Ghosts, Spies, and Grand- Mothers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apichatpong Weerasethakul

UNKNOWN FORCES: APICHATPONG WEERASETHAKUL April 18 – June 17, 2007 hold of and ask what I should do. I am consulting a fortune teller now for what the next film should be. She told me the main character (light skin, wide forehead), the locations (university, sports stadium, empty temple, mountain), and the elements (the moon and the water). RI: The backdrops of much of your work accentuate feelings of aloneness and isolation from others. Films like Tropical Malady (2004) and Worldly Desires (2005) traverse remote recesses of distant, even enchanted jungles. In FAITH (2006), you leave earth entirely in search of greater solitude in outer space. You seem interested in or at least drawn to obscure or enigmatic sites that have been left relatively unexplored, untouched, unimagined… AW: That’s what I got from the movies. When you are in a dark theater, your mind drifts and travels. In my hometown when I was growing up, there was nothing. The movie theater was a sanctuary where I was mostly addicted to spectacular and disaster films. Now, as a filmmaker, I am trying to search for similar feelings of wonder, of dreams. It’s quite a personal and isolated experience. Tropical Malady is more about a journey into one’s mind rather than Apichatpong Weerasethakul a real jungle. Or sometimes it is a feeling of “watching” movies. RI: Can you speak about your use of old tales and mythologies in your work? What significance do they hold for you? AW: It’s in the air. Thailand’s atmosphere is unique. It might be hard to understand for foreigners. -

Great Food, Great Stories from Korea

GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIE FOOD, GREAT GREAT A Tableau of a Diamond Wedding Anniversary GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS This is a picture of an older couple from the 18th century repeating their wedding ceremony in celebration of their 60th anniversary. REGISTRATION NUMBER This painting vividly depicts a tableau in which their children offer up 11-1541000-001295-01 a cup of drink, wishing them health and longevity. The authorship of the painting is unknown, and the painting is currently housed in the National Museum of Korea. Designed to help foreigners understand Korean cuisine more easily and with greater accuracy, our <Korean Menu Guide> contains information on 154 Korean dishes in 10 languages. S <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Tokyo> introduces 34 excellent F Korean restaurants in the Greater Tokyo Area. ROM KOREA GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES FROM KOREA The Korean Food Foundation is a specialized GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES private organization that searches for new This book tells the many stories of Korean food, the rich flavors that have evolved generation dishes and conducts research on Korean cuisine after generation, meal after meal, for over several millennia on the Korean peninsula. in order to introduce Korean food and culinary A single dish usually leads to the creation of another through the expansion of time and space, FROM KOREA culture to the world, and support related making it impossible to count the exact number of dishes in the Korean cuisine. So, for this content development and marketing. <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Western Europe> (5 volumes in total) book, we have only included a selection of a hundred or so of the most representative. -

국립중앙도서관 소장의 「Jusikbangmun (주식방문)」을 통해 본 조선 후기 음식에 대한 고찰

한국식생활문화학회지 31(6): 554-572, 2016 ISSN 1225-7060(Print) J. Korean Soc. Food Cult. 31(6): 554-572, 2016 ISSN 2288-7148(Online) 본 논문의 저작권은 한국식생활문화학회에 있음 . http://dx.doi.org/10.7318/KJFC/2016.31.6.554 Copyright © The Korean Society of Food Culture 국립중앙도서관 소장의 「Jusikbangmun (주식방문)」을 통해 본 조선 후기 음식에 대한 고찰 최 영 진* 가톨릭관동대학교 가정교육과 Study on Foods of 「Jusikbangmun」 from National Central Library Possession in the late Period of Joseon Dynasty Young-Jin Choi* Department of Home Economics, Catholic Kwandong University Abstract This study is a comparative study on a cookbook published in 1900s titled 「Jusikbangmun」, one of collections of the National Central Library, along with other cookery books in Joseon Dynasty in the late 1800s to early 1900s. 「Jusikbangmun」consists of 51 recipes, including 45 kinds of staple foods and six kinds of brews. More than 60% of the recipes deal with staple dishes and side-dishes, whereas the rest deal with ceremonial dishes and drinking. The 「Jusikbangmun」 applies a composite method of cooking from boiling and steaming to seasoning with oil spices. The ingredients are largely meats rather than vegetables, which is distinguished other cookery books in the Joseon Dynasty. Only 「Jusikbangmun」deals with such peculiar recipes as ‘Kanmagitang’, ‘Bookyengsumyentang’, ‘Jeryukpyen’, ‘Yangsopyen’, and ‘Dalgihye’. It is estimated that 「Jusikbangmun」 was published around the 1900s based on findings that 「Jusikbangmun」 is more similar with 「Buinpilgi」 and 「Joseonyorijebeop」 in the early 1900s than with 「Kyuhapchongseo」, 「Siyijenseo」and「Jusiksieui」in 1800s. Therefore,「Jusikbangmun」is a valuable resource, we can use understand the food culture of the late Joseon period. -

