The Lutheran Church and Latvian National Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Systems in Transition

61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 1 03/03/2020 09:55 Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Vol. Health Systems in Transition Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Health Systems in Transition: in Transition: Health Systems C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Latvia Latvia Health system review Daiga Behmane Alina Dudele Anita Villerusa Janis Misins The Observatory is a partnership, hosted by WHO/Europe, which includes other international organizations (the European Commission, the World Bank); national and regional governments (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Kristine Klavina Ireland, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the Veneto Region of Italy); other health system organizations (the French National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM), the Dzintars Mozgis Health Foundation); and academia (the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the Giada Scarpetti London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)). The Observatory has a secretariat in Brussels and it has hubs in London at LSE and LSHTM) and at the Berlin University of Technology. HiTs are in-depth profiles of health systems and policies, produced using a standardized approach that allows comparison across countries. They provide facts, figures and analysis and highlight reform initiatives in progress. Print ISSN 1817-6119 Web ISSN 1817-6127 61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 2 03/03/2020 09:55 Giada Scarpetti (Editor), and Ewout van Ginneken (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European -

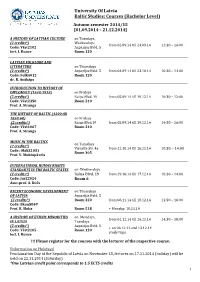

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

Circular Economy and Bioeconomy Interaction Development As Future for Rural Regions. Case Study of Aizkraukle Region in Latvia

Environmental and Climate Technologies 2019, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 129–146 doi: 10.2478/rtuect-2019-0084 https://content.sciendo.com Circular Economy and Bioeconomy Interaction Development as Future for Rural Regions. Case Study of Aizkraukle Region in Latvia Indra MUIZNIECE1*, Lauma ZIHARE2, Jelena PUBULE3, Dagnija BLUMBERGA4 1–4Institute of Energy Systems and Environment, Riga Technical University, Azenes iela 12/1, Riga, LV-1048, Latvia Abstract – In order to enforce the concepts of bioeconomy and the circular economy, the use of a bottom-up approach at the national level has been proposed: to start at the level of a small region, encourage its development, considering its specific capacities and resources, rather than applying generalized assumptions at a national or international level. Therefore, this study has been carried out with an aim to develop a methodology for the assessment of small rural areas in the context of the circular economy and bioeconomy, in order to advance the development of these regions in an effective way, using the existing bioresources comprehensively. The methodology is based on the identification of existing and potential bioeconomy flows (land and its use, bioresources, human resources, employment and business), the identification of the strengths of their interaction and compare these with the situation at the regional and national levels in order to identify the specific region's current situation in the bioeconomy and identify more forward-looking directions for development. Several methods are integrated and interlinked in the methodology – indicator analysis, correlation and regression analysis, and heat map tables. The methodology is approbated on one case study – Aizkraukle region – a small rural region in Latvia. -

From Tribe to Nation a Brief History of Latvia

From Tribe to Nation A Brief History of Latvia 1 Cover photo: Popular People of Latvia are very proud of their history. It demonstration on is a history of the birth and development of the Dome Square, 1989 idea of an independent nation, and a consequent struggle to attain it, maintain it, and renew it. Above: A Zeppelin above Rīga in 1930 Albeit important, Latvian history is not entirely unique. The changes which swept through the ter- Below: Participants ritory of Latvia over the last two dozen centuries of the XXV Nationwide were tied to the ever changing map of Europe, Song and Dance and the shifting balance of power. From the Viking Celebration in 2013 conquests and German Crusades, to the recent World Wars, the territory of Latvia, strategically lo- cated on the Baltic Sea between the Scandinavian region and Russia, was very much part of these events, and shared their impact especially closely with its Baltic neighbours. What is unique and also attests to the importance of history in Latvia today, is how the growth and development of a nation, initially as a mere idea, permeated all these events through the centuries up to Latvian independence in 1918. In this brief history of Latvia you can read how Latvia grew from tribe to nation, how its history intertwined with changes throughout Europe, and how through them, or perhaps despite them, Lat- via came to be a country with such a proud and distinct national identity 2 1 3 Incredible Historical Landmarks Left: People of The Baltic Way – this was one of the most crea- Latvia united in the tive non-violent protest activities in history. -

