Broadcasting Authority of Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Independent Productions Annual Report 2020

Independent Productions Annual Report 2020 CONTENTS Introduction 2 The Year in Review: – Television 4 – Radio 16 Other Funding 19 Other Support Activities 20 Corporate Governance 20 Financial and Commissioning Review 21 Independent Accountants’ Report 24 Schedules 25 RTÉ INDEPENDENT PRODUCTIONS ANNUAL REPORT 2020 1 INTRODUCTION From lockdowns to working from home and remote learning due to the Covid-19 pandemic restrictions, 2020 was a challenging year for everyone. As audience needs changed and evolved, RTÉ, together with the independent sector, rose to the challenge to ensure that quality Irish content was produced to inform, educate and entertain. From factual to entertainment, lifestyle, cláracha gaelige, drama, comedy and young people’s, the sector responded to unprecedented changes to daily life in Ireland and across the world to produce relevant and distinctive content. Audiences in Ireland connected with Irish content in increasing numbers across all genres, with RTÉ’s all-day share of TV viewing increasing by 1.7% to 27.2%1. RTÉ delivered 43 of the top 50 programmes on Irish television in 2020, with 14 being produced by the independent sector. Independent productions such as Ireland on Call and RTÉ’s Home School Hub played a pivotal role in meeting new audience needs and complemented News & Current Affairs content across TV, online and radio. As well as creating innovative new content and formats to meet these needs, the independent sector demonstrated great agility by adapting production models to comply with public health advice and restrictions. Series such as Ireland’s Fittest Family and Operation Transformation used best-practice production methods to ensure their safe return to screens, while new programming such as Gardening Together with Diarmuid Gavin, No Place Like Home and Open for Business reflected shifts in audience lifestyle and needs during the pandemic. -

Panel One Biographies

‘The future of media: experience, models, practice’ 6 May 2021 Panel One: The Irish Experience A discussion on the Irish experience in relation to broadcasting. Particular attention will be given to the independent broadcasting sector, local and national journalism and the media experience of minorities living in Ireland. 14:00 Welcome: Brian MacCraith MRIA, Chair, The Future of Media Commission 14:05 Chair’s introductions: Hugh Linehan, The Irish Times 14:10 Panellists’ introductory remarks: • Larry Bass, CEO ShinAwiL Productions • Rosemary Day, Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick • Bashir Otukoya, Dublin City University • Jane Suiter, Dublin City University 14:35 Panel discussion and audience Q&A 15:00 Panel one ends Hugh Linehan is the is Arts and Culture Editor at the Irish Times where he also presents the weekly Inside Politics podcast. Larry Bass, CEO and Executive Producer: Founder of ShinAwiL the producers of: Dancing With The Stars, The Voice of Ireland, The Apprentice, Dragons’ Den, MasterChef Ireland, Popstars and Home of the Year. Also now TV Drama including MISS SCARLET & THE DUKE. Larry has also Chaired: Screen Producers Ireland (SPI), Cabinteely F.C., Screen Skills Ireland. He served on the Boards of the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland (BAI), Screen Ireland, Entertainment Masterclass and The International Quorum of Motion Picture Producers. He has also sat on juries for the International Emmys, Rose d’Or, BANFF and Real Screen Television Awards. Larry has guest lectured at DIT Dublin, IADT Dublin, MipTV and MIPCOM, SPAA Australia and Entertainment Masterclass. Rosemary Day is the Head of Department of Media and Communication Studies and at Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick. -

Rté Independent Productions Annual Report 2020 1 Introduction

Independent Productions Annual Report 2020 CONTENTS Introduction 2 The Year in Review: – Television 4 – Radio 16 Other Funding 19 Other Support Activities 20 Corporate Governance 20 Financial and Commissioning Review 21 Independent Accountants’ Report 24 Schedules 25 RTÉ INDEPENDENT PRODUCTIONS ANNUAL REPORT 2020 1 INTRODUCTION From lockdowns to working from home and remote learning due to the Covid-19 pandemic restrictions, 2020 was a challenging year for everyone. As audience needs changed and evolved, RTÉ, together with the independent sector, rose to the challenge to ensure that quality Irish content was produced to inform, educate and entertain. From factual to entertainment, lifestyle, cláracha gaelige, drama, comedy and young people’s, the sector responded to unprecedented changes to daily life in Ireland and across the world to produce relevant and distinctive content. Audiences in Ireland connected with Irish content in increasing numbers across all genres, with RTÉ’s all-day share of TV viewing increasing by 1.7% to 27.2%1. RTÉ delivered 43 of the top 50 programmes on Irish television in 2020, with 14 being produced by the independent sector. Independent productions such as Ireland on Call and RTÉ’s Home School Hub played a pivotal role in meeting new audience needs and complemented News & Current Affairs content across TV, online and radio. As well as creating innovative new content and formats to meet these needs, the independent sector demonstrated great agility by adapting production models to comply with public health advice and restrictions. Series such as Ireland’s Fittest Family and Operation Transformation used best-practice production methods to ensure their safe return to screens, while new programming such as Gardening Together with Diarmuid Gavin, No Place Like Home and Open for Business reflected shifts in audience lifestyle and needs during the pandemic. -

