Chapter 1: Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

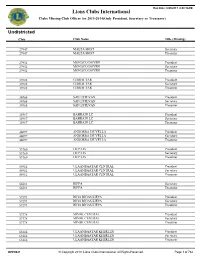

All Clubs Missing Officers Current Year.Pdf

Run Date: 8/29/2013 8:40:18AM Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing Club Officer for 2013-2014(Only President, Secretary or Treasurer) Undistricted Club Club Name Title (Missing) 27947 MALTA HOST Secretary 27947 MALTA HOST Treasurer 27952 MONACO DOYEN President 27952 MONACO DOYEN Secretary 27952 MONACO DOYEN Treasurer 33988 GIBRALTAR President 33988 GIBRALTAR Secretary 33988 GIBRALTAR Treasurer 34968 SAN ESTEVAN President 34968 SAN ESTEVAN Secretary 34968 SAN ESTEVAN Treasurer 35917 BAHRAIN LC President 35917 BAHRAIN LC Secretary 35917 BAHRAIN LC Treasurer 44697 ANDORRA DE VELLA President 44697 ANDORRA DE VELLA Secretary 44697 ANDORRA DE VELLA Treasurer 53760 LIEPAJA President 53760 LIEPAJA Secretary 53760 LIEPAJA Treasurer 54912 ULAANBAATAR CENTRAL President 54912 ULAANBAATAR CENTRAL Secretary 54912 ULAANBAATAR CENTRAL Treasurer 56581 RIFFA Secretary 56581 RIFFA Treasurer 57293 RIGA RIGAS LIEPA President 57293 RIGA RIGAS LIEPA Secretary 57293 RIGA RIGAS LIEPA Treasurer 57378 MINSK CENTRAL President 57378 MINSK CENTRAL Secretary 57378 MINSK CENTRAL Treasurer 63886 ULAANBAATAR KHERLEN President 63886 ULAANBAATAR KHERLEN Secretary 63886 ULAANBAATAR KHERLEN Treasurer OFF0021 © Copyright 2013, Lions Clubs International, All Rights Reserved. Page 1 of 784 Run Date: 8/29/2013 8:40:18AM Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing Club Officer for 2013-2014(Only President, Secretary or Treasurer) Undistricted Club Club Name Title (Missing) 63891 PHNOM PENH CENTRAL President 63891 PHNOM PENH CENTRAL Secretary 63891 PHNOM PENH CENTRAL Treasurer 63902 -

I Love Korea!

I Love Korea! TheThe story story of of why why 33 foreignforeign tourists tourists fellfell in in love love with Korea. Korea. Co-plannedCo-planned by bythe the Visit Visit Korea Korea Committee Committee & & the the Korea Korea JoongAng JoongAng Daily Daily I Love Korea! The story of why 33 foreign tourists fell in love with Korea. Co-planned by the Visit Korea Committee & the Korea JoongAng Daily I Love Korea! This book was co-published by the Visit Korea Committee and the Korea JoongAng Daily newspaper. “The Korea Foreigners Fell in Love With” was a column published from April, 2010 until October, 2012 in the week& section of the Korea JoongAng Daily. Foreigners who visited and saw Korea’s beautiful nature, culture, foods and styles have sent in their experiences with pictures attached. I Love Korea is an honest and heart-warming story of the Korea these people fell in love with. c o n t e n t s 012 Korea 070 Heritage of Korea _ Tradition & History 072 General Yi Sun-sin 016 Nature of Korea _ Mountains, Oceans & Roads General! I get very emotional seeing you standing in the middle of Seoul with a big sword 018 Bicycle Riding in Seoul 076 Panmunjeom & the DMZ The 8 Streams of Seoul, and Chuseok Ah, so heart breaking! 024 Hiking the Baekdudaegan Mountain Range Only a few steps separate the south to the north Yikes! Bang! What?! Hahaha…an unforgettable night 080 Bukchon Hanok Village, Seoul at the Jirisan National Park’s Shelters Jeongdok Public Library, Samcheong Park and the Asian Art Museum, 030 Busan Seoul Bicycle Tour a cluster of -

2021 Finalist Directory

2021 Finalist Directory April 29, 2021 ANIMAL SCIENCES ANIM001 Shrimply Clean: Effects of Mussels and Prawn on Water Quality https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51706 Trinity Skaggs, 11th; Wildwood High School, Wildwood, FL ANIM003 Investigation on High Twinning Rates in Cattle Using Sanger Sequencing https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51833 Lilly Figueroa, 10th; Mancos High School, Mancos, CO ANIM004 Utilization of Mechanically Simulated Kangaroo Care as a Novel Homeostatic Method to Treat Mice Carrying a Remutation of the Ppp1r13l Gene as a Model for Humans with Cardiomyopathy https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51789 Nathan Foo, 12th; West Shore Junior/Senior High School, Melbourne, FL ANIM005T Behavior Study and Development of Artificial Nest for Nurturing Assassin Bugs (Sycanus indagator Stal.) Beneficial in Biological Pest Control https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51803 Nonthaporn Srikha, 10th; Natthida Benjapiyaporn, 11th; Pattarapoom Tubtim, 12th; The Demonstration School of Khon Kaen University (Modindaeng), Muang Khonkaen, Khonkaen, Thailand ANIM006 The Survival of the Fairy: An In-Depth Survey into the Behavior and Life Cycle of the Sand Fairy Cicada, Year 3 https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51630 Antonio Rajaratnam, 12th; Redeemer Baptist School, North Parramatta, NSW, Australia ANIM007 Novel Geotaxic Data Show Botanical Therapeutics Slow Parkinson’s Disease in A53T and ParkinKO Models https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51887 Kristi Biswas, 10th; Paxon School for Advanced Studies, Jacksonville, -

ACTIVITY CARDS 24-36 Months

ACTIVITY CARDS 24-36 months These cards are designed for teachers of two-year-olds Georgia Early Learning and Development Standards gelds.decal.ga.gov Georgia Early Learning and Development Standards gelds.decal.ga.gov /64 33 57/64 14 9 5 32 /64 1 33 5/64 23 /4 14 /64 32 <<---Grain--->> decal.ga.gov 2 57/64 dards Teacher an Toolbox ent St pm / rly Learning and Develo 64 Ea ia 17 eorg 8 Activities based on the GeorgiaG Early Learning and Development Standards 4 gelds.decal.ga.gov 8-17/64") 1/4 Bleed 23 INDEX YOUR OWN ACTIVITIES COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT Cover:SOCIAL STUDIES | SS8-57/64 x 4-17/64 x 2" BRIGHT IDEAS COGNITIVEWrap: 14-33/64 x 9-57/64" DEVELOPMENTMATH | MA Teacher Toolbox Activities17 based onCOGNITIVE the Georgia Early Learning and Development Standards Liner: None / DEVELOPMENTC0GNITIVE 4 64 PROCESSES | CP COMMUNICATION,LANGUAGE Blank: .080 w1s (12-57/64 x 57 AND LITERACY | CLL / Georgi a Early Learning and Developm COGNITIVE ent Standards 64 gelds.decal.ga.gov 9 DEVELOPMENT CREATIVE 57 decal.ga.gov Post production die cut DEVELOPMENT | CR APPROACHESTO PLAY /64 8AND LEARNING | APL COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT SCIENCE | SC SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT | SED SCHOOL PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT AND MOTOR SKILLS | PDM Bleed 2 and Development Standards Activities based on the Georgia Early Learning side Post production die cut <<---Grain--->> ndards t Sta en opm vel rning and De ea rly L eorgia Ea 22.247 G gelds.decal.ga.gov decal.ga.gov D Cover: 8-57/64 x 4-17/64 x 2" 4 Base: 8-5/8Wrap: x 4 x 6-1/2" 14-33/64 x 9-57/64" 5/ 4 Wrap: 23-1/4 x 18-5/8" 18 8 5 Liner: None /8 Liner: None D d 8 ecal. -

Downloading and Pirating of Dvds Throughout the Regions, Again a Strategy Typically Used by Hollywood Majors

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/1153 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. ýý Rethinking Media flow under Globalisation: Rising Korean Wave and Korean TV and Film Policy Since 1980s w by Ju Young Kim A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirementsfor the degreeof Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Policy Studies University of Warwick, Centre for Cultural Policy Studies May 2007 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT LIST OF GRAPHS LIST OF TABLES PART I. INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY CHAPTER 1. The Korean Wave: a New Trend in Media Flow ?.......... 1 1.1 THE KOREAN WAVE AS A COUNTER-FLOW 1 ................................... 1.2 OVERVIEW OF THE KOREAN WAVE IN POP CULTURE 5 .................... 1.2.1 Definition and Development of the Korean Wave'Hanryu................. 11 1.2.2 The Impact of'Hanryu............................................................. 24 1.3 METHODOLOGY OF RESEARCH 39 ................................................ CHAPTER 2. Globalisation Media Flow Theory 47 and ................... 2.1 THEORIES ON THE FLOW OF CULTURAL PRODUCTS 47 .................... 2.1.1 Economy Scale 54 of ............................................................... 2.1.2 Cultural Discount 5 8 ............................................................... 2.2 FORMS OF MEDIA FLOW 63 ......................................................... 2.2.1 One Way Flow: Cultural Imperialism 64 ....................................... 2.2.2 Two Multi-Way Flows 69 or ...................................................... 2.3 ISSUES ON THE WORLD TRADE OF CULTURAL PRODUCTS.......... -

Unofficial Lakota Language Guide Aho! Metakuye Oyasin

Unofficial Lakota Language Guide Aho! Metakuye Oyasin. I have developed this page as an aid to those folks whom are new at learning the Lakota way of life and the ceremonies and language that accompany it. It is my hope that by learning the bits and pieces of the language that I am presenting to you here that the prayers, songs, and teachings that you may become exposed to you will make more sense to you so that you may broaden your knowledge of this beautiful Lakota way of life. To all my relations, Yellowhand Source: http://yellowhand.tripod.com/lakota.html Lakota 101 bloka(blo-kah).... the male of animals blotahonka(blo-tah-hoon-kah.... advisors, leaders, to a large war party. bo-ton-ton(bo-toon-toon).... confusion can(chun).... wood [preffix to anything made of wood] can cega(chun chay-guh).... drum cankuna(chun-koo-na).... little path cannakpaa(chun-nah-k'pah).... mushroom growing on trees : literally "tree-ears" Canoni(chun-oh-nee).... wanderers in the woods: some Dakota families who eventually come onto the plain canozake(chun-oh-zhah-kay).... fork in the tree. canpamiyanwagon(chun-pah-h'mee-yahn) : wagon, literally "rolling wood" canpazachun-pah-zah).... wood pointing to the sky, ancient term for "tree" Cante Tinza(chun-tay t-een-zah).... brave heart, word used for warrior society canunpa(chun-noon-pah).... sacred pipe canunpa o'ke(chun-noon-pah oh-k ay).... pipe dig, pipe stone. canshasha(chun-shaw-shaw).... red willow bark cante(chun-tay).... heart capa(cha-pah).... beaver: literally "swims-stick-in-mouth". -

Songs in the Key of Z

covers complete.qxd 7/15/08 9:02 AM Page 1 MUSIC The first book ever about a mutant strain ofZ Songs in theKey of twisted pop that’s so wrong, it’s right! “Iconoclast/upstart Irwin Chusid has written a meticulously researched and passionate cry shedding long-overdue light upon some of the guiltiest musical innocents of the twentieth century. An indispensable classic that defines the indefinable.” –John Zorn “Chusid takes us through the musical looking glass to the other side of the bizarro universe, where pop spelled back- wards is . pop? A fascinating collection of wilder cards and beyond-avant talents.” –Lenny Kaye Irwin Chusid “This book is filled with memorable characters and their preposterous-but-true stories. As a musicologist, essayist, and humorist, Irwin Chusid gives good value for your enter- tainment dollar.” –Marshall Crenshaw Outsider musicians can be the product of damaged DNA, alien abduction, drug fry, demonic possession, or simply sheer obliviousness. But, believe it or not, they’re worth listening to, often outmatching all contenders for inventiveness and originality. This book profiles dozens of outsider musicians, both prominent and obscure, and presents their strange life stories along with photographs, interviews, cartoons, and discographies. Irwin Chusid is a record producer, radio personality, journalist, and music historian. He hosts the Incorrect Music Hour on WFMU; he has produced dozens of records and concerts; and he has written for The New York Times, Pulse, New York Press, and many other publications. $18.95 (CAN $20.95) ISBN 978-1-55652-372-4 51895 9 781556 523724 SONGS IN THE KEY OF Z Songs in the Key of Z THE CURIOUS UNIVERSE OF O U T S I D E R MUSIC ¥ Irwin Chusid Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chusid, Irwin. -

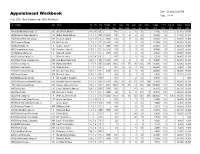

2020 Appointment Workbook

Appointment Workbook Date 2/12/2020 6:00 PM Page 1 of 34 Year: 2020, Show Statistics from: 2019, All Districts # Charge Dist Pastor Yrs Yrs Conf HA Amt CH New Prof Gain Avg Online Tot App % Pd Eq Comp Salary Salary Un Pr Rel 2020 Mbrs Mbrs Faith Loss Wor Wor 2019 2019 2020 2019 2020 798 Paris Mountain Charge (2) W Karen D.M. Adams 15 15 RL 118 -4 30 8,739 100 21,311 20,711 296 Bethany Charge (Hampton) YR Esther Naana Agbosu 7 2 FE 19,200 193 14 6 6 88 40,365 92 51,500 53,045 716 Ramsey Memorial Charge Rd Norma E. Aguilar 13 13 PL 8,000 505 8 5 -2 134 58,107 100 30,000 30,600 592 Fairmount Charge Rd Mi Sook Ahn 7 3 PE 16,000 65 -2 25 22,188 100 38,500 38,500 394 Bath Charge (4) S Lorrie J. Aikens 9 8 FL 3 BR 387 9 2 1 135 26,793 100 45,661 46,791 676 Sleepy Hollow Charge AR Jennifer L. Ailstock 15 1 FL 24,012 137 3 1 1 40 47,568 45 36,000 36,000 571 Madison Charge (2) C Daniel H. Albrant 3 3 FL 4 BR 314 4 -2 78 23,007 100 38,000 39,300 872 Peaksview Charge (2) L Russel K. Alden 4 4 PL 117 -2 27 6,753 71 14,400 15,600 293 Trinity Charge (King George) RR Luis Edward Alderman 20 1 FE 18,000 279 2 2 72 3 34,998 100 52,000 53,200 310 Floris Charge (4) AR Ashley Blair Allen 7 7 FE 26,000 3,480 117 57 96 1,132 245 485,691 100 52,000 52,000 959 New Town Charge YR Marie B. -

Lee, Jeung Yeon (2010) 'My Body Is Korean, but Not My Child's ...': a Foucauldian Approach to Korean Migrant Women's Health-Seeking Behaviours in the UK

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Nottingham ePrints Lee, Jeung Yeon (2010) 'My body is Korean, but not my child's ...': a Foucauldian approach to Korean migrant women's health-seeking behaviours in the UK. PhD thesis, University of Nottingham. Access from the University of Nottingham repository: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/11744/1/Lee-PhD.pdf Copyright and reuse: The Nottingham ePrints service makes this work by researchers of the University of Nottingham available open access under the following conditions. · Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. · To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in Nottingham ePrints has been checked for eligibility before being made available. · Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not- for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. · Quotations or similar reproductions must be sufficiently acknowledged. Please see our full end user licence at: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/end_user_agreement.pdf A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the repository url above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. -

Music-Industry-Vs-Pandora.Pdf

INDEX NO. UNASSIGNED NYSCEF DOC. NO. 1 RECEIVED NYSCEF: 04/17/2014 SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK CAPITOL RECORDS, LLC, a Delaware INDEX NO. limited liability corporation; SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT, a Delaware partnership; UMG RECORDINGS, INC., a Delaware corporation; WARNER MUSIC GROUP CORP., a Delaware corporation, and ABKCO MUSIC & RECORDS, INC., a New York corporation, Plaintiffs, V. SUMMONS PANDORA MEDIA, INC., a Delaware Corporation; and DOES 1 through 10, being fictitious and unknown to Plaintiffs, being participants in all or some of the acts alleged against the Defendants in the Complaint, Defendants. To the above named Defendant(s) You are hereby summoned to answer the complaint in this action and to serve a copy of your answer, or, if the complaint is not served with this summons, to serve a notice of appearance, on the Plaintiffs attorney within 20 days after the service of this summons, exclusive of the day of service (or within 30 days after the service is complete if this summons is not personally delivered to you within the State of New York); and in case of your failure to appear or answer, judgment will be taken against you by default for the relief demanded in the complaint. Plaintiff has designated venue as New York County, pursuant to CPLR § 503. The basis for venue in New York County is made pursuant to CPLR § 503(a) and (c). 6032919.1/11224-00128 DATED: New York, New York MITCHELL SILBERBERG & KNUPP LLP April 17, 2014 By: auren J. Wachtler 12 East 49th Street', 30th Floor New York, New York 10017-1028 Telephone: (212) 509-3900 Facsimile: (212) 509-7239 Russell J. -

Election Held Date Between (Report Defaults) and (Repo

Report Title Election Report for Cases Closed Region(s) Election Closed Date (Report Held Date Between Defaults) Between 10/1/2011 (Report 12:00:00 AM Defaults) and 9/30/2012 and (Report 12:00:00 AM Defaults) Case Type Case Name Labor Org 1 Name State City (Report Defaults) (All Choices) (All Choices) (Report Defaults) (Report Defaults) Election Report for Cases Closed NLRB Elections - Summary Time run: 1/17/2013 9:38:28 AM Total Total Total Percent Employees Valid Valid No. of Won by Eligible to Votes Votes Case Type Elections Union Vote for Against Total 1468 59.0% 99,838 46,058 34,810 Elections RC 1202 65.0% 83,153 38,714 29,159 RD 211 41.0% 12,866 5,708 4,770 RM 13 38.0% 755 373 193 UD 42 6.0% 3,064 1,263 688 NLRB Elections - Details Time run: 1/17/2013 9:38:28 AM Region Case Number Case Name Case Case File Closed Case City State Election Number Valid Votes Labor Org 1 Name Stiplulated Union Union To Certify Cert % Won Type Date Reason Closed Held Date of Votes for / Consent / (Win / Rep by Date Eligible Against Labor Directed Loss) Win Union Voters Org 1 Count 01 01-RC-022514 Johnson Controls, Inc. RC 12/29/2010 Certification of 3/8/2012 Devens 2/23/2011 15 9 5 AREA TRADES COUNCIL, A/W Directed LOSS Results IUOE LOCAL 877; PLUMBERS MA LOCAL 12, IBEW LOCAL 103; CARPENTERS LOCAL 51; PAI 01 01-RC-061888 M.V.M. -

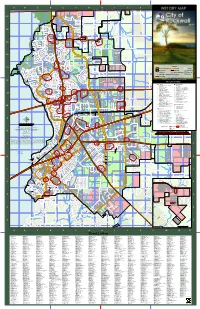

Dryzone Bufferzones F

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O Sands Lake N T L h E o m C A p R s o G n C B A COYOTE RUN r M a P n C R c N BREEZYHILL LN L ANNACADE RD E h E N K DR I CityH of Rockwall P L O LIM OLD MILLWOOD RD PRAIRIEVIEW LN D M NORTHSTAR RD 17 ER BIRDS 17 HILL DR LN NEST SENEY DR L LIFE SPRING DR A OL ND KETTEN DR D ZY M WILLOW PO BROOKE DR ILLW FARM LN OO RD DC IR HEATHER FALLS DR R N SMITH N RD FOX HALL DR D K LORIONDR N PLEASANT ACRES LN KING N RD A CALM B CREST DR CATTERICK DR COZY ECIR N D E A VIEW DR A C OAKHURST CT V ANN A R RALEIGH LN WINDHAM DR T H PLEASANT HOPKINS BLUFF DR O MERE DR R LEN CT N G WHITMAN DR PLEASANT D VISTA CAMERON LN BETTYST A LONE VIEW DR MARTY CIR DR L VIEW DR E L ALL ANGELSHILL LN CREST DR RUN DR GATEWICKDR RAVEN- N NOAH 16 DURHAM 16 HURST DR DR GE RD AM Crenshaw Lake SHENNENDOAH COUNTRY RID BER KIMBERLY LN CHESTNUT LN WILDBRIAR K CEDAR BLUFF DR N HUNTCLIFFE S CT LN SHENANDOAH LN O LAR LL HUNT LN L LN LONE DR CE DREWSBURYDR WINDSOR CREST DR ANNACADE RD WAY OLDMILLWOOD RD RLAN DR W WINDY A H JOHN N KINGBLVD T R S H I D BREEZYHILL LN S S BE DR HILL LN E FM 552 S I E P S S J PRINGLE LN VALLEYRED RUN ! E RIDGE CIR MEADOW R O SHANNON DR I HOLDENDR OCONNELL N R R I BOGGS G C C O E N CIR A E G E K L WOODED TRL V D S I ROYALRIDGE DR G A ! FAWN SKYVIEWLN R L R CLEAR MCKINZIE D H L I STATE HIGHWAY 66 E N ! TRL PHYLLIS LN A BLUFF DR G L FM 552 I D î LYDIALN R PL CIR H O A 89:|î E FM 552 H FM 552 DALTON RD R COBBLESTONE DR DISMORE DISMORE LN STONECREEK DR 0 T NORTHRIDGE LN P SADDLE HORN 7 A 3 B N ! 2 CLEAR TOM L G ! O CAVEN- GRANDVIEW DR ! 9 THUMB N L MEADOW î89:| C 4 KNOX H N B 5 G U DISH CT E PR 2365 L C ! V CT S.C.