Occasionality: a Theory of Literary Exchange Between Us and China in the Nineteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

43Rd ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS Tokyo (JPN) 7 16 October 2011

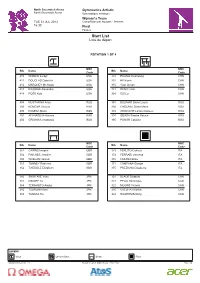

43rd ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS Tokyo (JPN) 7 16 October 2011 START LIST WOMEN'S QUALIFICATION SUBDIVISION 6 OF 10 ROTATION 1 OF 4 SAT 8 OCT 2011 11:30 NOC NOC Bib Name Bib Name Code Code 725 EUM Eunhui KOR 774 BELAK Teja SLO 724 PARK Kyung Jin KOR 776 NOVAK Fiona SLO 723 HEO Seon Mi KOR 772 GOLOB Sasa SLO 727 KIM Doyoung KOR * 773 KAMNIKAR Ivana SLO 722 JO Hyunjoo KOR * 771 SAJN Adela SLO 726 PARK Ji Yeon KOR 775 HORVAT Carmen SLO NOC NOC Bib Name Bib Name Code Code 537 KARMAKAR Dipa IND 636 JIANG Yuyuan CHN 631 HUANG Qiushuang CHN 632 YAO Jinnan CHN 634 SUI Lu CHN 633 TAN Sixin CHN 635 HE Kexin CHN Note: Gymnasts marked by an asterisk (“*”) will perform two vaults Legend: Vault Uneven Bars Beam Floor GAW099900_51B 1.0 Report Created FRI 7 OCT 2011 14:54 Longines Official Results Provider Page 21/40 43rd ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS Tokyo (JPN) 7 16 October 2011 START LIST WOMEN'S QUALIFICATION SUBDIVISION 6 OF 10 ROTATION 2 OF 4 SAT 8 OCT 2011 11:52 NOC NOC Bib Name Bib Name Code Code 634 SUI Lu CHN 726 PARK Ji Yeon KOR 636 JIANG Yuyuan CHN 724 PARK Kyung Jin KOR 631 HUANG Qiushuang CHN 722 JO Hyunjoo KOR 632 YAO Jinnan CHN 725 EUM Eunhui KOR 633 TAN Sixin CHN 723 HEO Seon Mi KOR 635 HE Kexin CHN 727 KIM Doyoung KOR NOC NOC Bib Name Bib Name Code Code 773 KAMNIKAR Ivana SLO 549 FARAH ANN Abdul Hadi MAS 774 BELAK Teja SLO 776 NOVAK Fiona SLO 772 GOLOB Sasa SLO 771 SAJN Adela SLO 775 HORVAT Carmen SLO Note: Gymnasts marked by an asterisk (“*”) will perform two vaults Legend: Vault Uneven Bars Beam Floor -

© 2013 Yi-Ling Lin

© 2013 Yi-ling Lin CULTURAL ENGAGEMENT IN MISSIONARY CHINA: AMERICAN MISSIONARY NOVELS 1880-1930 BY YI-LING LIN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral committee: Professor Waïl S. Hassan, Chair Professor Emeritus Leon Chai, Director of Research Professor Emeritus Michael Palencia-Roth Associate Professor Robert Tierney Associate Professor Gar y G. Xu Associate Professor Rania Huntington, University of Wisconsin at Madison Abstract From a comparative standpoint, the American Protestant missionary enterprise in China was built on a paradox in cross-cultural encounters. In order to convert the Chinese—whose religion they rejected—American missionaries adopted strategies of assimilation (e.g. learning Chinese and associating with the Chinese) to facilitate their work. My dissertation explores how American Protestant missionaries negotiated the rejection-assimilation paradox involved in their missionary work and forged a cultural identification with China in their English novels set in China between the late Qing and 1930. I argue that the missionaries’ novelistic expression of that identification was influenced by many factors: their targeted audience, their motives, their work, and their perceptions of the missionary enterprise, cultural difference, and their own missionary identity. Hence, missionary novels may not necessarily be about conversion, the missionaries’ primary objective but one that suggests their resistance to Chinese culture, or at least its religion. Instead, the missionary novels I study culminate in a non-conversion theme that problematizes the possibility of cultural assimilation and identification over ineradicable racial and cultural differences. -