The Courlander Experience in Tobago

THE COURLANDER EXPERIENCE IN TOBAGO THE REPUBLIC OF LATVIA: A maritime nation on the Baltic sea with excellent ports, 64.589km2 in area and a population of nearly 2.000.000 inhabitants. There are apx. 1.500.000 Latvians living in Latvia and the rest of the world. 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Republic of Latvia. COURLANDERS: Latvians from the province of Courland (Kurzeme). In the days of the Duchy of Courland and Semgallia, a “Courlander” could also be an inhabitant of the province of Semgallia. “Courlander” is a literal translation of the Latvian kurzemnieks. The academic word for anything pertaining to Courland is Couronian. THE DUCHY OF COURLAND AND SEMGALLIA: A de facto independent nation formed in 1561 and existing until 1795, comprised of 2 modern day provinces of Latvia, and ruled by the German-Baltic dukes of Courland, although officially a part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The flags of Courland consisted of a red and white 2 band flag and the red and black “crab” flag which originated in Tobago, as there are no crabs of this type in Latvia. As such, it can be considered the first flag of Tobago. CHRONOLOGY 1639 Sent by Duke Jacob, probably involuntarily, 212 Courlanders arrive in Tobago. Unprepared for tropical conditions, they eventually perish. 1642 (possibly 1640) Duke Jacob engages a Brazilian, capt. Cornelis Caroon (later, Caron) to lead a colony comprised basically of Dutch Zealanders, that probably establishes itself in the flat, southwestern portion of the island. Under attack by the Caribs, 70 remaining members of the original 310 colonists are evacuated to Pomeron, Guyana, by the Arawaks. -

Evidence of the Reformation and Confessionalization Period in Livonian Art

Ojārs Spārītis EVIDENCE OF THE REFORMATION AND CONFESSIONALIZATION PerIOD IN LIVONIAN ArT INTRODUCTION The singular transitional period that led from the slowly evolving me- dieval vision of the world to a new perception of life with its dynamic expression in works of history and art history texts has been given labels that reflect its chronological evolution, as well as the epithets referring to its philosophical and aesthetic content. To illustrate the variety of the social and spiritual aspects of European spiritual life in the second half of the 15th and the 16th century, literature in the humanitarian spheres exploited concepts from the Renaissance, the Reformation and Counter- Reformation. Concepts of both humanism and hedonism were used to characterize the domestic cultural content and form. However, they fail to reveal the development of the new historical period and contradic- tion-rich diversity of the material and spiritual life in the 15th and 16th centuries, when the growing dominance of economic expansion and the endeavours to acquire new knowledge along with the awareness of the tangible benefits and spiritual advantages of a university education was so characteristic of European culture. The history of spiritual evolution, with the variations related to the Reformation and confessionalization, is characterised by local regional contexts and forms of expression, but it also has a mandatory syn- chronicity with the processes of European political and intellectual life. Looking forward to the 500th anniversary of the Reformation initi- DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12697/BJAH.2015.9.03 24 Ojārs Spārītis Reformation and Confessionalization Period in Livonian Art 25 ated by Martin Luther, it is worth examining the Renaissance-marked – the Teutonic Order and the bishops – used both political and spiritual fine arts testimonies from the central part of the Livonian confedera- methods in their battle for economic power in Riga. -

The Saeima (Parliament) Election

/pub/public/30067.html Legislation / The Saeima Election Law Unofficial translation Modified by amendments adopted till 14 July 2014 As in force on 19 July 2014 The Saeima has adopted and the President of State has proclaimed the following law: The Saeima Election Law Chapter I GENERAL PROVISIONS 1. Citizens of Latvia who have reached the age of 18 by election day have the right to vote. (As amended by the 6 February 2014 Law) 2.(Deleted by the 6 February 2014 Law). 3. A person has the right to vote in any constituency. 4. Any citizen of Latvia who has reached the age of 21 before election day may be elected to the Saeima unless one or more of the restrictions specified in Article 5 of this Law apply. 5. Persons are not to be included in the lists of candidates and are not eligible to be elected to the Saeima if they: 1) have been placed under statutory trusteeship by the court; 2) are serving a court sentence in a penitentiary; 3) have been convicted of an intentionally committed criminal offence except in cases when persons have been rehabilitated or their conviction has been expunged or vacated; 4) have committed a criminal offence set forth in the Criminal Law in a state of mental incapacity or a state of diminished mental capacity or who, after committing a criminal offence, have developed a mental disorder and thus are incapable of taking or controlling a conscious action and as a result have been subjected to compulsory medical measures, or whose cases have been dismissed without applying such compulsory medical measures; 5) belong -

Gradients of Latvian Magnetic Anomalies

Scientific Journal of Riga Technical University Sustainable Spatial Development 2011 __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Volume 2 Gradients of Latvian Magnetic Anomalies Vladimir Vertennikov, Riga Technical University Abstract. This article discusses one of the most important and vertical gradients. It is possible to determine those geophysical factors, which produces an impact on the gradients by calculations or measurements using special demographic processes and reflects the nature of variability in instruments – magnetic gradiometers. Instrumented gradient the anomalous magnetic field intensity in space. The article characterises the horizontal magnetic gradients, which vary measurements are predominantly utilised in local areas during within the wide range: from 10 to 2400 nT/km. It distinguishes prospecting and exploration for minerals. In regional magnetic scale and magnetic gradient areas. The article gives an investigations, to which concrete operations associated with ecodemographic evaluation of the territory of Latvia by the investigating the impact of geophysical factors on gradience of the anomalous magnetic field. demographic processes belong, horizontal gradients are the main factor; they are determined by calculations. Keywords: horizontal magnetic gradient, magnetic scale, magnetic gradient area, ecodemographic evaluation of territory by magnetic gradience. CHARACTERISATION OF HORIZONTAL MAGNETIC GRADIENTS The magnetic field is represented in the Latvian territory by a complex set of anomalies with different signs, intensity, size The gradient is an important parameter of anomalous and morphology. The transitions from one anomaly to another magnetic field. The discussion deals with the spatial intensity are expressed through changes in the field intensity and are variations. The thing is that the intensity of the anomalous either gradual, occurring step-by-step, or abrupt. -

Celebrating 100 Years of the Baroness Ada Von Manteuffel Bequest1

Celebrating 100 Years of the Baroness Ada von Manteuffel Bequest1 Translation of an address delivered by Baron Ernst-Dietrich von Mirbach to celebrate the 100th Anniversary of the United Kurland2 Bequests (VKS) on 21 June 2014 The German government official based in Munich who assesses Bavaria’s not-for-profit sector for tax compliance was more than surprised when she came to realise recently that the United Kurland Bequests (Vereinigte Kurländische Stiftungen or VKS3) were going to be 100 years old in 2014. That’s what the VKS’s managing director put in his report in vol. 20 of its Kurland magazine in 2013. While the VKS might not be Germany’s oldest endowment, few can match its success in bringing so much of its seed capital unscathed through the last 100 years of revolution, inflation and tumult. That same tax official would be still more surprised to discover just how many of us have turned up today here in Dresden at the Kurländer Palais to celebrate the Bequest’s 100 th birthday. And it’s not even an endowment that has its roots in Germany! Rather, it springs from a generous gift made to the Kurland Knighthood (or Noble Corporation - Kurländische Ritterschaft) in Nice back in 1914. Getting the legacy paid out in 1921 in the face of nigh insuperable odds was the biggest achievement. That’s been the remarkable success of some particularly determined Kurland Knighthood members. No need to wonder, therefore, about also being able to celebrate this 100-year anniversary in this remarkable venue, full of associations for so many of us, and not least because of its historic name. -

Between National and Academic Agendas Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940

BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Other titles in the same series Södertörn Studies in History Git Claesson Pipping & Tom Olsson, Dyrkan och spektakel: Selma Lagerlöfs framträdanden i offentligheten i Sverige 1909 och Finland 1912, 2010. Heiko Droste (ed.), Connecting the Baltic Area: The Swedish Postal System in the Seventeenth Century, 2011. Susanna Sjödin Lindenskoug, Manlighetens bortre gräns: tidelagsrättegångar i Livland åren 1685–1709, 2011. Anna Rosengren, Åldrandet och språket: En språkhistorisk analys av hög ålder och åldrande i Sverige cirka 1875–1975, 2011. Steffen Werther, SS-Vision und Grenzland-Realität: Vom Umgang dänischer und „volksdeutscher” Nationalsozialisten in Sønderjylland mit der „großgermanischen“ Ideologie der SS, 2012. Södertörn Academic Studies Leif Dahlberg och Hans Ruin (red.), Fenomenologi, teknik och medialitet, 2012. Samuel Edquist, I Ruriks fotspår: Om forntida svenska österledsfärder i modern historieskrivning, 2012. Jonna Bornemark (ed.), Phenomenology of Eros, 2012. Jonna Bornemark och Hans Ruin (eds), Ambiguity of the Sacred, 2012. Håkan Nilsson (ed.), Placing Art in the Public Realm, 2012. Lars Kleberg and Aleksei Semenenko (eds), Aksenov and the Environs/Aksenov i okrestnosti, 2012. BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Södertörns högskola Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image, taken from Latvijas Universitāte Illūstrācijās, p. 10. Gulbis, Riga, 1929. Cover: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson and Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Studies in History 13 ISSN 1653-2147 Södertörn Academic Studies 51 ISSN 1650-6162 ISBN 978-91-86069-52-0 Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................................... -

Annual Report on the Year 2011 by Ombudsman of the Republic of Latvia

Annual Report on the year 2011 by Ombudsman of the Republic of Latvia Riga, 2012 2 Preamble by the Ombudsman ........................................................................... 7 Protection of the Rights of children .................................................................. 10 What are the rights of children? ............................................................................................... 10 Priorities in the field of the rights of children ........................................................................... 10 I. Children in state social care facilities (nursing homes)...................................... 11 1. The right of child to grow up in family................................................................................. 11 2. The right of child with special needs to grow up in family.................................................... 13 3. Ensuring of the right of siblings to be not separated ............................................................. 14 4. Number of children accomodated at PSCCs and their right to qualitative care...................... 15 5. Alternative forms of care...................................................................................................... 16 6. Social work with a family .................................................................................................... 18 7. Immediate steps to be taken to ensure the right of children to grow up in family or to ensure family-based care.................................................................................................................... -

(UN/LOCODE) for Latvia

United Nations Code for Trade and Transport Locations (UN/LOCODE) for Latvia N.B. To check the official, current database of UN/LOCODEs see: https://www.unece.org/cefact/locode/service/location.html UN/LOCODE Location Name State Functionality Status Coordinatesi LV 6LV Alsunga 006 Road terminal; Recognised location 5659N 02134E LV AGL Aglona 001 Road terminal; Recognised location 5608N 02701E LV AIN Ainazi 054 Port; Code adopted by IATA or ECLAC 5752N 02422E LV AIZ Aizkraukle 002 Port; Rail terminal; Road terminal; Recognised location 5636N 02513E LV AKI Akniste JKB Road terminal; Multimodal function, ICD etc.; Recognised location 5610N 02545E LV ALJ Aloja 005 Road terminal; Recognised location 5746N 02452E LV AMT Amata 008 Road terminal; Recognised location 5712N 02509E LV APE Aizpute 003 Road terminal; Recognised location 5643N 02136E LV APP Ape 007 Road terminal; Recognised location 5732N 02640E LV ARX Avoti RIX Road terminal; Recognised location 5658N 02350E LV ASE Aluksne 002 Rail terminal; Road terminal; Recognised location 5725N 02703E LV AUC Auce 010 Rail terminal; Road terminal; Recognised location 5628N 02254E LV B8R Balozi 052 Road terminal; Recognised location 5652N 02407E LV B9G Baldone 013 Port; Road terminal; Recognised location 5644N 02423E LV BAB Babite 079 Road terminal; Recognised location 5657N 02357E LV BAL Balvi 015 Rail terminal; Road terminal; Recognised location 5708N 02715W LV BAU Bauska 016 Rail terminal; Road terminal; Recognised location 5624N 02411E LV BLN Baltinava 014 Road terminal; Recognised location