The Evects of Time Pressure on Chess Skill: an Investigation Into Fast and Slow Processes Underlying Expert Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

No. 123 - (Vol.VIH)

No. 123 - (Vol.VIH) January 1997 Editorial Board editors John Roycrqfttf New Way Road, London, England NW9 6PL Edvande Gevel Binnen de Veste 36, 3811 PH Amersfoort, The Netherlands Spotlight-column: J. Heck, Neuer Weg 110, D-47803 Krefeld, Germany Opinions-column: A. Pallier, La Mouziniere, 85190 La Genetouze, France Treasurer: J. de Boer, Zevenenderdrffi 40, 1251 RC Laren, The Netherlands EDITORIAL achievement, recorded only in a scientific journal, "The chess study is close to the chess game was not widely noticed. It was left to the dis- because both study and game obey the same coveries by Ken Thompson of Bell Laboratories rules." This has long been an argument used to in New Jersey, beginning in 1983, to put the boot persuade players to look at studies. Most players m. prefer studies to problems anyway, and readily Aside from a few upsets to endgame theory, the give the affinity with the game as the reason for set of 'total information' 5-raan endgame their preference. Your editor has fought a long databases that Thompson generated over the next battle to maintain the literal truth of that ar- decade demonstrated that several other endings gument. It was one of several motivations in might require well over 50 moves to win. These writing the final chapter of Test Tube Chess discoveries arrived an the scene too fast for FIDE (1972), in which the Laws are separated into to cope with by listing exceptions - which was the BMR (Board+Men+Rules) elements, and G first expedient. Then in 1991 Lewis Stiller and (Game) elements, with studies firmly identified Noam Elkies using a Connection Machine with the BMR realm and not in the G realm. -

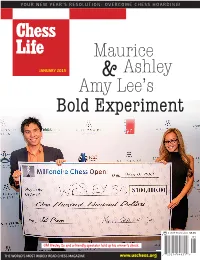

Bold Experiment YOUR NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTION: OVERCOME CHESS HOARDING!

Bold Experiment YOUR NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTION: OVERCOME CHESS HOARDING! Maurice JANUARY 2015 & Ashley Amy Lee’s Bold Experiment FineLine Technologies JN Index 80% 1.5 BWR PU JANUARY A USCF Publication $5.95 01 GM Wesley So and a friendly spectator hold up his winner’s check. 7 25274 64631 9 IFC_Layout 1 12/10/2014 11:28 AM Page 1 SLCC_Layout 1 12/10/2014 11:50 AM Page 1 The Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis is preparing for another fantastic year! 2015 U.S. Championship 2015 U.S. Women’s Championship 2015 U.S. Junior Closed $10K Saint Louis Open GM/IM Title Norm Invitational 2015 Sinquefi eld Cup $10K Thanksgiving Open www.saintlouischessclub.org 4657 Maryland Avenue, Saint Louis, MO 63108 | (314) 361–CHESS (2437) | [email protected] NON-DISCRIMINATION POLICY: The CCSCSL admits students of any race, color, nationality, or ethnic origin. THE UNEXPECTED COLLISION OF CHESS AND HIP HOP CULTURE 2&72%(5r$35,/2015 4652 Maryland Avenue, Saint Louis, MO 63108 (314) 367-WCHF (9243) | worldchesshof.org Photo © Patrick Lanham Financial assistance for this project With support from the has been provided by the Missouri Regional Arts Commission Arts Council, a state agency. CL_01-2014_masthead_JP_r1_chess life 12/10/2014 10:30 AM Page 2 Chess Life EDITORIAL STAFF Chess Life Editor and Daniel Lucas [email protected] Director of Publications Chess Life Online Editor Jennifer Shahade [email protected] Chess Life for Kids Editor Glenn Petersen [email protected] Senior Art Director Frankie Butler [email protected] Editorial Assistant/Copy Editor Alan Kantor [email protected] Editorial Assistant Jo Anne Fatherly [email protected] Editorial Assistant Jennifer Pearson [email protected] Technical Editor Ron Burnett TLA/Advertising Joan DuBois [email protected] USCF STAFF Executive Director Jean Hoffman ext. -

Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames

Games of No Chance MSRI Publications Volume 29, 1996 Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames LEWIS STILLER Abstract. This article has three chief aims: (1) To show the wide utility of multilinear algebraic formalism for high-performance computing. (2) To describe an application of this formalism in the analysis of chess endgames, and results obtained thereby that would have been impossible to compute using earlier techniques, including a win requiring a record 243 moves. (3) To contribute to the study of the history of chess endgames, by focusing on the work of Friedrich Amelung (in particular his apparently lost analysis of certain six-piece endgames) and that of Theodor Molien, one of the founders of modern group representation theory and the first person to have systematically numerically analyzed a pawnless endgame. 1. Introduction Parallel and vector architectures can achieve high peak bandwidth, but it can be difficult for the programmer to design algorithms that exploit this bandwidth efficiently. Application performance can depend heavily on unique architecture features that complicate the design of portable code [Szymanski et al. 1994; Stone 1993]. The work reported here is part of a project to explore the extent to which the techniques of multilinear algebra can be used to simplify the design of high- performance parallel and vector algorithms [Johnson et al. 1991]. The approach is this: Define a set of fixed, structured matrices that encode architectural primitives • of the machine, in the sense that left-multiplication of a vector by this matrix is efficient on the target architecture. Formulate the application problem as a matrix multiplication. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

Extended Null-Move Reductions

Extended Null-Move Reductions Omid David-Tabibi1 and Nathan S. Netanyahu1,2 1 Department of Computer Science, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan 52900, Israel [email protected], [email protected] 2 Center for Automation Research, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA [email protected] Abstract. In this paper we review the conventional versions of null- move pruning, and present our enhancements which allow for a deeper search with greater accuracy. While the conventional versions of null- move pruning use reduction values of R ≤ 3, we use an aggressive re- duction value of R = 4 within a verified adaptive configuration which maximizes the benefit from the more aggressive pruning, while limiting its tactical liabilities. Our experimental results using our grandmaster- level chess program, Falcon, show that our null-move reductions (NMR) outperform the conventional methods, with the tactical benefits of the deeper search dominating the deficiencies. Moreover, unlike standard null-move pruning, which fails badly in zugzwang positions, NMR is impervious to zugzwangs. Finally, the implementation of NMR in any program already using null-move pruning requires a modification of only a few lines of code. 1 Introduction Chess programs trying to search the same way humans think by generating “plausible” moves dominated until the mid-1970s. By using extensive chess knowledge at each node, these programs selected a few moves which they consid- ered plausible, and thus pruned large parts of the search tree. However, plausible- move generating programs had serious tactical shortcomings, and as soon as brute-force search programs such as Tech [17] and Chess 4.x [29] managed to reach depths of 5 plies and more, plausible-move generating programs fre- quently lost to brute-force searchers due to their tactical weaknesses. -

John D. Rockefeller V Embraces Family Legacy with $3 Million Giff to US Chess

Included with this issue: 2021 Annual Buying Guide John D. Rockefeller V Embraces Family Legacy with $3 Million Giftto US Chess DECEMBER 2020 | USCHESS.ORG The United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer 888.51.CHESS (512.4377) www.USCFSales.com So you want to improve your chess? NEW! If you want to improve your chess the best place to start is looking how the great champs did it. dŚƌĞĞͲƟŵĞh͘^͘ŚĂŵƉŝŽŶĂŶĚǁĞůůͲ known chess educator Joel Benjamin ŝŶƚƌŽĚƵĐĞƐĂůůtŽƌůĚŚĂŵƉŝŽŶƐĂŶĚ shows what is important about their play and what you can learn from them. ĞŶũĂŵŝŶƉƌĞƐĞŶƚƐƚŚĞŵŽƐƚŝŶƐƚƌƵĐƟǀĞ games of each champion. Magic names ƐƵĐŚĂƐĂƉĂďůĂŶĐĂ͕ůĞŬŚŝŶĞ͕dĂů͕<ĂƌƉŽǀ ĂŶĚ<ĂƐƉĂƌŽǀ͕ƚŚĞLJ͛ƌĞĂůůƚŚĞƌĞ͕ƵƉƚŽ ĐƵƌƌĞŶƚtŽƌůĚŚĂŵƉŝŽŶDĂŐŶƵƐĂƌůƐĞŶ͘ Of course the crystal-clear style of Bobby &ŝƐĐŚĞƌ͕ƚŚĞϭϭƚŚtŽƌůĚŚĂŵƉŝŽŶ͕ŵĂŬĞƐ for a very memorable chapter. ^ƚƵĚLJŝŶŐƚŚŝƐŬǁŝůůƉƌŽǀĞĂŶĞdžƚƌĞŵĞůLJ ƌĞǁĂƌĚŝŶŐĞdžƉĞƌŝĞŶĐĞĨŽƌĂŵďŝƟŽƵƐ LJŽƵŶŐƐƚĞƌƐ͘ůŽƚŽĨƚƌĂŝŶĞƌƐĂŶĚĐŽĂĐŚĞƐ ǁŝůůĮŶĚŝƚǁŽƌƚŚǁŚŝůĞƚŽŝŶĐůƵĚĞƚŚĞŬ in their curriculum. paperback | 256 pages | $22.95 from the publishers of A Magazine Free Ground Shipping On All Books, Software and DVDS at US Chess Sales $25.00 Minimum – Excludes Clearance, Shopworn and Items Otherwise Marked CONTRIBUTORS DECEMBER Dan Lucas (Cover Story) Dan Lucas is the Senior Director of Strategic Communication for US Chess. He served as the Editor for Chess Life from 2006 through 2018, making him one of the longest serving editors in US Chess history. This is his first cover story forChess Life. { EDITORIAL } CHESS LIFE/CLO EDITOR John Hartmann ([email protected]) -

