Chess Moves.Qxp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65 COMPUTER ANALYSIS OF WORLD CHESS CHAMPIONS1 Matej Guid2 and Ivan Bratko2 Ljubljana, Slovenia ABSTRACT Who is the best chess player of all time? Chess players are often interested in this question that has never been answered authoritatively, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. In this contribution, we attempt to make such a comparison. It is based on the evaluation of the games played by the World Chess Champions in their championship matches. The evaluation is performed by the chess-playing program CRAFTY. For this purpose we slightly adapted CRAFTY. Our analysis takes into account the differences in players' styles to compensate the fact that calm positional players in their typical games have less chance to commit gross tactical errors than aggressive tactical players. Therefore, we designed a method to assess the difculty of positions. Some of the results of this computer analysis might be quite surprising. Overall, the results can be nicely interpreted by a chess expert. 1. INTRODUCTION Who is the best chess player of all time? This is a frequently posed and interesting question, to which there is no well founded, objective answer, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. With the emergence of high-quality chess programs a possibility of such an objective comparison arises. However, so far computers were mostly used as a tool for statistical analysis of the players' results. Such statistical analyses often do neither reect the true strengths of the players, nor do they reect their quality of play. -

Business Plan 2009/2010

English Chess Federation BUSINESS PLAN FOR 2009-2010 ECF Mission Statement „To promote the game of chess, in all its forms, as an attractive means of cultural and personal advancement. To foster the highest level of achievement in the game. To make the Federation‟s services and membership available to all, without restriction; and to promote equal opportunities in a positive manner.‟ The Objects of the English Chess Federation [“the Company”] are: To encourage the study and practice of chess in England and for the purpose of these objects England shall be deemed to include such part of North Wales as is within the jurisdiction of the Cheshire & North Wales Chess Association for so long as it shall so remain. To institute and maintain British Chess Championships. To promote national and international chess tournaments in England. To secure the interests of English players (being those players who are entitled to represent England under the statutes and regulations of Fédération Internationale des Echecs [FIDE] for the time being in force) in foreign chess tournaments and matches. To support the Braille Chess Association and other chess organisations which are members of the Company and whose jurisdiction includes England unless and until in each such case separate equivalent English organisations shall be established which are members of the Company. To secure the interests of English problemists in foreign tournaments and tourneys and to encourage English problem composers and solvers by instituting tournaments and tourneys and for these purposes support of the British Chess Problem Society shall be within the scope of this object unless and until a separate English Chess Problem Society shall be established which is a member of the Company. -

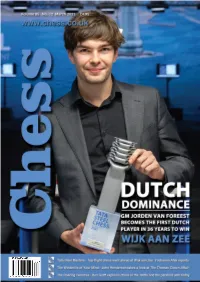

Sample Pages

01-01 Cover -March 2021_Layout 1 17/02/2021 17:19 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/02/2021 09:47 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Jorden van Foreest.......................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine We catch up with the man of the moment after Wijk aan Zee Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Website: www.chess.co.uk Dutch Dominance.................................................................................................8 The Tata Steel Masters went ahead. Yochanan Afek reports Subscription Rates: United Kingdom How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................18 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Daniel King presents one of the games of Wijk,Wojtaszek-Caruana 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 3 year (36 issues) £125 Up in the Air ........................................................................................................21 Europe There’s been drama aplenty in the Champions Chess Tour 1 year (12 issues) £60 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 Howell’s Hastings Haul ...................................................................................24 3 year (36 issues) £165 David Howell ran -

Anything but Average Chess Classics and Off-Beat Problems by Chris Jones

06/140 Book review Werner Keym: Anything but Average Chess Classics and Off-beat Problems By Chris Jones Werner Keym’s book ‘Anything but Average – Chess Classics and Off-beat Problems’ was published in Goettingen (Germany) earlier this year. On 198 pages, it has 375 games, studies, problems, puzzles by 240 authors, 120 related problems, 180 additional diagrams. And it’s in English! For details see <http://www.berlinthema.de> and www.nightrider-unlimited.de. This is a book to gladden the hearts of all chess lovers, even those who usually have little or no interest in composed chess positions. A large part of the book is devoted to ‘The Classics’, beginning with classic games and then going on to classic studies and classic problems. The emphasis is on crowd-pleasers. Amongst the famous (and some not so famous) problems there are some sensational, unexpected key moves, and a lot of surprising and paradoxical continuations. You will pick Amongst the famous up some strategic concepts of problem (and some not so famous) composers along the way, but the emphasis problems there are some is on entertainment rather than instruction. (Often a really surprising move in a sensational, unexpected key solution leads you into exploring why this moves, and a lot of surprising move is the only way to achieve the aim of and paradoxical continuations the problem, and gaining an understanding of problems in this auto-didactic fashion is much the most enjoyable way!) There are also sections on ‘Special Moves’ and ‘Problems Out of the Box’, which The text is very readable (in excellent show how composers have exercised their English), and in studies and longer ingenuity to seek out optimal achievements problems liberally sprinkled with diagrams in showing promotions, e.p. -