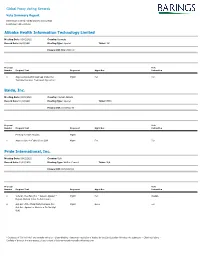

Global Proxy Voting Records

Global Proxy Voting Records Vote Summary Report Date range covered: 03/01/2021 to 03/31/2021 Location(s): All Locations Alibaba Health Information Technology Limited Meeting Date: 03/01/2021 Country: Bermuda Record Date: 02/23/2021 Meeting Type: Special Ticker: 241 Primary ISIN: BMG0171K1018 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction 1 Approve Revised Annual Cap Under the Mgmt For For Technical Services Framework Agreement Baidu, Inc. Meeting Date: 03/01/2021 Country: Cayman Islands Record Date: 01/28/2021 Meeting Type: Special Ticker: BIDU Primary ISIN: US0567521085 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction Meeting for ADR Holders Mgmt 1 Approve One-to-Eighty Stock Split Mgmt For For Pride International, Inc. Meeting Date: 03/01/2021 Country: USA Record Date: 12/01/2020 Meeting Type: Written Consent Ticker: N/A Primary ISIN: US74153QAJ13 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction 1 Vote On The Plan (For = Accept, Against = Mgmt For Abstain Reject; Abstain Votes Do Not Count) 2 Opt Out of the Third-Party Releases (For = Mgmt None For Opt Out, Against or Abstain = Do Not Opt Out) * Instances of "Do Not Vote" are normally owing to: - Share-blocking - temporary restriction of trading by the Sub-Custodian following vote submission - Client restrictions - Conflicts of Interest. For any queries, please contact [email protected] Global Proxy Voting Records Vote Summary Report Date range covered: 03/01/2021 to 03/31/2021 Location(s): All Locations The -

Delegates Guide

Delegates Guide 9–14 March, 2018 Cultural Partners Supported by Friends of Qumra Media Partner QUMRA DELEGATES GUIDE Qumra Programming Team 5 Qumra Masters 7 Master Class Moderators 14 Qumra Project Delegates 17 Industry Delegates 57 QUMRA PROGRAMMING TEAM Fatma Al Remaihi CEO, Doha Film Institute Director, Qumra Jaser Alagha Aya Al-Blouchi Quay Chu Anthea Devotta Qumra Industry Qumra Master Classes Development Qumra Industry Senior Coordinator Senior Coordinator Executive Coordinator Youth Programmes Senior Film Workshops & Labs Coordinator Senior Coordinator Elia Suleiman Artistic Advisor, Doha Film Institute Mayar Hamdan Yassmine Hammoudi Karem Kamel Maryam Essa Al Khulaifi Qumra Shorts Coordinator Qumra Production Qumra Talks Senior Qumra Pass Senior Development Assistant Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Film Programming Senior QFF Programme Manager Hanaa Issa Coordinator Animation Producer Director of Strategy and Development Deputy Director, Qumra Meriem Mesraoua Vanessa Paradis Nina Rodriguez Alanoud Al Saiari Grants Senior Coordinator Grants Coordinator Qumra Industry Senior Qumra Pass Coordinator Coordinator Film Workshops & Labs Coordinator Wesam Said Eliza Subotowicz Rawda Al-Thani Jana Wehbe Grants Assistant Grants Senior Coordinator Film Programming Qumra Industry Senior Assistant Coordinator Khalil Benkirane Ali Khechen Jovan Marjanović Chadi Zeneddine Head of Grants Qumra Industry Industry Advisor Film Programmer Ania Wojtowicz Manager Qumra Shorts Coordinator Film Training Senior Film Workshops & Labs Senior Coordinator -