Darán Jóvenes Panistas 30 Mil Votos a Martha

Gómez Mont: E.U. Women’s Championship PRETENDEN LA SEGURIDAD Logra OCHoa CAMBIAR colocarse en sexta NO SE NEGOCIA SISTEMA posición NACIONAL A 10 DE SALUD DEPORTES C 1 INTERNACIONAL C 11 Año 56. No. 18,564 $6.00 Colima, CoIima Viernes 6 de Marzo de 2009 www.diariodecolima.com En Los Asmoles OtrosEstaban atados de las manos y con vendasdos ejecutados en los ojos; nuevamente los sicarios dejan mensaje; van siete asesinatos en menos de un mes Sergio URIBE ALVARADO 30 y 35 años de edad; complexión delgada, tez morena clara, de 1.60 Dos hombres fueron ejecutados la metros de estatura, pelo negro cor- madrugada de ayer en el camino to, lampiño; vestía pantalón color sacacosechas Los Asmoles-Monte azul de mezclilla, cinto color café, Grande, frente al cerro denomina- playera tipo sport color blanco con do “El Gallo”, estaban atados de las franjas a los costados color negro y manos y también tenían vendados calzaba tenis blanco con negro. los ojos; uno de ellos tenía pegada En el libramiento Los Limones, a su pecho una cartulina color aproximadamente a 1 kilómetro de blanco con la leyenda: “Esto me la autopista Colima-Manzanillo, paso por andar de chapulin y no se localizó una camioneta marca aliniarme como la gente”. Toyota, tipo Hilux, color blanco, Uno de los hoy occisos era modelo 2007, con placas de circu- Carlos César Salazar Sánchez, lación FE-35693, donde viajaban quien tenía su domicilio en los finados. el poblado de Ticuicitán. Fue Un hermano de Carlos César, consignado el 14 de septiembre de de nombre Ignacio Salazar Sán- 2003 por el agente del Ministerio chez, es trabajador del ayunta- Público Federal por delitos contra miento de Colima. -

The Overture of Peking Pronunciation's Victory

The Journal of Chinese Linguistics vol.48, no.2 (June 2020): 402–437 © 2020 by the Journal of Chinese Linguistics. ISSN 0091-3723/ The overture of Peking pronunciation’s victory: The first published Peking orthography. By Ju Song. All rights reserved. s THE OVERTURE OF PEKING PRONUNCIATION’S al ri VICTORY: THE FIRST PUBLISHED PEKING te a ORTHOGRAPHY M Ju Song d Fudan University, Shanghai te gh ri py ABSTRACT o : C Thomas Francis Wade (1818–1895) and his Wade-Gilesss System have been credited with promoting the victory of Pekinge pronunciation as the Pr standard Mandarin. However, the firstg Peking orthography was not published by him, but another Britishon consular official, Thomas Taylor Meadows (1815–1868), in his bookK Desultory Notes (1847). In the present g paper the content and value of othisn orthography are examined by comparing Meadows and his contemporaries’,H especially Wade’s, attitudes and treatment towards Pekingf Mandarin and a uniform Chinese transcription o system, with specific treferencey to the development of Peking Mandarin in th i 19 century. It demonstratesrs that Wade adopted Meadows’s opinion on the significance of vPekinge pronunciation, and his system was also influenced ni by Meadows’s U in many aspects. This study illuminates that Meadows’ orthography,se as a first try of an exclusive transcription system for Peking ne hi CAcknowledgments I would like to express my appreciation to Professor Jie Fu and e Wenkan Xu for providing the initial inspiration for this project. Special gratitude is owed to h Professor Victor H. Mair and Keiichi Uchida, who both read the draft of the manuscript and T offered feedback. -

Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881

China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 The East India Company’s steamship Nemesis and other British ships engaging Chinese junks in the Second Battle of Chuenpi, 7 January 1841, during the first opium war. (British Library) ABOUT THE ARCHIVE China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 is digitised from the FO 17 series of British Foreign Office Files—Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence before 1906, China— held at the National Archives, UK, providing a vast and significant primary source for researching every aspect of Chinese-British relations during the nineteenth century, ranging from diplomacy to trade, economics, politics, warfare, emigration, translation and law. This first part includes all content from FO 17 volumes 1–872. Source Library Number of Images The National Archives, UK Approximately 532,000 CONTENT From Lord Amherst’s mission at the start of the nineteenth century, through the trading monopoly of the Canton System, and the Opium Wars of 1839–1842 and 1856–1860, Britain and other foreign powers gradually gained commercial, legal, and territorial rights in China. Imperial China and the West provides correspondence from the Factories of Canton (modern Guangzhou) and from the missionaries and diplomats who entered China in the early nineteenth century, as well as from the envoys and missions sent to China from Britain and the later legation and consulates. The documents comprising this collection include communications to and from the British legation, first at Hong Kong and later at Peking, and British consuls at Shanghai, Amoy (Xiamen), Swatow (Shantou), Hankow (Hankou), Newchwang (Yingkou), Chefoo (Yantai), Formosa (Taiwan), and more. -

Low Carbon Development Roadmap for Jilin City Jilin for Roadmap Development Carbon Low Roadmap for Jilin City

Low Carbon Development Low Carbon Development Roadmap for Jilin City Roadmap for Jilin City Chatham House, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Energy Research Institute, Jilin University, E3G March 2010 Chatham House, 10 St James Square, London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0)20 7957 5700 E: [email protected] F: +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org.uk Charity Registration Number: 208223 Low Carbon Development Roadmap for Jilin City Chatham House, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Energy Research Institute, Jilin University, E3G March 2010 © Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2010 Chatham House (the Royal Institute of International Affairs) is an independent body which promotes the rigorous study of international questions and does not express opinion of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publishers. Chatham House 10 St James’s Square London, SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0) 20 7957 5700 F: +44 (0) 20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org.uk Charity Registration No. 208223 ISBN 978 1 86203 230 9 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Cover image: factory on the Songhua River, Jilin. Reproduced with kind permission from original photo, © Christian Als, -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 123 2nd International Conference on Education, Sports, Arts and Management Engineering (ICESAME 2017) Study on the Contribution of Xiling's Poetry to Poetry Flourished in Earlier Qing Dynasty Liping Gu The Engineering & Technical College of Chengdu University of Technology, Leshan, Sichuan, 614000 Keywords: Xiling Poetry, Poetry Flourished, Qing Dynasty Abstract. At the beginning of the Qing Dynasty, Xiling language refers to the late Ming and early Qing Dynasty in Xiling a word activities of the word group, including Xiling capital of the poet, including the official travel in Xiling’s poetry, is a geographical, The family, the teacher as a link to the end of the alliance as an opportunity, while infiltration Xiling heavy word tradition, in the late Ming Dynasty poetry specific poetry language formation in the group of people. They are more rational and objective theory, especially emphasizing the essence of the word speculation, pay attention to the word rhyme and the creation of the law of the summary, whether it is theory or creation, the development of the Qing Dynasty have far-reaching impact. In short, the late Ming and early Qing Dynasty Xiling language in the word from the yuan, the decline since the turn of the Qing Dynasty to the revival of the evolution of this process is a can not be ignored. Introduction The formation and development of the Xiling School are inseparable from the development of the same language. Many people regard the Western Cold School as the rise of the cloud and even as part of the cloud. -