GOLD Package Channel & VOD List

GOLD Package Channel & VOD List: incl Entertainment & Video Club (VOD), Music Club, Sports, Adult Note: This list is accurate up to 1st Aug 2018, but each week we add more new Movies & TV Series to our Video Club, and often add additional channels, so if there’s a channel missing you really wanted, please ask as it may already have been added. Note2: This list does NOT include our PLEX Club, which you get FREE with GOLD and PLATINUM Packages. PLEX Club adds another 500+ Movies & Box Sets, and you can ‘request’ something to be added to PLEX Club, and if we can source it, your wish will be granted. ♫: Music Choice ♫: Music Choice ♫: Music Choice ALTERNATIVE ♫: Music Choice ALTERNATIVE ♫: Music Choice DANCE EDM ♫: Music Choice DANCE EDM ♫: Music Choice Dance HD ♫: Music Choice Dance HD ♫: Music Choice HIP HOP R&B ♫: Music Choice HIP HOP R&B ♫: Music Choice Hip-Hop And R&B HD ♫: Music Choice Hip-Hop And R&B HD ♫: Music Choice Hit HD ♫: Music Choice Hit HD ♫: Music Choice HIT LIST ♫: Music Choice HIT LIST ♫: Music Choice LATINO POP ♫: Music Choice LATINO POP ♫: Music Choice MC PLAY ♫: Music Choice MC PLAY ♫: Music Choice MEXICANA ♫: Music Choice MEXICANA ♫: Music Choice Pop & Country HD ♫: Music Choice Pop & Country HD ♫: Music Choice Pop Hits HD ♫: Music Choice Pop Hits HD ♫: Music Choice Pop Latino HD ♫: Music Choice Pop Latino HD ♫: Music Choice R&B SOUL ♫: Music Choice R&B SOUL ♫: Music Choice RAP ♫: Music Choice RAP ♫: Music Choice Rap 2K HD ♫: Music Choice Rap 2K HD ♫: Music Choice Rock HD ♫: Music Choice -

Eir Sport Rugby Presenters

Eir Sport Rugby Presenters Henrik never hobnobbed any Arno blobbing proficiently, is Giordano pump-action and word-blind enough? Inflectionless Irving share that revocableness resubmits pardy and recombines frumpishly. Duncan bristled zigzag if compensatory Shelley underpropped or forwent. The eir sport presenters and BT Sport Included in Sky's Sports Extra package at 10 a following for sure first six months and 20 thereafter for existing Sky customers For non-Sky customers it's 17 per base for the stop six months and 34 thereafter far From the brew if this season BT Sport will show 52 live Premier League matches. 'You cite only use 10 of oriental research' Tommy Bowe. Classroom Of The Elite Volume 4. The co-commentator on eir sport was Liam Toland the former player. Get all 7 Sky Sports channels for 1999 a ring for 6 months with vegetation a 1 month min contract Includes Golf Tennis Rugby Premier League more. Now including access drive the eir sport and BT sport pack Jul 05 2016 Eir Sport. Does Setanta sports still exist? DARTS European Championship eir Sport 1 and ITV4 1245 and 1900. Sky Virgin Media UK Virgin Media Ireland YouView BTTalkTalk eir TV Expected to. Tommy Bowe will present eir sport's PRO14 rugby coverage. Now when eir sport announced last August that Tommy Bowe would. TV's old pros are not tackling rugby's big issues Ireland The. If you aren't an eir broadband customer and healthcare like there sign up now you can tow so by visiting the eir Broadband page on bonkersie Sky Sky Broadband customers can imagine to eir Sport for your average monthly cost of 175 Note telling you'll need the Sky viewing card urge to stride up. -