The Lie Behind the Lie Detector

Te Lie Behind the Lie Detector 5th edition by George W. Maschke and Gino J. Scalabrini AntiPolygraph.org Te Lie Behind the Lie Detector Te Lie Behind the Lie Detector by George W. Maschke and Gino J. Scalabrini AntiPolygraph.org 5th edition Published by AntiPolygraph.org © 2000, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2018 by George W. Maschke and Gino J. Scalabrini. All rights reserved. Tis book is free for non- commercial distribution and use, provided that it is not altered. Typeset by George W. Maschke Dedication WE DEDICATE this book to the memory of our friend and mentor, Drew Campbell Richardson (1951–2016). Dr. Richardson took a courageous public stand against polygraph screening while serv- ing as the FBI’s senior scientific expert on polygraphy. Without the example of his courage in speaking truth to power without fear or favor, this book might never have been writen. We also note with sadness the passing of polygraph critics David Toreson Lykken (1928–2006) and John J. Furedy (1940– 2016), both of whom reviewed early drafs of the first edition of this book and provided valuable feedback. Contents Dedication …………………………………………………………………………….7 Contents ……………………………………………………………………………….8 Acknowledgments ……………………………………………………………….13 Foreword …………………………………………………………………………….14 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………..15 Chapter 1: On the Validity of Polygraphy ………………………………18 Polygraph Screening …………………………………………………………22 False Positives and the Base Rate Problem ………………………….25 Specific-Issue “Testing” ……………………………………………………..26 Te National Academy of Sciences Report -

Police Perjury: a Factorial Survey

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Police Perjury: A Factorial Survey Author(s): Michael Oliver Foley Document No.: 181241 Date Received: 04/14/2000 Award Number: 98-IJ-CX-0032 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. FINAL-FINAL TO NCJRS Police Perjury: A Factorial Survey h4ichael Oliver Foley A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Criminal Justice in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The City University of New York. 2000 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. I... I... , ii 02000 Michael Oliver Foley All Rights Reserved This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

The Jungle As Border Zone: the Aesthetics of Nature in the Work of Apichatpong Weerasethakul Boehler, Natalie

www.ssoar.info The jungle as border zone: the aesthetics of nature in the work of Apichatpong Weerasethakul Boehler, Natalie Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Boehler, N. (2011). The jungle as border zone: the aesthetics of nature in the work of Apichatpong Weerasethakul. ASEAS - Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 4(2), 290-304. https://doi.org/10.4232/10.ASEAS-4.2-6 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-286944 ASEAS 4(2) Aktuelle Südostasienforschung / Current Research on South-East Asia The Jungle as Border Zone: The Aesthetics of Nature in the Work of Apichatpong Weerasethakul Natalie Boehler1 University of Zürich, Switzerland Citation Boehler, N. (2011). The Jungle as Border Zone: The Aesthetics of Nature in the Work of Apichatpong Weera- sethakul. ASEAS - Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 4(2), 290-304. In Thai cinema, nature is often depicted as an opposition to the urban sphere, forming a contrast in ethical terms. This dualism is a recurring and central theme in Thai representations and an impor- tant carrier of Thainess (khwam pen Thai). -

VCE Second Language

Korean Second Language Victorian Certificate of Education Study Design Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority 2004 www.theallpapers.comJanuary 2013 COVER ARTWORK WAS SELECTED FROM THE TOP ARTS EXHIBITION. COPYRIGHT REMAINS THE PROPERTY OF THE ARTIST. Latoya BARTON Tarkan ERTURK The sunset (detail) Visage (detail) from a series of twenty-four 201.0 x 170.0 cm 9.0 x 9.0 cm each, oil on board synthetic polymer paint, on cotton duck Liana RASCHILLA Nigel BROWN Teapot from the Crazy Alice set Untitled physics (detail) 19.0 x 22.0 x 22.0 cm 90.0 x 440.0 x 70.0 cm earthenware, clear glaze. lustres composition board, steel, loudspeakers, CD player, amplifier, glass Kate WOOLLEY Chris ELLIS Sarah (detail) Tranquility (detail) 76.0 x 101.5 cm, oil on canvas 35.0 x 22.5 cm gelatin silver photograph Christian HART Kristian LUCAS Within without (detail) Me, myself, I and you (detail) digital film, 6 minutes 56.0 x 102.0 cm oil on canvas Merryn ALLEN Ping (Irene VINCENT) Japanese illusions (detail) Boxes (detail) centre back: 74.0 cm, waist (flat): 42.0 cm colour photograph polyester cotton James ATKINS Tim JOINER Light cascades (detail) 14 seconds (detail) three works, 32.0 x 32.0 x 5.0 cm each digital film, 1.30 minutes glass, flourescent light, metal Lucy McNAMARA Precariously (detail) 156.0 x 61.0 x 61.0 cm painted wood, oil paint, egg shells, glue, stainless steel wire Accredited by the Victorian Qualifications Authority 41a St Andrews Place, East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Developed and published by the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority 41 St Andrews Place, East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 This completely revised and reaccredited edition published 2004. -

