (1) To show the wide utility of multilinear algebraic formalism for high-performance computing. (2) To describe an application of this formalism in the analysis of chess endgames, and results obtained thereby that would have been impossible to compute using earlier techniques, including a win requiring a record 243 moves. (3) To contribute to the study of the history of chess endgames, by focusing on the work of Friedrich Amelung (in particular his apparently lost analysis of certain six-piece endgames) and that of Theodor Molien, one of the founders of modern group representation theory and the first person to have systematically numerically analyzed a pawnless endgame. 1. Introduction Parallel and vector architectures can achieve high peak bandwidth, but it can be difficult for the programmer to design algorithms that exploit this bandwidth efficiently. Application performance can depend heavily on unique architecture features that complicate the design of portable code [Szymanski et al. 1994; Stone 1993]. The work reported here is part of a project to explore the extent to which the techniques of multilinear algebra can be used to simplify the design of high- performance parallel and vector algorithms [Johnson et al. 1991]. The approach is this: Define a set of fixed, structured matrices that encode architectural primitives • of the machine, in the sense that left-multiplication of a vector by this matrix is efficient on the target architecture. Formulate the application problem as a matrix multiplication. -

Hypermodern Game of Chess the Hypermodern Game of Chess

The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower Foreword by Hans Ree 2015 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower © Copyright 2015 Jared Becker ISBN: 978-1-941270-30-1 All Rights Reserved No part of this book maybe used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. PO Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Translated from the German by Jared Becker Editorial Consultant Hannes Langrock Cover design by Janel Norris Printed in the United States of America 2 The Hypermodern Game of Chess Table of Contents Foreword by Hans Ree 5 From the Translator 7 Introduction 8 The Three Phases of A Game 10 Alekhine’s Defense 11 Part I – Open Games Spanish Torture 28 Spanish 35 José Raúl Capablanca 39 The Accumulation of Small Advantages 41 Emanuel Lasker 43 The Canticle of the Combination 52 Spanish with 5...Nxe4 56 Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch and Géza Maróczy as Hypermodernists 65 What constitutes a mistake? 76 Spanish Exchange Variation 80 Steinitz Defense 82 The Doctrine of Weaknesses 90 Spanish Three and Four Knights’ Game 95 A Victory of Methodology 95 Efim Bogoljubow -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

Should Chess Players Learn Computer Security?

1 Should Chess Players Learn Computer Security? Gildas Avoine, Cedric´ Lauradoux, Rolando Trujillo-Rasua F Abstract—The main concern of chess referees is to prevent are indeed playing against each other, instead of players from biasing the outcome of the game by either collud- playing against a little girl as one’s would expect. ing or receiving external advice. Preventing third parties from Conway’s work on the chess grandmaster prob- interfering in a game is challenging given that communication lem was pursued and extended to authentication technologies are steadily improved and miniaturized. Chess protocols by Desmedt, Goutier and Bengio [3] in or- actually faces similar threats to those already encountered in der to break the Feige-Fiat-Shamir protocol [4]. The computer security. We describe chess frauds and link them to their analogues in the digital world. Based on these transpo- attack was called mafia fraud, as a reference to the sitions, we advocate for a set of countermeasures to enforce famous Shamir’s claim: “I can go to a mafia-owned fairness in chess. store a million times and they will not be able to misrepresent themselves as me.” Desmedt et al. Index Terms—Security, Chess, Fraud. proved that Shamir was wrong via a simple appli- cation of Conway’s chess grandmaster problem to authentication protocols. Since then, this attack has 1 INTRODUCTION been used in various domains such as contactless Chess still fascinates generations of computer sci- credit cards, electronic passports, vehicle keyless entists. Many great researchers such as John von remote systems, and wireless sensor networks. -

Extended Null-Move Reductions

Extended Null-Move Reductions Omid David-Tabibi1 and Nathan S. Netanyahu1,2 1 Department of Computer Science, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan 52900, Israel [email protected], [email protected] 2 Center for Automation Research, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA [email protected] Abstract. In this paper we review the conventional versions of null- move pruning, and present our enhancements which allow for a deeper search with greater accuracy. While the conventional versions of null- move pruning use reduction values of R ≤ 3, we use an aggressive re- duction value of R = 4 within a verified adaptive configuration which maximizes the benefit from the more aggressive pruning, while limiting its tactical liabilities. Our experimental results using our grandmaster- level chess program, Falcon, show that our null-move reductions (NMR) outperform the conventional methods, with the tactical benefits of the deeper search dominating the deficiencies. Moreover, unlike standard null-move pruning, which fails badly in zugzwang positions, NMR is impervious to zugzwangs. Finally, the implementation of NMR in any program already using null-move pruning requires a modification of only a few lines of code. 1 Introduction Chess programs trying to search the same way humans think by generating “plausible” moves dominated until the mid-1970s. By using extensive chess knowledge at each node, these programs selected a few moves which they consid- ered plausible, and thus pruned large parts of the search tree. However, plausible- move generating programs had serious tactical shortcomings, and as soon as brute-force search programs such as Tech [17] and Chess 4.x [29] managed to reach depths of 5 plies and more, plausible-move generating programs fre- quently lost to brute-force searchers due to their tactical weaknesses. -

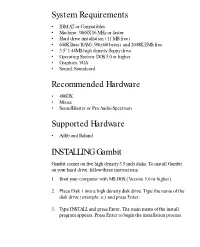

System Requirements Recommended Hardware Supported Hardware

System Requirements • IBM AT or Compatibles • Machine: 386SX 16 MHz or faster • Hard drive installation (11 MB free) • 640K Base RAM (590,000 bytes) and 2048K EMS free • 3.5” 1.44MB high density floppy drive • Operating System: DOS 5.0 or higher • Graphics: VGA • Sound: Soundcard Recommended Hardware • 486DX • Mouse • SoundBlaster or Pro Audio Spectrum Supported Hardware • Adlib and Roland INSTALLING Gambit Gambit comes on five high density 3.5 inch disks. To install Gambit on your hard drive, follow these instructions: 1. Boot your computer with MS-DOS (Version 5.0 or higher). 2. Place Disk 1 into a high density disk drive. Type the name of the disk drive (example: a:) and press Enter. 3. Type INSTALL and press Enter. The main menu of the install program appears. Press Enter to begin the installation process. 4. When Disk 1 has been installed, the program requests Disk 2. Remove Disk 1 from the floppy drive, insert Disk 2, and press Enter. 5. Follow the above process until you have installed all five disks. The Main Menu appears. Select Configure Digital Sound Device from the Main Menu and press Enter. Now choose your sound card by scrolling to it with the highlight bar and pressing Enter. Note: You may have to set the Base Address, IRQ and DMA channel manually by pressing “C” in the Sound Driver Selection menu. After you’ve chosen your card, press Enter. 6. Select Configure Music Sound Device from the Main Menu and press Enter. Now choose your music card by scrolling to it with the highlight bar and pressing Enter.