The Nemesis Efim Geller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chess Viewer the Power of XSL Lies in Its Ability to Perform Radical Transformations of the XML Data Source

DEVELOPER'S ZONE SHOP SEARCH Products Demos Stories Solutions Support Download Customers Partners Company Sitemap Chess Viewer The power of XSL lies in its ability to perform radical transformations of the XML data source. This page contains yet another proof for this fact: you can build a chessgame viewer with a stylesheet! The source document is a transcription of a chess game played by Garry Kasparov against a chess supercomputer -- IBM Deep Blue. The game is encoded in a form resembling the well-known Portable Game Notation (PGN) format. The source is very compact: a sample game on this page [DeepBlue.xml] is less than 4 kBytes in size. The stylesheet converts this arid text into a sequence of board diagrams, drawing every intermediate position as a graphical image (a special chess font is used). Applying a 23 kB stylesheet [chess.xsl], we get a 415 kBytes (!) FO stream [DeepBlue.fo]. These numbers give an idea of how deep the transformation is. The final step of the whole procedure consists in converting the result into PDF using XEP. The resulting PDF file [DeepBlue.pdf] is much smaller than the source FO stream -- less than 90 kBytes. (XEP implements PDF compression). We hope XSL fans will enjoy this example; and XSL foes will acknowledge its power! More chess games created by the same stylesheet: Description FO Source PDF PostScript Fischer-Euwe.xml Fischer-Euwe.fo Fischer-Euwe.pdf Fischer-Euwe.ps Robert Fischer - Max Euwe Fischer-Tal.xml Fischer-Tal.fo Fischer-Tal.pdf Fischer-Tal.ps Robert Fischer - Mikhail Tal Kasparov-Karpov.xml Kasparov-Karpov.fo Kasparov-Karpov.pdf Kasparov-Karpov.ps Garry Kasparov - Anatoly Karpov Note: We have used an unabridged chess notation; the original PGN data are even more concise.We know it is possible to process even the short chess notation by XSL, and gladly leave this exercise to volunteers . -

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

An Interview with FIDE GM Mikhail Golubev by Santhosh Matthew Paul Copyright 2001 by Santhosh Matthew Paul, All Rights Reserved

Correspondence Chess News Issue 31 - 14 January 2001 An Interview with FIDE GM Mikhail Golubev By Santhosh Matthew Paul Copyright 2001 by Santhosh Matthew Paul, All rights reserved. How did you first get attracted to chess? Please also say something about your early chess development in Ukraine. I started to play in 1976 (at the age of six) and from 1977 onwards, I started to learn chess in the chess club (by the way, many players the world over think that chess was an obligatory discipline in the regular Soviet Schools – that’s not correct). Sometimes, I think that I started to look at chess seriously after my parents got divorced, but I’m not sure if it was the real impetus. In any case, I was quite able to play chess. It is easy to say as I scored many good results, especially at the age of 12-14 years. For instance, in the 1984 (at age 14), I shared second place (with the better tiebreak) with Ivanchuk (he was one year older) in the Ukrainian Junior Ch U- 17. Still, I’m not sure if I’m a born chess player. I remember, in 1984 I played in a junior tournament in Baku, and shared the first place there with Vladimir Akopian. Volodya is one year younger than me, and he was very small in 1984 J . We played an extremely complicated game, and I accepted his draw offer when my position was already better. I was quite afraid for him, as for the first time I saw a clearly more talented player than me. -

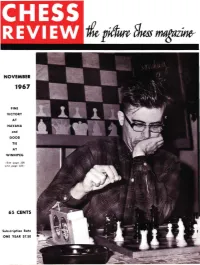

CR1967 11.Pdf

NOVEMBER 1967 FINE VICTORY AT HAVANA and GOOD TIE AT WINNIPEG ( Set PllO" ) 2$ .:ond pig" 323) 65 CENTS Subscription Rat. ONE YEAR 57.50 e wn 789 7 'h by 9 Inches. clothbound 221 diagrams 493 idea Yariations 1704 practical yariations 463 supplementary variations 3894 notes to all yariations and 439 COMPLETE GAMES! BY I. A . HOROWITZ in collaboration with Former World Champion, Dr. Max Euwe. Ernest Gruenfeld, Hans Kmoch. and many other noted authorities This latest Hild immense work, the most exhaustive of its kind, ex· plains in encyclopedic detail the fine points of all openings. It carries the reader well into the middle game, evaluates the prospects there and often gives complete exemplary games so that he is not left hanging in mid.position with the query: What happens now? A logical sequence binds the continuity in each opening. First come the moves with footnotes leading to the key positi on. Then fol· BIBLIOPHILES! low pertinent observations, illustrated by " Idea Variations." Finally, Glossy paper, handsome print, Practical and Supplementary Va riations, well annotated, exemplify the spaciolls paging and all the effective po::isibilities. Each line is appraised: +. - or =. The hi rge format- 71f2 x 9 inches-is designed for ease of read· other appurtenances of exqllis ing and playing. It eliminates much tiresome shuIIling of pages ite book-making combine to between the principal Jines and the respective comments. Clear, make this the handsomest of legible type, a wide margin for inserting notes and variation-identify. ing diagrams are olher plus features. chess books! In addition to all else. -