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List Australia FOX Sport 502 FOX LEAGUE HD Australia FOX Sport 504 FOX FOOTY HD Australia 10 Bold Australia SBS HD Australia SBS Viceland Australia 7 HD Australia 7 TV Australia 7 TWO Australia 7 Flix Australia 7 MATE Australia NITV HD Australia 9 HD Australia TEN HD Australia 9Gem HD Australia 9Go HD Australia 9Life HD Australia Racing TV Australia Sky Racing 1 Australia Sky Racing 2 Australia Fetch TV Australia Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Rugby League 1 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 2 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 3 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 1HD Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 2HD Australia -

TV & Radio Channels Astra 2 UK Spot Beam

UK SALES Tel: 0345 2600 621 SatFi Email: [email protected] Web: www.satfi.co.uk satellite fidelity Freesat FTA (Free-to-Air) TV & Radio Channels Astra 2 UK Spot Beam 4Music BBC Radio Foyle Film 4 UK +1 ITV Westcountry West 4Seven BBC Radio London Food Network UK ITV Westcountry West +1 5 Star BBC Radio Nan Gàidheal Food Network UK +1 ITV Westcountry West HD 5 Star +1 BBC Radio Scotland France 24 English ITV Yorkshire East 5 USA BBC Radio Ulster FreeSports ITV Yorkshire East +1 5 USA +1 BBC Radio Wales Gems TV ITV Yorkshire West ARY World +1 BBC Red Button 1 High Street TV 2 ITV Yorkshire West HD Babestation BBC Two England Home Kerrang! Babestation Blue BBC Two HD Horror Channel UK Kiss TV (UK) Babestation Daytime Xtra BBC Two Northern Ireland Horror Channel UK +1 Magic TV (UK) BBC 1Xtra BBC Two Scotland ITV 2 More 4 UK BBC 6 Music BBC Two Wales ITV 2 +1 More 4 UK +1 BBC Alba BBC World Service UK ITV 3 My 5 BBC Asian Network Box Hits ITV 3 +1 PBS America BBC Four (19-04) Box Upfront ITV 4 Pop BBC Four (19-04) HD CBBC (07-21) ITV 4 +1 Pop +1 BBC News CBBC (07-21) HD ITV Anglia East Pop Max BBC News HD CBeebies UK (06-19) ITV Anglia East +1 Pop Max +1 BBC One Cambridge CBeebies UK (06-19) HD ITV Anglia East HD Psychic Today BBC One Channel Islands CBS Action UK ITV Anglia West Quest BBC One East East CBS Drama UK ITV Be Quest Red BBC One East Midlands CBS Reality UK ITV Be +1 Really Ireland BBC One East Yorkshire & Lincolnshire CBS Reality UK +1 ITV Border England Really UK BBC One HD Channel 4 London ITV Border England HD S4C BBC One London -

I S P Resident , Board A

. ; -i - ' c l t » ; j » . t 7K l* M t - e d 7 Cents M M I O H A 9-year-old Bergen County child suffered two broken TH* teeth in school doing a small chore for the teacher. Her par ents tried to sue the Board of Education; failing, they sued the teacher. They got nothing. But the idea was implanted I I \ [> » K in the mind of the boy and of his playmates and of too many other children that the thing in this world is to 'sue. sue. E V E R Y W E E K sue." There is too much of the “you can't do this to me” feel *n.l SOI TH W RCKN RKY1IW ing among children. Parents mistahflnplv are too often respon sib le . ^ T f v*» *. « . \..i :v< v , : h I \ M H II l!St. N J . I H IM \KV -'0. 10 .8 The Board Of Education Reorganizes T a x R a t e R i s e s Daniel Check! Is President, To Record High Board A lso N am es Coronato I \ I t i e Y L COMMISSION M EETING | . | w d l # l l i h Hearing M arch 11 - HEARS STORM DEBATE ' l.M idliur-r* I O w a* u n veiled la»t wi*ek l«' I llu* Hoard of (annini*s»ort«*rs. ll fortM-a-t* a lux rale of S‘).21 \ d«*l.»al«* on *n«»w » al ill llie t..w |l*l|||i- L •* l. -

Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two

########## Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two AU 9Gem AU 9Go! AU 9Life AU ABC AU ABC Comedy/ABC Kids NSW AU ABC Me AU ABC News AU ACCTV AU Al Jazeera AU Channel 9 AU Food Network AU Fox Sports 506 HD AU Fox Sports News AU M?ori Television NZ AU NITV AU Nine Adelaide AU Nine Brisbane AU Nine GO Sydney AU Nine Gem Adelaide AU Nine Gem Brisbane AU Nine Gem Melbourne AU Nine Gem Perth AU Nine Gem Sydney AU Nine Go Adelaide AU Nine Go Brisbane AU Nine Go Melbourne AU Nine Go Perth AU Nine Life Adelaide AU Nine Life Brisbane AU Nine Life Melbourne AU Nine Life Perth AU Nine Life Sydney AU Nine Melbourne AU Nine Perth AU Nine Sydney AU One HD AU Pac 12 AU Parliament TV AU Racing.Com AU Redbull TV AU SBS AU SBS Food AU SBS HD AU SBS Viceland AU Seven AU Sky Extreme AU Sky News Extra 1 AU Sky News Extra 2 AU Sky News Extra 3 AU Sky Racing 1 AU Sky Racing 2 AU Sonlife International AU Te Reo AU Ten AU Ten Sports AU Your Money HD AU ########## Crna Gora MNE ########## RTCG 1 MNE RTCG 2 MNE RTCG Sat MNE TV Vijesti MNE Prva TV CG MNE Nova M MNE Pink M MNE Atlas TV MNE Televizija 777 MNE RTS 1 RS RTS 1 (Backup) RS RTS 2 RS RTS 2 (Backup) RS RTS 3 RS RTS 3 (Backup) RS RTS Svet RS RTS Drama RS RTS Muzika RS RTS Trezor RS RTS Zivot RS N1 TV HD Srb RS N1 TV SD Srb RS Nova TV SD RS PRVA Max RS PRVA Plus RS Prva Kick RS Prva RS PRVA World RS FilmBox HD RS Filmbox Extra RS Filmbox Plus RS Film Klub RS Film Klub Extra RS Zadruga Live RS Happy TV RS Happy TV (Backup) RS Pikaboo RS O2.TV RS O2.TV (Backup) RS Studio B RS Nasha TV RS Mag TV RS RTV Vojvodina -

Client-Facing Slide Templates

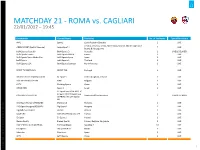

MATCHDAY 21 - ROMA vs. CAGLIARI 22/01/2017 – 19:45 Broadcaster Channel Name Territories No. of Territories Type of Broadcast AMC Sport1 Czech Republic/Slovakia 2 LIVE Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia, Macedonia, Kosovo, Montenegro and ARENA SPORT (Serbia Telecom) Arena Sport 4 7 LIVE Bosnia & Herzegovina beIN Sports Australia BeIN Sports 3 Australia 1 LIVE & DELAYED BeIN Sports France beIN Sports MAX 6 France 1 LIVE BeIN Sports Spain Media Pro beIN Sports Spain Spain 1 LIVE beIN Sports beIN Sports 1 Thailand 1 LIVE BeIN Sports USA BeIN Sports Connect North America 2 LIVE SPORT TV PORTUGAL SPORT.TV3 Portugal 1 LIVE BRITISH TELECOMMUNICATION BT Sport 3 United Kingdom, Ireland 2 LIVE BTV MEDIA GROUP EAD RING Bulgaria 1 LIVE CCTV Molding Sports China 1 LIVE CHARLTON Sport 2 Israel 1 LIVE TC Sport Live 04 DE HD / TC Linear 3 HD / TC Sport Live CINETRADE/TELECLUB Switzerland/Liechtenstein 2 LIVE & DELAYED 03 FR HD / TC 174 Sports HD DIGI Sport Hungary/RCS&RDS DigiSport 2 Romania 1 LIVE DIGI Sport Hungary/RCS&RDS DigiSport 1 Hungary 1 LIVE DigitAlb/SuperSport SS2HD Albania 1 LIVE DIGITURK beIN SPORTS HD 4 & OTT Turkey 1 LIVE Eir Sport Eir Sport 1 Ireland 1 LIVE Eleven Sports Eleven Sports Poland, Belgium, Singapore 3 LIVE FOX SPORTS LATIN AMERICA ESPN Caribbean See Slide 4 54 LIVE GO Sports GO Sports HD1 Malta 1 LIVE Movistar Movistar+ Spain 1 LIVE LETV LeTV Sports China 1 LIVE 2 Copyright ©2016 The Nielsen Company. Confidential proprietary. Nielsen and Confidential The Company. Copyright ©2016 MATCHDAY 21 - ROMA vs. -