A Higher Creative Species in the Game of Chess

Articles Deus Ex Machina— A Higher Creative Species in the Game of Chess Shay Bushinsky n Computers and human beings play chess differently. The basic paradigm that computer C programs employ is known as “search and eval- omputers and human beings play chess differently. The uate.” Their static evaluation is arguably more basic paradigm that computer programs employ is known as primitive than the perceptual one of humans. “search and evaluate.” Their static evaluation is arguably more Yet the intelligence emerging from them is phe- primitive than the perceptual one of humans. Yet the intelli- nomenal. A human spectator is not able to tell the difference between a brilliant computer gence emerging from them is phenomenal. A human spectator game and one played by Kasparov. Chess cannot tell the difference between a brilliant computer game played by today’s machines looks extraordinary, and one played by Kasparov. Chess played by today’s machines full of imagination and creativity. Such ele- looks extraordinary, full of imagination and creativity. Such ele- ments may be the reason that computers are ments may be the reason that computers are superior to humans superior to humans in the sport of kings, at in the sport of kings, at least for the moment. least for the moment. This article is about how Not surprisingly, the superiority of computers over humans in roles have changed: humans play chess like chess provokes antagonism. The frustrated critics often revert to machines, and machines play chess the way humans used to play. the analogy of a competition between a racing car and a human being, which by now has become a cliché. -

3 Fischer Vs. Bent Larsen

Copyright © 2020 by John Donaldson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. First Edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Donaldson, John (William John), 1958- author. Title: Bobby Fischer and his world / by John Donaldson. Description: First Edition. | Los Angeles : Siles Press, 2020. Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020031501 ISBN 9781890085193 (Trade Paperback) ISBN 9781890085544 (eBook) Subjects: LCSH: Fischer, Bobby, 1943-2008. | Chess players--United States--Biography. | Chess players--Anecdotes. | Chess--Collections of games. | Chess--Middle games. | Chess--Anecdotes. | Chess--History. Classification: LCC GV1439.F5 D66 2020 | DDC 794.1092 [B]--dc23 Cover Design and Artwork by Wade Lageose a division of Silman-James Press, Inc. www.silmanjamespress.com [email protected] CONTENTS Acknowledgments xv Introduction xvii A Note to the Reader xx Part One – Beginner to U.S. Junior Champion 1 1. Growing Up in Brooklyn 3 2. First Tournaments 10 U.S. Amateur Championship (1955) 10 U.S. Junior Open (1955) 13 3. Ron Gross, The Man Who Knew Bobby Fischer 33 4. Correspondence Player 43 5. Cache of Gems (The Targ Donation) 47 6. “The year 1956 turned out to be a big one for me in chess.” 51 7. “Let’s schusse!” 57 8. “Bobby Fischer rang my doorbell.” 71 9. 1956 Tournaments 81 U.S. Amateur Championship (1956) 81 U.S. Junior (1956) 87 U.S Open (1956) 88 Third Lessing J. -

Glossary of Chess

Glossary of chess See also: Glossary of chess problems, Index of chess • X articles and Outline of chess • This page explains commonly used terms in chess in al- • Z phabetical order. Some of these have their own pages, • References like fork and pin. For a list of unorthodox chess pieces, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems; for a list of chess-related games, see Chess variants. 1 A Contents : absolute pin A pin against the king is called absolute since the pinned piece cannot legally move (as mov- ing it would expose the king to check). Cf. relative • A pin. • B active 1. Describes a piece that controls a number of • C squares, or a piece that has a number of squares available for its next move. • D 2. An “active defense” is a defense employing threat(s) • E or counterattack(s). Antonym: passive. • F • G • H • I • J • K • L • M • N • O • P Envelope used for the adjournment of a match game Efim Geller • Q vs. Bent Larsen, Copenhagen 1966 • R adjournment Suspension of a chess game with the in- • S tention to finish it later. It was once very common in high-level competition, often occurring soon af- • T ter the first time control, but the practice has been • U abandoned due to the advent of computer analysis. See sealed move. • V adjudication Decision by a strong chess player (the ad- • W judicator) on the outcome of an unfinished game. 1 2 2 B This practice is now uncommon in over-the-board are often pawn moves; since pawns cannot move events, but does happen in online chess when one backwards to return to squares they have left, their player refuses to continue after an adjournment. -

Garry Kasparov Became the GARRY Under-18 Chess Champion of the USSR at the Age of 12 and the World Under-20 Champion at 17

Born in Baku, Azerbaijan, in the Soviet Union in 1963, Garry Kasparov became the GARRY under-18 chess champion of the USSR at the age of 12 and the world under-20 champion at 17. He came to international fame at the age of 22 as the youngest world chess champion in history in 1985. He defended his title five times, including a legendary series of matches against arch-rival Anatoly Karpov. Kasparov broke KASPAROV Bobby Fischer’s rating record in 1990 and his own peak rating record remained unbroken until 2013. His famous matches against the IBM super-computer Deep Blue in 1996-97 were key to bringing artificial intelligence, and chess, into the mainstream. World Chess Champion, Kasparov’s outspoken nature did not endear him to the Soviet authorities, giving him an early taste of opposition politics. He became one of the first prominent Author, Master of Strategy Soviets to call for democratic and market reforms and was an early supporter of Boris Yeltsin’s push to break up the Soviet Union. In 1990, he and his family escaped ethnic violence in his native Baku as the USSR collapsed. His refusal that year to play the World Championship under the Soviet flag caused an international sensation. In 2005, Kasparov, in his 20th year as the world’s top-ranked player, abruptly retired from competitive chess to join the vanguard of the Russian pro- democracy movement. He founded the United Civil Front and organized the Marches of Dissent to protest the repressive policies of Vladimir Putin. In 2012, Kasparov was named chairman of the New York-based Human Rights Foundation, succeeding Vaclav Havel.Facing imminent arrest during Putin’s crackdown, Kasparov moved from Moscow to New York City in 2013. -

FIDE LAWS of CHESS

E.I.01 FIDE LAWS of CHESS Contents: PREFACE page 2 BASIC RULES OF PLAY Article 1: The nature and objectives of the game of chess page 2 Article 2: The initial position of the pieces on the chessboard page 3 Article 3: The moves of the pieces page 4 Article 4: The act of moving the pieces page 7 Article 5: The completion of the game page 8 COMPETITION RULES Article 6: The chess clock page 9 Article 7: Irregularities page 11 Article 8: The recording of the moves page 11 Article 9: The drawn game page 12 Article 10: Quickplay finish page 13 Article 11: Points page 14 Article 12: The conduct of the players page 14 Article 13: The role of the arbiter (see Preface) page 15 Article 14: FIDE page 16 Appendices: A. Rapidplay page 17 B. Blitz page 17 C. Algebraic notation page 18 D. Quickplay finishes where no arbiter is present in the venue page 20 E. Rules for play with Blind and Visually Handicapped page 20 F. Chess960 rules page 22 Guidelines in case a game needs to be adjourned page 24 1 FIDE Laws of Chess cover over-the-board play. The English text is the authentic version of the Laws of Chess, which was adopted at the 79th FIDE Congress at Dresden (Germany), November 2008, coming into force on 1 July 2009. In these Laws the words ‘he’, ‘him’ and ‘his’ include ‘she’ and ‘her’. PREFACE The Laws of Chess cannot cover all possible situations that may arise during a game, nor can they regulate all administrative questions.