Schachweltmeister (Wikipedia)

Schachweltmeister weltmeister“ wurden in Abgrenzung zur separa- ten Schachweltmeisterschaft der Frauen historisch auch als „Schachweltmeisterschaft der Männer“ be- zeichnet. Seit einer entsprechenden Klärung in den späten 1980ern steht der Titel aber generell Män- nern und Frauen offen. Beschränkt für Altersstu- fen gibt es die Juniorenweltmeisterschaft (U20), die Jugendweltmeisterschaften in den Altersklassen U8–U18 und die Seniorenweltmeisterschaft – alle ebenfalls offen für beide Geschlechter, aber auch mit eigenen Bewerben für Spielerinnen. Dazu gibt es Weltmeisterschaften im Blitzschach, Schnellschach und Fernschach. Weltmeisterschaften werden als Zweikampf über mehre- re Partien zwischen dem Weltmeister und einem Heraus- forderer ausgetragen. In den Jahren 1948 und 2007 er- mittelte man den Weltmeister dagegen durch ein Run- denturnier mit mehreren Teilnehmern. Der Herausfor- derer muss sich üblicherweise durch den Gewinn des Kandidatenturniers für den WM-Zweikampf qualifizie- ren. Eine zwischenzeitliche Trennung des Weltmeistertitels vom Weltverband FIDE seit 1993 wurde 2006 durch die Schachweltmeisterschaft 2006 behoben. Während dieser Zeit führte die FIDE Weltmeisterschaften durch, deren Sieger jedoch nicht als allgemein anerkannte Weltmeis- ter galten. 1 Die weltbesten Spieler vor Ein- führung der offiziellen Weltmeis- Oben: Logo des Weltschachbundes FIDE terschaftskämpfe Mitte: Weltmeister Michail Botwinnik 0000und Wilhelm Steinitz Unten: Schachweltmeisterschaft 2008 Der Titel Schachweltmeister ist die höchste Aus- zeichnung im Schachspiel, die – in der Regel – nach vorausgehenden Qualifikationsturnieren und schließlich durch einen Zweikampf um die Schachweltmeisterschaft vergeben wird. Als erster offizieller Schachweltmeis- ter gilt der Österreicher Wilhelm Steinitz nach sei- nem Wettkampfsieg gegen Johannes Hermann Zukert- ort im Jahr 1886. Amtierender Weltmeister ist seit 2013 der Norweger Magnus Carlsen, der den Titel bei der Erstes internationales Schachturnier am Hofe König Philipps II. -

A Feast of Chess in Time of Plague – Candidates Tournament 2020

A FEAST OF CHESS IN TIME OF PLAGUE CANDIDATES TOURNAMENT 2020 Part 1 — Yekaterinburg by Vladimir Tukmakov www.thinkerspublishing.com Managing Editor Romain Edouard Assistant Editor Daniël Vanheirzeele Translator Izyaslav Koza Proofreader Bob Holliman Graphic Artist Philippe Tonnard Cover design Mieke Mertens Typesetting i-Press ‹www.i-press.pl› First edition 2020 by Th inkers Publishing A Feast of Chess in Time of Plague. Candidates Tournament 2020. Part 1 — Yekaterinburg Copyright © 2020 Vladimir Tukmakov All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. ISBN 978-94-9251-092-1 D/2020/13730/26 All sales or enquiries should be directed to Th inkers Publishing, 9850 Landegem, Belgium. e-mail: [email protected] website: www.thinkerspublishing.com TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY TO SYMBOLS 5 INTRODUCTION 7 PRELUDE 11 THE PLAY Round 1 21 Round 2 44 Round 3 61 Round 4 80 Round 5 94 Round 6 110 Round 7 127 Final — Round 8 141 UNEXPECTED CONCLUSION 143 INTERIM RESULTS 147 KEY TO SYMBOLS ! a good move ?a weak move !! an excellent move ?? a blunder !? an interesting move ?! a dubious move only move =equality unclear position with compensation for the sacrifi ced material White stands slightly better Black stands slightly better White has a serious advantage Black has a serious advantage +– White has a decisive advantage –+ Black has a decisive advantage with an attack with initiative with counterplay with the idea of better is worse is Nnovelty +check #mate INTRODUCTION In the middle of the last century tournament compilations were ex- tremely popular. -