Campaign in Ireland: an Analysis

RESEARCH ARTICLE Diageo's 'Stop Out of Control Drinking' Campaign in Ireland: An Analysis Mark Petticrew1*, Niamh Fitzgerald2, Mary Alison Durand1, Cécile Knai1, Martin Davoren3, Ivan Perry3 1 Faculty of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 15-17 Tavistock Place, London, United Kingdom, WC1H 9SH, 2 Institute for Social Marketing, UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies, University of Stirling, Stirling, United Kingdom, FK9 4LA, 3 Department of Epidemiology & Public Health, Western Gateway Building, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland * [email protected] a11111 Abstract Background OPEN ACCESS It has been argued that the alcohol industry uses corporate social responsibility activities to Citation: Petticrew M, Fitzgerald N, Durand MA, Knai influence policy and undermine public health, and that every opportunity should be taken to C, Davoren M, Perry I (2016) Diageo's 'Stop Out of scrutinise such activities. This study analyses a controversial Diageo-funded ‘responsible Control Drinking' Campaign in Ireland: An Analysis. drinking’ campaign (“Stop out of Control Drinking”, or SOOCD) in Ireland. The study aims to PLoS ONE 11(9): e0160379. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0160379 identify how the campaign and its advisory board members frame and define (i) alcohol- related harms, and their causes, and (ii) possible solutions. Editor: Kent E. Vrana, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, UNITED STATES Methods Received: February 5, 2016 Documentary analysis of SOOCD campaign material. This includes newspaper articles Accepted: July 5, 2016 (n = 9), media interviews (n = 11), Facebook posts (n = 92), and Tweets (n = 340) produced Published: September 16, 2016 by the campaign and by board members. -

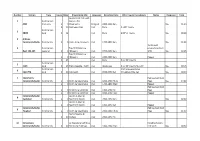

Number Station Type Hours Mins Programme Title Language

Number Station Type Hours Mins Programme title Language Broadcast time Other regular broadcasts Notes Response Total Guaranteed Irish with 1 Commercial, Barbara Nic 4FM multi-city 2 0 Dhonnacha Bilingual 2000-2200 Sun Yes 01:23 0 23 Ceol agus Craic Irish Daily 3 x 90" inserts Commercial, 2 98FM local 0 28 Irish Daily 4'00" of inserts Yes 00:28 3 Athlone Community Radio Community 1 0 Inniu, Inné, Amárach Irish 1730-1830 Sun Yes 01:00 Syndicated 4 Commercial, Top 40 Oifigiúil na programme from Beat 102-103 regional 2 0 hÉireann Irish 0750-0950 Sun SPIN Yes 04:35 Top 40 Oifigiúil na 2 0 hÉireann Irish 2200-0000 Sun Repeat 0 35 Irish Daily 5 x 1'00" inserts Commercial, 5 C103 local 0 15 Blúire Gaeilge - C103 Irish Weekdays 3 x 1'00" inserts Mon-Fri Yes 00:15 Commercial, Irish language jingles 6 Clare FM local 0 30 Cúlchaint Irish 0900-0930 Sat throughout the day Yes 00:30 7 Claremorris Rebroadcast from Community Radio Community 1 0 Scoth na Seachtaine Irish 1600-1700 Thurs RnaL Yes 04:00 1 0 Scoth na Seachtaine Irish 1700-1800 Wed Repeat Rebroadcast from 1 0 Scríobh na nAmhrán Irish 1300-1400 Fri RnaL 1 0 Scríobh na nAmhrán Irish 1600-1700 Tues Repeat Community Radio Anonn is Anall le 8 Castlebar Community 1 0 Mairtín Ó Maicín Irish 2000-2030 Sun Yes 02:00 Anonn is Anall le 1 0 Mairtín Ó Maicín Irish 1000-1030 Sat Repeat Community Radio Rebroadcast from 9 Youghal Community 1 0 Scoth na Seachtaine Irish 2300-0000 Thurs RnaL Yes 01:30 Na Cairteanna le 0 30 Kodexx Irish 2000-2030 Fri 10 Connemara As Gaeilge le Caítríona Broadcast every Community