A Book Lover's Journey: Literary Archaeology and Bibliophilia in Tim

Verbeia Número 1 ISSN 2444-1333 Leonor María Martínez Serrano A Book Lover’s Journey: Literary Archaeology and Bibliophilia in Tim Bowling’s In the Suicide’s Library Leonor María Martínez Serrano Universidad de Córdoba [email protected] Resumen Nativo de la costa occidental de Canadá, Tim Bowling es uno de los autores canadienses más aclamados. Su obra In the Suicide’s Library. A Book Lover’s Journey (2010) explora cómo un solo objeto —un ejemplar gastado ya por el tiempo de Ideas of Order de Wallace Stevens que se encuentra en una biblioteca universitaria— es capaz de hacer el pasado visible y tangible en su pura materialidad. En la solapa delantera del libro de Stevens, Bowling descubre la elegante firma de su anterior dueño, Weldon Kees, un oscuro poeta norteamericano que puso fin a su vida saltando al vacío desde el Golden Gate Bridge. El hallazgo de este ejemplar autografiado de la obra maestra de Stevens marca el comienzo de una meditación lírica por parte de Bowling sobre los libros como objetos de arte, sobre el suicidio, la relación entre padres e hijas, la historia de la imprenta y la bibliofilia, a la par que lleva a cabo una suerte de arqueología del pasado literario de los Estados Unidos con una gran pericia literaria y poética vehemencia. Palabras clave: Tim Bowling, bibliofilia, narrativa, arqueología del saber, vestigio. Abstract A native of the Canadian West Coast, Tim Bowling is widely acclaimed as one of the best living Canadian authors. His creative work entitled In the Suicide’s Library. A Book Lover’s Journey (2010) explores how a single object —a tattered copy of Wallace Stevens’s Ideas of Order that he finds in a university library— can render the past visible and tangible in its pure materiality. -

Book of Abstracts

PICES Seventeenth Annual Meeting Beyond observations to achieving understanding and forecasting in a changing North Pacific: Forward to the FUTURE North Pacific Marine Science Organization October 24 – November 2, 2008 Dalian, People’s Republic of China Contents Notes for Guidance ...................................................................................................................................... v Floor Plan for the Kempinski Hotel......................................................................................................... vi Keynote Lecture.........................................................................................................................................vii Schedules and Abstracts S1 Science Board Symposium Beyond observations to achieving understanding and forecasting in a changing North Pacific: Forward to the FUTURE......................................................................................................................... 1 S2 MONITOR/TCODE/BIO Topic Session Linking biology, chemistry, and physics in our observational systems – Present status and FUTURE needs .............................................................................................................................. 15 S3 MEQ Topic Session Species succession and long-term data set analysis pertaining to harmful algal blooms...................... 33 S4 FIS Topic Session Institutions and ecosystem-based approaches for sustainable fisheries under fluctuating marine resources .............................................................................................................................................. -

Start List Liste De Départ

North Greenwich Arena Gymnastics Artistic North Greenwich Arena Gymnastique artistique Women's Team TUE 31 JUL 2012 Compétition par équipes - femmes 16:30 Final Finales Start List Liste de départ ROTATION 1 OF 4 NOC NOC Bib Name Bib Name Code Code 415 WIEBER Jordyn USA 333 HUANG Qiushuang CHN 411 DOUGLAS Gabrielle USA 332 HE Kexin CHN 412 MARONEY Mc Kayla USA 335 YAO Jinnan CHN 413 RAISMAN Alexandra USA 331 DENG Linlin CHN 414 ROSS Kyla USA 334 SUI Lu CHN 404 MUSTAFINA Aliya RUS 391 BULIMAR Diana Laura ROU 403 KOMOVA Victoria RUS 392 CHELARU Diana Maria ROU 405 PASEKA Maria RUS 393 IORDACHE Larisa Andreea ROU 401 AFANASEVA Kseniia RUS 394 IZBASA Sandra Raluca ROU 402 GRISHINA Anastasia RUS 395 PONOR Catalina ROU NOC NOC Bib Name Bib Name Code Code 351 CAIRNS Imogen GBR 373 FERLITO Carlotta ITA 352 PINCHES Jennifer GBR 374 FERRARI Vanessa ITA 355 WHELAN Hannah GBR 372 FASANA Erika ITA 353 TUNNEY Rebecca GBR 371 CAMPANA Giorgia ITA 354 TWEDDLE Elizabeth GBR 375 PREZIOSA Elisabetta ITA 382 SHINTAKE Yuko JPN 321 BLACK Elsabeth CAN 381 MINOBE Yu JPN 323 PEGG Dominique CAN 384 TERAMOTO Asuka JPN 322 MOORS Victoria CAN 385 TSURUMI Koko JPN 325 VACULIK Kristina CAN 383 TANAKA Rie JPN 324 ROGERS Brittany CAN LEGEND Vault Uneven Bars Beam Floor GAW400101_C51D 1.0 Report Created MON 30 JUL 2012 19:47 Page 1/4 North Greenwich Arena Gymnastics Artistic North Greenwich Arena Gymnastique artistique Women's Team TUE 31 JUL 2012 Compétition par équipes - femmes 16:58 Final Finales Start List Liste de départ ROTATION 2 OF 4 NOC NOC Bib Name Bib Name Code -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Uncertain Satire in Modern Chinese Fiction and Drama: 1930-1949 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Xi Tian August 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Perry Link, Chairperson Dr. Paul Pickowicz Dr. Yenna Wu Copyright by Xi Tian 2014 The Dissertation of Xi Tian is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Uncertain Satire in Modern Chinese Fiction and Drama: 1930-1949 by Xi Tian Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Comparative Literature University of California, Riverside, August 2014 Dr. Perry Link, Chairperson My dissertation rethinks satire and redefines our understanding of it through the examination of works from the 1930s and 1940s. I argue that the fluidity of satiric writing in the 1930s and 1940s undermines the certainties of the “satiric triangle” and gives rise to what I call, variously, self-satire, self-counteractive satire, empathetic satire and ambiguous satire. It has been standard in the study of satire to assume fixed and fairly stable relations among satirist, reader, and satirized object. This “satiric triangle” highlights the opposition of satirist and satirized object and has generally assumed an alignment by the reader with the satirist and the satirist’s judgments of the satirized object. Literary critics and theorists have usually shared these assumptions about the basis of satire. I argue, however, that beginning with late-Qing exposé fiction, satire in modern Chinese literature has shown an unprecedented uncertainty and fluidity in the relations among satirist, reader and satirized object. -

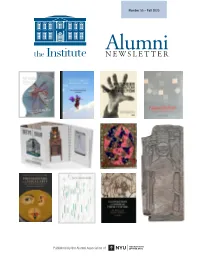

Institute of Fine Arts Alumni Newsletter, Number 55, Fall 2020

Number 55 – Fall 2020 NEWSLETTERAlumni PatriciaEichtnbaumKaretzky andZhangEr Neoclasicos rnE'-RTISTREINVENTiD,1~1-1= THEME""'lLC.IIEllMNICOLUCTION MoMA Ano M. Franco .. ..H .. •... 1 .1 e-i =~-:.~ CALLi RESPONSE Nyu THE INSTITUTE Published by the Alumni Association of II IOF FINE ARTS 1 Contents Letter from the Director In Memoriam ................. .10 The Year in Pictures: New Challenges, Renewed Commitments, Alumni at the Institute ..........16 and the Spirit of Community ........ .3 Iris Love, Trailblazing Archaeologist 10 Faculty Updates ...............17 Conversations with Alumni ....... .4 Leatrice Mendelsohn, Alumni Updates ...............22 The Best Way to Get Things Done: Expert on Italian Renaissance An Interview with Suzanne Deal Booth 4 Art Theory 11 Doctors of Philosophy Conferred in 2019-2020 .................34 The IFA as a Launching Pad for Seventy Nadia Tscherny, Years of Art-Historical Discovery: Expert in British Art 11 Master of Arts and An Interview with Jack Wasserman 6 Master of Science Dual-Degrees Dora Wiebenson, Conferred in 2019-2020 .........34 Zainab Bahrani Elected to the American Innovative, Infuential, and Academy of Arts and Sciences .... .8 Prolifc Architectural Historian 14 Masters Degrees Conferred in 2019-2020 .................34 Carolyn C Wilson Newmark, Noted Scholar of Venetian Art 15 Donors to the Institute, 2019-2020 .36 Institute of Fine Arts Alumni Association Offcers: Alumni Board Members: Walter S. Cook Lecture Susan Galassi, Co-Chair President Martha Dunkelman [email protected] and William Ambler [email protected] Katherine A. Schwab, Co-Chair [email protected] Matthew Israel [email protected] [email protected] Yvonne Elet Vice President Gabriella Perez Derek Moore Kathryn Calley Galitz [email protected] Debra Pincus [email protected] Debra Pincus Gertje Utley Treasurer [email protected] Newsletter Lisa Schermerhorn Rebecca Rushfeld Reva Wolf, Editor Lisa.Schermerhorn@ [email protected] [email protected] kressfoundation.org Katherine A.