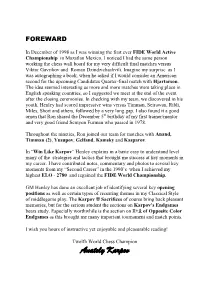

Anatoly Karpov INTRODUCTION

FOREWARD In December of 1998 as I was winning the first ever FIDE World Active Championship in Mazatlan Mexico, I noticed I had the same person working the chess wall board for my very difficult final matches versus Viktor Gavrikov and Roman Dzindzichashvili. Imagine my surprise as I was autographing a book, when he asked if I would consider an American second for the upcoming Candidates Quarter-final match with Hjartarson. The idea seemed interesting as more and more matches were taking place in English speaking countries, so I suggested we meet at the end of the event after the closing ceremonies. In checking with my team, we discovered in his youth, Henley had scored impressive wins versus Timman, Seirawan, Ribli, Miles, Short and others, followed by a very long gap. I also found it a good omen that Ron shared the December 5th birthday of my first trainer/mentor and very good friend Semyon Furman who passed in 1978. Throughout the nineties, Ron joined our team for matches with Anand, Timman (2), Yusupov, Gelfand, Kamsky and Kasparov. In “Win Like Karpov” Henley explains in a basic easy to understand level many of the strategies and tactics that brought me success at key moments in my career. I have contributed notes, commentary and photos to several key moments from my “Second Career” in the 1990’s when I achieved my highest ELO - 2780 and regained the FIDE World Championship. GM Henley has done an excellent job of identifying several key opening positions as well as certain types of recurring themes in my Classical Style of middlegame play. -

A Glimpse Into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer July 24, 2014 – June 7, 2015

Media Contact: Amanda Cook [email protected] 314-598-0544 A Memorable Life: A Glimpse into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer July 24, 2014 – June 7, 2015 July XX, 2014 (Saint Louis, MO) – From his earliest years as a child prodigy to becoming the only player ever to achieve a perfect score in the U.S. Chess Championships, from winning the World Championship in 1972 against Boris Spassky to living out a controversial retirement, Bobby Fischer stands as one of chess’s most complicated and compelling figures. A Memorable Life: A Glimpse into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer opens July 24, 2014, at the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) and will celebrate Fischer’s incredible career while examining his singular intellect. The show runs through June 7, 2015. “We are thrilled to showcase many never-before-seen artifacts that capture Fischer’s career in a unique way. Those who study chess will have the rare opportunity to learn from his notes and books while casual fans will enjoy exploring this superstar’s personal story,” said WCHOF Chief Curator Bobby Fischer, seen from above, Shannon Bailey. makes a move during the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup. Several of the rarest pieces on display are on generous loan from Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield, owners of a a collection of material from Fischer’s own library that includes 320 books and 400 periodicals. These items supplement highlights from WCHOF’s permanent collection to create a spectacular show. Highlights from the exhibition: Furniture from the home of Fischer’s mentor Jack Collins, which -

Honours Thesis Game Theory and the Metaphor of Chess in the Late Cold

Honours Thesis Game Theory and the Metaphor of Chess in the late Cold War Period o Student number: 6206468 o Home address: Valeriaan 8 3417 RR Montfoort o Email address: [email protected] o Type of thesis/paper: Honours Thesis o Submission date: March 29, 2020 o Thesis supervisor: Irina Marin ([email protected]) o Number of words: 18.291 o Page numbers: 55 Abstract This thesis discusses how the game of chess has been used as a metaphor for the power politics between the United States of America and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, particularly the period of the Reagan Doctrine (1985-1989). By looking at chess in relation to its visual, symbolic and political meanings, as well in relation to game theory and the key concepts of polarity and power politics, it argues that, although the ‘chess game metaphor’ has been used during the Cold War as a presentation for the international relations between the two superpowers in both cultural and political endeavors, the allegory obscures many nuances of the Cold War. Acknowledgment This thesis has been written roughly from November 2019 to March 2020. It was a long journey, and in the end my own ambition and enthusiasm got the better of me. The fact that I did three other courses at the same time can partly be attributed to this, but in many ways, I should have kept my time-management and planning more in check. Despite this, I enjoyed every moment of writing this thesis, and the subject is still captivating to me. -

Conference Program

9th World Energy System Conference The 9th WORLD ENERGY SYSTEM CONFERENCE WESC 2012 June 28-30, 2012 Suceava – Romania http://www.wesc.usv.ro Conference program Organized by „Ştefan cel Mare” University of Suceava Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science E-ON Moldova AGIR Romania ASTR Romania CIGRE Romania TRANSELECTRICA Romania OPCOM Romania LOIAL Suceava LIONS Suceava 9th World Energy System Conference HONORARY CHAIR Prof. Adrian GRAUR, „Ştefan cel Mare” University of Suceava, Romania CONFERENCE Co-CHAIRs Prof. Radu PENTIUC, „Ştefan cel Mare” University of Suceava, Romania Prof. Gianfranco CHICCO, Politecnico di Torino, Italy Eng. Puica NITU, PEO Canada Acad. Nikolai VOROPAI, ESI, Irkutsk, Russia Prof. Vladimiro MIRANDA, Portugal Prof. Petru ANDEA, „Politehnica” University of Timişoara, Romania Prof. Sorin PAVEL, Technical University of Cluj-Napoca, Romania Prof. Petru POSTOLACHE, „Politehnica” University of Bucharest, Romania Eng. Livioara ŞUJDEA, Director E-ON Romania Prof. Florin TĂNĂSESCU, The Academy of Technical Sciences of Romania INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC CONFERENCE COMMITTEE Prof. Tudor AMBROS, Technical University of Moldovia, Chişinău Prof. Petru ANDEA, Politechnica University of Timişoara, Romania Prof. Horia ANDREI, Valahia University of Târgoviste, Romania Prof. Rachid BACHTRI, University of Fes, Maroc Dr. Mohammad BARAKAT, Al Balka University Amman, Jordan Prof. Gheorghe BĂLUŢĂ, „Gheorghe Asachi” Technical University of Iaşi, Romania Prof. Mircea BEJAN, Technical University of Cluj Napoca, Romania Acad. Ion BOSTAN, Moldavian Academy, Moldavia Eng. Stelian BULIGA, Head of Network Management E-ON Moldova, Romania Prof. Helmut BURKHARDT, CIWES, Canada Eng. Mihaela CAZACU, Head of Energy Management Department, E-ON Moldova, Romania Prof. Gheorghe CÂRTINĂ, „Gheorghe Asachi” Technical University of Iaşi, Romania Prof. Costin CEPISCA, „Politehnica” University of Bucharest, Romania Prof. -

Www . Polonia Chess.Pl

Amplico_eng 12/11/07 8:39 Page 1 26th MEMORIAL of STANIS¸AW GAWLIKOWSKI UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE CITY OF WARSAW HANNA GRONKIEWICZ-WALTZ AND THE MARSHAL OF THE MAZOWIECKIE VOIVODESHIP ADAM STRUZIK chess.pl polonia VII AMPLICO AIG LIFE INTERNATIONAL CHESS TOURNEMENT EUROPEAN RAPID CHESS CHAMPIONSHIP www. INTERNATIONAL WARSAW BLITZ CHESS CHAMPIONSHIP WARSAW • 14th–16th December 2007 Amplico_eng 12/11/07 8:39 Page 2 7 th AMPLICO AIG LIFE INTERNATIONAL CHESS TOURNAMENT WARSAW EUROPEAN RAPID CHESS CHAMPIONSHIP 15th-16th DEC 2007 Chess Club Polonia Warsaw, MKS Polonia Warsaw and the Warsaw Foundation for Chess Development are one of the most significant organizers of chess life in Poland and in Europe. The most important achievements of “Polonia Chess”: • Successes of the grandmasters representing Polonia: • 5 times finishing second (1997, 1999, 2001, 2003 and 2005) and once third (2002) in the European Chess Club Cup; • 8 times in a row (1999-2006) team championship of Poland; • our players have won 24 medals in Polish Individual Championships, including 7 gold, 11 silver and 4 bronze medals; • GM Bartlomiej Macieja became European Champion in 2002 (the greatest individual success in the history of Polish chess after the Second World War); • WGM Beata Kadziolka won the bronze medal at the World Championship 2005; • the players of Polonia have had qualified for the World Championships and World Cups: Micha∏ Krasenkow and Bart∏omiej Macieja (six times), Monika Soçko (three times), Robert Kempiƒski and Mateusz Bartel (twice), -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E.