166-90-06 Tel: +38(063)804-46-48 E-Mail: [email protected] Icq: 550-846-545 Skype: Doowopteenagedreams Viber: +38(063)804-46-48 Web

tel: +38(097)725-56-34 tel: +38(099)166-90-06 tel: +38(063)804-46-48 e-mail: [email protected] icq: 550-846-545 skype: doowopteenagedreams viber: +38(063)804-46-48 web: http://jdream.dp.ua CAT ORDER PRICE ITEM CNF ARTIST ALBUM LABEL REL G-049 $60,37 1 CD 19 Complete Best Ao&haru (jpn) CD 09/24/2008 G-049 $57,02 1 SHMCD 801 Latino: Limited (jmlp) (ltd) (shm) (jpn) CD 10/02/2015 G-049 $55,33 1 CD 1975 1975 (jpn) CD 01/28/2014 G-049 $153,23 1 SHMCD 100 Best Complete Tracks / Various (jpn)100 Best... Complete Tracks / Various (jpn) (shm) CD 07/08/2014 G-049 $48,93 1 CD 100 New Best Children's Classics 100 New Best Children's Classics AUDIO CD 07/15/2014 G-049 $40,85 1 SHMCD 10cc Deceptive Bends (shm) (jpn) CD 02/26/2013 G-049 $70,28 1 SHMCD 10cc Original Soundtrack (jpn) (ltd) (jmlp) (shm) CD 11/05/2013 G-049 $55,33 1 CD 10-feet Vandalize (jpn) CD 03/04/2008 G-049 $111,15 1 DVD 10th Anniversary-fantasia-in Tokyo Dome10th Anniversary-fantasia-in/... Tokyo Dome / (jpn) [US-Version,DVD Regio 1/A] 05/24/2011 G-049 $37,04 1 CD 12 Cellists Of The Berliner PhilharmonikerSouth American Getaway (jpn) CD 07/08/2014 G-049 $51,22 1 CD 14 Karat Soul Take Me Back (jpn) CD 08/21/2006 G-049 $66,17 1 CD 175r 7 (jpn) CD 02/22/2006 G-049 $68,61 2 CD/DVD 175r Bremen (bonus Dvd) (jpn) CD 04/25/2007 G-049 $66,17 1 CD 175r Bremen (jpn) CD 04/25/2007 G-049 $48,32 1 CD 175r Melody (jpn) CD 09/01/2004 G-049 $45,27 1 CD 175r Omae Ha Sugee (jpn) CD 04/15/2008 G-049 $66,92 1 CD 175r Thank You For The Music (jpn) CD 10/10/2007 G-049 $48,62 1 CD 1966 Quartet Help: Beatles Classics (jpn) CD 06/18/2013 G-049 $46,95 1 CD 20 Feet From Stardom / O. -

Number 2 2010 Tribute to Dr. Zo Zayong

NUMBER 2 2010 TRIBUTE TO DR. ZO ZAYONG KOREAN ART SOCIETY JOURNAL NUMBER 2 2010 Publisher: Robert Turley, President of Korean Art Society and Korean Art and Antiques CONTENTS page About the Authors…………………………………………..…………………...…..…….3 Acknowledgment……….…………………………….…….…………………………..….4 Publisher’s Greeting…...…………………………….…….…………………………..….5 Memories of Zo Zayong by Dr. Theresa Ki-ja Kim.…………………………...….….6-9 Dr. Zo Zayong, A Great Korean by David Mason………..…………………….…...10-20 Great Antique Sansin Paintings from Zo Zayong’s Emille Museum…………....21-28 “New” Sansin Icons that Zo Zayong Painted Himself……………………........….29-34 Zo Zayong Annual Memorial Ceremonies at Yeolsu Yoon’s Gahoe Museum..35-39 Dr. Zo’s Old Village Movement by Lauren Deutsch……….…….……………..….40-56 Books by Zo Zayong…..…………………………….…….………………………......….57 KAS Journal Letters Column………………………………………………………..…58-59 Korean Art Society Events……………………………………………………………...60-62 Korean Art Society Press……………………………………………………………….63-67 Join the Korean Art Society……………...………….…….……………………...…..….68 About the Authors: David Mason is the author of Spirit of the Mountains, Korea’s SAN-SHIN and Traditions of Mountain Worship (Hollym, 1999), a well researched and beautifully illustrated book that is highly recommended reading. He is also the creator of the exhaustive San-shin website (www.san-shin.org) and the enlightening Zozayong website (www.zozayong.com) on the legendary champion of Korean folk art and culture, Zo Zayong. Both of these sites contain a wealth of information not available elsewhere and make for rewarding browsing. [email protected] Lauren Deutsch is the executive producer and director of Pacific Rim Arts (www.pacificrimarts.org) through which she undertakes culturally-focused projects, including festivals, performances, exhibitions, conferences and media (public radio and television) outreach. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays.