Yearbook.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1999/6 Layout

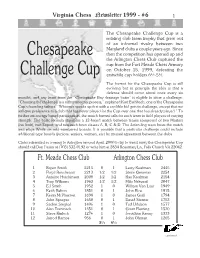

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

Kolov LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS an INVESTMENT in CHESS Po~;T;On No

Vol. Vll Monday; N umber 4 Offjeitll Publication of me Unttecl States (bessTederation October 20, 1952 KOlOV LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS AN INVESTMENT IN CHESS Po~;t;on No. 91 POI;l;"n No. 92 IFE MEMBERSHIP in the USCF is an investment in chess and an Euwe vs. Flohr STILL TOP FIELD L investment for chess. It indicates that its proud holder believes in C.1rIbad, 1932 After fOUl't~n rounds, the S0- chess ns a cause worthy of support, not merely in words but also in viet rcpresentatives still erowd to deeds. For while chess may be a poor man's game in the sense that it gether at the top in the Intel'l'onal does not need or require expensive equipment fm' playing or lavish event at Saltsjobaden. surroundings to add enjoyment to the game, yet the promotion of or· 1. Alexander Kot()v (Russia) .w._.w .... 12-1 ganized chess for the general development of the g'lmc ~ Iway s requires ~: ~ ~~~~(~tu(~~:I;,.i ar ·::::~ ::::::::::~ ~!~t funds. Tournaments cannot be staged without money, teams sent to international matches without funds, collegiate, scholastic and play· ;: t.~h!"'s~~;o il(\~::~~ ry i.. ··::::::::::::ij ); ~.~ ground chess encouraged without the adequate meuns of liupplying ad· 6. Gidcon S tahl ~rc: (Sweden) ...... 81-5l vice, instruction and encouragement. ~: ~,:ct.~.:~bG~~gO~~(t3Ji;Oi· · ·:::: ::::::7i~~ In the past these funds have largely been supplied through the J~: ~~j~hk Elrs'l;~san(A~~;t~~~ ) ::::6i1~ generosity of a few enthusiastic patrons of the game-but no game 11. -

From Los Angeles to Reykjavik

FROM LOS ANGELES CHAPTER 5: TO REYKJAVIK 1963 – 68 In July 1963 Fridrik Ólafsson seized a against Reshevsky in round 10 Fridrik ticipation in a top tournament abroad, Fridrik spent most of the nice opportunity to take part in the admits that he “played some excellent which occured January 1969 in the “First Piatigorsky Cup” tournament in games in this tournament”. Dutch village Wijk aan Zee. five years from 1963 to Los Angeles, a world class event and 1968 in his home town the strongest one in the United States For his 1976 book Fridrik picked only Meanwhile from 1964 the new bian- Reykjavik, with law studies since New York 1927. The new World this one game from the Los Angeles nual Reykjavik chess international gave Champion Tigran Petrosian was a main tournament. We add a few more from valuable playing practice to both their and his family as the main attraction, and all the other seven this special event. For his birthday own chess hero and to the second best priorities. In 1964 his grandmasters had also participated at greetings to Fridrik in “Skák” 2005 Jan home players, plus provided contin- countrymen fortunately the Candidates tournament level. They Timman showed the game against Pal ued attention to chess when Fridrik Benkö from round 6. We will also have Ólafsson competed on home ground started the new biannual gathered in the exclusive Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles for a complete a look at some critical games which against some famous foreign players. international tournament double round event of 14 rounds. -

Montenegro Chess Festival

Montenegro Chess Festival 2 IM & GM Round Robin Tournaments, 26.02-18.03.2021. Festival Schedule: Chess Club "Elektroprivreda" and Montenegro Chess Federation organizing Montenegro Chess Festival from 26th February to 18th March 2021. Festival consists 3 round robin tournaments as follows: 1. IM Round Robin 2021/01 - Niksic 26th February – 4th March 2. IM Round Robin 2021/02 - Niksic 5th March – 11th March 3. GM Round Robin 2021/01 - Podgorica 12th March – 18th March Organizer will provide chess equipment for all events, games will be broadcast online. Winners of all tournaments receive trophy. You can find Information about tournaments on these links: IM Round Robin 2021/01 - https://chess-results.com/tnr549103.aspx?lan=1 IM Round Robin 2021/02 - https://chess-results.com/tnr549104.aspx?lan=1 GM Round Robin 2021/01 - https://chess-results.com/tnr549105.aspx?lan=1 Health protection measures will be applied according to instructions from Montenegro institutions and will be valid during the tournament duration. Masks are obligatory all the time, safe distance will be provided between the boards. Organizer are allowed to cancel some or all events in the festival if situation with pandemic requests events to be cancelled. Tournaments Description: Round Robin tournaments are closed tournaments with 10 participants each and will be valid for international chess title norms. Drawing of lots and Technical Meeting for each event will be held at noon on the starting day of each tournament. Minimal guaranteed average rating of opponents on GM tournament is 2380 and 2230 on IM tournament. Playing schedule: For all three tournaments, double rounds will be played second and third day. -