Mind-Bending Analysis and Instructive Comment from a Man Who Has Participated in World Chess at the Very Highest Levels

Mind-bending analysis and instructive comment from a man who has participated in world chess at the very highest levels World championship candidate and three-times British Champion Jon Speelman annotates the best of his games. He is renowned as a great fighter and analyst, and a highly original player. This book provides entertainment and instruction in abundance. Games and stories from his: • World Championship campaigns • Chess Olympiads • Toi>level grandmaster tournaments, including the World Cup Jon Speelman is one of only two British players this century to gain a place in the world's top five. He has reached the sem>finals of the world championship and is one of the stars of the English national team, which has won the silver medals three times in the chess Olympiads. Jon Speelman's Best Games Jon Speelman B. T. Batsford Ltd, London First published 1997 © Jon Speelman 1997 ISBN 0 7134 6477 I British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. Contents A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, by any means, without prior permission of the publisher. Introduction 5 Typeset and edited by First Rank Publishing, Brighton and printed in Great Britain by Redwood Books, Trowbridge, Wilts Part I Growing up as a Chess player for the publishers, B. T. Batsford Ltd, Juvenilia 7 583 Fulham Road, I JS-J.Fletcher, British U-14 Ch., Rhyl1969 9 London SW6 5BY 2 JS-E.Warren, Thames Valley Open 1970 11 3 A.Miles-JS, Islington Open 1970 14 4 JS-Hanau, Nice 1971 -

Es Nouvelles Du Championnat Belle Démonstration De Son Envie D'en Découdre

86e championnat de France d’échecs Au fil des rondes... EN PISTE... Ils sont quatre à se détacher, avec une demi-longueur d'avance, au terme de cette 2e journée du National : Laurent Fressinet, Etienne Bacrot, Hicham Hamdouchi et Maxime Vachier-Lagrave. Comme la veille, la deuxième ronde s'est achevée sur 2 résultats décisifs et quatre parties nulles. Si trois de ces dernières affichaient une volonté de ne pas trop forcer "entre amis" et se sont donc conclues rapidement, ce n'était pas le cas de la partie qui a opposé Emmanuel Bricard à Laurent Fressinet, et qui a tenu en haleine les spectateurs de l’amphithéâtre et de la salle de commentaires au "Chess Café". Il est probable que le champion de France 2010 a raté plusieurs opportunités : notamment, selon lui, il fallait jouer 23… Rf7 au lieu de 23…Txc8. Ce qui est certain, c'est qu'Emmanuel Bricard, un joueur pas facile à affronter et atypique, a su saisir ses meilleures chan- ces pour arracher la nulle, comme hier face à Shchekachev. Dans sa partie contre Andreï Shchekachev, Etienne Bacrot a offert au public une es nouvelles du championnat belle démonstration de son envie d'en découdre. Au sortir de l'ouverture, le sex- Bricard-Fressinet tuple champion de France n'avait pas obtenu grand- L Position après 23.Tc8+ chose. Mais la situation allait changer après qu'Etienne ait joué 18. f4 qui lui donnait beaucoup de jeu. Trois coups plus tard (21.f5!!), le Marseillais concrétisait son avantage par un sacrifice de Cavalier qui lui ouvrait les lignes sur le Roi adverse. -

In This Issue

CHESS MOVES The newsletter of the English Chess Federation | 6 issues per year | May/June 2015 John Nunn, Keith Arkell and Mick Stokes at the 15th European Senior Chess Championships - John with his Silver Medal and Keith with his Bronze for the Over 50s section IN THIS ISSUE - ECF News 2-4 Calendar 14-16 Tournament Round-Up 5-6 Supplement --- Junior Chess 6-8 Simon Williams S7 Euro Seniors 9-10 Readers’ Letters S36 National Club 10 Never Mind the GMs S44 Grand Prix 11-12 Home News S52-53 Book Reviews 13 1 ECF NEWS The Chess Trust The Chess Trust has now been approved by the Charity Commission as registered charity no. 1160881. This will be the charitable arm of the ECF with wide ranging charitable purposes to support the provision and development of chess within England. This is good news There is still work to be done to enable the Trust to become operational, which the trustees will address over the next few months. The initial trustees are Ray Edwards, Keith Richardson, Julian Farrand, Phil Ehr and David Eustace. Questions about the Trust can be raised on the ECF Forum at http://www.englishchess.org.uk/Forum/view- topic.php?f=4&t=261 FIDE – ECF meeting report FIDE President Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, ECF President Dominic Lawson and Russian Chess Federation President Andrei Filatov met in London on 11 March 2015. The other ECF participants were Chief Executive Phil Ehr and FIDE Delegate Malcolm Pein. The other FIDE participants were Assistant to the FIDE President Barik Balgabaev and Secretary of FIDE’s Chess in Schools Commission Sainbayar Tserendorj, who is also the founder and ECF Council member for the UK Chess Academy. -

Bulletin 2012 2 FINAL.Indd

Bulletin TAS CAS Bulletin 2 / 2012 Table des matières / Table of contents Message du Président du CIAS / Message of the ICAS President Message of the ICAS President ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Articles et commentaires / Articles and commentaries When is a “Swiss ” “award ” appealable ? ................................................................................................................................... 2 Dr. Charles Poncet La preuve du dopage dans les cas de présence d’une substance interdite ....................................................................... 15 Me Estelle de La Rochefoucauld, Conseiller auprès du TAS Jurisprudence majeure / Leading cases Arbitration CAS 2011/A/2360 & CAS 2011/A/2392 .........................................................................................................26 English Chess Federation & Georgian Chess Federation v. Fédération Internationale des Echecs (FIDE) 3 July 2012 Arbitration CAS 2011/A/2425 ................................................................................................................................................ 33 Ahongalu Fusimalohi v. Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) 8 March 2012 Arbitration CAS 2011/A/2563 ...............................................................................................................................................50 CD Nacional v. FK Sutjeska 30 March 2012 Arbitrage TAS -

January 2016

$3.95 January 2016 Volume 70-1, Northwest Chess enters its 70th year!! Northwest Chess January 2016, Volume 70-1 Issue 816 Table of Contents ISSN Publication 0146-6941 Published monthly by the Northwest Chess Board. Ian Cavey at the Boise Chess Club by Jeffrey Roland..............Front Cover Office of record: c/o Orlov Chess Academy, 2501 152nd Ave NE STE M16, Redmond, WA 98052-5546. Idaho Chess News...............................................................................................3 POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: Oregon Chess News...........................................................................................9 Northwest Chess c/o Orlov Chess Academy, 2501 Washington Chess News....................................................................................18 152nd Ave NE STE M16, Redmond, WA 98052-5546. Chess Groovies by NM Daniel He and NM Samuel He...............................26 Periodicals Postage Paid at Seattle, WA Northwest Chess Grand Prix by Murlin Varner............................................28 USPS periodicals postage permit number (0422-390) Seattle Chess Club Tournaments....................................................................30 NWC Staff Upcoming Events...............................................................................................31 Editor: Jeffrey Roland, [email protected] Roland Feng and Nick Raptis at the State Champions Match by Josh Games Editor: Ralph Dubisch, Sinanan...............................................................................................Back -

United States Chess Federation How Many Variations?

UNITED STATES CHESS FEDERATION , ( I -• -I USCF .J •- .J America's Chess Periodical Volume XVI. Number 9 SEPTEMBER, \961 40 Cents HOW MANY VARIATIONS? 169,518,829,100,544,000,000,000,000,000 X 700 (See ~II. 253) REPORT FROM FIDE At tile ' CCClll 1'10£ COllgrefl heW at night, Mr. Hellimo has put forward the Leipzig, GrunJmmtcr M ilora V/(fmtlr 0/ Yu· original proposition to adjourn the game gruiall/6 fIIbcd mallll qlll!lIiOW} all to ,1M for a pause of 2 hours already after I adutsabilily of .Wltg lectmru In malor chaA first period of only 2 hour::, in view of event, aru:i Ille ".0. and co"", of Immlllll.re the lact that in its initial phase a game draWl by agreemlm' . J\/1 of tlw member ollcrs much less chances [or an effective C(JImlr/c1 0/ FIDE were poUcd 01 10 I/urlr analysis than later on. wcleu;JIC(!J 1111(/ idCf/iI all t/1e5e 111."0 (I I.e,· Among the federalions and persons litms and foffowllIg I.J Iflc $rUllIIllJry: who have recommended an organization of play allowing a great number or Summary of the resulh of the Inquiry on gumcs to be terminated in the sa me day the questions r.iHd by Grand-MlSler as they have been begun, certain have Vidmar. lironounced themselves in lavour of a The questions raised by Grand·Master lengthening of the [irs!: period ol play. Vidmar have aroused a rather vivid in while others wish to keep the duration terest and the number of answers pre. -

British Knockout: Adams, Howell, Jones & Mcshane

PRESS RELEASE For immediate release BRITISH KNOCKOUT: ADAMS, HOWELL, JONES & MCSHANE INTO SEMIS England top 4 Mickey Adams, David Howell, Gawain Jones and Luke McShane all negotiate their way through a tough quarter-final stage to qualify for the British Knockout Championship semi-finals. David Howell triumphs eventually over IM Ravi Haria in a rapid playoff, despite almost coming to grief in the first Classical game. Semi-Finals pit Adams vs McShane and Howell vs Jones. Live coverage of the Semi-Final matches, starting Tuesday at 11:00 UTC, is available on the London Chess Classic website. LONDON (December 10, 2018) – Despite valiant efforts from the underdogs in the British Knockout, England Olympiad team members Mickey Adams, David Howell, Gawain Jones and Luke McShane all managed to win their Quarter-Final matches – although not without a struggle. Qtr Fina1 1 1 2 3 4 A Simon Williams 2466 ½ 0 - - - ½ Mickey Adams 2706 ½ 1 - - - 1½ Qtr Fina1 2 1 2 3 4 A David Howell 2697 ½ ½ 1 1 - 3 Ravi Haria 2436 ½ ½ 0 0 - 1 Qtr Fina1 3 1 2 3 4 A Gawain Jones 2683 1 ½ - - - 1½ Alan Merry 2429 0 ½ - - - ½ Qtr Fina1 4 1 2 3 4 A Jonathan Hawkins 2579 ½ 0 - - - ½ Luke McShane 2667 ½ 1 - - - 1½ David Howell had the closest shave of all the top seeds, only managing to qualify for the Semi-Finals after winning a nail-biting playoff match 2-0 against IM Ravi Haria. Elsewhere, Mickey Adams enjoyed a convincing victory in Game 2 of his match, after putting GM Simon Williams’s central king position under pressure in a double-edged Sicilian Richter-Rauzer. -

Chess-Training-Guide.Pdf

Q Chess Training Guide K for Teachers and Parents Created by Grandmaster Susan Polgar U.S. Chess Hall of Fame Inductee President and Founder of the Susan Polgar Foundation Director of SPICE (Susan Polgar Institute for Chess Excellence) at Webster University FIDE Senior Chess Trainer 2006 Women’s World Chess Cup Champion Winner of 4 Women’s World Chess Championships The only World Champion in history to win the Triple-Crown (Blitz, Rapid and Classical) 12 Olympic Medals (5 Gold, 4 Silver, 3 Bronze) 3-time US Open Blitz Champion #1 ranked woman player in the United States Ranked #1 in the world at age 15 and in the top 3 for about 25 consecutive years 1st woman in history to qualify for the Men’s World Championship 1st woman in history to earn the Grandmaster title 1st woman in history to coach a Men's Division I team to 7 consecutive Final Four Championships 1st woman in history to coach the #1 ranked Men's Division I team in the nation pnlrqk KQRLNP Get Smart! Play Chess! www.ChessDailyNews.com www.twitter.com/SusanPolgar www.facebook.com/SusanPolgarChess www.instagram.com/SusanPolgarChess www.SusanPolgar.com www.SusanPolgarFoundation.org SPF Chess Training Program for Teachers © Page 1 7/2/2019 Lesson 1 Lesson goals: Excite kids about the fun game of chess Relate the cool history of chess Incorporate chess with education: Learning about India and Persia Incorporate chess with education: Learning about the chess board and its coordinates Who invented chess and why? Talk about India / Persia – connects to Geography Tell the story of “seed”.