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

Preparation of Papers for R-ICT 2007

Chess Puzzle Mate in N-Moves Solver with Branch and Bound Algorithm Ryan Ignatius Hadiwijaya / 13511070 Program Studi Teknik Informatika Sekolah Teknik Elektro dan Informatika Institut Teknologi Bandung, Jl. Ganesha 10 Bandung 40132, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract—Chess is popular game played by many people 1. Any player checkmate the opponent. If this occur, in the world. Aside from the normal chess game, there is a then that player will win and the opponent will special board configuration that made chess puzzle. Chess lose. puzzle has special objective, and one of that objective is to 2. Any player resign / give up. If this occur, then that checkmate the opponent within specifically number of moves. To solve that kind of chess puzzle, branch and bound player is lose. algorithm can be used for choosing moves to checkmate the 3. Draw. Draw occur on any of the following case : opponent. With good heuristics, the algorithm will solve a. Stalemate. Stalemate occur when player doesn‟t chess puzzle effectively and efficiently. have any legal moves in his/her turn and his/her king isn‟t in checked. Index Terms—branch and bound, chess, problem solving, b. Both players agree to draw. puzzle. c. There are not enough pieces on the board to force a checkmate. d. Exact same position is repeated 3 times I. INTRODUCTION e. Fifty consecutive moves with neither player has Chess is a board game played between two players on moved a pawn or captured a piece. opposite sides of board containing 64 squares of alternating colors. -

In This Issue

CHESS MOVES The newsletter of the English Chess Federation | 6 issues per year | May/June 2015 John Nunn, Keith Arkell and Mick Stokes at the 15th European Senior Chess Championships - John with his Silver Medal and Keith with his Bronze for the Over 50s section IN THIS ISSUE - ECF News 2-4 Calendar 14-16 Tournament Round-Up 5-6 Supplement --- Junior Chess 6-8 Simon Williams S7 Euro Seniors 9-10 Readers’ Letters S36 National Club 10 Never Mind the GMs S44 Grand Prix 11-12 Home News S52-53 Book Reviews 13 1 ECF NEWS The Chess Trust The Chess Trust has now been approved by the Charity Commission as registered charity no. 1160881. This will be the charitable arm of the ECF with wide ranging charitable purposes to support the provision and development of chess within England. This is good news There is still work to be done to enable the Trust to become operational, which the trustees will address over the next few months. The initial trustees are Ray Edwards, Keith Richardson, Julian Farrand, Phil Ehr and David Eustace. Questions about the Trust can be raised on the ECF Forum at http://www.englishchess.org.uk/Forum/view- topic.php?f=4&t=261 FIDE – ECF meeting report FIDE President Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, ECF President Dominic Lawson and Russian Chess Federation President Andrei Filatov met in London on 11 March 2015. The other ECF participants were Chief Executive Phil Ehr and FIDE Delegate Malcolm Pein. The other FIDE participants were Assistant to the FIDE President Barik Balgabaev and Secretary of FIDE’s Chess in Schools Commission Sainbayar Tserendorj, who is also the founder and ECF Council member for the UK Chess Academy. -

Deconstructing the Myth of Brilliant Attacking Play NEW!

U.S. TEAM TAKES GOLD AT THE WORLD SENIOR October 2018 | USChess.org Deconstructing the Myth of Brilliant Attacking Play NEW! GM Alexander Kalinin traces Fabiano Caruana’s career, analyses the role of his various trainers, explains the development of his playing style and points out what you can learn from his best games. With #!"$ paperback | 208 pages | $19.95 | from the publishers of A Magazine Free Ground Shipping On All Books, Software and DVDs at US Chess Sales $25.00 Minimum - Excludes Clearance, Shopworn and Items Otherwise Marked ADULT $ SCHOLASTIC $ 1 YEAR 49 1 YEAR 25 PREMIUM MEMBERSHIP PREMIUM MEMBERSHIP In addition to these two MEMBER BENEFITS premium categories, US Chess has many •Rated Play for the US Chess community other categories and multi-year memberships •Print and digital copies of Chess Life (or Chess Life Kids) to suit your needs. For all of your options, •Promotional discounts on chess books and equipment see new.uschess.org/join- uschess/ or call •Helping US Chess grow the game 1-800-903-8723, option 4. www.uschess.org 1 Main office: Crossville, TN (931) 787-1234 Press and Communications Inquiries: [email protected] Advertising inquiries: (931) 787-1234, ext. 123 Tournament Life Announcements (TLAs): All TLAs should be e-mailed to [email protected] or sent to P.O. Box 3967, Crossville, TN 38557-3967 Letters to the editor: Please submit to [email protected] Receiving Chess Life: To receive Chess Life as a Premium Member, join US Chess, or enter a US Chess tournament, go to uschess.org or call 1-800-903-USCF (8723) Change of address: Please send to [email protected] Other inquiries: [email protected], (931) 787-1234, fax (931) 787-1200 US CHESS US CHESS STAFF EXECUTIVE Executive Director, Carol Meyer ext. -

Chess Mag - 21 6 10 18/09/2020 14:01 Page 3

01-01 Cover - October 2020_Layout 1 18/09/2020 14:00 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/09/2020 14:01 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Peter Wells.......................................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine The acclaimed author, coach and GM still very much likes to play Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Website: www.chess.co.uk Online Drama .........................................................................................................8 Danny Gormally presents some highlights of the vast Online Olympiad Subscription Rates: United Kingdom Carlsen Prevails - Just ....................................................................................14 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Nakamura pushed Magnus all the way in the final of his own Tour 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 Find the Winning Moves.................................................................................18 3 year (36 issues) £125 Can you do as well as the acclaimed field in the Legends of Chess? Europe 1 year (12 issues) £60 Opening Surprises ............................................................................................22 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 -

April 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT

Volume 48, Number 2 COLORADO STATE CHESS ASSOCIATION April 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT COLORADO SCHOLASTIC ONLINE CHAMPIONSHIP Volume 48, Number 2 Colorado Chess Informant April 2021 From the Editor With measured steps, the Colorado chess scene may just be com- ing back to life. It has been announced that the Colorado Open has been sched- uled for Labor Day weekend this year - albeit with safety proto- cols in place. Be sure to check out the website as the date nears (www.ColoradoChess.com) because as we are aware, things The Colorado State Chess Association, Incorporated, is a could change. The Denver Chess Club has also announced a Section 501(C)(3) tax exempt, non-profit educational corpora- tournament in June of this year - go to their website tion formed to promote chess in Colorado. Contributions are (www.DenverChess.com) for more information on that one. tax deductible. It is with a heavy heart and profound sadness that a friend and Dues are $15 a year. Youth (under 20) and Senior (65 or older) ‘chess bud’ of mine has passed away. Not long after his 70th memberships are $10. Family memberships are available to birthday in January, Michael Wokurka collapsed at his home on additional family members for $3 off the regular dues. Scholas- the 22nd - and never regained consciousness. No prior warning tic tournament membership is available for $3. or health issues were known. His obituary online is listed here: ● Send address changes to - Attn: Alexander Freeman to the https://tinyurl.com/2rz9zrca. He loved the game of chess, and email address [email protected]. -

Bulletin #251

BCCF E-MAIL BULLETIN #251 Your editor welcomes any and all submissions - news of upcoming events, tournament reports, and anything else that might be of interest to B.C. players. Thanks to all who contributed to this issue. To subscribe, send me an e-mail ([email protected]) or sign up via the BCCF webpage (www.chess.bc.ca); if you no longer wish to receive this Bulletin, just let me know. Stephen Wright HERE AND THERE EAC Chess Arts Open #16 (October 27-28) The latest open tournament organized, directed, and hosted by Eugenio Alonso Campos attracted a total of five players, thus a round robin was held. After some sub-par performances of late Peter Yee came out on top, taking clear first with 3.5/4. His draw was with Eugenio Alonso Campos, who gave up another draw to tail-ender Constantin Rotariu in finishing second. Ashley Tapp was third and achieved her best performance rating to date. Crosstable 16th Unive Chess Festival (October 19-27) Held in Hoogeveen (the Netherlands), the festival consisted of a Crown Group, an Open, and a couple of amateur events. The Crown Group, a four-player double round robin, was headed by sometime BC resident Hikaru Nakamura. Nakamura has had a rocky time in his last few events but took first here with 4.5/6, ahead of Sergei Tiviakov, Anish Giri, and Women’s World Champion Yifan Hou. The other main event was the Open, a nine-round tournament which attracted seventy- eight players, including BC’s Leon Piasetski. All the top places were taken by Dutch players: Erwin L’Ami and Friso Nijboer tied for first with 7.0/9, while Sipke Ernst, veteran Jan Timman, Robin van Kampen, and Manuel Bosboom all finished with 6.5 points. -

Should Chess Players Learn Computer Security?

1 Should Chess Players Learn Computer Security? Gildas Avoine, Cedric´ Lauradoux, Rolando Trujillo-Rasua F Abstract—The main concern of chess referees is to prevent are indeed playing against each other, instead of players from biasing the outcome of the game by either collud- playing against a little girl as one’s would expect. ing or receiving external advice. Preventing third parties from Conway’s work on the chess grandmaster prob- interfering in a game is challenging given that communication lem was pursued and extended to authentication technologies are steadily improved and miniaturized. Chess protocols by Desmedt, Goutier and Bengio [3] in or- actually faces similar threats to those already encountered in der to break the Feige-Fiat-Shamir protocol [4]. The computer security. We describe chess frauds and link them to their analogues in the digital world. Based on these transpo- attack was called mafia fraud, as a reference to the sitions, we advocate for a set of countermeasures to enforce famous Shamir’s claim: “I can go to a mafia-owned fairness in chess. store a million times and they will not be able to misrepresent themselves as me.” Desmedt et al. Index Terms—Security, Chess, Fraud. proved that Shamir was wrong via a simple appli- cation of Conway’s chess grandmaster problem to authentication protocols. Since then, this attack has 1 INTRODUCTION been used in various domains such as contactless Chess still fascinates generations of computer sci- credit cards, electronic passports, vehicle keyless entists. Many great researchers such as John von remote systems, and wireless sensor networks.